Grief, Play, and Gleaning at the End of Empire: On Used

Interweaving the work of Rachel Breen, Heather M. Cole, and Shana Kaplow with Agnès Varda: possibility beyond disposability

Across the threshold to the show Used, featuring works by Shana Kaplow, Rachel Breen, and Heather M. Cole, I imagine these words: “There’s nothing new under the sun.”

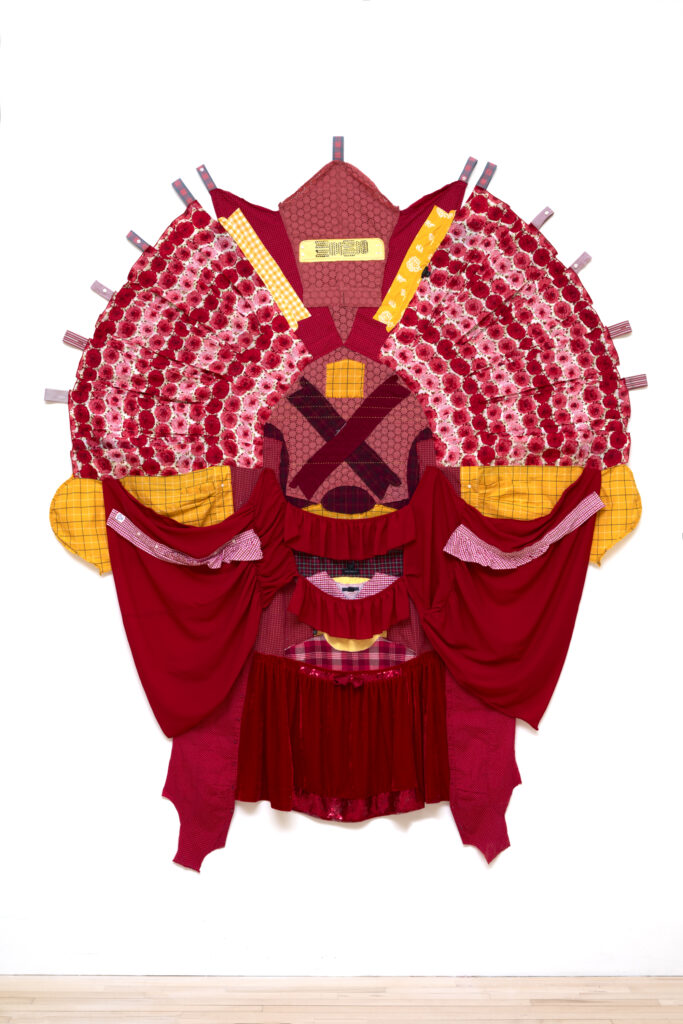

This show that challenges the myth of newness, disposability, and progress is installed in the Inez Greenberg Gallery at Artistry in Bloomington, Minnesota. Used comprises sculptural works and paintings assembled from predominantly reclaimed materials. Heather M. Cole’s work uses molded plastic packaging materials; Rachel Breen re-animates second-hand skirts, button-down tops, vests, and other sartorial and domestic textiles; and Shana Kaplow brings old and new materials together in meditations on energy consumption, power, and grief.

Together, their works seek to “speak to how we use materials and how they also ‘use’ us.” I want to zoom in on this formulation as a portal to other ways of thinking, and how this feedback loop complicates notions of linear progression and opens to other possibilities.

A loop a hoop a way through a way about. I see Agnès Varda’s self-filmed hand capturing tractor trailers (the conveyors of our material dependencies) on the highway in The Gleaners and I.

“I like to capture them,” she says.1

Capturing, collecting, gleaning, and transmuting the material evidence of our consumer culture is a creative act, and, at the end of empire, an optimistic one, too.

