Art, Water, and Reciprocity

A conversation between Duluth-area artists Karen Savage Blue, Moira Villiard, Ashley Hise, and Michaela Rai on the sacredness of Lake Superior

Lake Superior is an immense and vitally important body of water. For many of us who are fortunate to live near the big lake, our lives and creativity are deeply informed by this vast being. At a time when the lake faces numerous threats from human activity, art helps us connect with the sacredness of the water.

This conversation explores four Duluth-area artists’ intimacy with the water: Karen Savage Blue, Anishinaabe visual artist; Moira Villiard, visual artist and designer, Fond du Lac Ojibwe direct descendant; Ashley Hise, Duluth potter, sculptor, and teacher; and Michaela Rai, embodiment and documentary photographer. We discuss their art and creative practice in relation to the water, both as a source of healing and as a living entity to care for in reciprocity.

EMILY LEVANGLet’s talk about your personal connection with the water.

Karen Savage BlueOn Brighton Beach there are big boulders in the water. Every year, as early as possible, I jump off into the water. The earliest part of the year that I ever jumped in that water was in April. Now, that’s really cold. Sometimes when you come up, you’re gasping for breath because it’s so cold.

Michaela RaiI’m going to get really emotional talking about this, but the lake has held me in my worst times. The lake saved me in some ways. In times when I was feeling very unsafe in my life, those were times when I was really drawn to the lake. Being in the lake requires you to be so present. You can’t be anywhere but in your body, because it’s so cold and it’s so fresh. There’s movement, and you have to breathe. I’ve been jumping in the lake for 18 consecutive months.

KSBReally? Oh my gosh. I’m really glad that I can relate to another person like this.

MRAshley, you jump in when it’s cold too, don’t you?

Ashley HiseYep. And I’m always trying to convince people to go with me. My heart is full, with the waves dripping off, even if it’s freezing cold, as long as there’s just a little bit of sun.

Michaela Rai, Breath #2, 2022.

Michaela Rai, Converge, 2022.

Michaela Rai, Dappled, 2022.

Michaela Rai, Grace Beneath, 2022.

Michaela Rai, Mellow, 2022.

Michaela Rai, Edges #1, 2022.

Moira VilliardWhen I think of water stories, I think of a period of time when I was at an early peak in my artistic career, about to burst out onto the scene. I ended up losing the ability to use my dominant arm for two or three years. I had to completely reorganize my life structure. During that time I would walk down to Fond Du Lac Creek on the Reservation, which was really close to my house. In the springtime, when the water would finally break, I would just go shove my entire arm into the creek.

That was the only time in that period of chronic pain where I actually felt any kind of relief—complete rushing cold, frozen water hitting my arm. So it was a very healing memory of the creek. And just laying there, in the middle of the woods, letting my arm dangle in the water.

KSBMoira, that would make an awesome painting.

ELHow is your creative practice informed by your relationship with the water?

MVI get asked to do a lot of art about water. It’s a recurring theme. And I feel like you can never have enough artwork about water. With my first experience doing a mural in Duluth, it was all about the significance of water in the region. I had asked people what’s missing in the public art in Duluth, and literally everybody said water, which I thought was really interesting.

MRTo try to encompass the lake is such an enormous task. I was very intimidated by it for a long time.

I’ve always had a documentary focus to try to show things exactly as they are. I started with people, and saw that the camera is like an instant judgment. People automatically feel observed and they start moving their body differently. They start breathing differently. I noticed this, and my process has been developed to tell the truth exactly as it is, and to create an environment where people can show up exactly how they are.

A whole person is not something you can capture in a photograph. So I just shifted that perspective to the water—how do we show how it moves, the oxygen in the water, the rocks, the way the water moves over the rocks? I’m slowly seeing as I dive deeper into this project of working with the water, how it’s the same thing as with people, just shifting and trying to capture the different elements that make up the essence and the spirit of the water.

AHSomething in your work, Michaela, that I find so fascinating is how you capture the relationship between light and water. It’s just one of the most ethereal things, and you do it so beautifully.

MRThank you. I think that’s also part of a focus I’ve always had, whether it was people or now the water—life is hard, and there’s so much beauty and there’s so much pain, and it’s just how it is. We don’t get away from it. And I never wanted to show bodies or people’s experiences as just one positive happy thing, because that’s just not the truth, you know? And so the same with the water, to see the darkness and the light at the same time has been really beautiful and very metaphorical.

Ashley Hise, Symbiosis, 2023.

Wild clay on the south shore of Lake Superior. Photo: Pointed North Photography.

Ashley Hise, Basalt, 2023.

