We Are All Complicit in Craft: A Conversation with Josina Manu Maltzman

Two friends talk genre, writing as a tool for liberation, and living out ideals

Palestine demands that all of us, as writers and artists, consider ourselves in principled solidarity with the long cultural Intifada that is built alongside and in collaboration with the material Intifada. We are writing amidst its long middle; the page is a weapon.

––Fargo Tbakhi, “Notes on Craft: Writing in the Hour of Genocide”

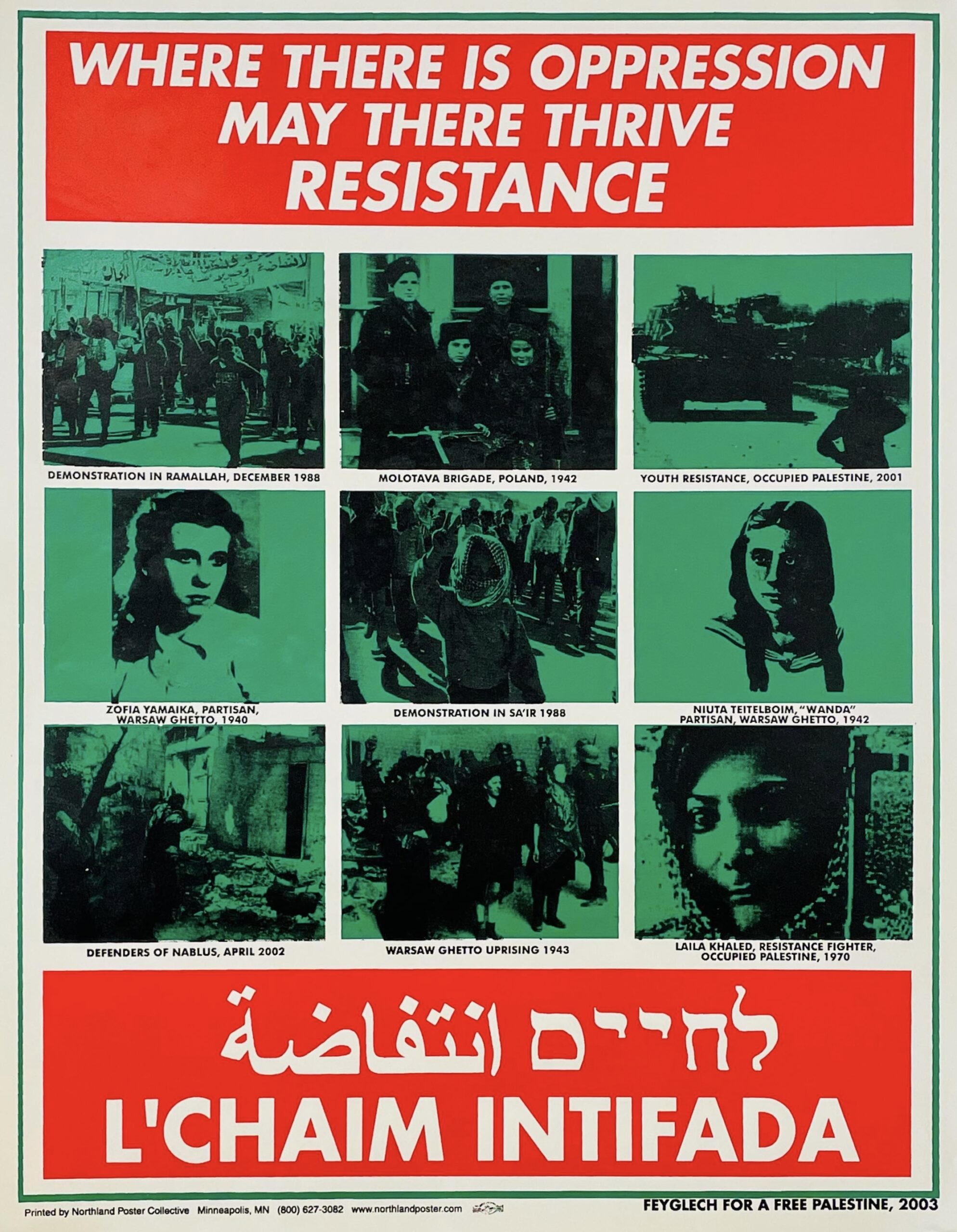

There’s a striking poster in the hallway to the left of my bedroom door. In sharply architectured reds and greens, the poster depicts images of Jewish partisans who fought against Nazis alongside images of Palestinian fighters resisting Zionism. Emblazoned at the top are the words: “Where There Is Oppression May There Thrive Resistance” and at the bottom: “L’Chaim Intifada” (Long Live the Intifada) in Yiddish/Hebrew and Arabic, as well as its English transliteration. In the corner the screenprint is attributed to “Feygelech for a Free Palestine, 2003.”1

