On Learning Something Old

Searching for the stories that baskets tell: spanning craft, geography, lineage, and how they are used in daily life

I once spent a year observing a basket in its daily use without knowing the profound effect it was having on me. I watched it get dirty from hands and tools and coffee spills. It collected dog fur and dust from the job site. It saw rain and snow and wind, developing its own patina. After a full year of hard use—having hauled lunches and thermoses, extra tools, books, and sweaters—the lashing around the rim broke. As I stood at the kitchen counter one spring morning looking at the torn, narrow lashing, I felt in awe of its strength. In this instant I knew I needed to weave a basket of my own.

I don’t know why the pull to weave was so strong. I had made other useful items with my hands before. Mukluks and makizinan were custom-made for my feet and for those of my babies; I strung beads into intricate patterns to create necklaces, and peyote-stitched adornments to eagle feathers or lanyards that held car keys. Perhaps this felt different because I was working with raw material that had been pounded from a living being, a live black ash tree, just two days prior. I was cutting this material, now referred to as “splint”; I was wetting it in a basin of water to make it pliable; I was laying out limp pieces of summer growth, giving shape to what was once a two-dimensional thing. My mind was blown by the process.

On a spring day in 1999, I wove a basket on a three-legged table in my front yard while my two small children played in the dirt. I finished weaving eight hours later, and left it to sit outside for the rest of the day and all through the night, catching glimpses of it before bed and again in the morning light. Something about working with this particular material and weaving my first basket woke me up.

From 1999 to 2000, I raised babies and wove baskets, one right after another. This first basket was my favorite—the next four I didn’t like at all. But I started to get the hang of it. I rented a few books from the library and found a few videos about the process. I came to know what looked good to me, what seemed the most useful. I learned how to make baskets through the process of weaving them.

After that year, a community member approached and asked if I would teach a class. I told them no—that I didn’t know anything. They told me to just share what I did know. So I did. In the fall of 2000, I taught my first class.

I also kept weaving.

What started as making simple baskets turned into manipulating the shape through tension. They started to get wider and taller; sometimes they were woven out of thicker splint so as to hold heavier loads. Incorporating green woodworking techniques, wood billets were riven out of ash logs and eventually carved down and steam-bent into useful shapes, creating handles and outer rims and skids for market and garden baskets, laundry and pack baskets. Baskets became my mainstay. I couldn’t get enough of learning from and making them.

Connecting with ash in this intimate way, I wanted to do more than just weave with it. I wanted to know its geographic habitat—where it came from and who the original ash weavers of this continent were. I wanted to know that this craft was connected to my ancestors, and not an idea I was trying to force into being part of my own history.

The Ojibwe word for “ash” is aagimaak, and it means something along the lines of “bending wood.” The word for “black ash” is baapaagimaak, meaning “pounding wood” or “beating wood.” These are old words. Considering that the Anishinaabeg lived so closely with the land and received all life from Mother Earth, I am certain they knew what wood could do. Why else would these trees be given these names?

As I looked around my reservation and others here in northern Wisconsin, I was having a hard time finding any Indigenous ash basket makers. I was looking for a connection, a human person, a story, a basket. I identified two individuals, but my plans to meet them never materialized. One of them—a young man who had picked up the craft a year prior—had moved to the West Coast, and the other was too old to share her knowledge with anyone. I wondered if her hesitancy to meet had to do more with her feeble health or her own sadness in knowing that she was one of her tribe’s last weavers.

Regardless, I had learned much in the process of searching. Considering my ancestors migrated inland from the East Coast pre-contact through the Great Lakes, it was no wonder I found hundreds of baskets along their route, from Maine all the way to Madeline Island in Lake Superior. I learned about the nuances in these styles, and the embellishments and knifework of the various tribal groups that worked with their own native ash tree species. I came to understand that, between the two main types of work, fancy basketwork and utilitarian basketwork, I belonged heavily to the latter.

