Shoreham Repository: A Feralegium

A gathering of excerpts, or a botanical reading practice, in conversation with Gudrun Lock's Shoreham Repository and the edges of a truck and trainyard complex in Northeast Minneapolis

Florilegium comes from the Latin flor (flower) + legere (gather), cousin to the Greek anthology—anthos (flower) + logia (a collection). Before the florilegium as a form came to be a botanical compendium (circa 1590), it was, in medieval times, a sacred reading practice in which monks gathered textual flowers, i.e. excerpts (some called them “sparklets”) from Christian, classical, and pagan writings to explore resonances between the ostensibly disparate in a “middle age,” an historical in-between. Today I’m gathering weeds, for a feralegium, as I am in my middle ages in another in-between time, thinking about an in-between place, known as the buffers of Shoreham Yards, and the artist who showed them to me, Gudrun Lock.

Between modernity and the unknown.

Between civilization and its viscera.

These are not parallel tracks though many converge here.

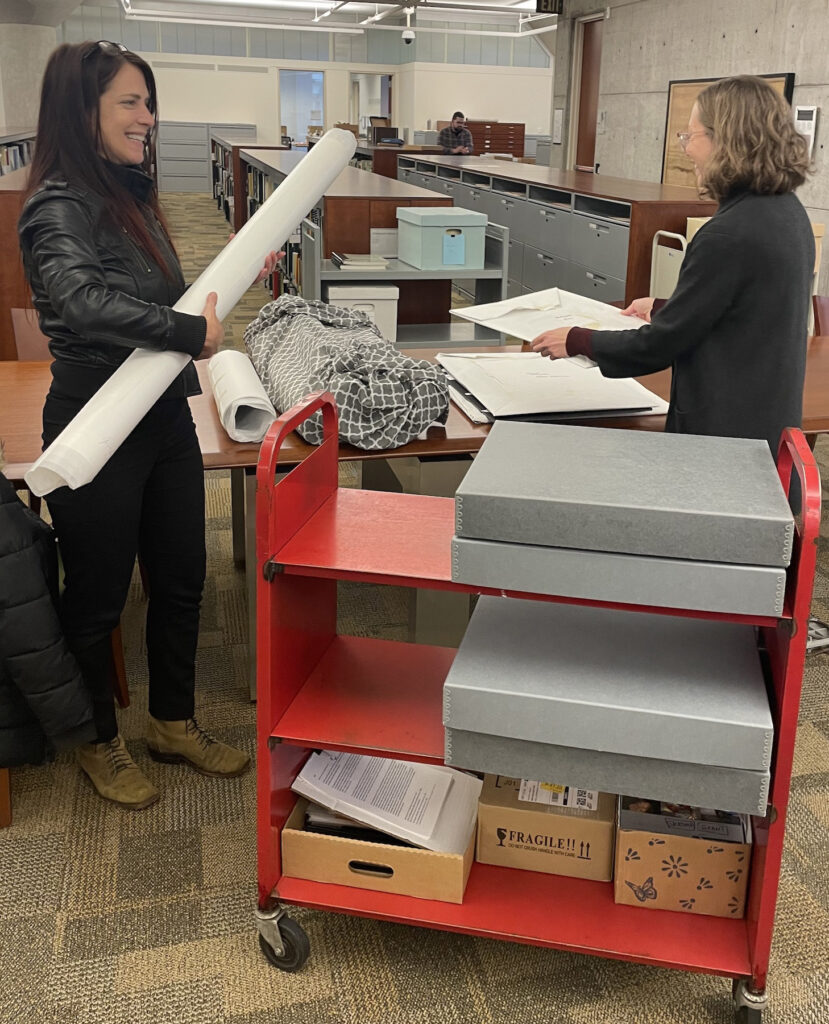

In Gudrun Lock’s introduction to the Shoreham Repository—a new archive she compiled and curated that’s entered the Special Collections in the Minneapolis Central Library—she writes,