As gays are wont to do, I learned more about the poster outside of my home, still in my neighborhood, catching up over bubbly waters at a friend’s house… My friend also featured the poster prominently on their wall, and disrupted my experience of its quotidian presence in my life when they mentioned, “You know your housemate made that, right?”

I did not–and returned home in search of Story, which is to say, Connection.

Relationships are the most potent space of intersection for my creative practice as a writer, not to mention my commitments as an activist and organizer. Writers and artists across a diversity of social movements have espoused the idea that our revolutionary potential lies in our intimate and daily relationships, telling us we need to live out the imaginary vision that our art seeks to describe.

Josina Manu Maltzman is a carpenter, writer, rabble-rouser, and my beloved housemate. Their work builds connection in the truest sense of the word–bridging materials, communities, and conversations to remind us that it’s worth it to not give up on ourselves and each other. As a memoirist, Manu Maltzman plays the fool in their work, which portends an unsettling provocation for the reader. Similarly, their cultural work jars open new worlds to connect individual recognition with outward political action. Manu Maltzman is a white, anti-Zionist Jewish person coming from a Zionist family. They exercise personal narrative and relational intimacy as tools for building community power towards the liberation of Palestine and abolition here at home. For Manu Maltzman, what happens on the page, on the Zoom screen, and in the public reading, is an active, non-placative space of engendering relationships. Within relationships, liberatory change is anchored in collective responsibility and, importantly, care.

Our conversation–likely over bubbly waters–took place in the spring of and summer of 2024.

A few details:

- Manu Maltzman and I collaborate as organizers for the abolition of police and carceral systems with the abolitionist project Relationships Evolving Possibilities (REP).

- At the time of publication of this piece, the death toll in Gaza is estimated at over 39,000, with the total deaths attributed to the war around 186,000, along with an increase in violence against Palestinians in the West Bank. Manu Maltzman responded to the urgent call from the International Solidarity Movement for volunteers to witness and document settler colonialism’s abuses in Palestine’s West Bank by going to Masafer Yatta in May 2024.

- As writers, Manu Maltzman and I truck in generic forms with mass cultural appeal: memoir and speculative fiction, respectively. While our modes of engagement with each genre are unique (biomythography and science-fantasy/horror), the demarcations of our intended forms are ultimately laid out by capitalism–which collapses aesthetic choices, reach, and readership into market value.

In our exchange we circle writing as a tool of liberation through our long-arching commitments. As writers, we build our skills and negotiate our own agency within inherited histories of aesthetic choices, form, and the publishing market. As organizers, we contend with our responsibility to invoke our readership towards witness and agitation. We prepared for this conversation by reading Fargo Tbakhi’s essay “Notes on Craft: Writing in the Hour of Genocide,” quoted in the epigraph of this piece, which both moved and inspired us to remember the page is a weapon as we negotiate a balance of craft and political thought.

Josina Manu MaltzmanWhen I sit down to write to be read, I have an agenda. I write memoir, specifically biomythography.

Aegor RayThose are both genres I think of as so tied to women, and specifically with biomythography, with Black women, working class women, and women of color. When you think about the people who would read your book, are you thinking, are they women? Are they workers? How do you see people holding your book or receiving it?

JMMI love that you immediately think of memoir in the terrain of women of color. Yes! That’s why I always shout out Audre Lorde and her coining of the phrase “biomythography” to describe her work. For a trade memoir right now, it’s white women, white women, white women. White women really dominate the New York Times bestseller memoirs. I think it’s important to return to the roots of the genre. Against The Grain is a work I’m trying to get published right now, and it’s about being a carpenter in the trades for 20 years. It’s a memoir that uses work and labor to talk about how the structures of patriarchy, white supremacy, and racial capitalism compete against each other and prop each other up in the workplace. I want to talk about that structure. I’m using my journey of work to have that conversation and to share my story as a contribution to the dialogue. But I’m doing it in a way where the dialogue is snappy, energetic. There’s a lot of characters. The action’s moving quickly. I want it to be the kind of book that someone takes on vacation and reads in a weekend and continues thinking about for months to years to come, and is passing along to their friends to take on their vacation.

