The Art of Play

Art historian Sheila Dickinson reviews Andy DuCett's sprawling funhouse of an exhibition, "Why We Do This," on view at the Soap Factory through November 11.

Andy DuCett’s Why We Do This is a must-see, must-experience exhibition. I could describe it to you in great detail, but like all good art, secondhand reporting just doesn’t do the work justice. Not to mention, the unexpected twists in DuCett’s sprawling show are too good to spoil by revealing them here — part of the pleasure of the show is in discovering them for yourself.

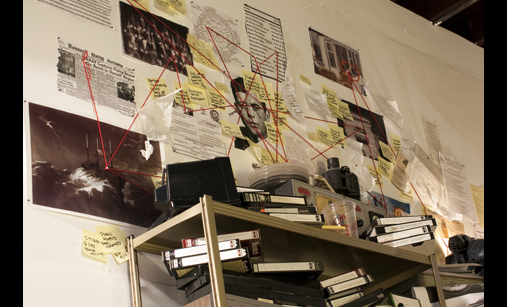

That said, here’s an idea of what’s in store: The massive, 12,000-square foot installation of Why We Do This has been set up like a film, with one scene butting into the next, but the viewer gets to have a hand in making their own narrative as it unfolds around them. A user-friendly art show, each scenario you come across begs involvement, direct audience participation — so much so, that it’s near impossible not to accept the invitation to touch, dance, run, swing, shout, crawl, climb, pull, pop or bounce, at least once while as you’re “seeing” this exhibition. I can’t imagine how one could remain entirely aloof from the pleasures of everyday living the artist has put on show for you here; even skeptics are sure to crack a smile at some point wandering through this lively maze.

And how did all of this come to be at the Soap Factory this fall? Who is responsible for such shenanigans going on in the gallery? A team of many people worked to build this funhouse environment, under the direction of artist Andy DuCett, with production oversight by the Soap’s director, Ben Heywood. Few artists have attempted to fill the whole gallery in this way; the Soap Factory is one of the largest contemporary art exhibition spaces in the nation and, for the artist, having such expanses to work with is both a luxury and a challenge.

DuCett’s previous practice has involved creating assemblages of found domestic objects; it’s possible he could have filled each room of the Soap Factory space with his wall-based, discrete sculptural conglomerates, accompanied by some of the 2D black-and-white line drawing creations for which he’s also known, images of mish-mash worlds recombining elements from everyday scenes. So, yes: DuCett could have simply filled the gallery with more of what he has made and shown already. But given two-and-a-half years preparation time, the artist’s practice began to move in different directions. Site-specificity, creating art to be viewed only in the place for which its made, is the main catalyst for such departure in DuCett’s practice. And this shift in focus has pushed his work into the realm of “participatory art,” even “relational aesthetics”. Both these new(ish) trends in art forgo the creation of a set of aesthetically distinct art objects; rather, the artist produces scenarios for human engagement, placing the primary aim of the work on its ability to extend out, beyond the world of the gallery and into the real life of the viewer/participant. And if this was the ambition driving the creation of Why We Do This, DuCett undoubtedly achieved his artistic goal.

______________________________________________________

It’s impossible to resiste the work’s invitation to touch, dance, run, swing, shout, crawl, climb, pull, pop or bounce, at least once while as you’re “seeing” this show – even skeptics are bound to crack a smile while wandering through DuCett’s lively maze.

______________________________________________________

WHEN HE DESCRIBES the inspiration for the show, DuCett says he focused initially on the old industrial ghosts of the Soap Factory, all the mundane factory work previous generations endured there. Then DuCett found himself thinking of all the enjoyable, outside-of-work diversions that might have gotten those workers through their miserable days on the line. And in fact, a laundry list of such leisure activities common to middle- and working-class Midwesterners provides a fair overview of the scenes on show: canoeing, hiking, vintage shopping, beer drinking, football games, ice fishing, heading Up North to the cabin. Thrown in for good measure are some levelers to round things out, universally beloved, regionally non-specific pastimes including: popping bubble wrap, walking the dog, taking a shower, swinging at the playground.

DuCett makes art about play that’s so genuinely fun-loving there is a coalescence of form and content you don’t find in more traditional modes of work on the theme of play (e.g. paintings of kids at play or of fishermen casting a line). In Why We Do This, the playtime itself is activated; the theme of play is not represented but embodied by the viewer, who’s invited into the scene — onto the swing, or to jump on the cabin bunk bed.