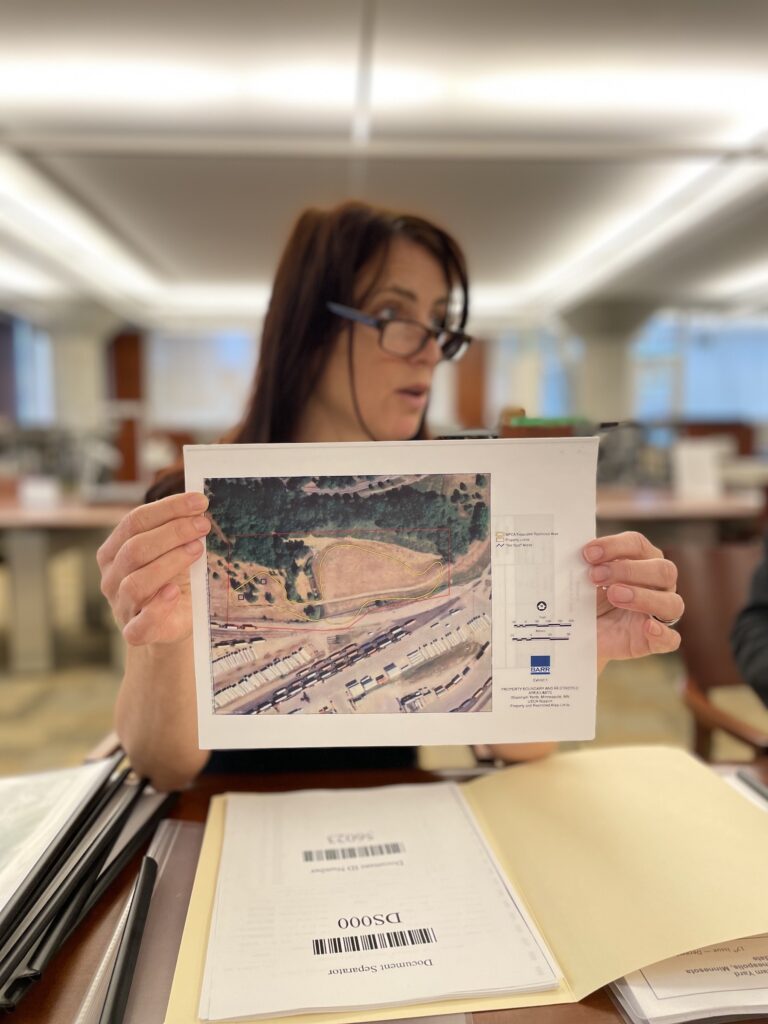

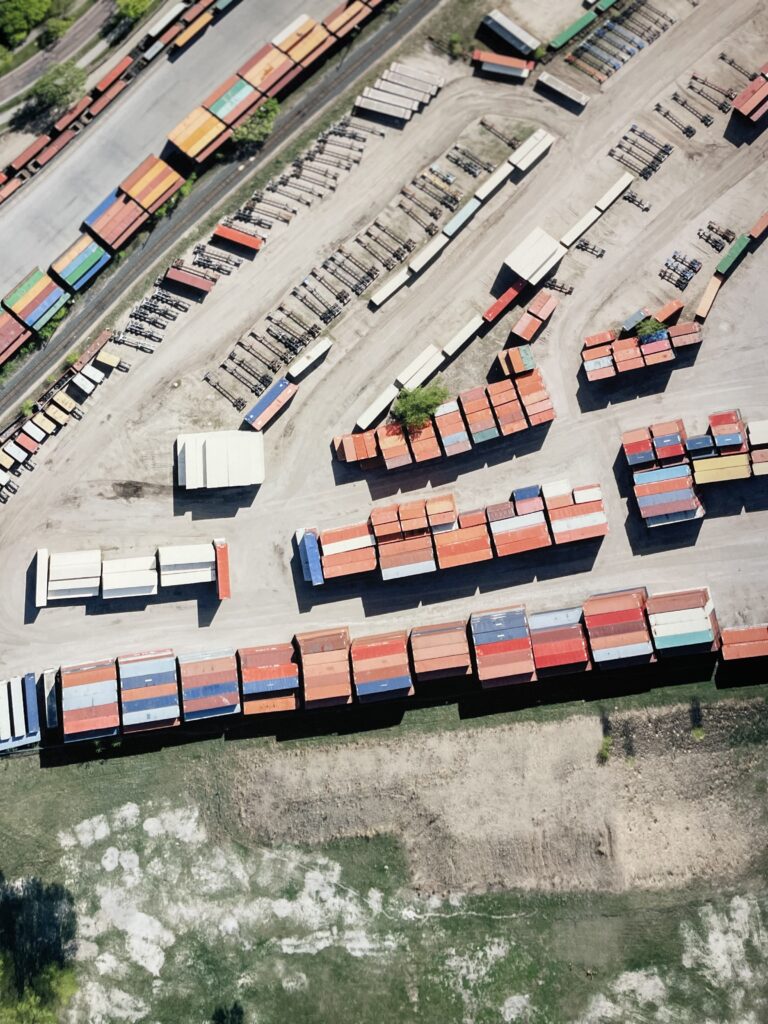

In 2019 I turned my attention to an interstitial world two blocks from my house in Northeast Minneapolis, the buffers of an active intermodal train and truck facility called Shoreham Yards. Owned by Canadian Pacific Kansas City railway, Shoreham contains four Superfund sites and is surrounded on all sides by patchy grass, shrubs and trees that act as buffers between it and the neighborhood. On daily dog walks along these marginal landscapes I began imagining how they might serve as sites of transformation.

This massive, often unnoticed, industrial convergence across 230 acres lies within Minneapolis, a city vexed by systematized repression. Minneapolis, a canary in the imploding mine of nation-thoughts, when the collapse of the I-35W Bridge over the Mississippi revealed the country’s crumbling infrastructure, and the murder of George Floyd revealed again the country’s rotten ontological infrastructure, the subsequent uprising (re)awakening (how many times do we have to awaken) the world to the toxic systems of power we understand as order. When empires fall, it’s the ruptures that demand our attention. Sometimes they are cataclysmic and sometimes they are as small as a new thought.

It was the work of scientist Diana Beresford-Kroeger, and the film Call of the Forest, that connected Gudrun to an older/other way of knowing:

I remembered who I was when I was seven years old…like a lot of young people, I knew that I could communicate with trees and rocks and water. It seemed so obvious to me. But our culture basically told me to shut up and to stop thinking that way, because it was childish or fantastical or ridiculous….[T]he film gave me a kind of permission to start thinking that way again…Seeing [trees] as beings with their own needs, seeing them as communicative and relational.

The next morning when I walked my dog along Shoreham, I had the thought: a forest should be here.

Gudrun Lock, in Kathryn Savage’s Ground Glass, Shoreham Repository/SR

Relationality and imagination (seeing the unseen) light the in-between.

One boundary opens another.

Two very different tools.