What do those people look like? Definitely anyone who’s had a job. Anyone who is affected by patriarchy, white supremacy, and racial capitalism. Anyone who thinks that they haven’t been because they’re white–they especially need a close read. I use myself as the fool in the narrative, and that’s the hook. I want to catch the cheek of some white people that need to be brought in, talked to, and see themselves in the story. But it’s not just for them because that’s just way too narrow.

ARWhen people talk about writing as a tool of liberation from an explicitly politically-anchored point, I tend to imagine it as “the manifesto,” the political “toolkit.” It’s non-narrative, it’s didactic. And so I’m really compelled by your sense of staying with the reader through catchy narrative strategy, and the slow process of acknowledgement, and self-recognition.

For me, genre fiction has a similar effect. I actually hated horror growing up, and couldn’t stomach it. I was drawn to it after my father died–in my grief, it struck a chord. And through gender transition, other forms of genre like science fiction and fantasy opened up. I’m also interested in the challenges of these genres that feel propped up by racial capitalism. For example, it’s an exciting challenge to write horror that isn’t conservative, because it’s so often based on fear of the other as the unknown.

I see a relationship between our forms, especially in the implicit and explicit agreements that the writer makes with the reader. The reader is coming to be entertained, and I’d like to deliver on that. But if a deeper process of recognition can be provoked–something molecular and affective, where they’re not being preached at–I believe that’s where real change can happen.

JMMI don’t think people are stupid. I think that we can read complex thoughts and have hard conversations about complex issues, but if I want workers to be able to read this book–people with kids, people with commitments–I don’t see my writing as successful if I’m filling up a piece with data or constructing sentences that require multiple reads to decipher.

I think of some of the The New Yorker magazine short stories that I had to read in my MFA program, only listed by one instructor who is an older straight white guy. I felt like, “Why are we reading this shit?” Even when it’s abstract or absurd, it is reinforcing an understanding of our center being Capitalists. It’s so self-referential that it reinforces the structure that we’re living in. I’m also thinking about what you said about relating to nonfiction writers. You can’t make up how up fucked up and absurd our world is. There’s just no reason to try. At the same time, there’s a lot of space in non-fiction to tinker with “the truth,” in the curating of scenes and how they are juxtaposed, and through which perspective the story is told for example.

Where do you see your genre commitments as connected to your movement work? Are they connected?

ARVery connected. I am an Indian immigrant, and a trans person with sex-working experience who organizes for the decriminalization of sex work. I believe that people who have been deeply structurally marginalized can become, in a sense, larger than life. Literally in the 1800s, people would describe sex workers as the gutters of society. And the xenophobic, homophobic, and transphobic imaginary has definitely already constructed me, and the people I love most deeply, as monsters.

For horror specifically, I’m reflecting on the words of Mariana Enriquez, an Argentinian writer who named that she uses horror as a language because it’s the only appropriate approximation of the real horror she experienced as a child during the Argentinian dictatorship. Enriquez’s interview on Between the Covers really made something click for me–it is actually dehumanizing for people who have experienced state violence to detail what has happened to them in order to be heard. And then to wait to be received. That’s litigation. I find a lot of freedom and agency in, instead, making aesthetic choices that can potentially provoke an intense visceral response for the reader, and then bring them deeper into the heart of what I’m saying.

JMMThe expectation of memoir is that the writer, the protagonist, is supposed to come to a transformation. My idea of transformation in my memoir about working in the trades is thematic, not individual. I’m considering: What does meaningful work look like when your community is facing police violence? When your community is dying in an epidemic of suicides? What is the work when we go to get our paychecks so that we can survive, and yet we have to fight for our survival both at work and outside of it? What is the meaning of labor and where do we find ourselves in it? That’s the journey my character undergoes.

“Craft” first came to me as a word when I was applying for grants, trying to get into the institution, trying to get into a school for my MFA. That’s where the word craft came into my lexicon as a writer. But the way I always perceived it or thought about it was akin to carpentry. How I learn writing as a craft is how I learn carpentry as a trade. It’s in my workmanship, practicing with my nose to the grind, in all of the tools that I accumulate–all of that together is craft for me. In reading Tbakhi’s essay, my mind was just like blown apart because it’s clear that Craft with a capital “C” is the institutionalized molding of how we’re directed towards a certain kind of achievement in writing, and directed away from other kinds of achievement.

