We Fly: On Black Aliveness in A Picture Gallery of the Soul

Reflections on a landmark exhibition of Black American photography: on Black vernacular culture, its visual complexity and expansiveness, and the tie between collective consciousness and self-love

On a snowy night nestled near our wood-burning stove, I read The People Could Fly to my children. The beloved picture book by Virginia Hamilton retells the haunting folktale of the “flying Africans.” In Hamilton’s classic rendition, enslaved Black people begin to fly off the plantations upon hearing or reciting a few magic words. Growing dark lustrous wings, many fly away into the sky to freedom in a wondrous spectacle captured soulfully by illustrators Leo and Diane Dillon. Others remain, however, not quite able to access that long-lost gift of flight just yet—left behind to share this bittersweet tale of witness, wonder, and hope with each new generation.

Weeks later, as I walked through the exhibition A Picture Gallery of the Soul curated by Herman J. Milligan, Jr. and Howard Oransky at the Nash Gallery, I was reminded of flight, Hamilton’s flying ancestors, and the closing lines of a poem by Bayo Akomolafe:

I will be lighter than air. I will know the highway of blackness in its fluid ethereality. I will know how to fly, for what is my blackness if not the secret of flight?1

The exhibition closed in December 2022. It was vast, rich, layered. The curatorial choices demonstrated a deep understanding and reverence for Black time and memory and the expansiveness of Black lives and experiences. Writing about exhibitions is often bound by time and the urgency to review, reflect, and enter the conversation while the exhibition is still up and live. Yet, exhibitions never really “close,” do they? Their impact lingers, their contents evolve, enter new spaces and conversations, weaving meaning as they go. And in the weeks that have followed my visit to A Picture Gallery of the Soul, more ideas and connections, reflections, and meditations have unfurled for me about each artist and piece within the exhibition, as well as what exhibitions such as this one have to teach us about what it means and has meant to be a (Black) human being.

The work in A Picture Gallery of the Soul is evidence of a Black world—Black worlds, even. No evidence should be needed, and such proof is owed to know one. The photographs, their subjects, the artists all know this. They know that the gift of “flying” in relation to Blackness is also about the freedom to be and become anything, everything. It is also about the joy of beholding another Black person and being beheld in return…that sense of “I see you” captured in the familiar passing head nod of Black vernacular culture. That nod is of a Black world.

The totalizing violence of anti-Blackness has always sought to annihilate Black lives and Blackness by reducing it to one thing, one story, one identity, one experience, one image. Yet as scholar Kevin Quashie points out, in a world where white supremacy and anti-Blackness is total and totalizing, it is not total in the Black world to Black people.2 This truth seems to be at the heart of the exhibition, which affirms Black aliveness and its ability to hold the particulars and the multitudes of Black being. Quashie explores “Black aliveness” as an orientation to being human that is poetic, world-making, experiential, relational, vast, and roaming. He states, “We are not the idea of us, not even the idea that we hold of us. We are us, multiple and varied, becoming. The heterogeneity of us. Blackness in a black world is everything, which means that it gets to be freed from being any one thing. We are ordinary beauty, black people, and beauty must be allowed to do its beautiful work.”3

I sense the gravitational pull of a Black world’s orbit in the large sand dollar earring grazing Carolee Prince’s left shoulder. Her head is tilted sharply toward the opposite corner of the frame in Kwame Brathwaite’s photograph Untitled (Carolee Prince wearing her own designs). The monochrome photo is flooded in soft light. Prince glows—at once, the source of and keeper of the light. With her eyes closed, Prince withholds full access to her interiority. The elegant photograph spurns neat reading as the subject keeps to her own sanctuary and guards the sovereignty of her own soul. The perfect radial symmetry of the sand dollar, at play with the asymmetry of Prince’s leaning body, marks a quiet friction. It’s a whispered tension, almost imperceptible—a seeming weightlessness countered by the gravity of inner depths yet unseen. Brathwaite has captured Prince as a whole world, a whole beautiful being unto herself. Like the speaker in Nikki Giovanni’s poem “Ego Tripping,” Brathwaite’s photograph proclaims: “I am so perfect so divine so ethereal so surreal/ I cannot be comprehended/ except by my permission/ I mean . . . I . . . can fly/ like a bird in the sky . . .”4

And so, we fly.

