Uncommon Environments

Using the lens of scientific scrutiny and the emotional possibilities of re-scaling everyday waste for public view, two artists invite a reconsideration of "natural" adaptations in the contemporary world.

The Minnesota Artists Exhibition Program (MAEP) offers a special opportunity for unexpected pairings. Coordinator Chris Atkins and a rotating panel of seven practicing artists find new ways to open the experience of art by selecting those who approach similar themes from separate angles. For the current MAEP exhibition, Trever Nicholas and Ryuta Nakajima lead the viewer through novel designs of both personal and public environments.

An expert in Japanese esoteric Buddhism, a published biologist and an exhibiting artist, Ryuta Nakajima’s work offers a deft synthesis of contrasting fields. As a scientist, Nakajima studies the schooling behavior and color-changing properties of cephalopods like squid and cuttlefish. Nakajima, the artist, recreates camouflage effects by fabricating in his work the same neurological process which allow chameleons and frogs to react to their surroundings through expressions of pigmented cells called chromatophores. For his MAEP exhibition Umwelt (a German word for ‘environment’) Nakajima experiments with both the cephalopods and his audience.

Advancing a recent study to provoke dynamic chromatophoric responses, Nakima placed cuttlefish atop copies from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts’ collection and documented the animals’ unsuccessful yet spectacular attempts to blend in. To further manipulate and amplify the effects of our own environment, Nakajima has decorated dozens of resin cephalopod molds with iconography ranging from depictions of the constellation Gemini, suprematism, andUltraman.

As Atkins writes in an essay accompanying the exhibition, Nakajima “likens his resin copies, formally and conceptually, to the hyper-collectible figures” of Japanese sofubi toy designs which have grown in popularity through mass marketing and fashionable “blind boxes.” Nakajima enhances this sense of collectibility by elevating three molds onto their own encased pedestals. Sitting atop plush pillows and covered with gold leaf, platinum, or thousands of Swarovski crystals, these cuttlefish respond to an umwelt of decadent kitsch. Here the audience again becomes part of the implied environment to which these false cuttlefish adapt. Standing alone or with a group of visitors, the separate reflections of cuttlefish stitch together a kaleidoscopic display of our common differences. Urging us to recognize our own identity in these creations, Nakajima’s variations on a theme offer a moment to consider the ways we have chosen to accept the convenient waste and excess of modern industry.

Just a few steps away in the next gallery, Trever Nicholas also challenges us to consider the daily debris of urban living. In choosing to value overlooked and discarded materials – detergent caps, cotton balls, zip ties – Nicholas invites the viewer both to reflect on that detritus and to refresh our understanding of resourcefulness. His Plug Rug first appears as a glorified doormat. Move closer, and the viewer sees thousands of rubber ear plugs, a mere fraction of the the total number of such cheap remnants generated by industrial inefficiencies. By patiently handweaving each plug into the nylon fishing net, Nicholas has created a Sisyphean meditation on the sweeping waste of contemporary manufacturing practices.

