Ziba Rajabi: Poetry and Home

A conversation with the 2023/24 MCAD–Jerome Fellow on her use of abstraction and Persian calligraphy to explore themes of distance, belonging, and home

Yi WAngCan you describe the moment or experience that initially prompted you to explore the themes of identity and displacement in your art?

Ziba RajabiI cannot recall an exact moment or a single experience since it was a collection of many different things, including language, social status, legal documents, skin color, etc., that led me to explore the complexities of my new identity in my art. My work is my essential way of making sense of the world and my surroundings. As soon as my flight landed in the US, I became a non-resident alien overnight; then, naturally, themes of displacement and, therefore, identity emerged in my work.

YWHow has your transition from Iran to the US influenced your choice of materials and techniques in your artwork?

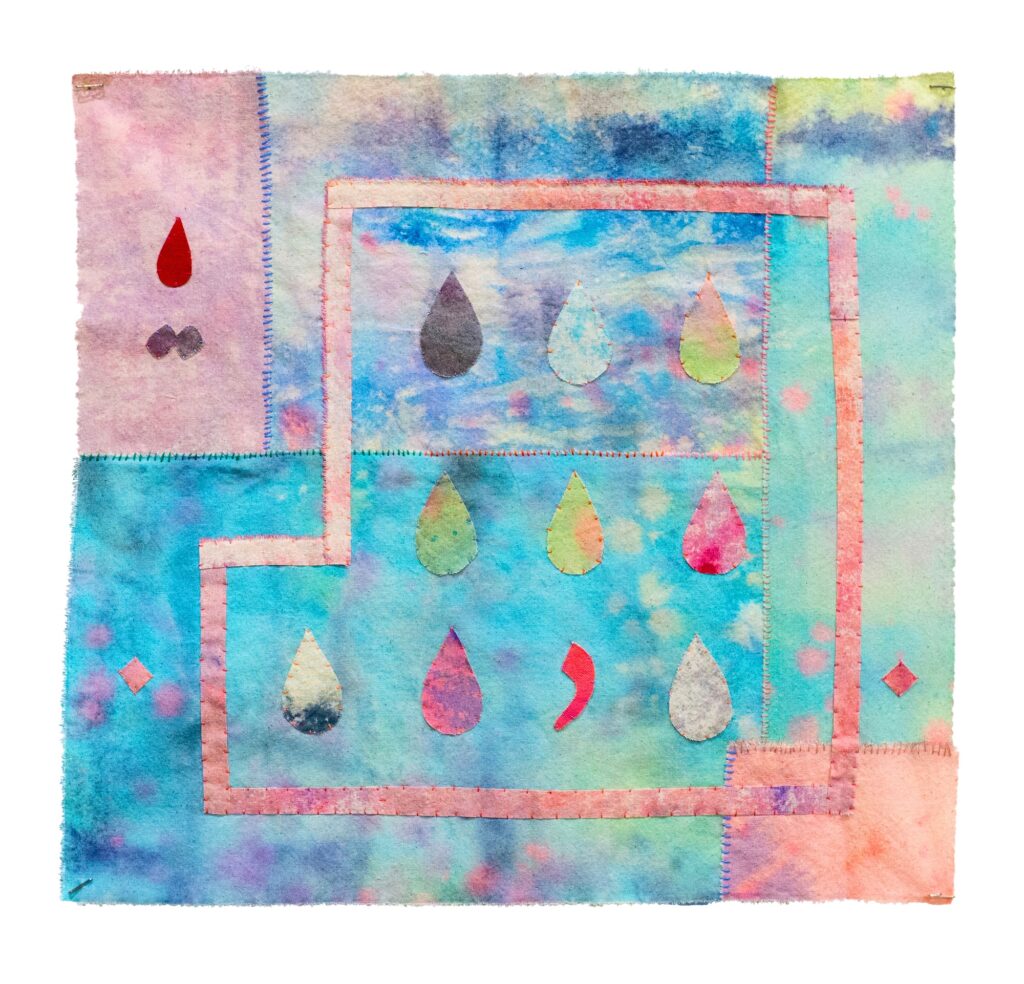

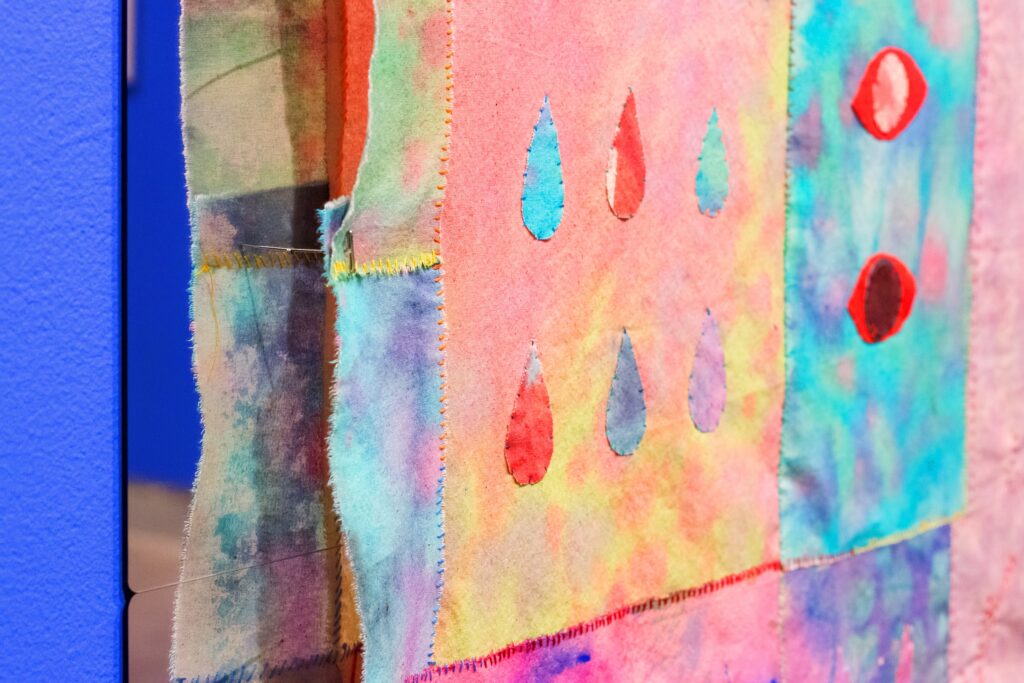

ZRMoving to a new continent with a temporary visa introduced a sense of suspense and instability to my life, as well as a constant consciousness that I may have to leave at any moment. Consequently, I was drawn to fabric for its inherent qualities, such as lightness, foldability, mobility, and malleability, which could convey the same feelings I was experiencing on a daily basis. So, painting on unstretched canvas led me to fiber and, therefore, textile-based installation.