In the exhibition, the photograph of Prince sat on the gallery wall mere inches beside a captivating self-portrait of Brathwaite himself. The two images paired together offered a gentle meditation on light, time, space and the role of self-regard in Black life and image-making. Often called the “Keeper of the Images,” Brathwaite chronicled Black life, beauty, and aesthetics during the Black is Beautiful movement of the 60s and 70s. His iconic images document an unapologetic Blackness reflected in the soul, style, swagger, and culture-defying/defining artistry of and for “the culture.”

In the group exhibition, the work of over 100 Black American artists was paired or grouped often a few inches apart. The arrangement was not strictly chronological, but rather relational. Images engaged each other across time, further underscoring the multidimensionality of Black lives, experiences, identities, histories, and futures that may coexist across the vagaries of space and time. The use of archival images in several of the contemporary artists’ work also served to underscore those entanglements of histories and experiences in Black life. The layout of the exhibition space was reminiscent of the photo gallery walls bell hooks describes in “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life.” In the essay hooks states, “To enter black homes in my childhood was to enter a world that valued the visual, that asserted our collective will to participate in a noninstitutionalized curatorial process. For black folks constructing our identities within the culture of apartheid, these walls were essential to the process of decolonization…these walls announced our visual complexity.”5

hooks and many other Black thinkers and artists have long asserted the central place of the camera and photography in Black life, and what it means to be in control of one’s own image-making and image-keeping in a world where racialization has always been intimately bound with aesthetics and visual grammar. The visual complexity hooks describes grants Blackness its fullness, its delicious propensity to spill over, its ability to be seen and understood as infinitely more than a mere monolith. This monolith is shaped by racism, and sometimes even a narrow logic of representation that insists on legibility and political recognition as a necessary strategy in the name of a Black public. It is an almost cosmic orientation toward complexity and expansiveness that I sense when I read the quote from Fredrick Douglass that inspired the exhibition’s title:

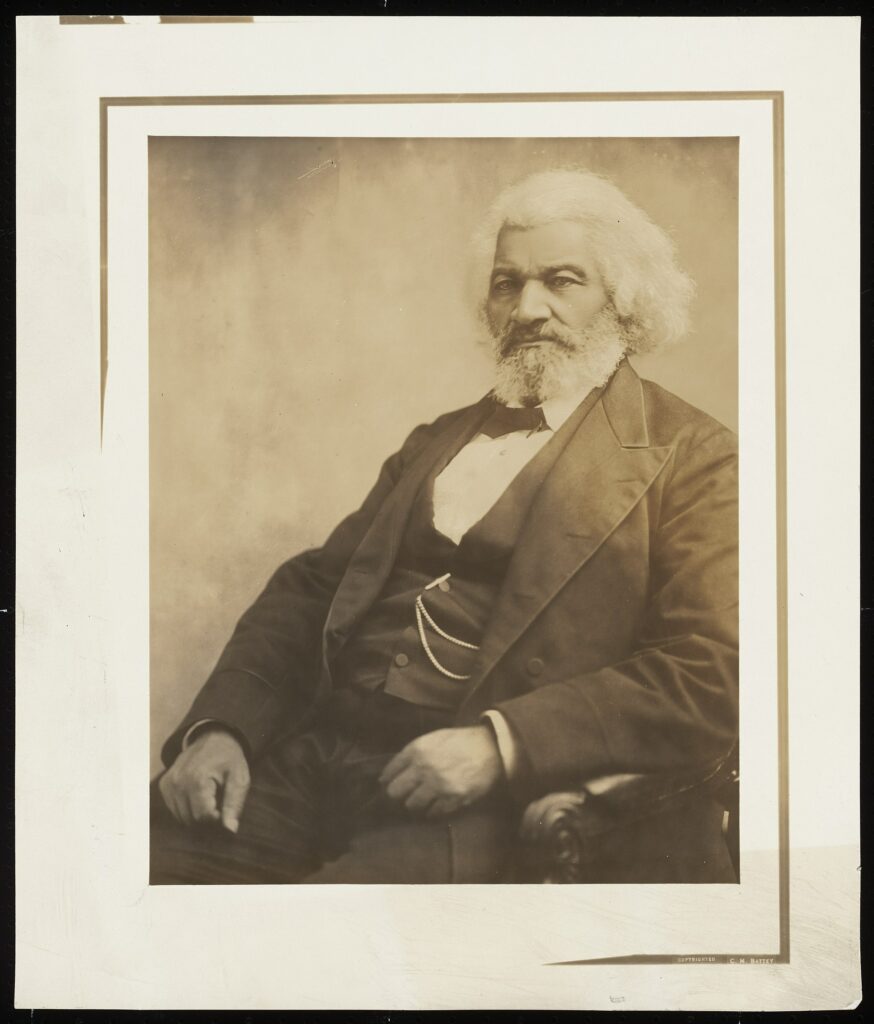

“Rightly viewed, the whole soul of man is sort of a picture gallery, a grand panorama, in which all great facts of the universe, in tracing things of time and things of eternity are painted.”

Douglass, a formerly enslaved Black person, was the most photographed man in the 19th century.

…Let that sink in for a moment.

He believed photography had the power to change the narrative, understanding just how much racism is about controlling image-making. Sitting for over 160 photographs, Douglass aimed to create an image of Blackness counter to the stereotypes and virulently racist caricatures peddled to generations of Americans that upheld white supremacy and rationalized centuries of slavery, violence, and racist terror.