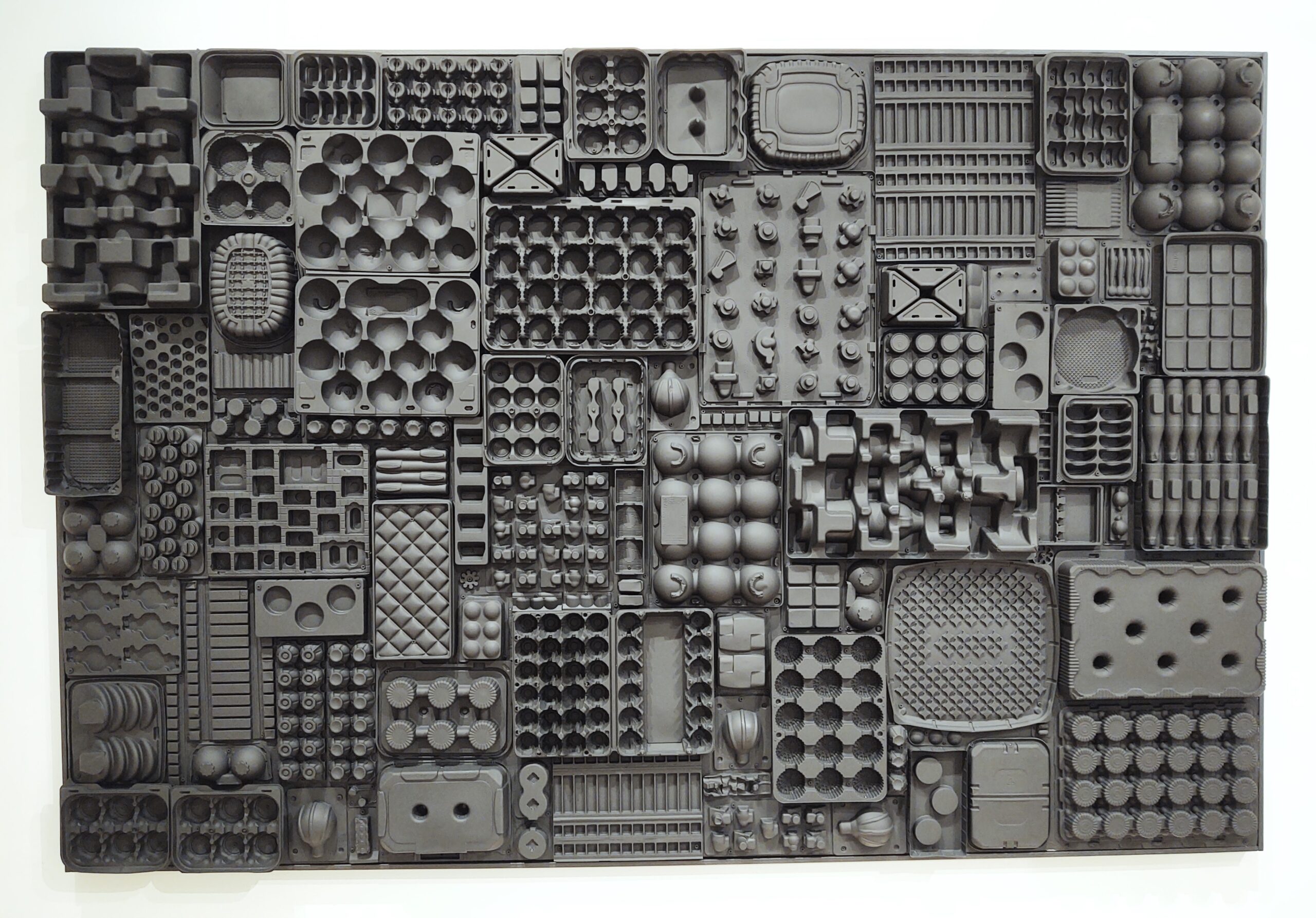

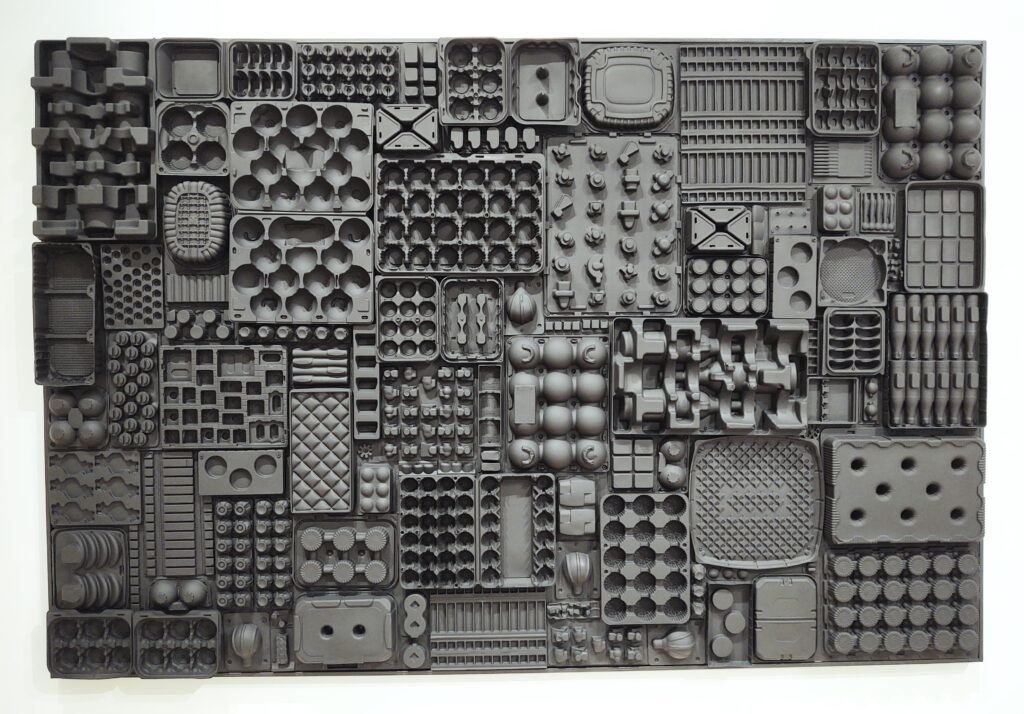

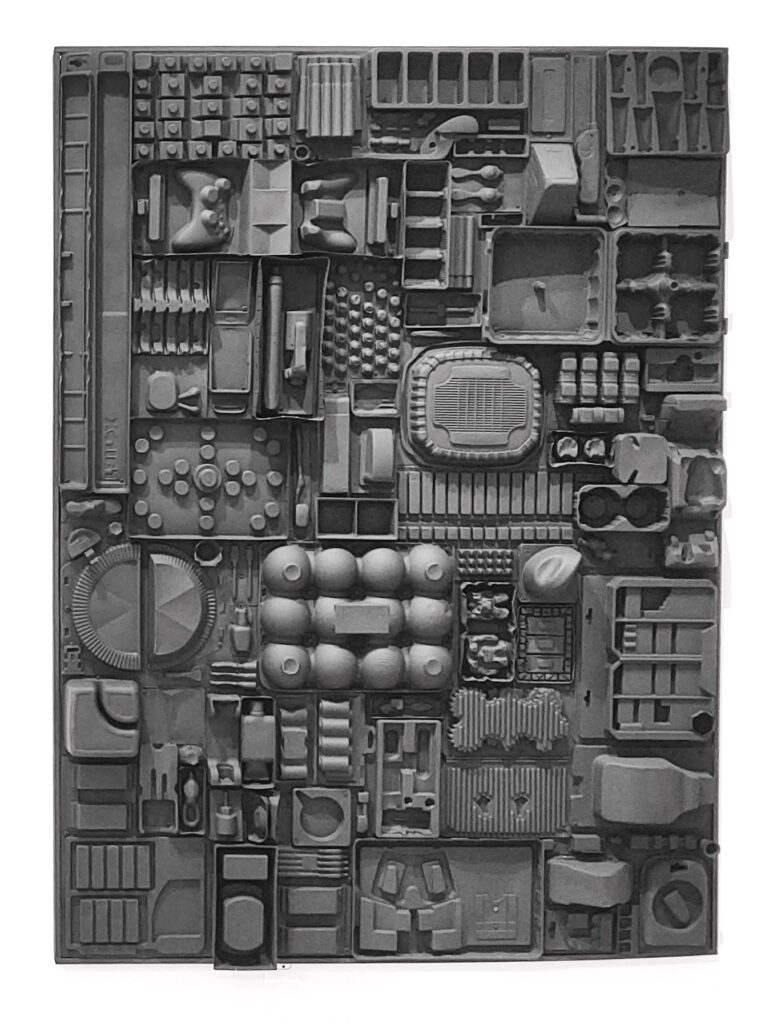

Take, for example, the works of Heather M. Cole featured in the show, which include wall-mounted, monochromatic (black), framed assemblages of molded packaging materials that come together in topographical conglomerations defamiliarized from their original intent.

