ESO MALFLOR Plays with Fire

Tending to questions and complications in the solo exhibition The Earth is a Body in Transition

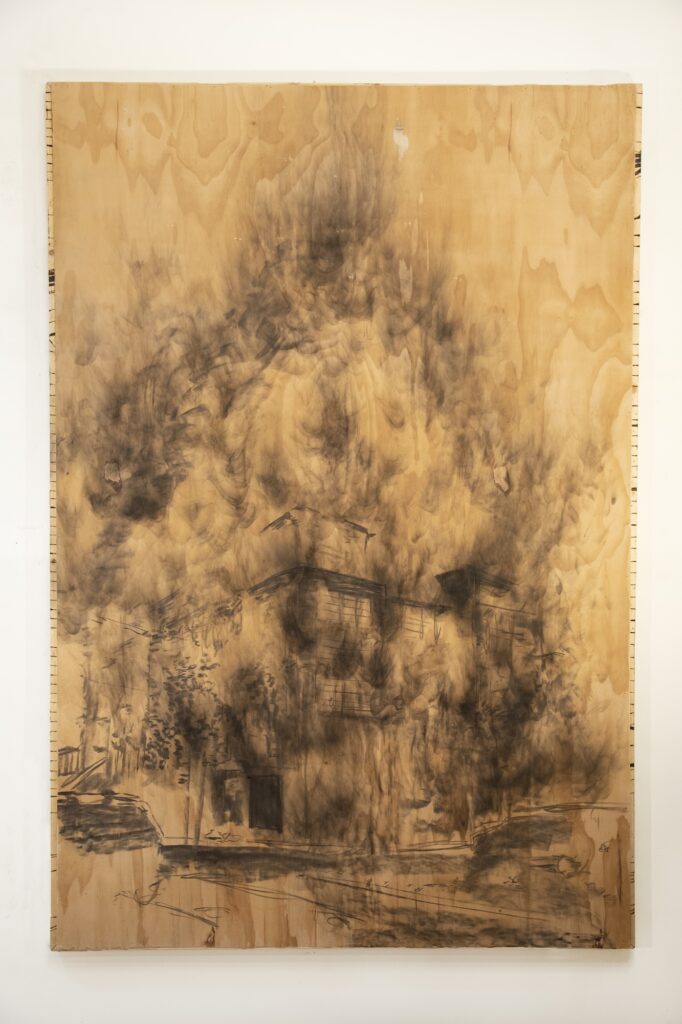

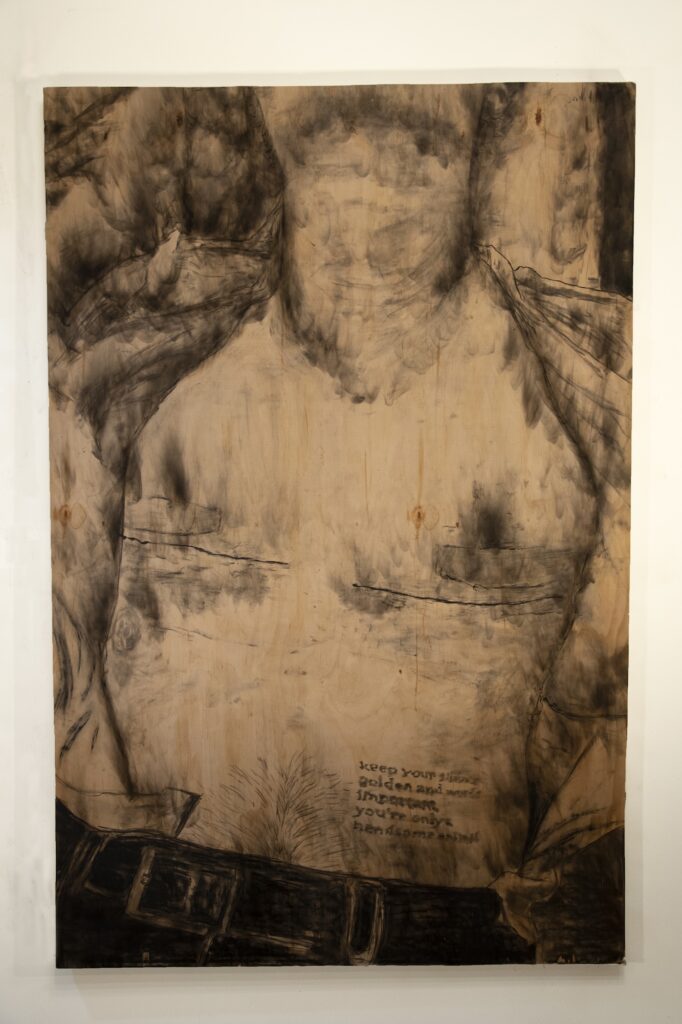

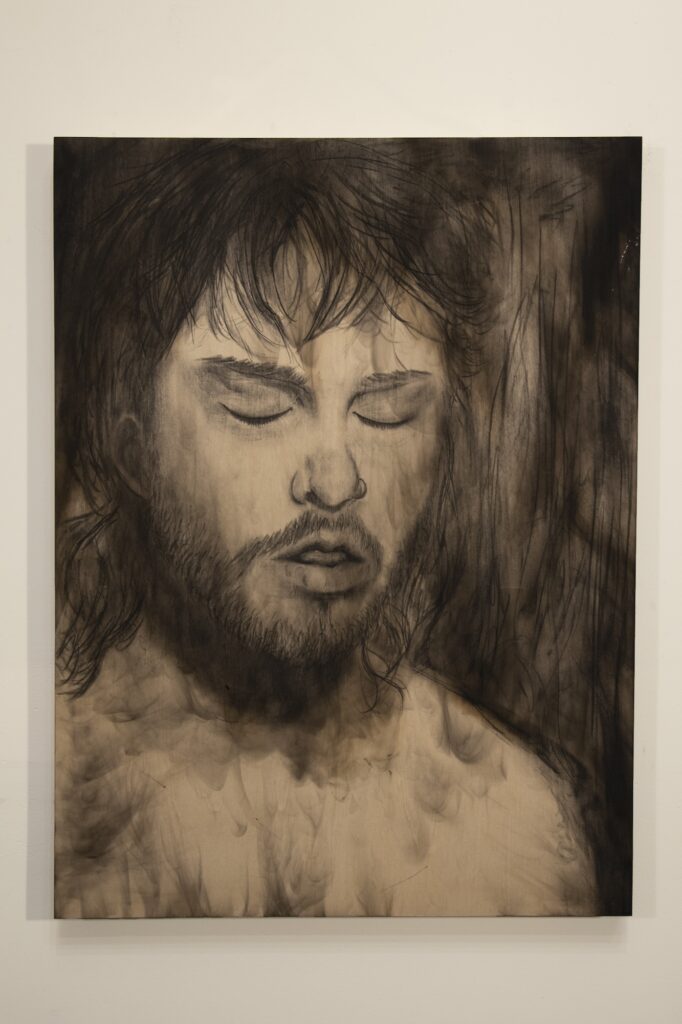

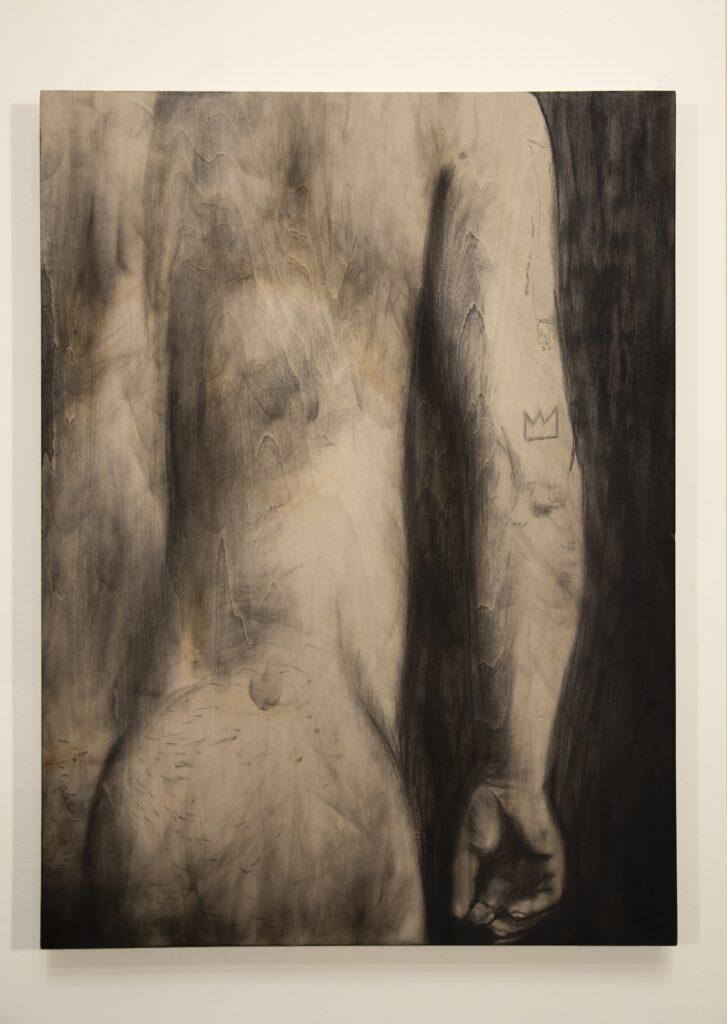

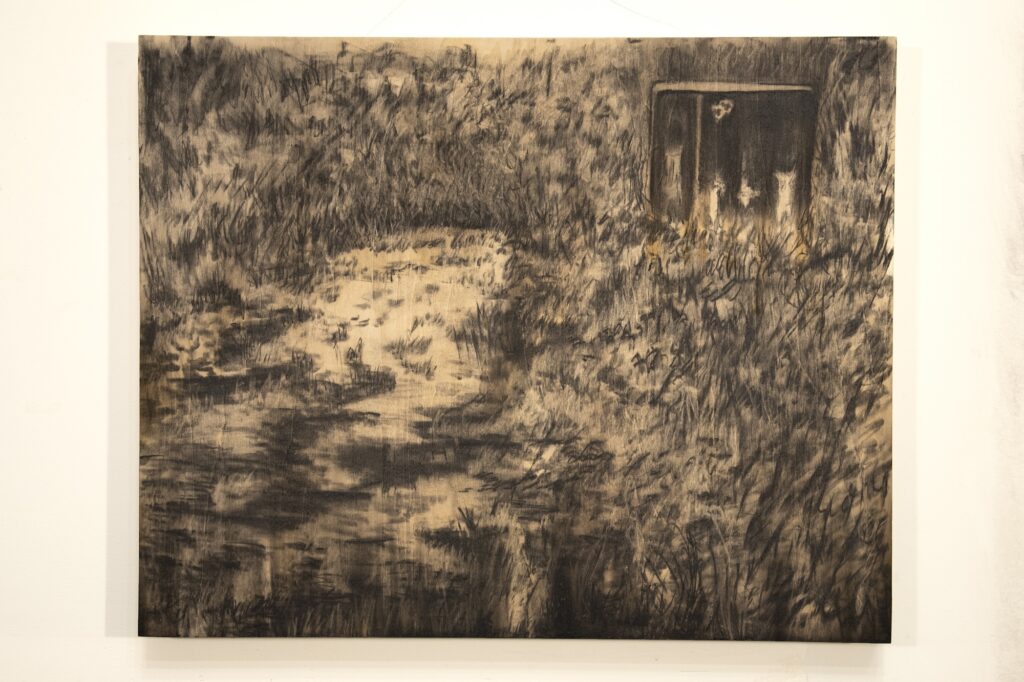

In their solo exhibition The Earth is a Body in Transition, MALFLOR makes drawings with the soot, resin, and charcoal left from burning sticks of palo de ocote, which is Spanish for pine wood. Black lines and smudges gather into bodies, landscapes, or topographical maps. The hand-drawn marks contrast with the delicate haloes left by the licks of flames: Feathery, they seem to dance across plywood, paper, and the wall itself. Fire acts as a complex metaphor for transformation in this body of work, where a palpable interest in exploring elemental materials–fire, limestone sediment, bones, wood, and even the charred remains of a building–produces a formally tight but conceptually complicated conversation.

Thematically, the works pivot from the planetary to the personal, from scenes of public protest to private rituals in ancestry and belonging. The overall effect resembles scrolling through a social media feed where worldviews are at risk of turning into algorithmically amplified bubbles. The Earth is a Body in Transition is no exercise in woke whateverism, though. In the wake of my encounter with the exhibition, I found myself surrounded by a whirlwind of questions–mostly questions about care and complicity. Quaint questions, possibly–this is 2024 after all and Trump has just been elected to a second term by a majority of Americans. Still, I can’t help asking anyway. After all, tending to questions and complications is a habit of care.

