Does Art Need Words? Arts Writers on Arts Writing

As the culmination of their fellowship year, the first cohort of Mn Artists Arts Writing Fellows share a discussion on the practice and process of arts writing

The paranormal thing about writing is that I don’t believe we choose it; it chooses us. We get invited to be this vessel, this carrier of context, and we accept as it becomes a hauntingly innate part of us. Context. You stare at a screen long enough and the words manifest and disappear like apparitions. And sometimes you feel like an isolated alien stuck on a planet of your own design, and sometimes you feel a superiority complex when everything you write becomes quintessential truth, but with any hope it all balances out. Okay, maybe it’s not that dramatically demonic, but I’m writing this days before Halloween and I can’t help but feel a little possessed by the mystic season.

Though I’ve always considered myself a writer, labeling myself an artist has come with a multitude of contingencies—mostly imposter syndrome. Maybe that’s why I was so drawn to art and artists: they exuded what I couldn’t yet reach in my own practice. My arts writing practice began with Q&As in part because I didn’t feel confident in my ability to critique art, having no academic arts history, but grew into realizing the art of conversation was my sweet spot. I am, by nature, a conversationalist. It’s the connection element: listening to people talk about what they’re passionate about, what drives them, what inspires them, what disgusts them. It fuels my own natural curiosity. Whenever I feel stuck or trapped in my own mind, I interview an artist—even if their work doesn’t completely resonate with me—and feel this renewed sense of the world, like looking at it through new eyes, a fresh perspective to knock the cobwebs off of mine.

Earlier this fall, two of the three 2022-23 Mn Artists Arts Writing Fellows presented a live panel on the topic: Does art need words? I, being the third fellow, couldn’t be there in person to add my experience and process to the discussion, so what follows is an abridged and edited version of the talk, with added footnotes of what resonated with me, what felt different from my personal practice of arts writing, and reflections and ruminations.

—Juleana Enright

Christina SchmidArts writing is not a career that people seek out. It sits between scholarship and creative nonfiction, and has journalistic edges—or that’s really how some people understand it. Mining that space and navigating that terrain is part of today’s conversation. Nicole, how did you get started with art?

Nicole ASONG Nfonoyim-HaraI’ve always loved art and I’ve always loved engaging with it. I feel like no matter what art I am experiencing, it’s this moment of encounter. The writing is really about describing that and writing into that for me. It almost feels like I have to do it as a compulsion. And maybe that’s because I’m also a creative writer, and so when I engage with art I feel like I need to do that for myself. In terms of arts writing as a thing that I do in the world, I didn’t realize it was something that I could do. My first job in the arts world was at the Rochester Arts Center, working in the development department. There was a culture there where it almost felt like you couldn’t talk about art if you weren’t in the curatorial space working directly with artists.

JULEANA ENRIGHT: I resonate with this concept of writing as compulsion, and would say that not writing—being away from writing—can also feel like a hunger. And that work culture makes me think of the policing of agency, who is deemed part of the canon of arts engagement.

It wasn’t until I started working with some of the curators just as friends and talking about work that I realized I had ideas about art and wanted to be in conversations about them. I got my first official writing gig from a former artist who was at the Rochester Art Center who thought I had things to say and invited me into that world. That was almost 10 years ago, so it’s been really exciting to continue to do that and to continue to grow and learn. I feel so new as an arts writer and feel like I don’t know a lot, but I do know what I like to write about.

When I write from that space of encounter, my ideas touch up against my own world of meaning and then also the meaning worlds of art and the artists and the audiences out there. The fun part is when they diverge, when my meaning world and this meaning I’m making is different. That’s where that friction and conversation happens, which I think is really generative and exciting to me as someone who engages with art.

How about you?

CSYes, that moment of encounter certainly also plays a role in how I approach art. Fun fact: Nicole and I just discovered in talking about this conversation that each of us took exactly one class in art history in our entire educational careers. So that feeling of being an interloper, and of not really belonging, or—

JE: It is of note that I’ve also only taken one art history class and it was boring and stale. I remember I kept thinking, “Where are all of the queer and femme artists? Why aren’t they represented here?”

