The Vampire Is a Virus Is Desire: The Dark Blue and Other Posthuman Encounters

On contagion, surrender, and compromised thresholds—from Northeast Minneapolis to the Venice Biennale

Vampires are versatile.

From fanged folkloric monsters who abhor garlic, to historic figures such as Vlad the Impaler and Elizabeth Báthory whose cruelties are legend, vampires have long played a special role in the popular imagination. In 1819, John Polidori penned “The Vampyre,” a short tale that is generally considered the first modern vampire story and was born in the opium-fueled haze surrounding Lord Byron, Percy and Mary Shelley. Ever since, vampires have conjured contagion, seduction, and compromised thresholds. Rich intellectual metaphors have drawn on the figure’s strange propensities: Jalal Toufic compared the withdrawal of tradition in the wake of a surpassing disaster to a vampire standing right next you in front of a mirror—you know it’s there, surely, and still you can see no reflection. Gothic shlock, Hollywood blockbusters, and indie masterpieces—Jim Jarmusch’s Only Lovers Left Alive is so disturbingly romantic it makes your teeth hurt—have done their share to immortalize the undead. What does it mean to engage this storied figure in the maybe-waning days of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Not exactly alive, the vampire procreates and mutates and spreads much like a virus. The vampire promises eternal life in an echo of some religious faiths and simultaneously threatens with mortal danger. Its profound ambivalence propels its allure. Not born, the vampire is made by infection: the ultimate posthuman, it is driven by a hunger that displaces all other urges.1 This hunger lives beyond reason, consumes and takes over what once was a person, like malware or a depersonalized desire ready to annihilate everything in its path: it is “foreign to her will” and “forces itself irresistibly upon her from without.”2 These words actually describe not the vampiric hunger, but hail from Anne Carson’s Eros the Bittersweet.

Eros, as the ancients understood it, was a gift from the gods, and a double-edged gift at that: “neither the inhabitant nor ally of the desirer,” desire was a force to be reckoned with. “Love’s amorality is proverbial. It torments you and makes a fool of you and leads you to crime. It’s a god, not your best friend.”3 Ancient and archetypal, a force that emerges far from the light of reason and turns life upside down, desire-as-vampire remakes death into something transformative, something undead. The vampire is abject: formerly human, it is a source of both fascination and repulsion. It feeds on bodies and enters bloodstreams, all while compromising the boundary between life and death. The vampire is a virus is desire.