Tribes all along the Great Lakes have their own stories about baskets. With each community I visited, I would always ask questions of the people there. Stories started to surface. There was an elder who had a few black ash baskets that were handed down by his grandmother. Another told of an elder who had his eagle feather headpiece—handed to him by his father and grandfather before—stored in a basket that sat about two feet tall, with a woven lid to fit. Another elder reminisced with me about how he was asked to pound a log for his aunties when he was about 16 years old. He told me it was the hardest work he had ever had to do and never wanted to do it again—so he never did. He was about 62 at the telling of this tale, which meant he would have been pounding a log on the reservation back in the 1950s, a generation before I was born. These stories helped support the answer I was looking for: my people did, in fact, weave black ash baskets in the past—they just hadn’t woven any for a while.

As I write this, I am reminded of the day I sat looking at old photographs given to me by my last living great uncle. His English name was Clarence Hillary Connors, but he was known to everyone as “Happy.” I noticed something in one of the pictures I had not recalled seeing the first time around. I usually just took note of the people, how they were dressed or how poor they looked. But this one day, I saw a black ash basket sitting on the porch behind who I thought to be my grandmother, Martha, being held in the arms of her mother, Margaret. What I could see was this handmade black ash splint work basket, with two handle spaces just under the rim system, for carrying items. I had possessed these pictures for almost ten years and I didn’t even know it. There is no way of telling who made the basket or how it came to be on the porch of my great-grandparents’ home, but I like to dream that maybe my strong pull to work with this material came from one of my earlier female relatives. Maybe it had been in my blood this whole time.