NANHLike being an imposter.

CSThat is something also very familiar to me. The way I fell into arts writing actually began in an auditorium—not all that different from this one—where a Norwegian artist, young, cute, charismatic, was talking to a crowd of mostly students. Everyone was completely enthralled by the work and by his words. I sat there with this growing sense of discomfort. And I couldn’t quite put my finger on what the source of that discomfort was. It actually took me a few days, and conversations with friends who were artists, to figure out where that discomfort came from.

Writing was really just an exercise for me to figure out and to get that thing that was rattling around in the back of my head on a piece of paper. I wrote it, and a friend of mine said, “You should publish this.” I sent it to Ann Klefstad, a former managing editor at Mn Artists, and she called me as soon as she got that email and said, “I want to publish this.” I think it went live the next day. I was like, “Oh, this is really cool.” I was paid for my writing for the first time, I think ever, because academics don’t get paid for their writing, not in that form anyway.

But I think more than actually getting that recognition, what really drew me after that experience was how many conversations I had with artists following that piece who said, “That was important that you said that, and that was really an interesting contribution to the conversation.” I realized that rather than writing as an academic and bringing the artwork to support my grand thesis and theories, I was much more interested in being in conversation with artists and being a kind of cultural first responder.

NANHAs you were talking, I was thinking about what keeps me doing it. I continue to do it for all the reasons that you stated, but then there’s also a sense too—particularly when artists get to read what I’ve written—of having felt seen. For me, having an anthropology background and a background as an ethnographer means it’s very important to be able to hold space for and represent the subject, it is in a way that the subject feels seen.

JE: I think about this element of “feeling seen” often after a piece goes live. Even if it never gets read—because often we have no idea if it has, or who the audience is—I still feel as though I’ve offered a piece of myself up for consumption. It’s vulnerable and exhilarating all at the same time.

Can you talk a little bit about one of the pieces that you’ve written over this fellowship period and how that may illustrate your process?

CSThere were a couple of things that I really wanted to do with this space and time that the fellowship afforded. I really wanted to connect what’s happening in the Twin Cities to work I see elsewhere. That kind of bridging of environments and connecting conversations that are happening locally, nationally, globally, was something I was interested in doing.

The first piece, “The Vampire Is A Virus Is Desire,” connected the conversations I was having during a summer in Europe and visiting amazing art. But then as the year progressed, I was immersing myself in all of the galleries, whether college or artist-run spaces, and seeing if I could spot a pattern, if there was a pulse. For me that was a really interesting exercise, to see if there was something that connected artists—even though they’re working in very different mediums and maybe don’t even know each other—if there were narratives, themes and tropes that could transcend the individual.

When you’re starting out, you don’t really know what you’re going to say. There’s just this very intuitive feeling that there’s something there. I think this is where the creative part of the practice comes in. We follow our hunches, and we wade in and see where the work will take us. That element of curiosity and exploration and seeing what kind of ideas the work will generate is something that I very much enjoy in the process.

JE: I think of it as “playful exploration.” Being in tune with the element of curiosity and open to whatever path it takes me down. But it can be terrifying at first. Like, “What am I trying to say? Why does it even matter that I’m saying it?” It comes down to self-trust and that could be the vessel aspect I was mentioning before.

Fidencio Fifield-Perez, dacament, 2016-present. Courtesy Night Club.

Joyce Lyon, Cooper’s Pond #1, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Form+Content Gallery.

Ruben Nusz, Frieze (for V.G.), 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Weinstein Hammons Gallery.

Gregory Rick, Uprising goddess, 2023. Courtesy HAIR + NAILS.

Groundwork, 2023. Courtesy Dreamsong.

JJ PEET, Buoy, 2023. Courtesy David Petersen Gallery.