Complication #1: Place

In Minneapolis, the aftermath of fires can still be felt. MALFLOR deliberately connects their drawings to the uprising that happened in the wake of George Floyd’s killing. In a drawing titled Minneapolis’ Third Precinct (2024), the police station that burned on May 28, 2020, is shown engulfed by flames. Materially, MALFLOR’s plywood panel echoes the eruption of public art in the summer of 2020, when boarded-up store fronts became canvases for street artists and communities united in outrage and grief. Many of those murals have since been collected and archived by “Memorialize the Movement,” an organization led and founded by Leesa Kelly. Though the murals have been exhibited in galleries, none of them are for sale: They are a people’s archive. As a long-time resident of South Minneapolis, I pause seeing MALFLOR’s drawing in a South Minneapolis gallery. What does the work do here? What does it aim to do? What happens when protest becomes precious art punk?

And it is worth noting that MALFLOR would not be alone in commodifying protest: Sam Durant, an artist with local notoriety, exhibits light boxes that feature slogans based on protest signs from around the world. Rirkrit Tiravanija draws people taking to the streets in march after march after march. Andrea Bowers, in still and moving images, creates homages to environmental activism, feminist resistance, and migration politics. All of these works are probably rooted in sincere concerns, well-intended, and in passionate support of the cause du jour–and they take a risk: Protest becomes exchangeable. Expected. Exhausted. (Jacques Ranciere’s analysis of Josephine Meckseper’s photographs of scenes from anti-capitalist protests makes this point perfectly clear: Images of protest participate in the same machinery of image production and circulation as the ever-ravenous news media. Simply put, protest sells. The question: Is that a problem? Does it lessen the urgency of the work–or does it compromise the myth of the artist as a kind of embodied social conscience?

MALFLOR includes a second protest drawing: Al Quds Day Protest (Iran) (2024) shows an American flag go up in smoke. The occasion: an annual pro-Palestinian event on the last Friday of Ramadan. The question here is not whether Palestinians need support; they do. The question is what the drawing, based on a photograph found online, does. What do these moments of social unrest, burnt into plywood, reveal–other than to signal, “I have seen this and I care”? Do they burn into memory what otherwise might get lost in endless scrolling?

A found sculpture titled Chicago & Lake (2024) accompanies the protest drawings. The artist retrieved the charred remnant from the rubble of a warehouse that went up in flames in the early days of the uprising. On a pedestal in the gallery, it now stands as a haunting specter of civic unrest. Is it quaint to ask what the ethics involved in this appropriative gesture might be? Or to ponder who capitalizes on what here? Or how and why this found object could read as ruin porn?

Complication #2: Care

The Earth is a Body in Transition: The title of MALFLOR’s exhibition states a fact. The planet is warming. In two drawings, Fond Du Lac and Helderberg Nature Reserve the artist shows fire as a force shaping the land–whether in a controlled burn in South Africa or a forest scene on a reservation. Based on found online photographs, the works show fire as a force for good–not out-of-control wildfires but wilderness management, intended to replenish the soil for future flourishing.

The Earth is a Body in Transition is more than a profession of care for the earth as body, though. In their artist statement, MALFLOR writes, “I create material, ritual, and visual parallels between the human body and the earth body … the paintings and installations in this exhibition explore the relationship between trans bodies and the earth.” Nowhere is this drawing of parallels more evident than in Micah, a portrait of a trans body, cropped to a torso, where scars, like fault lines, are rendered in black and cut across a bare chest. A post-surgery body, represented as if it was yet another landscape to control, manage, mold and shape. And maybe that is a helpful analogy; maybe it isn’t.

MALFLOR is not the first artist to project their life experiences onto the planet: finding such kinship may make us care, after all. Consider Alexis Pauline Gumbs’ analogy: She likens globally rising temperatures to menopausal hot flashes. This planetary menopause, though, is not an organic part of aging and hormonal reorganization but the result, she writes, of “toxic human actions.” I am less interested here in the intricacies of the relationship between environmental health justice for aging women and global warming–and more invested in asking why we need to anthropomorphize, to find likeness, in order to care.

MALFLOR’s analogy, too, courts similitude to forge a sense of intimacy: The earth is a body, yes, and in transition–but there is a point where the comparison falters: Unlike a trans body’s transformation through surgeries and hormones, transitions which involve making choices, the planet has no say in how our human choices engineer its future.

What I want to ask at this point is simply, do we need to find likeness to care? Do we need to see hot flashes and gender transitions reflected in the planet’s changes to give a shit? Does empathy need similitude–or can care manifest not despite of but because of genuine, irreducible, unapologetic difference?