Framed, we see how plastic packaging waste, not unlike a urinal in a gallery, “can be intriguing and even beautiful . . . .”

Likewise, such materials are “Frequently . . . more interesting and costly than the object it originally contained . . .”2

If you find this hard to see, give a toddler a toy in its packaging–what’s more interesting to this fresh-to-the-world being? The grotesque, overwrought item of purported amusement or the box, the packaging?

In Heather’s assemblages, the contours are nuanced and sometimes mysterious in their specificity, even sensuous, as in the curves and swoops, constrictions and inflations of Noir, lightbulb reliefs evocative of baubles, tops, palaces, ornaments, cupcakes, bombshells, and grenades.

In other works, such as Cathedral we are confronted with a practically esoteric assortment of shapes and surfaces, topologies.

There’s an oblique curiosity in the making that redirects my impulse to conclude “Death Star dashboard” but it’s still there hovering in the air, along with Heather’s striking Stufficated–a near floor to ceiling circular curtain of clear plastic packaging. Holodeck or hollow-feeling-glut-of-stuff-deck.

I notice not all of the pieces of plastic are pristine, in some cases you can see traces of the cardboard they were affixed to. This observation is followed by an impulse–that feels very much in keeping with the logic of a compartmentalized, containerized world–to value purity. A suffocating thought. In the “stufficated” sculpture in my mind, a little fascist has joined me.

What thoughts such a gigantic plastic jellyfish-like presence capable of asphyxiation accommodates! Should it be a surprise a plastic monolith revealed to me my own plastic programming?

Heather says she wants the work to inspire different thinking, including considering “the materials used, who is doing it [the thinking and the making and the thinking-making], where you are seeing it, …[and] who gets to decide what is art.”3

As such, Heather’s works, via plastic valances gleaned from this world, lifts the plastic veil between this world and another possibility.

“To glean,” explains Varda, in The Gleaners and I, “is to gather [originally wheat] after the harvest.” The documentary begins in the G section of the dictionary: “A gleaner is one who gleans. / In times past, only women gleaned. / Millet’s ‘Glaneuses’ were in all dictionaries.”

“I’m happy,” says Varda, “to drop the ears of wheat and pick up the camera” in this film, that in its own listening and gleaning, accommodates chance, (sometimes heartbreaking) inquiry, and more.

I return to Varda’s wizened hand with the trucks on the highway.

“I like to capture them,” she says, “To retain things passing? No, just to play.”