Archive Key, SR

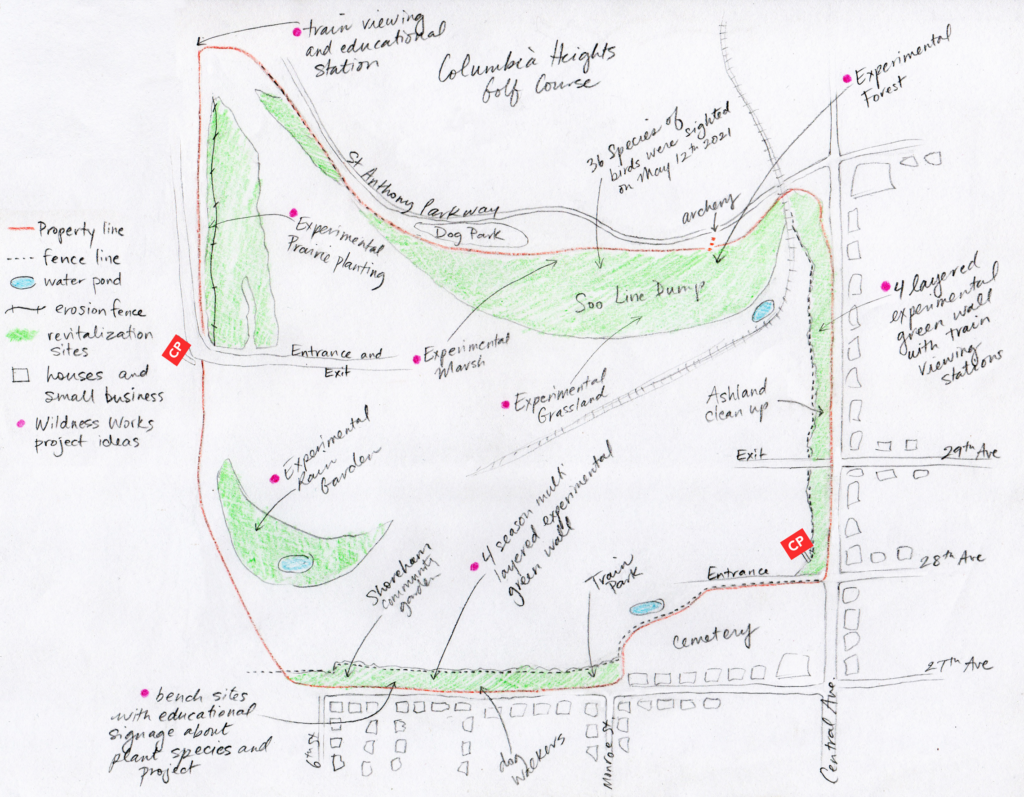

Three illustrated maps (8.5”x11”) with observational notes taken while walking around the buffers of Shoreham Yards in 2019, drawn by Gudrun Lock. The third map imagines the possibility of the buffers as sites of revitalization; this map Gudrun used as a graphic tool in discussion with Canadian Pacific Railway about the possibility of legal access to the buffers to add plant and tree diversity.

Archive Key, SR

I’m afraid of cities, writes Sartre, but you mustn’t leave them. If you go too far you come up against the vegetation belt… It is waiting. Once the city is dead, the vegetation will cover it, will climb over the stones, grip them, search them, make them burst with its long black pincers; it will blind the holes and let its green paws hang over everything.

Jean-Paul Sartre, Nausea

Perhaps some wormwood for this nausea, Sartre.

A staple in the herbal apothecary, this astringent herb is a must-have for settling a turbulent upset stomach.

Lisa M. Rose, Midwest Medicinal Plants

Artemisia Absinthium, a type of wormwood used to make absinthe and a native of North Africa, is naturalized throughout much of the United States in highly disturbed sites such as highways edges, construction zones, and the perimeter of Shoreham Yards.

Shoreham Yards Fact Sheet, SR

Absinthe can excite sexuality, stimulate ideas and conversation, or dissolve the brain.

Dale Pendell, Pharmakopoeia

Compost mentis? We have become so top-heavy.

In an interspecies call and response we don’t often hear, the so-called weeds that burst through the concrete and populate the liminal spaces of our cities often correspond medicinally to that which ails us. A lush stand of mullein—which reduces acute inflammation and relieves lung congestion (Midwest Medicinal Plants)—grows alongside tracks feeding into Shoreham Yards, as if the plant knows the pain in the laying of the line, the congestion caused by the train’s exhaust. We are, after all this time, it seems, exhausted.

The Artemisias or Wormwoods are a distinctive clan belonging to the Aster or Composite family. They are generally very bitter, harsh tasting plants with a gray fur on the leaves, which usually look gray, silver, or dark green.…They are nature’s promise that out of devastation life will spring anew.

Matthew Wood, The Book of Herbal Wisdom

I’m in the weeds with a writing project, I told a friend today. “In the weeds”—a phrase I learned the hard way when working in restaurants—I propose be reassigned to describe getting lost in the unknown, the terror and delights of the wild entanglements of writing, and more, quite specifically the strange pull of the feral propensities of the buffers of Shoreham Yards.

This pull to the possible the wild thought / this remarkable persistence in an era of doom / this pull to not knowing / to play is what Gudrun has tuned into in the buffers. And in her own expression of this energy, she has drawn in a motley array—anthropologists, engineers, arborists, artists, sound designers, statisticians, naturalists, ornithologists, politicians, biologists, historians, corporate PR, landscape architects, musicians, poets, et al.