These are not isolated questions but concerns that jostle in the public imagination right now: Aruna D’Souza’s little book Imperfect Solidarities, which came out in the summer of 2024, is a case in point. Drawing on Edouard Glissant’s work on opacity, she questions the need to translate difference into terms that are familiar, that is, legible to those who hail from privilege. For Glissant, reducing difference to similitude and insisting that difference be rendered transparently, constitutes a kind of violence, the anti-thesis of care.

Complication #3: Land

Nowhere has this violence been rejected more thoroughly than in Indigenous organizing and decolonial practice. Rather than explain themselves in terms that settlers can grasp, Indigenous artists and thinkers insist on the right to refuse such endless exercises in catering to the colonial mind.

In As We Have Always Done, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (Alderville First Nation) expands this generative refusal into a theory of resurgent organizing: “Resurgent organizing … has to be concerned with building a generation of Indigenous nationals from various Indigenous nations who think and act from within their own intelligence systems; who generate viable Indigenous political systems; who are so in love with the land, they are the land; who simply refuse to stop being themselves; who refuse to let go of this knowledge; and who use that refusal as a site to generate another generation who enact that with every breath, birth, and political engagement and in every moment of their daily existence.” Imagine–a people so in love with the land, they are the land; not separated by ownership, the logic of resource extraction, and proprietorial relations, but simply loving so hard that they are the land.

While Simpson’s call reaches far beyond the logic of analogy and is specifically directed toward Indigenous people, Kaitlin B. Curtice (Potawatomi) writes in Living Resistance: “repairing our relationship to the land and the water, no matter who we are, is an essential part of living resistance and affects every part of our inner and outer world and life.” This urgent work of repair, this quest for remembering long-lost connections and practicing being-in-relationship-with is part and parcel of decolonial practice. A longing for connection to land and water is a deeply felt part of MALFLOR’s exhibition as well.

To find this work, you have to go down to the basement level of the gallery. This descent underground, even if it is entirely a matter of practicality, is ingenious nonetheless: Down below–underneath what’s rational, reasonable, and putatively enlightened–a different kind of kinship manifests. Underground, roots prosper, and ancestral ghosts of DNA whisper in our genes. Topographical lines, rendered in black charcoal and soot right onto the wall, their outlines fanned by flame, situate us in northern Norway, above the arctic circle, in a landscape sculpted by glaciers. The closer the lines, the steeper the terrain. Yet MALFLOR’s drawing offers no clue about orientation: mountain or abyss, maybe both, depending, always, on where you stand.

Three drawings on wood panels hang as a loose triptych across the contour lines. On the right, a portrait of the artist’s face with a smooth stone between their lips; on the left, another portrait with another stone, this one held loosely in the figure’s hand; and in the center, a delicate drawing of a hole in the ground – an inkling that a deeper descent is still possible. The work feels like ritual, a symbolic return to the specter of homeland. In these drawings, bodies become part of landscapes. And more, they conjure a place-ness of their own: Curves and crevices of skin, along with the long dent of a spine and the bulge of a buttock suggest a fleshy topography. The body is place, understood as place. A drawing of their grandparents’ grave, Gravsted, solidifies the artist’s ancestral, nostalgic claim to this place.

But this claim to place, to ancestral connection, is complicated. Here’s why.

First, nostalgia for origins in a settler nation cannot help but be suspect. In The Future of Nostalgia, my fellow immigrant Svetlana Boym sees in nostalgia “a sentiment of loss and displacement” but “also a romance with one’s own fantasy. Nostalgic love can only survive in a long-distance relationship.” Nostalgia for European roots is a phenomenon deeply entrenched in US-American culture. In this exhibition, MALFLOR centers their Norwegian ancestry. The drawings and photographs pay tribute to intimate rites of return. Are they a romance with fantasy? Would that be a bad thing altogether? Or do these personal protocols of connection tap into the desire for belonging somewhere, anywhere? Belonging is never a given, though. Like kinship, belonging is a practice, a habit of care.

Second, there’s Norway, a place as complicated as they come. Once the rugged home of Vikings and fisherfolk, Norway in the 21st century has turned into a magnet for artists. Land art abounds along the scenic routes crisscrossing the land of the midnight sun. The art boom is largely funded by the government with proceeds from the state’s fossil fuel industry: Oil money pays for art. The paradox is hard to miss: New biennials in land art pop up and invite mindful proposals for how to interact with nature, ecology, sustainability. Artists make work to celebrate and collaborate with the earth and the elements, MALFLOR among them. At the same time, the industry that funds their creative endeavors is a major contributor to global warming and ecocide.