ARI’m really over jadedness as an affect for artists. I actually feel like my ideals, that I know we share, that art can change the world, allows me to then be realistic about the ways that I am implicated in the art world as a worker, which is separate but intrinsically involved with the practice of making art.

I’m thinking about the poet Rasha Abdulhadi, who has taken the dreaded artist practice of making a bio into a space of provocation and resistance. Her act is a reminder to take every opportunity where I’m given space to say the thing that I believe in. But the institutionalization of art can numb you to the access and autonomy you are given all the time.

JMMYes! Her doing that totally inspired me to do the same.

I hold that art can change the world and art must change the world. For me, art and writing are the sharpest weapons we have.

ARDid your relationship to writing and craft change while you were in Palestine?

ARDefinitely. I felt like my only role was to witness, to be responding. As a witness you feel so powerless, but also like you’re a part of a collective. It’s embodied and it’s not. The sense of powerlessness is so strong, and you have to return to your own senses. You’re experiencing things for other people, like a conduit, and it really displaces your own ego in writing. You’re crafting words in order for other people to viscerally understand the reality of occupation.

JMMDefinitely. I felt like my only role was to witness, to be responding. As a witness you feel so powerless, but also like you’re a part of a collective. It’s embodied and it’s not. The sense of powerlessness is so strong, and you have to return to your own senses. You’re experiencing things for other people, like a conduit, and it really displaces your own ego in writing. You’re crafting words in order for other people to viscerally understand the reality of occupation.

ARCan you tell me the story about the poster that you made?

JMMI went to Palestine in April of 2002. I was about to turn 29. I had come up in a Zionist environment and, at the time, I believed that my own personal criticisms of Zionism were enough to tell me what going to Palestine would be like. I was very naive and had a lot of learning to do. Personally, I’d spent a lot of time learning about Jewish resistance to Nazis. I was interested in narratives that held that Jewish people were not going like lambs to the slaughter. I was fascinated with how people engage in resistance. So I went to Palestine and I was there during Operation Defensive Shield, during the Second Intifada. It was a war zone in Bethlehem and I came back after two weeks and was like, “this shit has to stop.” Israel has to stop. I need to do anything I can. There is air in my lungs only to scream “NO!”

I did speaking engagements and report-backs and a year later, my housemate and I put together a big event and fundraiser for the West Bank. I knew I wanted to make posters. The image came to me of Jewish partisans fighting Nazi hell, interspersed with Palestinian fighters fighting Zionist hell. In all kinds of disparate and different ways–all of the events in the images use different tactics. Some were doing nonviolent protest, some were bombing train lines, some were hijacking airplanes, some were fighting back on their own turf, some were going into the enemy’s lines.

I’d been studying Yiddish and the phrase “Where there is oppression, may there thrive resistance” came to me in the form of traditional Yiddish blessings. That rhetorical move–where there is/may there –is very Yiddish. I know that Palestinians don’t need me to bless their revolution, but the framing was my own gesture of invoking my history and spiritual tradition with the overarching tradition of resistance against fascism.

As for L’chaim Intifada, it was really important to me to have this reflected in different languages. I hadn’t seen that statement before–now it has taken off, and I am so excited about that. I wanted to credit this poster to a movement, because that’s really how I saw it–ingrained in movements–so I created the organization Feygelech for a Free Palestine. Anyone can join this movement. It was to show that the creation of this poster is not acting as a singular person, it’s connected to revolutionary action over time. And that we can create what we need when we need it.

Josina Manu Maltzman is holding a talkback from their time in Masafer Yatta at Moon Palace Books on Wednesday, August 7, at 6 PM. Registration and masks are required. → Register here

Josina Manu Maltzman (all pronouns) is a writer, carpenter, and rabble rouser who believes we all have a role to play in ending genocide and settler colonialism. Acting from the belief that it is the obligation of people with privileges to do the work of dismantling systems of oppression, Josina finds that doing so is a spiritual act as well as revolutionary one. For more about Josina’s writing and how it is informed by being in the trades for over twenty years and their organizing work as an anti-Zionist Jew, visit their website.