Ashley Hise, Lunar Water, 2023.

Ashley Hise, Mineral Fluid, 2023.

Wild clay on the south shore of Lake Superior. Photo: Pointed North Photography.

Ashley Hise, 5th Wave, 2021.

AHI’ll jump off of that too because, literally, I’ve been digging clay out of the lake, and it’s really gritty and dark. The forms that are emerging out of that clay and that dark, gritty clay body are really different than what I’ve done for a long time.

What I’ve done for a long time is more spiritually connected to water, and involves me walking along the shore, finding shells, bones, fossils, and admiring the growth patterns in those, and then connecting those patterns to the fluidity of water. That’s how I do a lot of the surface designs on my work.

But now digging this clay, literally using this clay out of the lake, out of the shoreline and having these rougher, rockier forms, it feels like they’ve been missing each other. They needed each other, and they have that symbiosis of the two. When you said that—there is the light in the dark, and the pain and the joy—I appreciate you acknowledging that. I feel like good art does that, it makes you feel not alone in that.

KSBI’ll tell you a story about the water. Twenty years ago I was going through this really depressive time in my life where I got my divorce, had to move away from my family and kids, just isolated all by myself, living with my brother in the upstairs room of a cabin, really pitiful. I’d sit on the floor and I’d paint. Along the door I would take some canned water, and line it all up along the bottom. That’s how I kept it cold, because there was a nice draft coming through because my dad built the house. He wasn’t too concerned about weatherization. I was working on this really sad painting for who knows how many weeks, just feeling awful about everything.

I just finished, and I put it on the wall next to the door where all my water was. All of a sudden there was this burst. It was one of those cans of water bursting open because it froze.

It sprayed onto my painting. I was in shock.

But I was doing a mantra at the time: “Don’t do anything when you’re upset. Don’t ever do anything when you’re angry.” In other words, just don’t react. Take your time. So I remember picking up that painting and thinking, “Oh my God, I gotta fix this. There’s water on it.” But then I thought, “No, I can’t do anything when I’m angry. I’m gonna just leave it alone and deal with it in the morning.”

I wake up in the morning and I look at it, and by that time it had dried. I thought, “This is awesome. It’s rain.” I received this gift, of these raindrops so wonderfully strategically placed on this painting. I title it The Weeping Sky.

Karen Savage Blue, Bruce Savage, Knocking Rice, 2021.

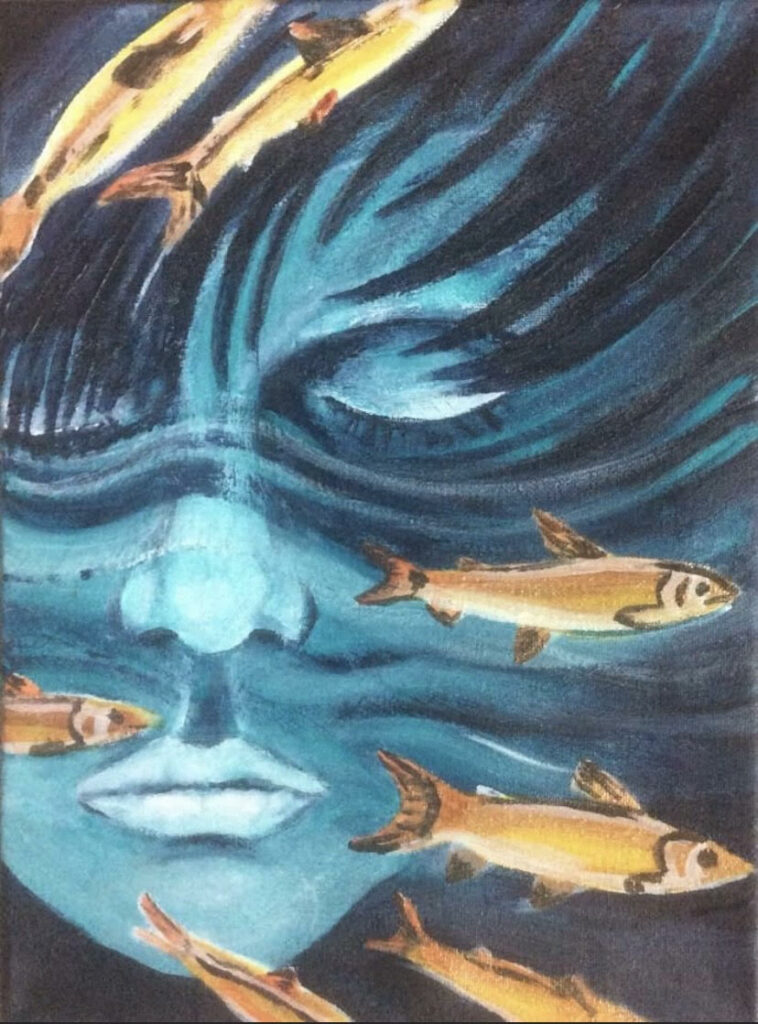

Karen Savage Blue, Deep Blue, 2022.