NANHBased out of Rochester, I’m often asked to do a lot of writing about things that are happening in the Twin Cities, so my goal was to get a bit more of a pulse on what was happening in Rochester and the wider southeast Minnesota area.

In terms of my art writing, I’ve been asked to maybe write about a specific exhibition or specific artists, a catalog essay, things like that. This fellowship was this really open invitation to be like, “What do I like to look at? What do I like to experience? What interests me? And what is my voice?”

One of my favorite pieces to write was “We Fly: On Black Aliveness in A Picture Gallery of the Soul,” which was right here in the Nash Gallery. It was sort of a transformative experience, and one of the first times that I was writing about an exhibition at that scale, where there were so many different artists and pieces. It was spanning decades, a century of time. It was a time where I wasn’t talking to anyone that was directly involved with the gallery or the exhibition. I wasn’t talking to the curators, the artists, and it was just me unfiltered in this experience of the exhibition.

It was a challenge for me as a writer, but also one that I nestled myself into and really enjoyed that process of thinking through: “What are the pieces I’m going to write with? What are the things that spoke to me? How do I trust my looking and my voice when I haven’t talked to anyone about this in the work I’ve seen, and now I’m expected to write about it?” It was a challenge, an exploration and this very beautiful process that really taught me other things about my voice that I might not otherwise have had the opportunity to.

CSThat piece, for me, was really revelatory reading because it had, on the one hand, a very strong personal presence, and it was also bristling with ideas and had an amazing attention to the detail of the work—the sheer breadth of tackling this exhibition.

Juleana took a very different approach this year, and most of the pieces were conversations with artists. In re-reading them in preparation for today’s conversation, I was really struck by their skill as an interviewer. And bringing books that I still need to read, for instance, Glitch Feminism, in their conversation with Skawennati. I was like, “Oh my god, the ideas here are so rich.”

That’s so different from what I do. I appreciate doing a studio visit. I appreciate hearing a curator explain the curatorial narrative of an exhibition, but ultimately, as you were talking about earlier, it’s the meaning we make in the encounter with the work, the ideas it generates and where it takes us. Juleana’s work and writing really made me appreciate having space and platform to hear from the artist. Personally, I don’t think that artists can always define or confine what their work means. It always will exceed the intentions of the maker.

Part of what I do as a writer is to engage with the artwork and see the intent. But then there’s also context; there’s audience. The work keeps changing as it moves through the world. That movement is what I am primarily interested in. I appreciated just seeing the difference in these approaches to working with artists and writing with art, not about art, but really with art, a dialogue with art.

NANHI do think one of the gifts of the fellowship was being able to see all the different ways in which we experience art and talk about it. Juleana’s work is such a perfect example of what it means to allow artists to speak more about themselves. That format really does allow for it in really lovely ways. On a logistical level, I was always like, “How did this get done?” I’m terrible at editing, and so it was always so crisp, but so profound and there was sort of this lightness to the work. It was so steeped in meaning and gave so much voice and space to the artists as they were engaging in the questions. The questions were always on point, so I always appreciated that.

JE: The strange thing is I feel hyper-aware of how my writing practice varies from other people’s, including Christina and Nicole’s. It can feel very intimidating at times, like “Oh, am I doing it the wrong way?” But as Nicole said, it’s the different ways in which we experience and process art, which can never be wrong. My way is to understand it from the place of the artist and then envision it for myself, dig deeper or challenge through the questions I ask. My personal reflections on the art are embodied in the questions. And I’m currently thinking, “How will this get done?” as I edit only page six of 20 pages. Navigating editing conversations is truly challenging because how do you preserve or represent the feel of an in-person dialogue? The inflection, the emotion, the comfort or discomfort, as is sometimes the case.

I don’t think we’d ever met in person, but your (Christina’s) work was some of the earliest arts writing I read, because I was introduced to arts writing through my work here in Minnesota. There’s this invitation to rove and jump scale between your personal intimate reflections around things, and then also to this level of the wider context, and the wider implications of an object or an artist’s work or an exhibition. That’s the type of writing that I love to read, whether it’s arts writing or not.