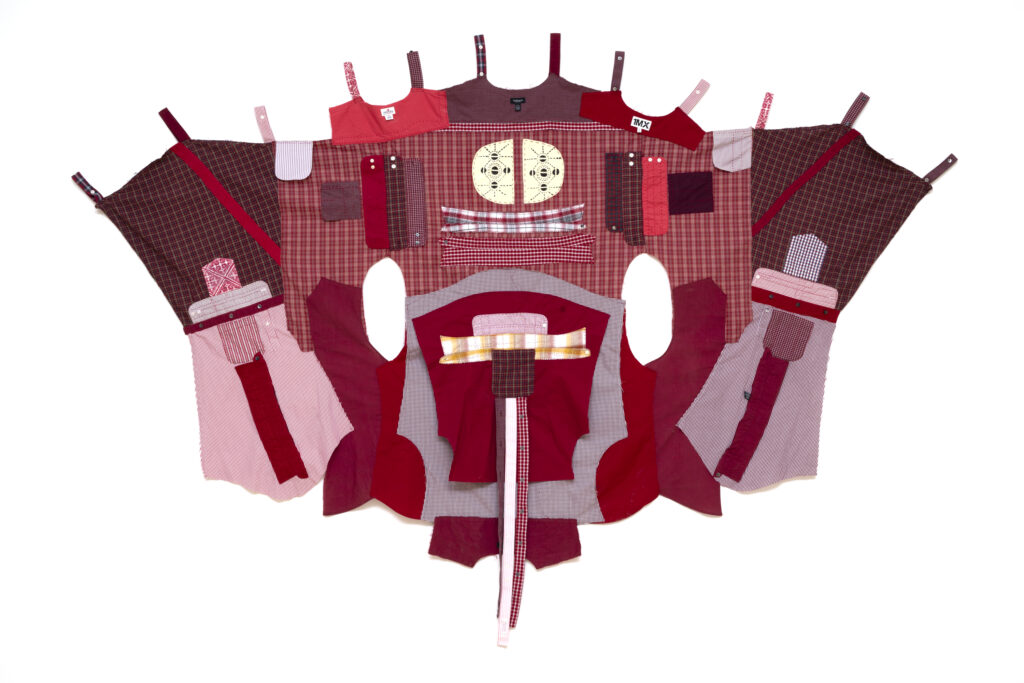

This gleaning spirit of play shines in the works of Rachel Breen featured in Used.

Large-scale, warm-hued banners clearly made of used clothing fragments festoon the middle zone of the show..

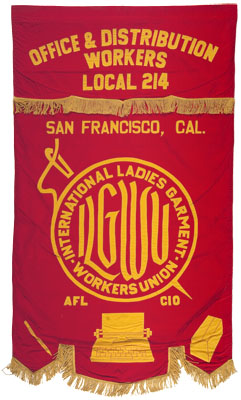

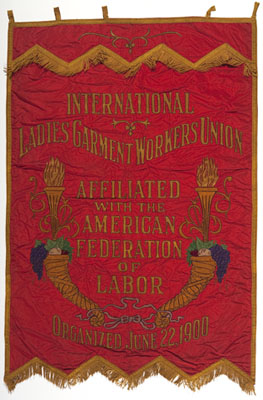

Inspired by the reds and golds of the protest banners carried at Labor Day marches, strikes, and protests by the International Ladies Garment Workers Union in the early 20th century, Rachel’s Banners for the Commons bring a sense of pageantry to the project of re-making our world.

And how do we do that? From the inside-out, seems to be the suggestion of Used, with all that is already available and otherwise exiled from view.

Like ceremonial masks for monolithic faces, the anthropomorphic banners bring to this viewer’s mind Rammellzee’s Garbage Gods, and his Ikonoclastic thinking that in order to overturn a reality, you have to liberate the symbols of that reality from their imprisonment by that reality. For Rammellzee, inspired by the subversive lettering practices of medieval monks, the symbols were letters, and the trash he liberated/transmuted into garbage gods for his cosmic space opera.

For Rachel, the symbol is the status symbol of clothing that she has gleaned second-hand: “I have taken used clothes apart and then ‘re-made’ them as a metaphor for what’s needed to re-think and re-make the global garment industry and really all capitalist systems that treat workers and/or environment unjustly.”4 The means of liberation, in contrast to Rammellzee, is pageantry, jubilation of the non-martial sort. That said, one might still be tempted to see the banners as warrior masks.

Many intricacies of the original labor invested in the garments are still intact–cuffs, button-down collars, hems, pockets, button holes. Rachel: “It is particularly important to me that the clothing parts I work with REMAIN clothing parts.”5 This decision brings tenderness and a built-in honoring of the labor that came before in this labor.

It’s the spirit of the commons. “…the commons as an antidote to capitalism,” Rachel writes, “when we think about the commons we are asking–how do we share and protect resources with each other, with future generations, and with all non-human life on earth? The banners signal this–that we must rethink, reimagine, and embrace new systems that are based on values that are different from the economic system we have inherited.”6

The works in Used also illuminate the under-recognized commons that are already available to us, and are presented in a common space–a public gallery in a community center that is free and open to the public.