Karen Savage Blue, Down in Deep Waters, 2022.

ELAre there specific water issues you are most concerned about?

MVI do a lot of artwork around wild rice. Wild rice is this interesting sort of being. When you eat it, every rez lake has a different taste to the wild rice, reflective of that ecosystem. It creates a unique personality profile for each of the bodies of water. It makes me think of how the threats of mining and pollution impact that.

Fun fact, I’m a foodie, like a hardcore foodie. And I feel like every time I try and talk about serious things, I get really into food for some reason. But I think of the magic of flavors that are not replicable and, how if you wreck these bodies of water, those are flavors that you can’t necessarily recreate or even bring back.

I have a piece called The Waters of Tomorrow, which was influenced by one of the teachings that Roxanne DeLille gave, recognizing that the water today is the same water that our ancestors have ingested, used, taken care of, been around, all of those things. That teaching is a great metaphor for our actions on this planet. And besides being a metaphor, water is also a physical connector of generations, and what we have is literally what we need to leave for people and future generations.

It really makes me think about the consequences of all our actions. And is there a way we can leave better conditions, better water for future generations, or are we just going to be on this path of continuously desecrating it?

MRThe culture that I was raised in was very resistant to considering environmental issues. So the further I get away from that, and the more I return to my own connectedness with who I actually am as a person, and with nature and with the water, the more I get to educate myself and learn. It sounds like several of us have spent time in the desert, and it puts it in such perspective of how precious our water really is. Sometimes it’s overwhelming to look at the enormity of the problems, but to just look at our own area of stewardship and in our own way, we are all pointing people back to the sacredness of it. I find a little bit of hope in that, that by showing people the truth of the preciousness of what we get to be in the presence of, I hope that that inspires more sacredness and more reflection in tiny ripples. No pun intended.

Moira Villiard, The Waters of Tomorrow, 2019.

Moira Villiard, Chief Buffalo Memorial, 2022. Collaborative community-painted walls, mermaid wall by Sylvia Houle and Awanigiizhik Bruce, Ojibwe pictograph by Moira Villiard.

Moira Villiard, UMD Collaborative Turtle Mural.

Moira Villiard, Duluth Climate March collaborative mural, 2019.

Moira Villiard, Where the Food Grows on Water, 2018.

Moira Villiard, Chief Buffalo Memorial, 2022. Canoe by Sylvia Houle, community wall.

AHI was also looking at your work, Moira, with the Chief Buffalo Memorial project and thinking of the idea of prioritizing clean water above all else. It seems far off in some ways, like—why can’t we just make this happen? Moira, you bring that piece, and Indigenous nations are doing that and have been doing that for so long. If we could somehow get it together and prioritize our clean water… For me mining and extraction are the issues that I think about a lot.

ELAshley, I’m seeing your way of harvesting clay as an antidote to the forcefulness of extreme extraction. You have a very reciprocal, conscious relationship with harvesting clay from the Earth. Could you talk about your process?

AHI think of harvesting as a reminder of how sacred our materials are, and how unique the things that we create out of our surroundings can be. This is something certainly that I try to communicate through what I make, but then also when I work with kids. How do we use what’s around us responsibly and treat it well? Rather than try to profit off of it or take too much, not treating it like it goes on forever. And put yourself as the steward of the land, in relationship with the land versus owning it, extracting it, selling it.

KSBThis area in front of my house, it’s not good for swimming. It has piles of mud and cattails and reeds and things like that. And my neighbors, they have a nice dock and an awesome swimming area for their kids, which is cool and all that. And at one point I thought, “Hey, I want that. I want a nice little shore.” And I could have done that. But then I thought, “You know what, maybe it’s not just about me. You know, I have these loons and these geese that I’m responsible for.”

I really protect those loons. Sometimes people will come by in a kayak to look at them, and I will go out there and stand with my arms crossed. There’s so few places on this lake for a nesting loon. I decided I’m not gonna “fix” this area so that I can walk out there and swim. I’ll just leave it as a safe place for these birds to come. And they do come.

So I think there are some things that people can do, as far as preserving our water and our habitat. Each and every one of us can do something.