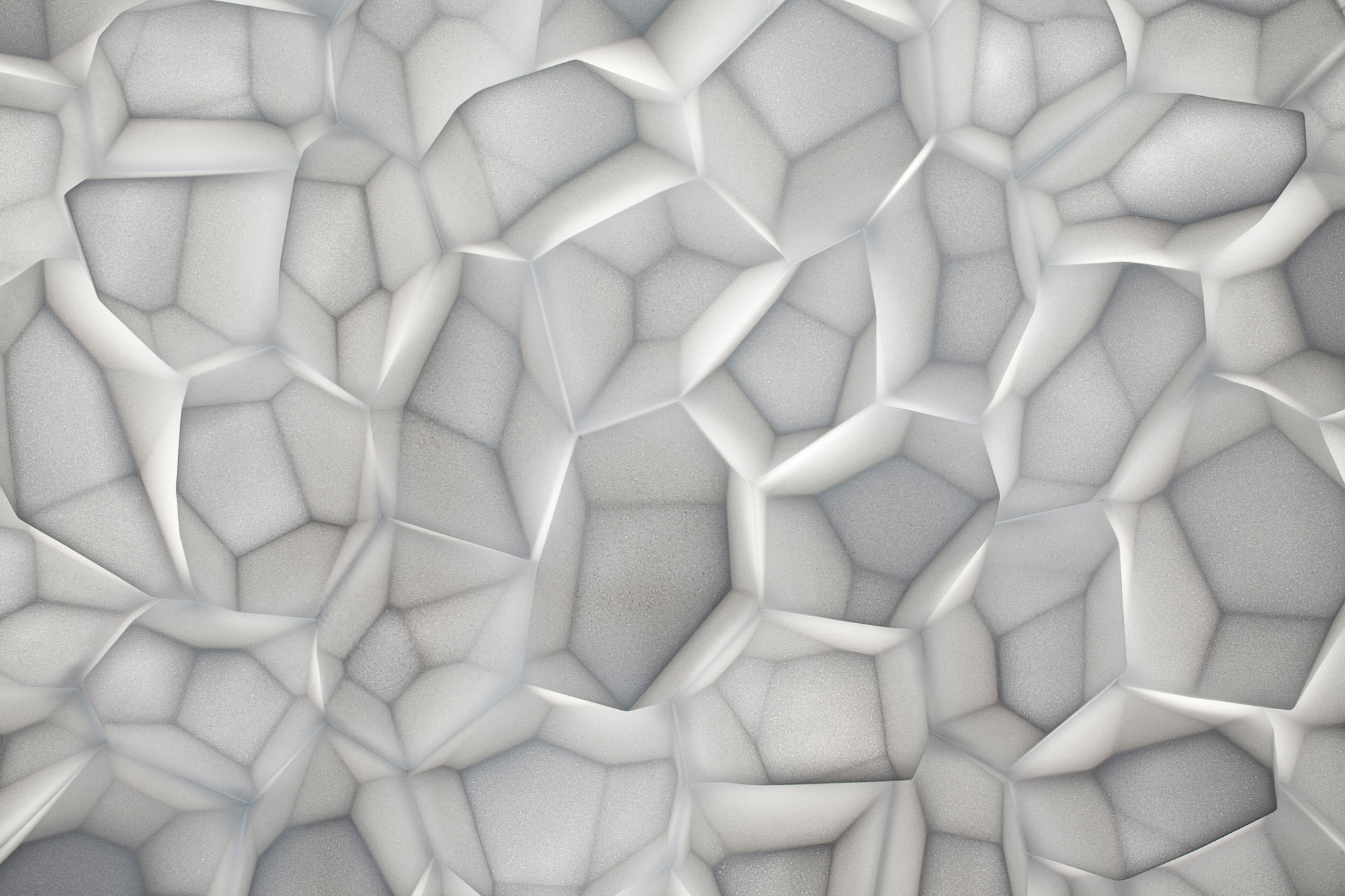

For the MIA, Nichols used a CNC router to carve 14 blocks of styrofoam into a massive, backlit installation. By enlarging the scale of a rendering of the molecular structure of salt, to fit the entire wall, Nichols’ Luma (Voronoi Cellscape) in effect places the viewer under the microscope. Though voronoi diagrams were designed to convey coherent sets of macrodata in applications as far reaching as theoretical mathematics, city planning, and epidemiology, Nicholas offers no such interpretive key. His is a map of nothing in particular. Atkins calls it a “view from nowhere.” Stand just close enough, and Luma will consume your field of view – suddenly you’ve lost yourself in its breadth. Turn around, and you may just see the same wondering look in the eyes of your fellow gallery visitors.

We’ve all collected toys and rocks and things. We’ve all tossed wrappers aside, or salt over the shoulder for good luck. We’ve all contemplated our reflections in a mirror. With the objective scrutiny of scientific observation and the emotional swell of impossible magnification, Nakajima’s Umwelts and Nicholas’s Luma (Voronoi Cellscape) together allow the viewer an uncommon vantage point on those shared experiences, and new ways to consider how we adapt to our own environments.

___________________________

Related exhibition information:

The Ryuta Nakajima and Trever Nicholas exhibitions, Umwelt and Luma, are on view in the MAEP galleries of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts through September 29. There is an artist talk scheduled for September 19, 7 pm. For more information: http://www.artsmia.org/index.php?section_id=67

___________________________

About the author: Nathan Young recently graduated from Macalester College and will attend the University of Chicago to study the intersections of art and economics. He owns one work of art. Find him on Twitter: @nrp_y