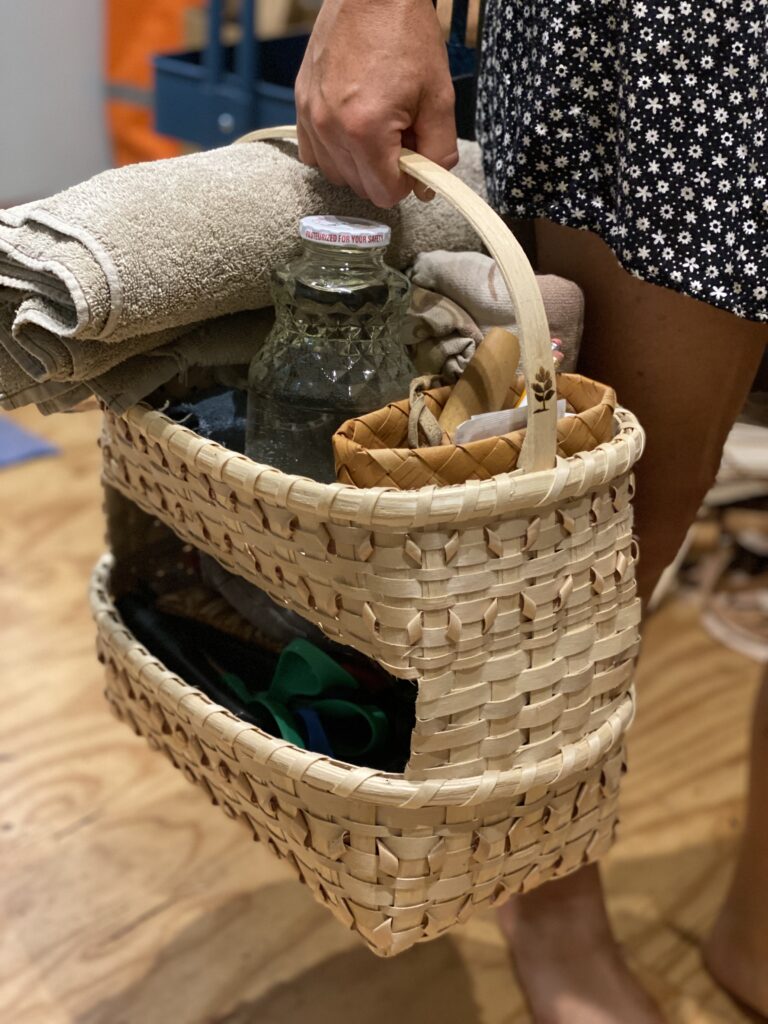

Today, there are baskets hanging from my kitchen ceiling used for hauling, cooking, and harvesting. I take baskets everywhere I go: to the grocery store, the market, the beach, to ceremony. Perhaps it is with the hope that people will see this simple act—of carrying a basket filled with that which I need—and start to remember that there was a time when we all used baskets. (My secret hope is that the basket prompts them to want to weave a basket for their own everyday use). Elders in particular know this, for they are not as far removed as the younger generations are from basket use. It’s common for me to be out and receive a compliment from an older person, or from a person with roots in other countries, who says, “I love how you use your basket,” or, “My family uses baskets back in _____.”

What started as weaving to have a finished product turned into weaving to learn about patience, humility, respect, love, courage—all of those fundamental lessons designed to teach us to be kind and gentle beings on this Earth, and to teach us about ourselves and each other. To help us to get along. To promote balance. This work allows those of us engaged in the basket-making process to change and grow, right in the moment. It allows us conversation, laughter, and stories. It allows us to look at the world differently. It allows us to heal.

As helpful as books have been throughout my learning, they are just books. I cannot pick up the baskets I see in photos to inspect their undersides. Old baskets are great teachers, and I knew I needed to visit them. This realization led me on an adventure in 2016 to museums on the East Coast, where I not only met some wonderful collections stewards, but also some astonishing baskets.

Within a number of museum collections, I picked up baskets I had longed to hold. I was able to track where they came from and where they disappeared to. I photographed colorful stamping on some and embellishments on others. Cut marks, seams, the points where lashings ended and began, material that was made with slitting gauges and those made completely with a knife—all was easily viewable. Being present with these baskets, I could tell which direction they wove. I could see that baskets were like a painter’s palette. In some instances, it was as if there was no rhyme or reason as to why part of a technique was finished in the way it was—that it made sense to the maker and that the material was comfortable was all that mattered.

I sensed that these baskets were made by people with critical thinking skills, and in forgiving ways. I wondered if I could tell if a basket was made by a man or woman—so few were left with some sort of maker’s mark that it was hard to trace a person’s path as a basket maker. This led me to the understanding that I would need to brand my baskets in case they ended up in some sort of museum collection in the future. In this way, people would know who the craftsperson was and perhaps be able to understand me as a person, and my philosophy or connection to the material through the quality of my work.

An in-progress basket made in the cat’s head-style, which sits on four corners. Photo courtesy the author.

A double-decker tool basket in use. Photo courtesy the author.