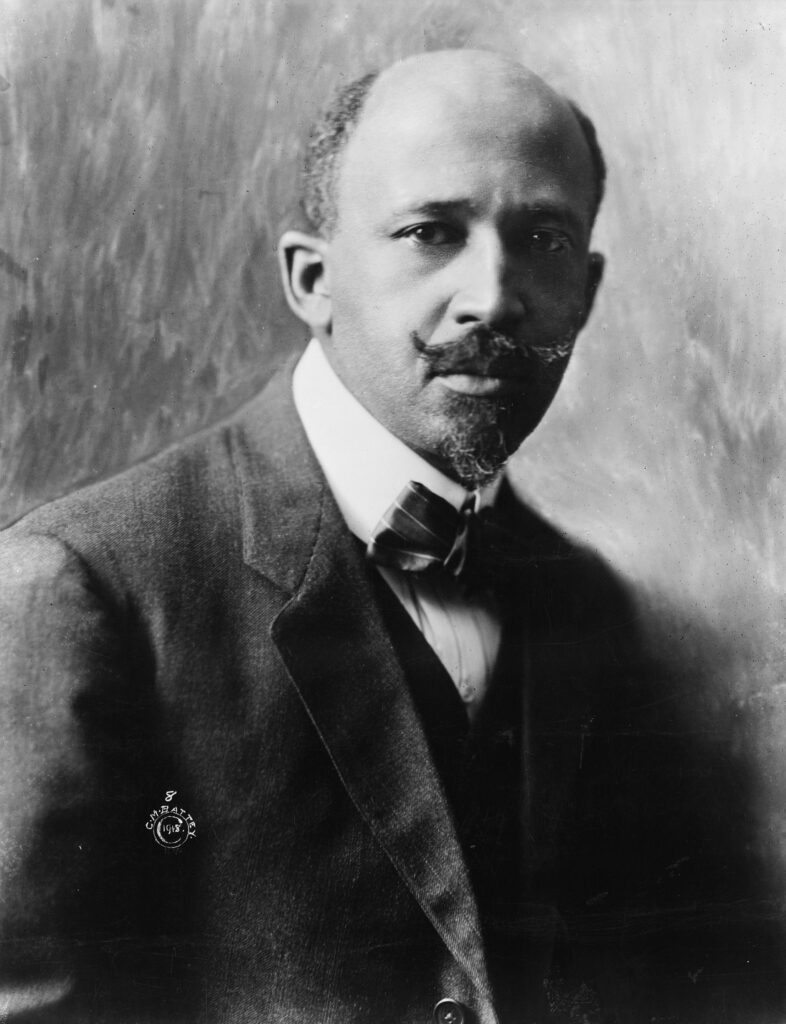

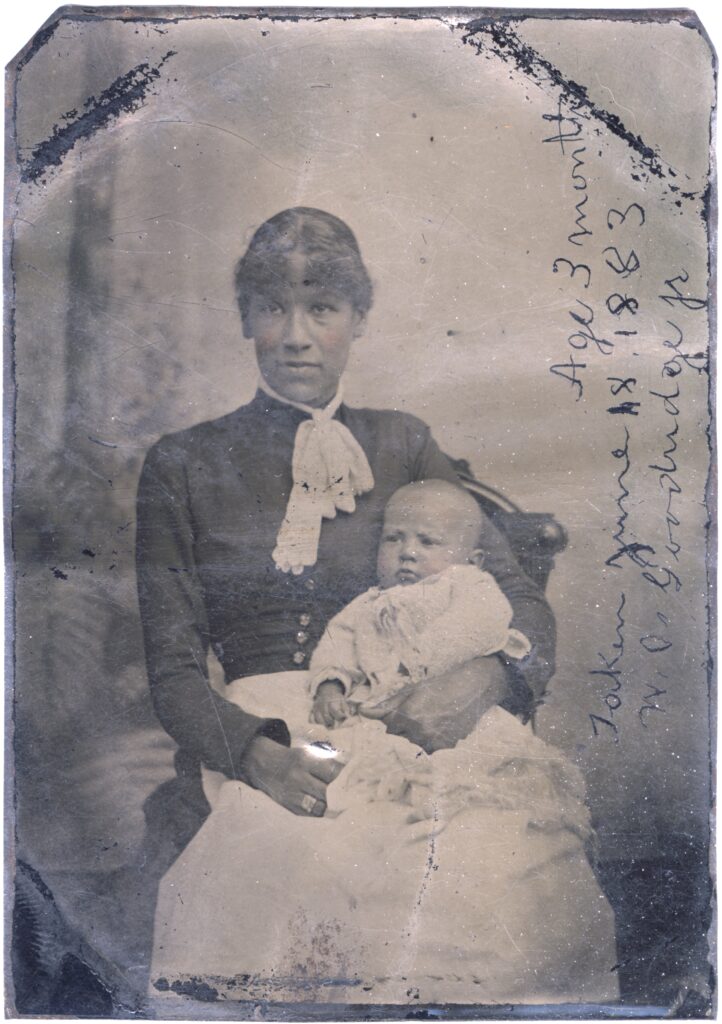

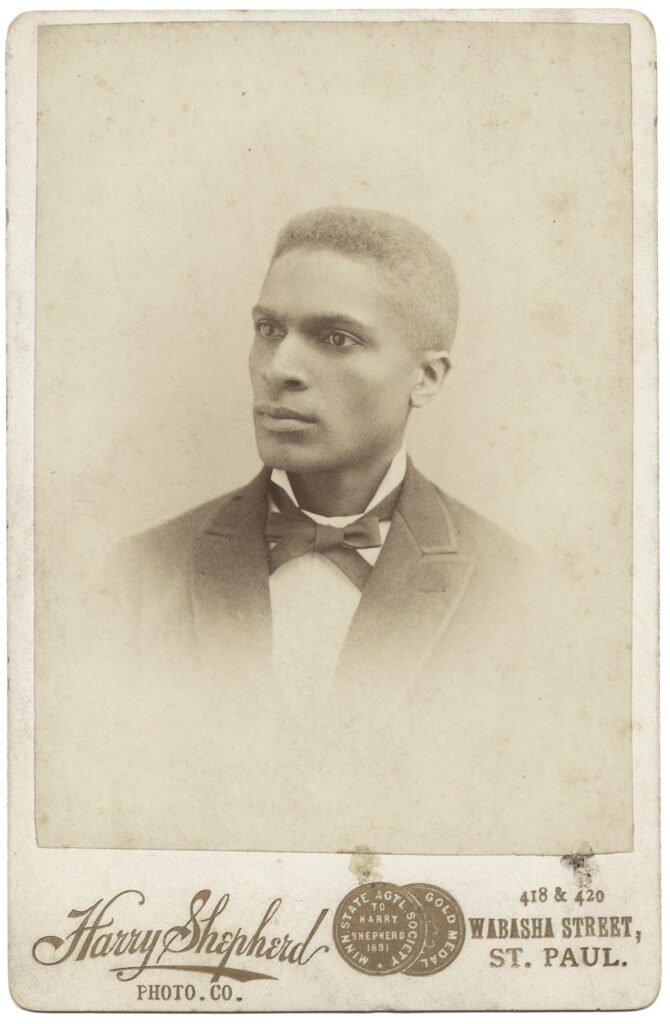

A photograph of Douglass was featured in the exhibition next to a portrait of W.E.B. Du Bois, both by C.M. (Cornelius Marion) Battey. Douglass is in his older years, impeccably dressed, regal and unsmiling. As a Black photographer, Battey presents Douglass in his full power and dignity. In her essay for the exhibition catalog, art historian Cheryl Finley emphasizes the radical role Black photographers have always played in documenting Black lives and struggles since the dawn of photography in the late 19th century.6 The exhibition included the works of early photographers like Battey, Addison Scurlock, The Goodridge Brothers, Harry Shepherd and Arthur Bedou, among several others.

As a Black person who calls Minnesota “home,” I was especially drawn to the work of Shepherd and John F. Glanton featured in the exhibition from the late 19th and early 20th century. Shepherd’s portrait Frederick (or Fredrick) L. McGhee (1861-1912), bears the mark of his studio and its address on Wabasha Street in St. Paul. His was the first Black-owned photography studio in the state. His subject in the portrait is Frederick McGhee, the first African American lawyer in Minnesota. McGhee worked with Du Bois as an organizer of the Niagara Movement, the progenitor of the NAACP.7

The murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May 2020 sparked a national racial reckoning. Our state, more readily known for our snowy weather, casseroles, and Nordic whiteness, became the epicenter of a righteous uprising in the name of Black lives. I remember people outside Minnesota noting how they had never thought much about there being Black people in the state. And