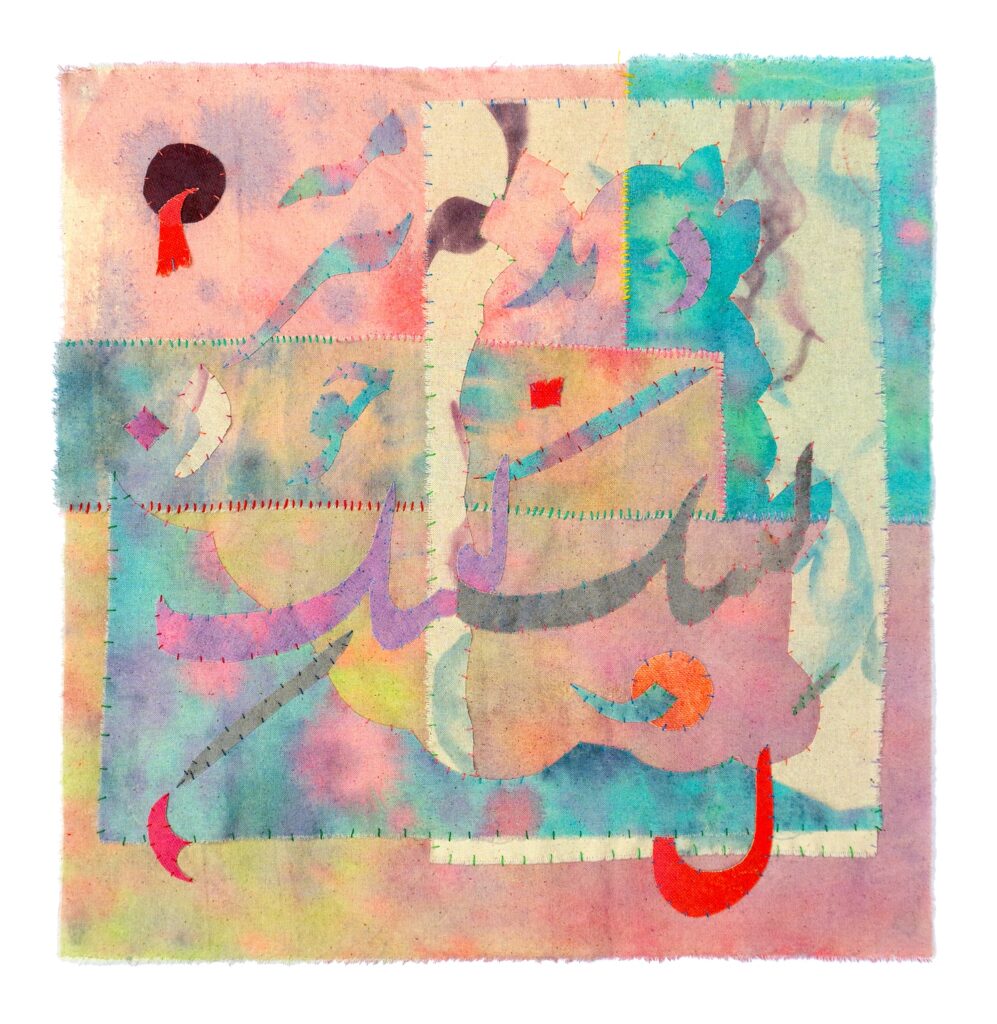

YWPersian calligraphy is a recurring element in your work. Could you talk about the process of incorporating text into your visual compositions and the interplay between legibility and abstraction?

ZRIt is an intersection of abstraction, language, sentiments, unfamiliarity, and resemblance. The source of the written component is mainly a verse extracted from a poem. I am interested in how abstract painting and poetry use ambiguity and sometimes metaphoric language–either visual or literal language–to create a space for interpretation and contemplation. Texts employed in these works are derived from a well-known Persian poem by Aref Ghazvini, “Hengam-e Mey,” which revolves around the love for the motherland, young martyrs sacrificing their lives for freedom, and feeling homesick in exile: “The bird in the cage, feels homesick for its land, as I do.” It was written in the early 1900s to honor liberation activists during the Persian Constitutional Revolution. Then, it remained in the Iranian collective memory and was revived and recited in future social movements, including the current women-led protest Women, Life, Freedom movement. This poem has been simultaneously a place for grief and courage for Iranians throughout decades and across geographical boundaries.

Formal decisions are made based on my personal sentiments toward a piece of poetry. They are informed by years of experience working as a designer, purely focusing on the form of the letters–not meaning–to create a composition, meanwhile using color to convey the feeling. For instance, the muted color palette used in the current works echoes my emotions at the time. I try to avoid articulating color choices, as I feel art does need to preserve some aspects unarticulated.