She’s the one at recess out in the brush, the one stooped down in intense focus who then stands up, waving her arms, “You guys! Over here! A portal!”

Artemisia vulgaris, aka mugwort, also grows in the buffers of Shoreham Yards. Known in some circles as the teacher of all the plants, and in the Middle Ages as the “mother of herbs.” The one who protects.

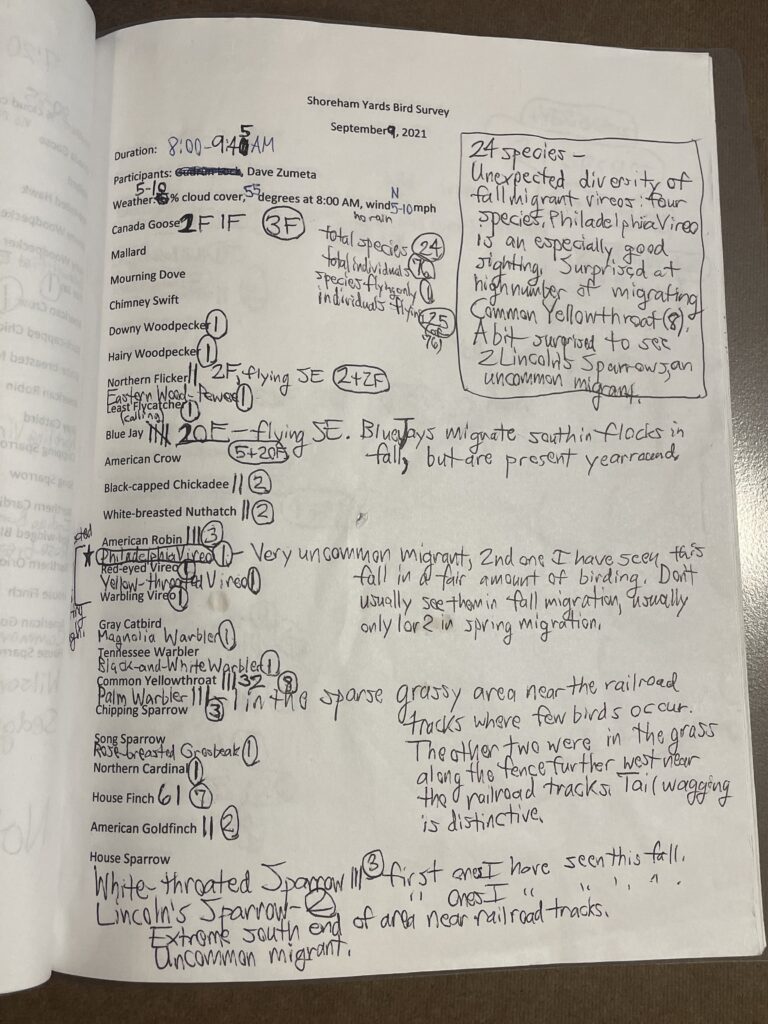

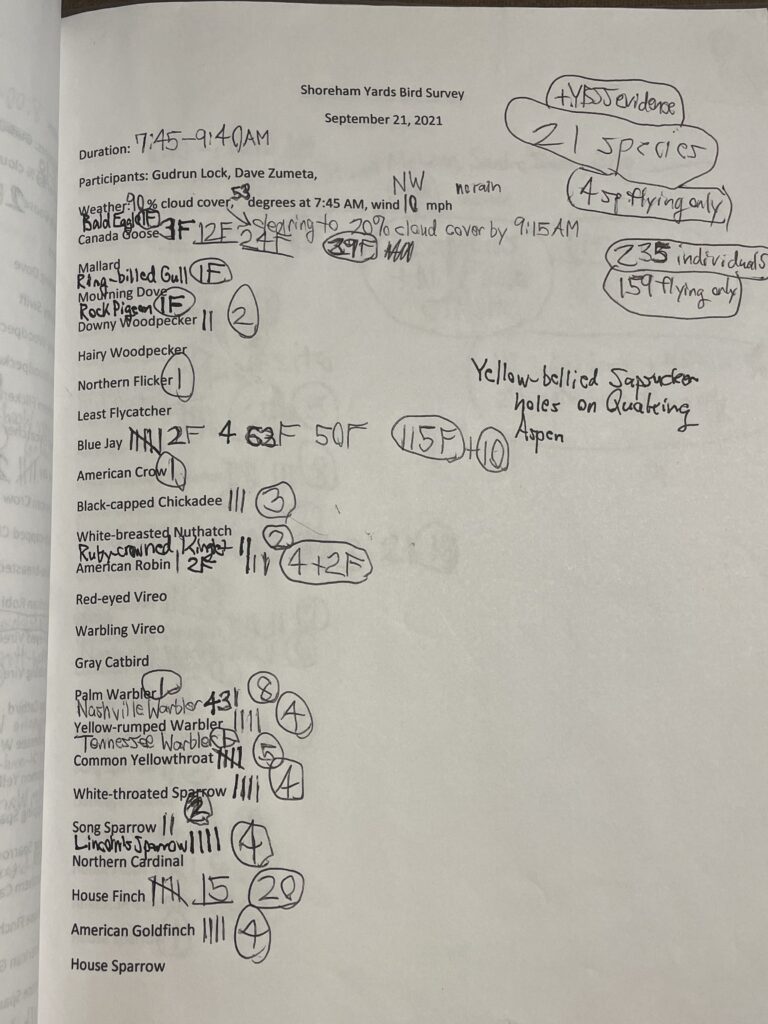

The Shoreham Repository includes photographic portraits by Jeffrey Skemp of trees in the buffers; handwritten birding notes by Dave Zumeta; archival photos of workers at Shoreham Yards, alongside photographic portraits of workers today by Leslie Grant; inventories of plants, insects, and fauna seen at Shoreham Yards; a print by Jenny Schmid; a painting and collage by Janet Lobberecht; four large archival boxes with artifactual and nature-made gleanings; a photographic collection of portals, i.e. mushrooms and animal holes; and so much more.

Four pairs of underpants…were buried three inches deep for two months around the perimeter of Shoreham Yards as part of a soil vitality experiment. Friends, researchers, and other artists volunteered to first bury, then dig up these items as a playful way to begin a conversation about brownfield sites and living soil. The underpants help visualize the activity of living bacteria and fungi in soil that might otherwise be thought of as potentially contaminated or dead. Number 18 was buried near the roots of a crabapple tree and subsequently turned purple.

Archive Key, SR