yet, photographs taken by Shepherd, Glanton, and Chamblis, declare unequivocally: we been here. A grouping of Glanton’s photographs in the exhibition presented a set of black and white photos from the 1940s. A young woman sits on the floor smiling with vinyl records around her lap. There is joy, ease, and pleasure in her posture. In another, a group of men in suits prepare and groom each other for a wedding, perhaps. The men hold hands and they beam at each other—at themselves. The entire photograph captures an easy tenderness and the glory of this very quotidian brotherhood.

In a Black world, the past is not just prologue.

In the exhibition, Battey’s photographs of Douglass and Du Bois faced another gallery wall with photographs of more recent civil and racial justice protests and struggle. I stood in the space between the walls, taking in the images on either side of me. I could see the reflection of Douglass and Du Bois’s portraits as I looked at four haunting landscape photographs by Kris Graves. Each of Graves’s photographs center the physical locations where Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, Michael Brown, and Freddie Gray were killed by police. I was struck by how the past and present faced each other, engaged in conversations that feel far more complex and fraught than a neat linear narrative on the chronology of Black struggle and attempts to sanitize public memory. The reflections of Douglass and Du Bois followed me, as artist Vanessa Charlot captures a soft intimate moment between a masked couple during a Black Lives Matter sit-in in 2020. I spied Battey’s photographs again in the corner of the frame of Walter Griffin’s Civil Rights March, where Jesse Jackson leads a commemorative “Bloody Sunday” march in Selma, Alabama in 1990.