In the patchwork essay “The Ecstasy of Influence,” composed of writing lifted from others, Jonathan Lethem (and Michael Newton) writes, “The world of art and culture is a vast commons, one that is salted through with zones of utter commerce yet remains gloriously immune to any overall commodification. The closest resemblance is to the commons of a language: altered by every contributor, expanded by even the most passive user. That a language is a commons doesn’t mean that the community owns it; rather it belongs between people, possessed by no one, not even by society as a whole.”7

This between is the site of relation, of magic, of flux, and transmutation. The title for Agnès Varda’s documentary in French is Les Glaneurs et La Glaneuse, which translates literally as “The Gleaners and The Female Gleaner” (who we know to be Varda), but The Gleaners and I loses subtlety with the I, such a heavy word in an individualistic culture that the emphasis falls there, when the emphasis and the cinematic magic occurs in the “et” the “and”–the realm of relationality.

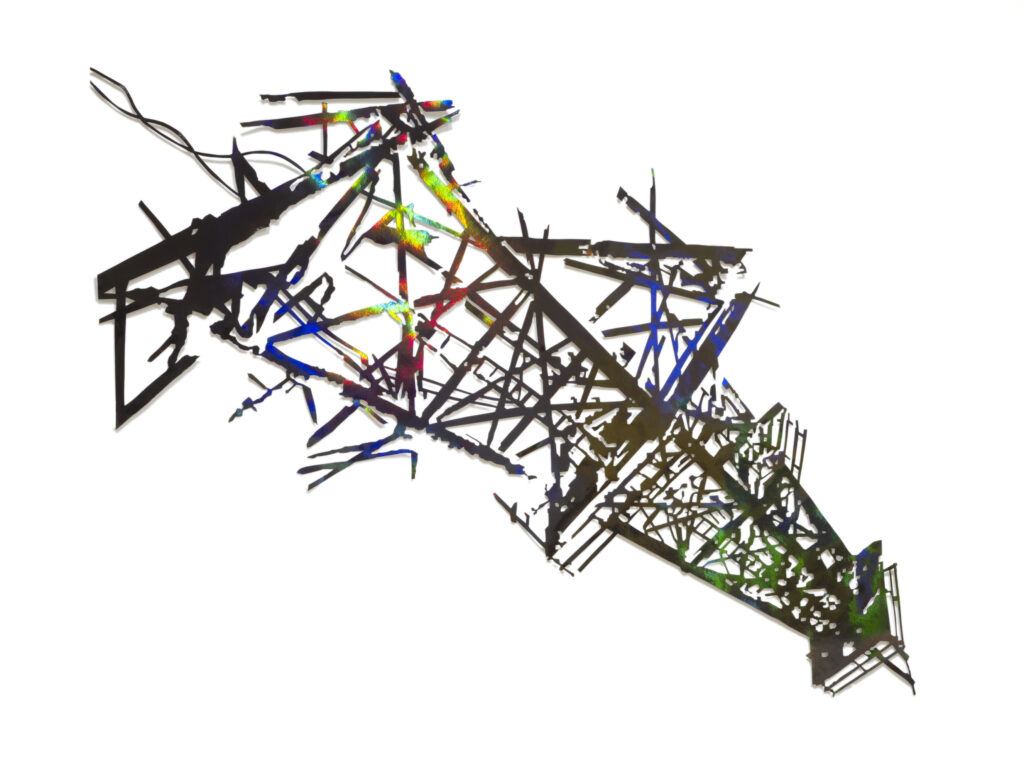

A nuanced meditation on relationality is what Shana Kaplow’s works in Used invite.

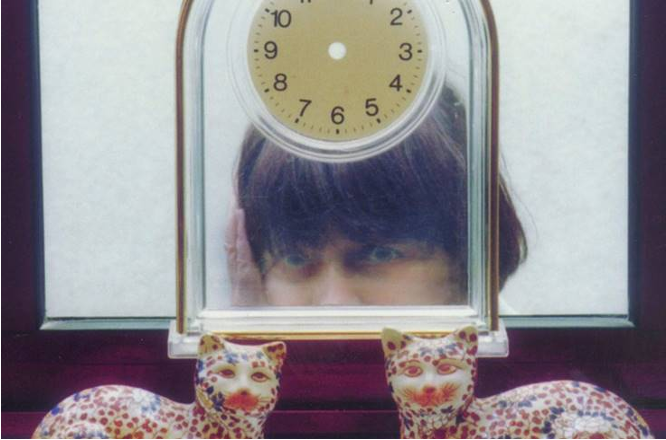

My attention is particularly captured by Apparatus for Grieving, a blown glass parabolic mirror that paradoxically tracks the sun in a windowless gallery, evoking the loneliness of satellites and the devotion of sunflowers whose faces follow their benefactor throughout the course of a day.