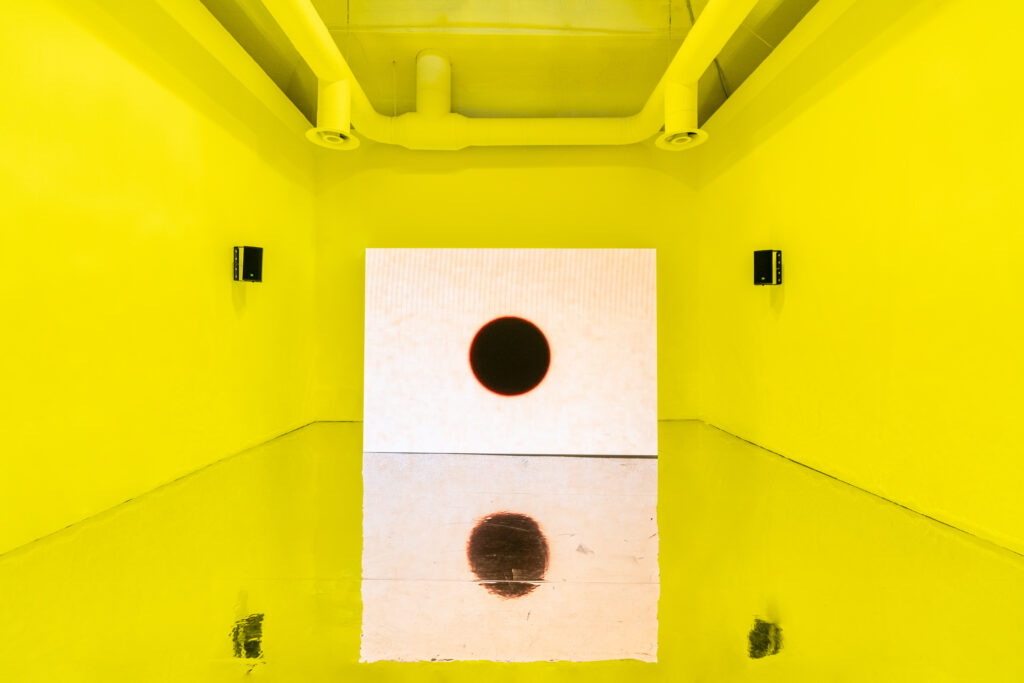

The Dark Blue, a group exhibition on view at the Rogue Buddha, explores vampirism today in the first show since the gallery reopened its doors post-pandemic. Named for a melancholy hue, the color suggests the blue of distance, characterized by its “uncanny relationship to absence, desire and distance,”4 as Anne Carson so memorably put it. It brings to mind the blue hour of dawn and dusk, the time a French proverb calls entre chien et loup, between dog and wolf. It is “the hour in which—and it is a space rather than a time—every being becomes its own shadow, and thus something other than himself. The hour of metamorphoses, when people half hope, half fear that a dog will become a wolf,” writes Jean Genet, gay godfather of outcasts and nomads.5 This time is the space of the dark blue, when the vampire stirs and wakes to embrace the cool of night; or, in the blue morning, flees from the rising sun.

The moment of encounter with the posthuman makes up the most compelling work in The Dark Blue. Of course, the show also features sexy vampires and witchy vampires, complete with black lace and boobs and bat wings and fangs, all standard vampire fare that, for some, never gets old. But most compelling to me are the moments of surrender, of yielding, of consenting to lose one self in order to become something not yet known: perhaps no “self” at all but a creature undone and dissembled, still connected to the other-than-human in ways we can barely fathom.

Caitlin Karolczak’s Nightmare (2014) stages an encounter with the vampiric: undressed and aroused, a slender young white man lies on his back, while a female form towers over him, shrouded in translucent fabric, her dark mane billowing around a pale face. Like her gauzy cape, her torso too is transparent, revealing bones and guts but no skin. An invisible arm extends over his groin, veiled, there and not there. The vampire’s wide-open eyes stare past his reclining body, as if he, like her, was there and not there at the same time: to her, he appears present not as a person but as prey, a mere means to fulfill her craving. His gaze, too, is rapturous, not at all focused on her eerie beauty or the danger she represents but absorbed by some inner reverie. Their encounter, though clearly also sexual, is not intimate in the sense of fostering erotic connection, but transactional, driven by entirely different sets of needs. Seduction, surrender, and a compulsive hunger fuel the scene.

In Rachel Coyne’s Untitled (2021), a bright red angelic figure swoops down and envelops a human figure in what looks like a consoling embrace. Reminiscent of the tarot’s Tower card, the image features a giant eye opening in the sky. This eye, though, sheds tears that hold crucifixes. In a nod to Christian iconography, a dark angel, her body dotted by distant stars, is falling into a purple void. The work makes visible the affinity between Christian beliefs and vampire lore: drinking non-human blood symbolizes union with the divine and promises eternal life. The crucifix holds sway in both worlds, symbolizing selfless sacrifice in one context while serving as the ultimate banishing tool in the other. In Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula, an unforgettable Gary Oldman rises from his coffin, hissing and spitting at his self-righteous pursuers who wield—what else?—nothing but a crucifix.

In The Dark Blue, there are no hunters. The show is an unadulterated ode to the vampiric dark. But this absence is not entirely fortunate. The hunter in vampire movies is never as alluring as their prey. The hunters’ cruelty is somehow legitimized by their defense of humanity. But another question lurks in the shadow of the hunter’s self-righteous retaliation: is it the very capacity for cruelty that produces the human? P. Staff, in their recent work On Venus (2019), on view at this year’s Venice Biennale, suggests as much: warped slaughterhouse footage “depicts states of violence that underpin the making of a human subject,” contrasting the horrors of industrially violated bodies with an imaginary life on Venus, “a sibling to Earth but one described as a state of non-life or near-death, a queer state of being that is volatile and in constant metamorphosis.”6 The human is made in an orgy of violence, othering all that is non-human but, in the context of vampiric, especially that which threatens to cast the human into a state of “non-life or near-death.” Yet the threat of thus coming undone, of ceasing subjecthood and becoming not exactly an object but abject, in-between, turns the vampire a cipher for desire. Their hunger, after all, is beyond instinctive, more akin to the reproduction and mutation protocol of a virus than a single-minded malicious monster. And so we feel for the vampire who crumbles to dust at dawn or writhes when a wooden stake pierces a no longer beating heart. The vampire’s posthumanism confronts us with human frailty, and much more: the human capacity for violence.