Cecilia Cornejo Sotelo, The Wandering House, 2019. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Arya Misra.

Cecilia Cornejo Sotelo, The Wandering House, 2019. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Sergio Demara

Cecilia Cornejo Sotelo, The Wandering House, 2022. Courtesy the artist and Rochester Art Center.

Cecilia Cornejo Sotelo, The Wandering House, 2019. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Arya Misra.

Embroidery activity for H O M E ~ exploring, mending, reimagining, 2022. Courtesy the artist and Rochester Art Center.

CSIt’s also interesting, though, to realize how many clichés there are still out there, lingering clichés, about art critics—from the poison pen, to the heroic air guitarist who presses language to the point of fracture. We thought it might be interesting as we acknowledge what we value in each other’s practices, to think about the different genres of arts writing. Arts writing is pretty amorphous and can go into many different directions. In my practice, some of the work I do for national publications, you get 250-300 words so there’s really not much room for anything but, “This is what’s on view and this is why I think this is noteworthy.” And you’re done.

Do you want to elaborate on the different voices that these different tracks of arts writing allow to emerge?

NANHThat’s an excellent question. I’ve done catalog essays for the Jerome fellows twice now. They were different because we also did studio visits with them. A lot of it was about being able to engage with the artist, with their practice and their work. Because of the timeline of those essays, we were writing more generally about their body of work to date. I have a friend who recently said that in a way, sometimes we become artist biographers. With those exhibition catalog essays or pieces engaging with the artist directly, I feel very much an ethos of responsibility to ensure that the artist feels a sense of being seen.

JE: I resonate with this, being asked to do the catalog essay for MCAD’s thesis grads. There was so much to cover and elaborate on since you were talking about someone’s very personal final work, yet only so much space and word count to work within. Being concise is always a problem I have. As Emily can attest to, my word counts are nearly always over.

I think that comes from a lot of my own personal ideas around justice and what that looks like. But then also as an anthropologist, as an ethnographer, ideally there should be this kind of care laid in solidarity with whoever you are “representing” or writing about.

JE: Totally feel this, and it’s one of the hardest parts for me about being a local arts writer: knowing and being in relationship with Twin Cities-based artists and art spaces, and feeling a kinship and responsibility to accurately reflect them and their work.

I think sometimes I bristle at being a critic because—who am I to be a critic of anything? I’m called to be critical and I’m called to ensure that I have my certain sense of what I’m experiencing, what I’m seeing, the artists and the work is there, the audience that is there as well. I’m there to provide a space holding for all of those relationships and all of those new worlds in a way that is accessible.

JE: Vessel for accessible art consumption while also holding space for personal reflection—delicate balance to strike.

Skawennati, Three Sisters: Regeneration, 2022. Image courtesy the artist.