You might remind me, as I write this, of the first stanza of William Blake’s “Ah! Sunflower”:

Ah Sun-flower! weary of time,

Who countest the steps of the Sun:

Seeking after that sweet golden clime

Where the travellers journey is done.8

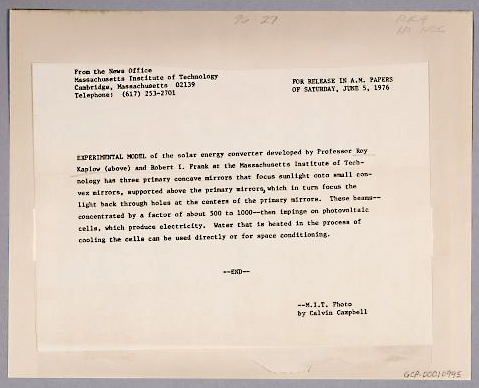

Kaplow’s work is inspired by her father’s solar energy project (1976-1980), which he was working on before he died suddenly at the age of 49.

Shana: “I remember when my father died, my entire sense of time changed, what mattered changed. I was rearranged and reoriented. Earth is traveling at 67,000 miles per hour through space and spinning on its axis at 1000 miles per hour, yet we barely notice.”9

Those who linger over the apparatus will notice the mirror’s slow movement in correspondence to the sun’s path, sometimes known as the day arc.

The apparatus is animated, animate, maybe even animus (son of the sun?) in a different sense of time-keeping. “I imagine the sculpture as if it were a figure, receptive to our human projections.”10 I pause here to appreciate that in this idea, the mirror/receiver, tuned to the sun, is inside collecting our light emissions (projections are energy too, no matter how fictional or brilliant or programmed), as if we are all stars.

The apparatus, “is both hapless and hopeful.” writes Shana in our correspondence. It tracks the sun without “seeing” the sun. We can hear in this a metaphor for grief (in which that which we were oriented to has disappeared) and a means of wayfinding in the dark, hope.

Later, Shana writes: “The apparatus also feels to me like a listener or a searcher.”