MALFLOR’s Norwegian land art–represented by two color photographs that document the slow decomposition of a body-shaped twig sculpture, somewhat reminiscent of Ana Mendieta’s silhouettes–is part of this paradox. Ephemeral and organic, the piece conjures connection, return, a funeral pyre not consumed by flames but transformed through organic decay. Visually, the photographs offer a lively counterpoint to the disciplined monochrome of the other works in the exhibition.

An ethic of repair and desire for ancestral connection to land thus turns to Norwegian arts funding in unapologetic complicity. And yes, ancestry is inheritance–ours to idolize, squander, or simply bear–but it is never as simple as a return to an elusive “home” where we might at long last belong. The work holds but does not address this tension.

Complication #4: Absence

“To be human is to be of nature,” MALFLOR writes in the brief statement that accompanies the exhibition. It is a simple yet profound insight, shared by thinkers and artists far and wide.

To name but a few: Kaitlin B. Curtice reminds her readers “that we are part of and not separate from the land we inhabit. … We are made up of the materials we see in the places around us, and we cannot undo the blood and bone that forms us.” We are, in the words of Vladimir Vernadsky, walking, talking minerals. Or, in Jane Bennett’s, we are all assemblages, complex confederacies of human and non-human actants inhabiting a body together: meet the body, a mobile ecosystem. When Bennett urges us to “live as earth,” to tend to the “‘alien’ quality of our flesh,” she points out that just in the crook of our elbow there live no fewer than six tribes of bacteria. “‘I’ is actually ‘we.’”

Bennett’s book Vibrant Matter, published in 2010, was part of the then emergent field of “new materialism,” though her research makes very clear that ideas about a vitality in materiality are not new at all. But looking at MALFLOR’s work, reading their words, you would never know. The ideas that the exhibition explores appear rootless, stripped of their own genealogy. Despite the global range of source imagery–from South Africa to Norway, the reservation, then Iran–MALFLOR’s work feels insular. Ancestry and genealogy only seem to matter when their own roots are concerned; the emergence of ideas is missing, as is any semblance of dialogue, texture, and exchange. Personal experience with ancestry is elevated to the point of an origin myth while context is most prominent in its absence.

This is where MALFLOR’s The Earth is a Body in Transition is at its riskiest: Myth makes marvelous beasts rise from ashes. Amid complicity and much complexity, a yearning for elemental simplicity makes sense. Fire, soot, charcoal and soil to the rescue: Let’s picture transformation–of bodies, nature preserves, social systems, and ancestral connections. My point is simple: These transitions are not the same. I am not sure what the work asks me to imagine other than shades of like-ness: as above, so below. Why is genuine difference so hard to tolerate–so hard to tend to?

Two sculptures, Amalgamation No. 1 and No. 2, stand out. They hold space for different forms of becoming.

Assembled from ceramic, wood, carved stone, and chicken bones, their blackened shapes still read as remnants but change how time moves through the work: No longer retrospective, reflective of social upheaval and reliant on digital source imagery to be translated into the idiom of fire, these forms suggest a future perfect. They gesture at what may-have-been. A slender, pointed black shape curves upward, where its hollow is met by another form of the same hue. A small point juts to the side, as if reaching, probing, while an organ-like bulge emerges elsewhere, caught unfolding. Together, the forms hover on the brink where organic meets inorganic. They refuse to be like one thing and not another, as they glide and nestle into each other, poke and probe and play in disciplined black. Prophetic and prosthetic, they read as charred relics of a not-yet completed creaturely mutation.

The sculptures are surrounded by an elegant cluster of flame drawings. At the heart of each drawing lies an absence–the ghost of an object, traced by fire, haloed in black. Steeped in ritual, these works hold space for what is absent. They do so beautifully. They make absence felt and depart from thinking through the lens of the human body in the throes of transition. Instead, they allow a different shade of queer weirdness to emerge: Creaturely, but not quite; lively but inanimate; prickly, bulgy, pokey, and delightfully strange.

There is no doubt that this is where the exhibition is at its finest.

The Earth is a Body in Transition was on view at HAIR + NAILS October 13 through November 10. More info →