The reactivation of childhood play, combined with the pervasive, muted color tones of accumulated objects of the 1960s and ’70s, creates a strong theme of memory. At face value, one might read the show’s assorted vignettes as products of the artist’s own past. However, the viewer isn’t intended merely to be a spectator but a participant in these scenes; in other words, the artwork is poised to trigger your reminiscences, rather than just recount someone else’s. In addition, the shared quality of the memories showcased here, like star-gazing or flying in a plane, indicates the aim is something much bigger than merely putting a viewer inside specific episodes from the artist’s life.

Nostalgia, as a peculiar mode of rose-tinted memory, creeps into every scene: the 45 of Sinatra spinning on a kid’s suitcase turntable, the dive bar stocked with vintage beer cans, the record store, the extra-large Battleship game (not the new electric one that talks to you), and the sky-high shelves filled top to bottom with National Geographic magazines (and not a Kindle in sight).

Lest you think otherwise, DuCett’s use of nostalgia isn’t just cheap and sentimental yearning for some idealized past. Indeed, the artist preempts such critique by erecting red flags here and there in the show, incomplete installations left derelict, signs of imperfect, unfinished memories, perhaps. And punctuating the vignettes are cartoonish, black-and-white line drawings of vacuums or radiators; they serve as persistent reminders of the constructed, fake reality, or at least not-quite-reality on view all around. This mirrors the way our memory actually functions, contaminated by all sorts of filters and abstractions.

DuCett’s emphasis on the common spans multiple meanings: the common way we store memories, the common consumption of mass-produced culture, the common need for sleep (and even a shared tendency to drool, as witnessed by the wall of unsheathed pillows). And by being here, in the Midwest, we are in a sense culturally common as well. This is an installation for us, we who live in this place. Rather than creating with an eye on the New York art scene, DuCett gives high-five to the Midwest, celebrating why we do this: why we live here, why we create culture in a supposed artistic backwater.

Despite this celebratory, State Fair sounding theme, DuCett manages to push viewers beyond their comfort zones by, oddly enough, pushing them out of the local social norms. Confronted with the sheer fun of his installations even stodgy, prone to complain, not-sure-I-like-this Minnesotans are transformed into smiling gallery goers.

As a contemporary art historian, I’m fascinated by the way DuCett upends traditional ways of seeing art for one especially well-suited to the 21st century; it’s a mode of seeing where unmediated social interaction can be what art does, instead of “sit on its ass in a museum” as Claus Oldenburg has aptly said. It’s a vision of art where camaraderie and genuine human connection take precedence over the creation original art objects, alone in a studio and for purchase by individual collectors. To that end, DuCett’s best artistic tool is the coercive power of his wacky, fake, totally appealing environments – he makes worlds like the one you know (or think you remember). Engaging in his work is so easy, so natural, that the relational aesthetics underpinning DuCett’s larger vision go down easy, as if covered in chocolate-candy coating.

DuCett also manages to work well with the force of contradictions, lacing oppositional forces inside what seems unified and contained. And guess what? I’d argue that’s precisely what makes for great art in our era — this mixing it up, this blending of grandeur and the commonplace, universal and specific. And his emphasis on active viewing and participation leaves room for individual viewers’ shifting, constantly evolving and hybrid experiences of the work. DuCett dishes out tons of fun and heaps in, literally, tons of stuff for Why We Do This, and in so doing he gets the average Minnesota local, unwittingly, to participate in cutting-edge art.

______________________________________________________

Related events, links and information:

Why We Do This is on view at the Soap Factory in Minneapolis through November 11.

There will be a closing reception-cum-estate sale on November 10, from 7 to 11pm. After the three years of planning, building and collecting things for the installations in Why We Do This, the closing reception and estate sale is an opportunity for the many objects within the show to disperse once again. In addition to the thousands of National Geographic magazines, LPs and amazing thift-store finds, DuCett will also be selling some of the custom-built objects from the show. Popular exhibition items like the giant six-pack, his Vermeer reproduction and larger-than-life game of Battleship will be for sale as well. At the closing reception you can take a red rose and have your photo taken with “Fabio,” grab a beer from the small-town bar, or run onto the football field through the players’ tunnel showered in cheers and high-fives from your teammates.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Sheila Dickinson is an adjunct faculty member at the College of Visual Arts in art history. She recently received her doctorate from University College Dublin, Ireland in contemporary Irish art theory.

However, the viewer is no mere spectator, but a participant; the artwork is poised to trigger your reminiscences.