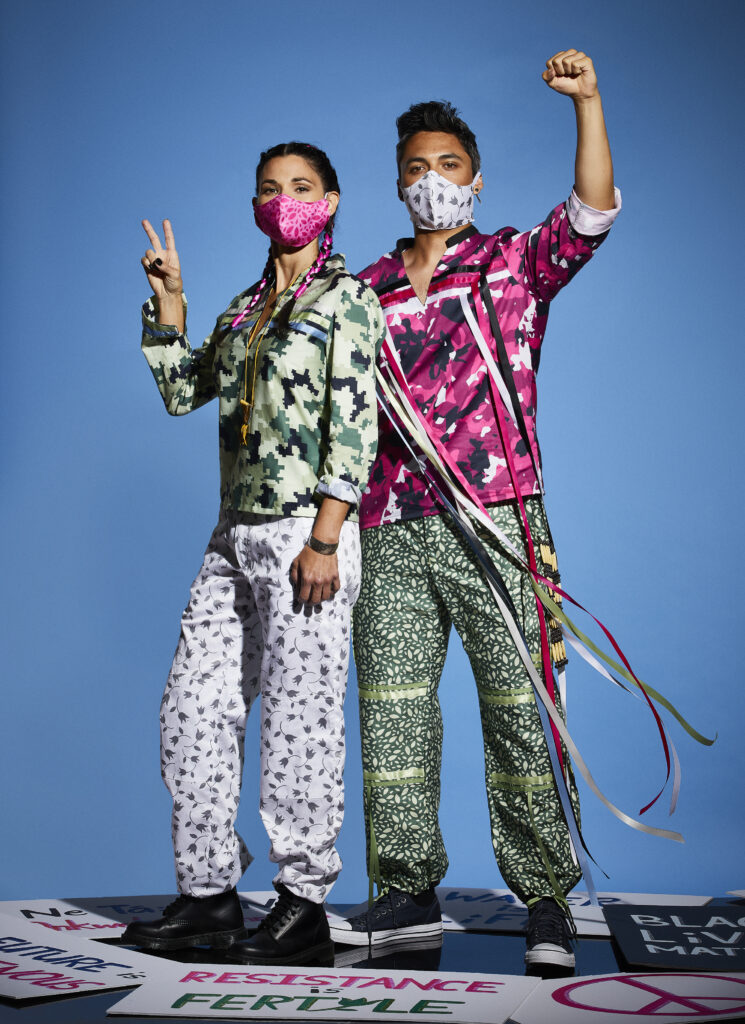

Skawennati, Calico & Camouflage IRL, 2020. Photo: Daniel Cianfarra.