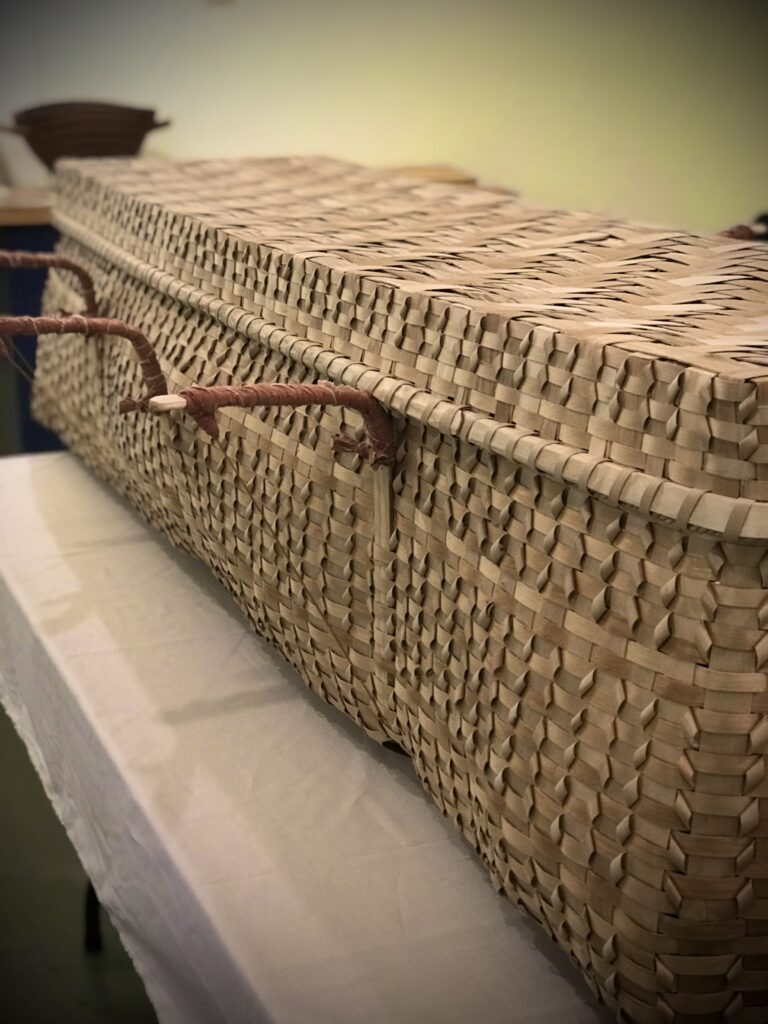

A casket made of ash that Stone wove in 2017-18 to bring attention to the emerald ash borer. Photo courtesy the author.

Learning from old baskets and basket-making tools was a game-changer—as was having meaningful conversations with those I met in the museums I visited. Being in the presence of collection managers as I fondled the baskets and talked about how they were made or used prompted a sort of call and response between myself and these museum workers. Inquiring about how something was labeled, or the material it was labeled as being made from, led to deeper conversations. Combining my working knowledge of natural material identification with their knowledge of artifacts and history sometimes aided in more properly identifying such things. It was not uncommon to hear how much collections managers appreciated visits from folks like myself: academia entwined with boots on the ground.

During a different visit to Chicago’s Field Museum, the baskets I wanted to view were part of an actual exhibition. They sat behind glass—beautiful, but untouchable. I thought about the people who visited this museum and wondered whether the general attitude towards baskets was that they were things of the past, never to be used again. I wondered if that was all a basket was good for in this day and age, and if this is why so many humans have turned to paper and plastic. Had we forgotten that all cultures around the world wove baskets using the natural materials that grew there—and still do today? Had we forgotten that basket-making is in all of our DNA?

The sadness I felt from this thought evoked a conversation with a curator from the Field Museum about how we think of baskets today. Our conversation kept up through lunch and the second half of the day, when it was time to visit a different part of the museum’s collection. At this point, I asked her to help me carry my personal basket. In a way, she did not know how to respond to this request. She very carefully held its flexible splint-wrapped handles, cautiously moving up and down the stairs, and in and out of the elevators. She treated my everyday, heavily-used basket like royalty. Eventually, she asked questions about the different color splints that had been woven here and there along different parts of the basket. We talked about basket repair and how, with time and experience, repair becomes another layer added to the whole concept of basket use. These were conversations I do not believe she ever had before.

Towards the end of our day together, the curator led me down a corridor to see a basket that had been newly acquired for an upcoming exhibition. In that room I saw paints, brushes, and other materials on the shelves. I recognized it as some sort of repair department—a department for a different kind of repair than the one I practiced. There were a few employees present, one of whom was touching up colors on an older piece, trying to get it to look almost new again.

I asked questions of the museum staff about this “touching up” of old objects. I shared how, in contrast to this restoration, old baskets are teachers that I learn from. I told them that wear and tear tells stories, and that stories provide direction. I told them that, as a basket maker, I heavily rely on these stories, as they help me to learn about how something was done in an earlier time. Studying old baskets helps me understand my ancestors, as all the old basket makers are dead. Such baskets help bring their mindsets to life. I told them that, if they are altered or repaired, these stories are changed forever. In this room, more conversations were being had for the first time.

Our visit being at its end, the last place I walked with the curator was through the new, yet-to-be-opened exhibit. It was in this space that she shared her desire to have me return in the future, bringing along an assortment of baskets: both new and old—and repaired. These would be baskets that people could touch and hold. They would not be behind glass.