In contrast to the obsessive pursuit and violence the vampire’s human foes unleash, the vampire’s violence is seductive. Rather than resist, victims yield. They surrender. Far from resignation, their submission, though beyond their control, seems pleasurable, not fearful. They wander, like Lucy Westenra or Sookie Stackhouse, into the arms of their fanged lovers who consume them, savor them. Once bitten, they are irrevocably altered, but still stumble onward, transformed, unsure of whatever constitutes the new normal. Maybe a kind of brain fog lingers? Maybe they tried to convey what happened to them but found that words make a poor substitute for communication that happens on the cellular, even sub-cellular level, where viruses morph and mutate. Chemical exchanges of information communicate more rapidly, much more precisely, than clumsy words. Think pheromones. Think infection, contagion, airborne or fluid. And somehow this is not a world apart, not a mere fiction, but a world intricately interlaced with the human world as soon as we read the vampire as virus as desire: “Like a virus needs a body/As soft tissue feeds on blood/Some day I’ll find you, the urge is here,” sings Bjork in “Virus,” a 2011 release. “Like a virus, patient hunter/ I’m waiting for you, I’m starving for you.”7 The virus, like the vampire, can be sexy. Desire is not at all moral, if we follow the ancient Greeks; neither is a virus.

Consider barebacking. Even the Wikipedia entry for the practice of unprotected anal sex that gained traction in the waning days of the AIDS epidemic makes mention of both moral panic and the quest for transcendence. With HIV becoming more treatable, the risk of infection became fetishized. Compare that to the notorious COVID parties of the most recent global pandemic. Participants court contagion, whether “to get it over with” or to seek some other, deeper, darker form of jeopardizing the body and the self.

In “Erotic Ruination,” Kent L. Brintnall connects French philosopher Georges Bataille’s work on eroticism, religion, and the negative ecstasies of losing oneself deliberately to the “savage spirituality” of barebacking. Brintnall writes that “Bataille compels us to ask whether our desire to retain a coherent, recognizable sense of self—perhaps even our very desire to survive—is, in and of itself, ethically and politically suspect.”8 Why, in other words, are we so invested in resisting profound transformation, which for Bataille was psychic transformation? What are we so afraid of, so very eager to keep at bay? Is it the possibility that our selves may not be as unified or autonomous or independent as we have been taught to believe in this culture’s intellectual inheritance?

Brintnall follows Bataille in connecting the sacred and the erotic to “‘domains of violence, of violation.’ Disrupting and disturbing participants’ sense of corporeal and psychic integrity, of social and moral order, eroticism produces pleasure and terror, providing access to ecstasy”:9 ec-stasis, literally, being out of place, de-placed. He draws on Leo Bersani, who argues that “sexual pleasure occurs whenever a certain threshold of intensity is reached, when the organization of the self is momentarily disturbed by sensation or affective processes or somehow ‘beyond’ those connected with psychic organization.”10 For Bataille and Bersani, the self is “exuberantly discarded” in those sacred, profane, humbling, humiliating, and erotic moments. Barebacking may be a particularly dangerous form of courting infection, but flirting with disaster, with temporary loss of self, with surrender, seems to have a moment: “I don’t really care if it nearly kills me,” sings Maggie Rogers in “Shatter,” a song on her 2022 release, Surrender.

Los Angeles-based artist Jordan Wolfson, too, addressed surrender in a solo show in the summer of 2022: “I researched countless therapeutic and spiritual modalities and one thing they had in common was the idea of surrender—to yourself, and maybe even to God.”11 Visually, Wolfson’s research includes appropriated photographs of restaged Puritan harvest feasts. Modeled after the Mason siblings’ portrait by the 17th-century Freake-Gibbs painter, three Puritan children stand as the epitome of devotion, hands folded in prayer, heads covered in appropriately devout attire. The vibe is Thanksgiving, as they stand in front of a pile of zucchini, squash, and corn. Then Wolfson breaks the mood by drawing vampire fangs and arched eyebrows on their puffy-cheeked faces. In one fell swoop, the grateful white settler child as an emblem of innocence is recast as vampire, as murderous parasite.