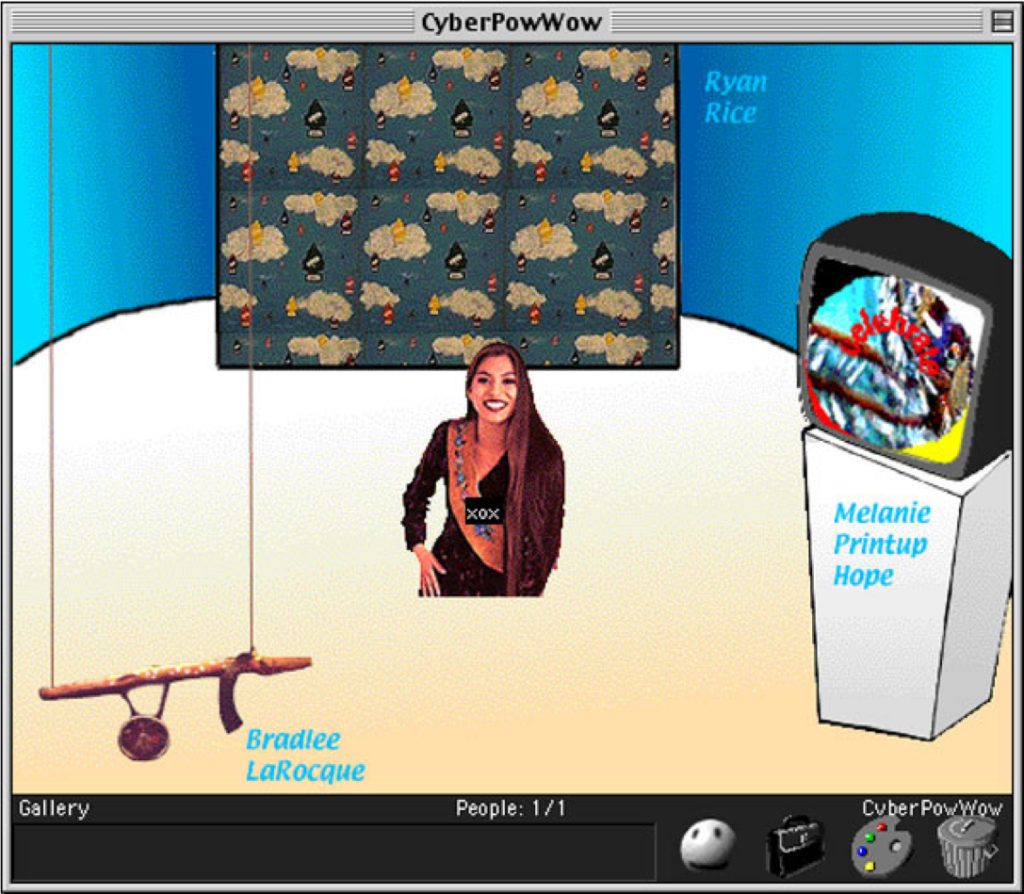

Skawennati, CyberPowWow, 1999. Featuring Skawennati’s avatar, xox, and the work of Ryan Rice, Bradlee LaRocque, and Melanie Printup Hope. Image courtesy the artist.

Skawennati, Dancing with Myself, 2015. Photo courtesy the artist.

Skawennati, Family in the Sky from The Peacemaker Returns, 2017. Image courtesy the artist.

Skawennati, Intergalactic Empowerment Wampum Belt (Xenomorph, Onkwehón:we, Na’vi, Twi’lek, E.T.), 2019. Image courtesy the artist.

CSOne of the words you used when you talked about your practice that really landed for me was witnessing—holding, reflecting, witnessing, noticing. One way of understanding critique is that I pay really close attention. That’s something that we bring, a practice of visual literacy and really looking at details. The poet Maggie Smith said, “Critique is an investigation of possibility.” In that sense, I can absolutely embrace the critical thing. I’m less interested in judgment and arrogant power display.

I’ve worked with artists and contributed essays to artist books where the artist is really curious what I’ll do with the work and where it will lead me. Those open-ended explorations are a pleasure and a privilege. On the other hand, I have found myself in artists’ studios who basically have said, “This is what I want you to write.” And I’m like, “No, I’m sorry. This is not how I work.”

That idea of haptic criticism really resonated for me. I’ve also found a lot of resonance in Julietta Singh’s work. She talks about vulnerable reading—whether you read a text, whether you read a work of art—that you are vulnerable too. You are open to letting the artwork act on you. In the act of writing, I open my mind, what I’m thinking, my associations, to where the work takes me. There’s an excruciating vulnerability in being an arts writer and having the inner workings of your mind out for the world to read.

JE: Agreed. See my comment above.

And then, of course, writing in a community of this size, I know some of the people whose work I’m writing about. It’s my personal ethos that I can’t say anything in print that I wouldn’t say to this person’s face. We’re already talking about this dialogue with artists, and certainly artists are part of our audience. So my next question is: who is arts writing for and what does it do?

NANHI’m always asking myself the question: who is reading this? Who gets to read this? Do they also feel seen in this mediation of relationships, and these encounters in the work? I feel like there might be a straight up answer, which is when we’re asked to write for an exhibition catalog, the audience is people who are coming to see the exhibition. Sometimes we’re asked to do things, and maybe the platform or the publisher or the museum, the gallery, whatever, has an idea of what that audience is, but for me, it’s messier because there’s so many spheres within the art world, and then who’s looking.

Sometimes I wonder too, who is actually reading the exhibition catalog? Does everybody read the exhibition catalogs when they’re going in to see the work? Do people appreciate that? I have more questions about it than anything else. So much of my arts writing, when I get to the blank document and I’m starting to write, I don’t think I’m writing to someone out there. I’m still in that space of writing about my encounter and that feeling of what that experience was like for me. It really isn’t until the end of it, when I’ve told the story, and I’ve exhausted, spilled out my brain around all the things, that I can then be like, “Okay, who might this be for?” Of course, as I said before, I think the artist is always in my mind, especially if I’ve engaged with them directly.

In terms of the audience, I would want someone who hasn’t been to the exhibition or hasn’t seen the work directly to be able to engage with it. I’ve done a lot of post-exhibition reflections, and I want there to be a feeling that the work has meaning, and the space that it created has meaning outside of the exhibition. People can continue to engage with it through my work, after that little space of time when things were up and people were engaging with it. I’m not sure if I’ve achieved it yet, but it’s something that’s an aspiration of my work. I want to continue to be part of the lifeworld of the art objects beyond the world of the exhibition.