There were many other pairs, some 80 total, of geocached tighty whities resurrected from their burial sites. My daughters and I were part of this expedition. “We’re going to what?” “We’re going to dig up underwear with Gudrun.” What was most surprising was how readily devoured they were, in soil conditions presumed less conducive to the fecund work of decomposition. These memento mori, both punny (perhaps our real dirty laundry is our relationship with inevitable decay) and in that pun—a quiet, soiled humiliation.

Don’t care how rich you are / Don’t care what you worth

Memphis Slim, “Mother Earth”

Humiliation: see humble.

Humble: from Latin humilis, “lowly, humble,” literally “on the ground,” from humus, “earth”

Meanwhile: I imagine a miles-long caravan of train cars full of secret, privately owned art going nowhere rumbling in the distance.

The art world is the only unregulated market that’s also legal. It’s a great place to hide money. It’s a great place to pretend you’re somebody without having any particular gifts, which means that for people with talent, it’s disheartening a lot of the time…

David Velasco

Gudrun, trained as a visual artist/sculptor, is now, in her work with Shoreham Yards, a kind of liminal world-walker, negotiator, revelator. She is gathering, gleaning, stoking, tending social energies where many worlds cohabitate and cross-contaminate, seep, invade, co-emit. There’s an ongoingness to this work about neighborhood, capital, humans+morethanhuman relations, frustrations, imaginations. This is work in the pluriverse, the place of many worlds at once. Many funders and review panels seem not to get it. And specialists of a certain kind bristle territorial in the face of such firemaking (if attention is energy is heat/light).