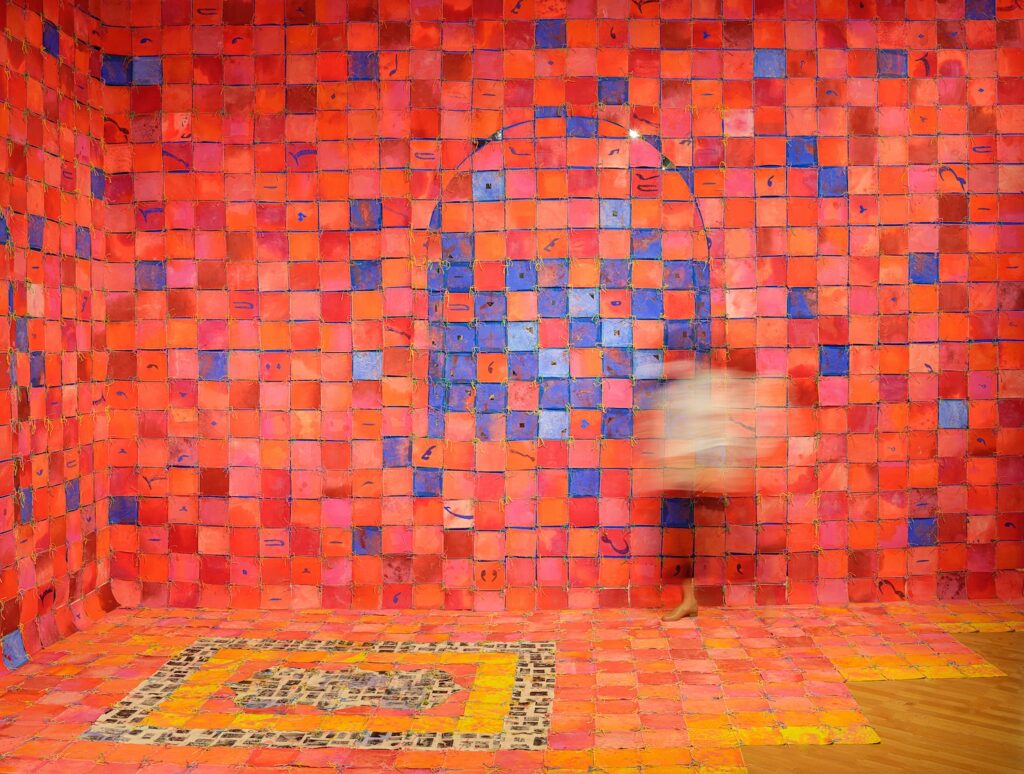

YWHas the process of creating The Glitched Home influenced your perspective on home, belonging, and the role of art in bridging physical and emotional distances?

ZRThe Glitched Home, a site-specific project at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, was about my experience of living away from home for a few years when I could only communicate with my loved ones in Iran through digital devices and see them through my cellphone or laptop screen. Therefore, their three-dimensional presence transformed into a two-dimensional existence on the screens made of pixels. I could no longer feel or touch my home and loved ones, so I made an entire home interior with more than 2500 tactile pixels. I assembled the installation on-site before the eyes of the visitors for more than six weeks, which allowed me to talk with people and also learn about their similar experiences, especially since it took place when the world underwent a global pandemic and physical boundaries.

YWYou’ve mentioned the use of poor image sources and domestic practices in your work. How do these elements contribute to the dialogue you’re creating around hierarchy, privilege, and politics in the art world?

zRThe source of my imagery, technique, material, and processes is a place for me to further explore the complexities of my identity in my work. I use materials and techniques that historically have been considered feminine, craft, and low–in the patriarchal Western art approach–in order to own them, reintroduce them in an unconventional setting, and create an image using alternative ways of mark-making, for instance, stitching vs. hatching on paper, or unprimed muslin vs. stretched canvas. Due to being away from my homeland, poor images on the internet are another source for my work, from protest photos and videos to low-quality images of Persian manuscripts and calligraphic pieces. For instance, the pair of hands in Only Tulips Grow on this Land is sourced from a photo of a young girl in the protest in Tehran that I saw on social media, which reminded me of my own hands, my sister’s hand, or my cousin’s hand, and all the complex emotions that it evoked.

YWThe emotional landscape of the Iranian diaspora, especially in light of recent events in Iran, plays a significant role in your work. How do you navigate these often complex and heavy emotions in your creative process?

ZRI feel I am still processing how to navigate this complex sentimental baggage in my work. It sometimes shows itself in the choice of a softer material, sometimes in the labor-intensive meditative processes, and sometimes in the story of the work. However, my new mantra is “recite a poem when feeling hopeless.” Persian poetry and literature has become an emotional refuge, as some feelings are untranslatable. Whenever I want to remind myself who I am, I read poetry. It connects me to my history and roots and reminds me of the vast array of emotions that I might have forgotten to feel. It feels like there is a place in my mind that is created by language, and I can always escape there to feel like myself again.

YWSince winning the Jerome Fellowship, has it changed your perspective on how you approach your work, or how has it affected your studio practice?

ZCIt definitely has. Now, I have a deadline, a cohort, financial support, and mentorship from fellowship admins. Also, the Jerome Fellowship has brought to my studio a sense of possibility and direction simultaneously, which is an odd, exceptional combination in creative practice.

YWIf you could describe your work in one word, what would it be?

ZRDistance.