JE: I think that’s another challenging aspect of post-exhibition reflections for me, finding a way to have the work mean something and continue to engage past the exhibition run, past the excitement of an opening reception.

CSI’ve talked to artists who say, “Well, the exhibition goes down and what remains is some installation photos. The artwork in the studio is packed up, but what remains out in the world are the words.” So, this way of leaving a trace, of creating an archive, that’s part of who I write for. Of course, I also write for myself figuring something out, when something does not stop nagging at me. Then the process is: “I don’t know yet what I’m going to say, but I’m going to sit down.” Sometimes that is pleasurable, and sometimes it’s really fun to sit down and the writing just flows. Other times it’s like pulling teeth, and it’s only the deadline that keeps you going—but that pressure can be very generative as well.

I really write for anyone who wants to do more than look at artwork, who is interested in actually digging in and looking—and maybe, having been moved by the work, wanting to understand more about that, hearing the artist’s words, attending an artist’s talk. It’s for anyone who wants to see how someone else grapples with the work and makes meaning with the work, without any claim to this being the one and only right way to engage with the artwork—I don’t believe there is such a thing—but to lean into that subjective process of meaning-making, and to really empower people to do that. I wish we all did much more of that. That’s part of who I think about when I think about audiences, both artists and non-artists, to open up the work.

JE: Yes! This! And going back to what Christina commented about the reference text I sometimes pull into my writing, it’s those people I write for. Those who are going to take to the time to fall down the rabbit hole with me. It’s like a choose-your-own-adventure of how much to you really want to absorb, reflect, explore.

When I go the studio visit route, what I really want to find out is: what keeps them making this work? I want to understand this edge of what fascinates them in their work and what intrigues them, because that also fuels my excitement and my curiosity then in writing about the work and in activating the work on the page. It’s this mysterious life that you were talking about.

The live conversation continued from here, incorporating dialogue with the audience: many of them artists, arts writers, curators, educators, and students themselves. We’ve chosen to document some of the questions, paraphrased and unanswered, in order to spark your own thoughts.

- How does arts writing interact with the arts market? What is the economy of arts writing itself? How can arts writing add value to the field?

- How do you account for or attend to your own bias? How do you hold your writing accountable? How does the choice of what to write about reflect your own biases, and what does it mean for the writing to put them on full view?

- How can language be used to promote gatekeeping and exclusion, or greater accessibility? How can arts writing allow broader audiences to connect to artwork?

- Have the stakes of arts writing shifted as the ecosystem of arts writing platforms has changed? Does your voice feel louder as the number of publications has shrunk?

- How can arts writing bridge the intensely political and the intimately personal?

- Where does arts writing sit in terms of genre? How is it related to, and distinct from, scholarship, journalism, and creative nonfiction?

- Does art need words? What does art need, and what do we need? Don’t we need companionship, conversation, and community?

I keep reflecting on the title of this panel—do words need art? My final thought is that I am in this reciprocal and codependent relationship with art. I need it just as much as it needs the critical, subjective, or objective lens that we as arts writers provide. And while art would still exist if no one was writing about it—much like a tree in the forest would still make noise if no one was around to hear it—arts writers wouldn’t exist if there wasn’t art to sustain our mysterious journey of exploration, a sustenance. Like a compulsion, we continue to feed on its beauty, its disruption, its ugliness, its provocation. The haunting of an object through words.

—Juleana Enright

“Does Art Need Words? Arts Writers on Arts Writing” took place on October 4, 2023, at the Regis Center for Art and was co-presented by the Walker Art Center and University of Minnesota Department of Art, via the Visiting Artists & Critics Program. >> more information

Find more information on the Arts Writing Fellowship, and read the full series of pieces by the first cohort of fellows, on Mn Artists. >> more information