In “Beyond Face,” artist Claire Pentecost looks to define a paradigm of the artist in which the artist serves as conduit between specialized knowledge fields and other members of the public sphere by assuming a role we call the Public Amateur.

Not that we need to categorize, but I like the suggestion of amateur, if only because amateur has its roots in love (i.e. the Latin amare—to love).

As such, the artist becomes a person who consents to learn in public….to question something in the province of another discipline, acquire knowledge through unofficial means, and assume the authority to offer interpretations of that knowledge, especially in regard to decisions that affect our lives. The point is not to replace specialists, but to enhance specialized knowledge with considerations that specialties are not designed to accommodate.

“Beyond Face”

Precedents and corollaries: the poetics of Agnes Varda’s The Gleaners and I; the transformative vision of artist-in-residence at New York City’s Department of Sanitation, Merle Laderman Ukeles, who turned a landfill into a public park; Mark Dion’s ideas of collecting, cataloging, performance of science, how his work plays the game in a way that exposes its limitations and its beauty; the “midden pit” that anthropologists sift thru to make sense of lost civilizations, making sense of people by what they left behind (notes from a conversation with Gudrun); the ingenuity of killdeer birds; and the fierce maternity and perspicacity of the artemisias.

We have entered, in a very old sense, the territory of Artemis.

Artemis-Diana, once the wild mother of vegetation, was the goddess of the “out there.” This “lioness of women“ was tamed by Indo-Europeans in an entirely different manner. She was rendered chaste and frigid, she was made into a virgin.

Hans Peter Duerr, Dreamtime

Out there Artemis, not the exiled virgin. Past edginess into the flux and uncontrollable otherwhere. Goddess of the hunt of fecundity and fertility of green volition. There is an Artemisian fierceness, even martial strategy, to Gudrun’s work. She has what a planetarily inclined friend described as “Mars vibes.” There’s precision, perseverance, and cunning. Google “Gudrun meaning” and you get “battle.” Dig deeper and you find “rune” or “secret lore.” It’s true, I think she might be an undiscovered chapter in Temporary Autonomous Zone. She brings immense care to the work. And she has a gift of drawing people in, inspiring others to creation.There’s something perceptual in her perseverance that brings to mind Diane di Prima’s “Revolutionary Letter #75 / Rant”:

You cannot write a single line w/out a cosmology a cosmogony laid out, before all eyes there is no part of yourself you can separate out saying, this is memory, this is sensation this is the work I care about, this is how I make a living

It seems too late to compartmentalize anymore. All of those train freight containers stacked like legos.

Goods that move through Shoreham Yards: forest products, merchandise, steel, plastics, pulp and paper, liquids (regulated and non-regulated), grain products, perishable products (beverages, confectionary, dairy, fresh and frozen meat and produce, frozen foods, sea food, and pharmaceuticals).

Shoreham Yard Fact Sheet, SR

Meanwhile: The last glacier [on the continent] retreated 30,000 years ago.

Shoreham Yards Fact Sheet, SR

In 1956, Lloyd Stouffer, the editor of the U.S. magazine Modern Packaging, addressed attendees at the Society of the Plastics Industry meeting in New York City: “The future of plastics is in the trash can . . . . It [is] time for the plastics industry to stop thinking about ‘reuse’ packages and concentrate on single use. For the package that is used once and thrown away, like a tin can or a paper carton, represents not a one-shot market for a few thousand units, but an everyday recurring market measured by the billions of units.”