Black struggle is often evoked in relation to the collective, the community, “the culture.” Yet, the experience of the “one” is equally important. The individual in the collective, in the churning mass of righteous rage and outcry is captured in Nancy Musinguzi’s Son of Sons. The photograph centers a man and a baby. Community members can be seen behind them. The baby’s face is turned toward the storefront of Cup Foods, where only the day before George Floyd had been murdered by Minneapolis police officers. The man’s masked face is partially hidden behind the baby’s dark curls.

In Jon Henry’s Untitled #35, North Minneapolis, MN, a woman cradles a lifeless young boy representing the countless Black mothers grieving slain sons. The snow-covered ground around them seems to heighten the grief and desolation. In both Musinguzi and Henry’s work, the lens’s focus on the individual seems to quiet the noise, deepen the gravity of the tragedy and injustice. In both photographs, the artists also explore what happens next. What happens after the senseless killing and the deaths of Black men, women, and children? Who is left behind? A city, a community, a mother, a father, a child?

Photographs in Black communities are sacred, often adorning homemade altars where the photos of deceased loved ones and ancestors might sit. The exhibition was curated, the space designed with a labyrinthine quality that invited wandering, wondering, a contemplative roaming. Arriving at the heart of the labyrinth felt like arriving in an inner sanctum, a deep sanctuary—both homecoming and homegoing. There was a seating area with curated soundscapes for each artist’s work. The photographs in that area of the exhibition collectively felt like a cocoa-buttered laying on of hands, the tickle of church hat tulle, the scent of Florida Water, and the drum rhythms of orisha songs.

In Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II, artist Endia Bell photographed Barber before a backdrop of the North Carolina House of Representatives chamber. The backdrop fits almost seamlessly with the pews and stained glass of the Pullen Memorial Baptist Church framing it. Barber is a faith leader and social activist, and Bell’s connection between the church and the government chamber underscores how politics, activism, and the “work of the spirit” are intertwined in Black life. The idea of “Black consciousness” is most often discussed within the context of political awakening. Yet, I have always resonated with the deeply inner work, the soul work it takes to honor and protect your own sanctity as a Black person and to fight to ensure that it is protected in others. It is a spiritual journey, really holy work, to find self-determination, self-love, and community care in a world bent on your destruction.

Yet, still we fly.

In Consider the Sky and Sea by Ayana Jackson, a regal water spirit floats in the deep of the cosmos, an “aquatopia.”8 The kinetic blur of the spirit’s feather-fringed skirts grants the image a powerful magic. Working with mythology and speculative fiction of the African and African diasporic world, Jackson imagines new futures mined from a re-staging of the past. Jackson and several other photographers in the exhibition offer critical ethical considerations about the limits of photography and its historic role in reproducing racism.

The tendency when faced with such a large body of work by Black artists is to evoke the collective, the community. There’s an automatic thrust to speak of “Black life,” singular, in which this singular Black community collects and coheres. And so much of that is true, and perhaps, necessary. So much of that is about the ways in which being Black in this world has been shaped in response to anti-Blackness. Yet, to simply read Black artists and the history of Black photography as always only engaged in an oppositional or resistant practice is to fall short of the whole grand panorama of which Douglass spoke. Blackness is not just defined by an oppositional stance or gaze. Blackness is also about Black aliveness, and that aliveness is myriad.

A Picture Gallery of the Soul explored what it means for Black people to look back, and for Black photographers, and ultimately, everyday Black folks to pick up their cameras and participate in beholding and being beheld by kin. The photographs remind us of the poetry that grounds our lives and even our politics. They take us back to the proverbial waters to wade with ancestors who flew and swam because true freedom is a birthright. They center the “one” so we can better understand that fluid highway of Blackness from which we take flight and affirm our Black being.

A Picture Gallery of the Soul, curated by Howard Oransky and Herman J. Milligan, Jr., was on view at the Katherine E. Nash Gallery at the University of Minnesota from September 13-December 10, 2022. The exhibition catalog is available from University of California Press.