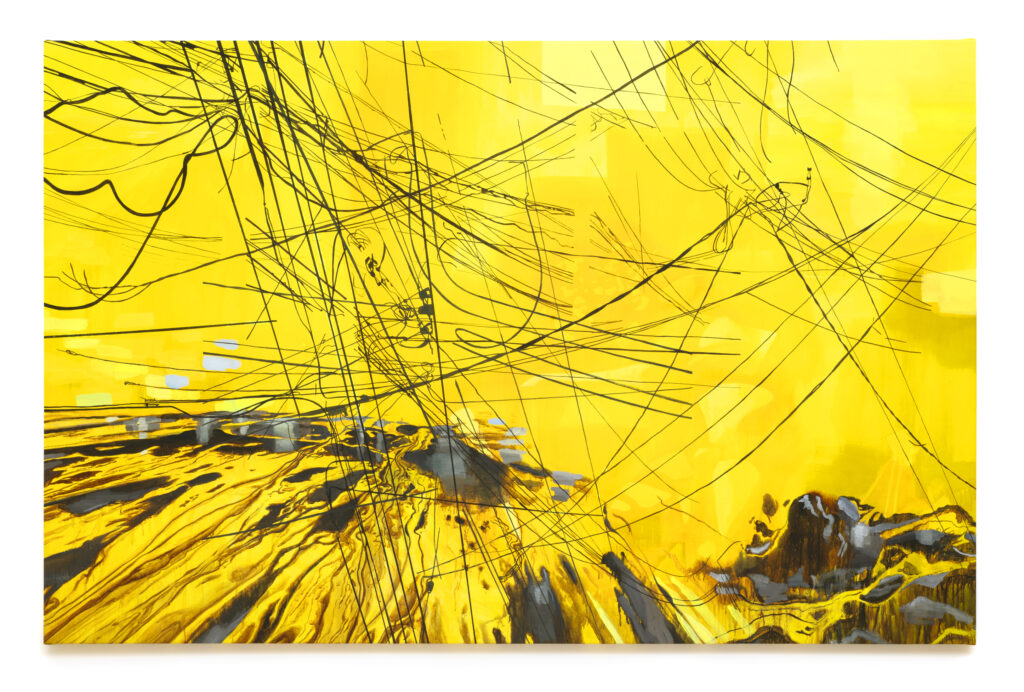

In the absence of the sun’s presence, the space glows with Shana’s luminous painting Available Light, in which ostensibly severed power lines (time to cut the cord) swim in a sea of radiant solar yellow.

This painting and the other images, like poems, are distillations, these orbiting a central figure of loss and alterity.

After the death of Shana’s father, “Ronald Reagan’s presidency (1981) ushered in the most rapid acceleration of global warming and continued reliance on fossil fuels….Looking back over the last 40+ years, I see my loss and grief have coincided with the collective loss of environmental stability and the continued political power of the fossil fuel industry. The feeling of lost opportunity, both personally and collectively, is overwhelming.”11

Apparatus for Grieving thus becomes “a stand-in for my own and our collective grieving process, because moving through the grief is also a way toward being able to think about (and possibly find hope in) a way forward.”

Used brings me to the thought that our particular American way of repressing history in favor of a grand myth of democracy is a way of banishing that which we do not want to confront, and we continue to act this out at the very level of our material mediated life, building into that which we consume that which we also banish/trash (see Fox News, MSNBC, etc.).

It is the planned obsolescence of the linear, the flat line. We’re flat-lining. Meanwhile, on another path: “The sun rises and the sun sets, and hurries back to where it rises.”12

“I have not been interested in the modernist concept of progression, the avant garde notion of advancing in time,” artist Jack Whitten once said, “My position is more of a cosmologist,”13 making explicitly clear: a transmutation of time is in order.

Back to our threshold: “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.”

No new thing might be an old way to talk about art, but I want to think about it less as an aesthetic conclusion and more in the spirit of Whitten, of a worldview that challenges notions of advancement/disposability, single-use perception/concept, and banishment.

There’s grief present in this show and simultaneous play–in adulthood, you can’t have one without the other?

In this tension, a defamiliarizing strangeness takes hold.

Used, in its collection of transmutations, quietly invites us to see things less as things and more alive, as processes (acts of relationality). Per the artists these processes include:

- “Imagining what the supplier was trying to protect so fiercely” (HMC)

- “Imagining a better solution” (HMC)

- “Playing, re-thinking, re-imagining, re-conceptualizing, re-contextualizing, re-arranging” (RB)

- “Not knowing . . . trusting the materials, the meaning they hold, permitting them to lead me” (RB)

- “Tuning into the somatic sensations of the substances and structures that produce energy” (SK)

- “Nudging materials toward the transitions between states of matter” (SK)

An artist in The Gleaners and I says of his gleaned materials: “What’s good about these objects is they have a past, they’ve already had a life, and they’re still very much alive. All you have to do is give them a second chance.”

The generosity and curiosity at work in these acts of relating to the material at-hand welcome correlatives in other realms of daily life–education, civics, other arts, science, engineering, healthcare, humanities, technology, economics.

It requires not banishing the things we make, our bodies, our ugly feelings and thoughts, each other, and opening ourselves to less familiar ways of knowing and listening receptive to the unseen and other forms of perception–e.g. intuition.

When asked what she thinks her film offers people today, Agnès Varda replied, “I would say energy. I would say love for filming, intuition. I mean, a woman working with her intuition….. It’s like a stream of feelings, intuition, and joy of discovering things. Finding beauty where it’s maybe not. Seeing.”14

Seeing through/beyond prescribed programming. Seeing energy. Intuiting as a form of energetic gnosis. One can feel this at work in the works of Used. Per William Blake: “The eye altering alters all.”15 Thus the show’s ultimate invitation is one of perceptual mutation, an invitation to shift, to (re-)see another world that is also this one.

Used is on view at Artistry March 22, 2024–May 12, 2024. → More information