Max Liboiron, Pollution is Colonialism, SR

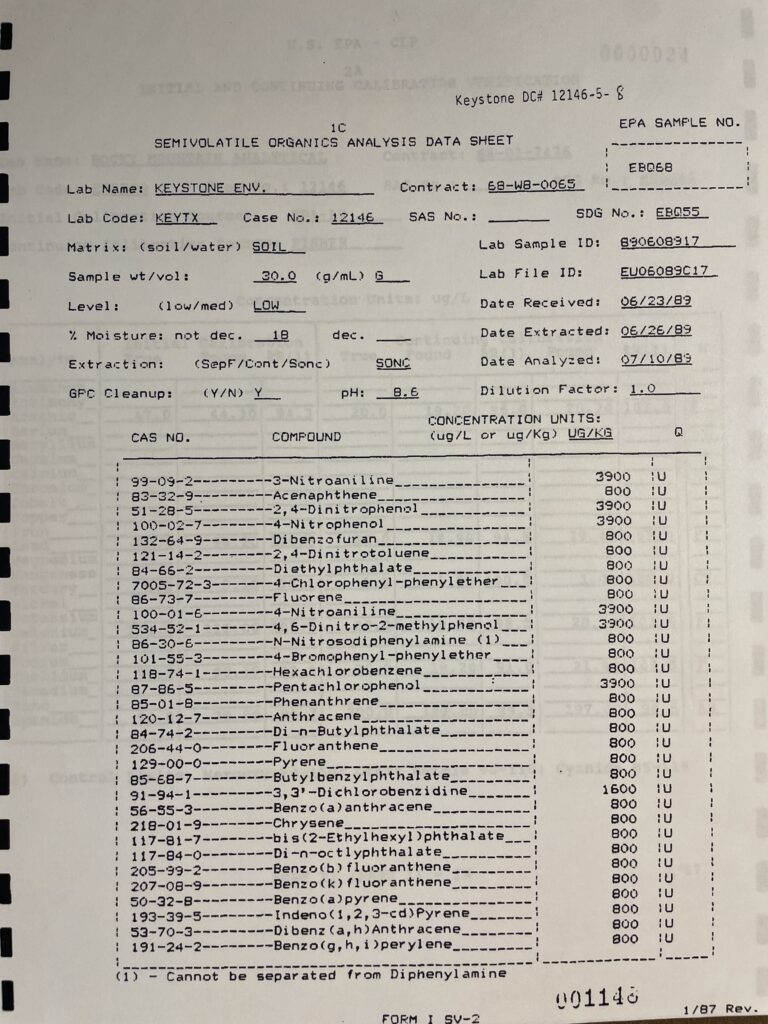

The archive’s name, Shoreham Repository, is also that of Canadian Pacific Kansas City’s own online repository, which houses communications and data related to pollution mitigation efforts going back to 1988. The legal-ese and supposed objectivity of that official collection functions as a facade of transparency. The goal of this archive, on the other hand, is to proliferate perspectives and potentialities while highlighting shadows and gaps.

Gudrun Lock, SR

We are living off expired or expiring stories.

Vanessa Machado de Oliveira, Hospicing Modernity, SR

Box #1: South side buffer, 27th Ave NE from Monroe St to 6th St NE

Found on site:

- Book cover, Getting the Most Out of Life, An Anthology from Reader’s Digest, 1946

- Grains of wheat fallen from train cars

- Taconite pellets fallen from train cars

- Empty bottle of vodka

- Remains of a sunflower

Lest there be no more telling of stories at all, some of us out here in the wild oats, amid the alien corn, think we’d better start telling another one, which maybe people can go on with when the old one’s finished. Maybe.

Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction”

The Shoreham Repository brings us closer to understanding that what’s at-hand, this in-between time we are in, that this multivalent crisis is essentially a crisis of perception (Fritjof Capra, The Turning Point). And, that in the buffers, there is a portal to portals, to the ontological otherwise.

At a time in history when all our former certainties about how the world is or should be or will be are gradually (or not so gradually) abandoning us, now is the time to come to terms with flexibility and uncertainty, to learn to dance with life, experiment, wait and see, be patient, do things differently. Here then is a precious opportunity that is almost always overlooked

Anni Kelsey, The Garden of Equal Delights, SR

Wátakiŋyaŋ k'a ȟemáni k'a iyéchiŋkopte kiŋ hená hóthaŋka. Planes and trains and cars, they are loud Tkha thaté kiŋ isám hóthaŋka, But the wind is louder Wakíŋyaŋ hothúŋpi kiŋ sam hóthaŋka, The thunder is louder Nihówaste kiŋ owás sam hóthaŋka, Your good voices are louder

Liz Cates, Wakáŋyaŋkéwíŋ, SR