A few black marks suffice to turn saccharine, homey, homophobic piety into an indictment of the founding violence that makes the United States. The questions keep coming: What happens when we flip the script and jot the vampire’s fangs on presumed purity, on genocidal whiteness? Which forms of kitschy visual seduction does the addition of the vampiric interrupt here? Who feeds on whom? In whose name is/was violence inflicted on whom? Who is meant to be seduced by devout white mock-vampire children? Can we think white supremacy as a virus, as deluded, depersonalized, insatiable desire?

Jordan Wolfson, Still from Raspberry Poser, 2012. © Jordan Wolfson. Courtesy the artist, David Zwirner and Sadie Coles HQ, London. Photo: Jonathan Smith.

Jordan Wolfson, Still from Raspberry Poser, 2012. © Jordan Wolfson. Courtesy the artist, David Zwirner and Sadie Coles HQ, London. Photo: Jonathan Smith.

Jordan Wolfson, Still from Raspberry Poser, 2012. © Jordan Wolfson. Courtesy the artist, David Zwirner and Sadie Coles HQ, London. Photo: Jonathan Smith.

Jordan Wolfson, Still from Raspberry Poser, 2012. © Jordan Wolfson. Courtesy the artist, David Zwirner and Sadie Coles HQ, London. Photo: Jonathan Smith.

Wolfson’s work does not stop there. In his prescient Raspberry Poser (2012), he shows CGI-animated red viruses hopping down busy urban streets and bouncing on living room furniture. The tentacled blobs drift through empty gyms and past photographs of spring break bacchanalia, always accompanied by a rousing soundtrack that samples, for instance, Beyonce’s “Sweet Dreams:” “You’re the perfect lullaby/ What dream is this/ You could be a sweet dream or a beautiful nightmare/Either way I don’t want to wake up from you.” In Wolfson’s vision, sexually transmitted viruses—from HIV to monkeypox—bubble like candy from airborne condoms that resemble champagne flutes before they gush into children’s bedrooms. Such viral exuberance eventually gives way to an empty condom floating ghost-like through abandoned home improvement projects. Desire depleted, the loop starts all over again: a reclining cartoon boy blows smoke rings that take turns spelling “yes” and “no.” And maybe the answer is both. Unlike the vampire lurking in the shadows, Wolfson’s virus is exuberant, triumphant, irreverent, a life form bent on reproduction at all costs, for no sake other than making more of itself. (Sort of like capitalism: profoundly amoral, with a penchant for annihilation, for making more simply for the sake of more, not based on need or necessity.)

The moral of the story: What we choose to surrender to may not always be “good” for us. Surrender yields different pleasures than conquest. Hegel knew this: his “bondsman” gains a kind of knowledge that the “lord,” enthralled by the imperative of mastery and conquest, never can know. There is something to be learned in the space of displacement, of negative ecstasy. It is a space of contagion, not purity. And this is where the virus as metaphor differs from supremacist visions: there is no purity. Maybe what the virus offers is a lesson about vulnerability. And connection. Not mastery, but submission. An expanded sense of the body, never autonomous, but intimate with so many non-human others who reproduce and procreate at uncanny paces, all the time.

The vampire, read as virus and as desire, offers us an opportunity to embrace becoming, stepping into the unknown, to surrender to the posthuman. The vampire dares us to say yes to what we do not, maybe cannot understand, not yet; to ongoing transformation, to so many skins that need to be shed, to reveal the dripping blood body beneath, as in Alex Kuno’s painting in The Dark Blue. Nicholas Vander Loop’s Lost Space Dracula (2022) imagines the posthuman body astride on a dolphin-tailed, rainbow-colored unicorn that bucks through interplanetary darkness in the company of a pod of space-dwelling manta rays. Christy Kirk’s drawings entwine female bodies with trees, picturing ecological enmeshment of human and non-human.

And it is this sense of the posthuman body—whether an ecologically inseparable body, a digitally entangled cyborg body, an ancestral body that manifests through us but does not begin or end with the individual—that sprouts and spawns right now like so many mushrooms after the rain: Melodee Strong’s Lineas de Sangre at NE Sculpture Studio, R Yun Matea’s They became ill and their pages were left blank at PAPA Projects, or Allison Baker’s Abject Permanence at Dreamsong all promise to further the conversation.

The Dark Blue is on view at Rogue Buddha Gallery through October 1, 2022. >> more information