Glitching the Glass Wall: A Conversation with Skawennati

A conversation with visionary new media artist Skawennati about cyber remediation, the magic in glitch, and exploring Indigenous worldbuilding through machinima

JULEANA ENRIGHTScreen culture is so second nature in our daily lives now, but your earlier works CyberPowPow and Imagining Indians in the 25th Century were conceived at the cusp of this phenomenon, when we were still discovering and exploring ourselves in cyberspace. What led you to explore new media?

SKAWENNATII sometimes call it love at first sight. Or seduction. There is an intellectual level of why I explored it, but I have to admit there was a more visceral, emotional and/or physical feeling that drew me to it.

I entered university around 1989 in Design Art at Concordia University. In my final year there was a new course offered, called Computer as a Design Tool. Our teacher, Don Ritter, taught us HyperCard. The big thing about HyperCard was linking files together, and that became the web as we know it, linking an image to a page or vice versa.

Around that time, Concordia got a new computer room with three Amiga computers—a computer built for graphics. With the Amiga, you were able to take a picture—I mean, now it sounds so trivial, but this was a big deal: that I could take a picture of someone and upload it to the computer and then manipulate it, because Photoshop didn’t exist yet.

Using that technique, I did a series named after a lyric from a Jesus and Mary Chain song: Lovers Tongue Tied and Tied to the Tongue. I took pictures of friends with their tongues sticking out and then I used the Amiga’s Digipaint tool to extend the tongues so that the couples’ tongues were tied together in various knots. Drawing that image just didn’t seem possible to me—or it would’ve been possible, but it would take me maybe weeks, whereas this took days.

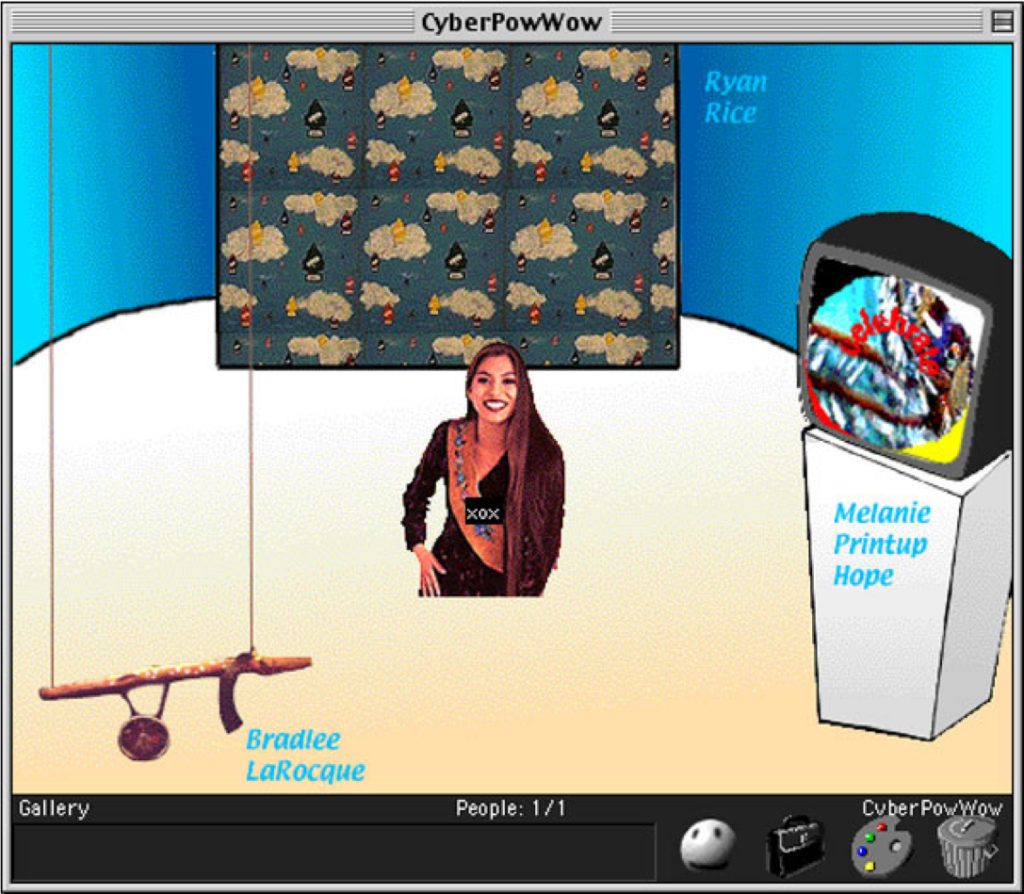

Skawennati, CyberPowWow, 1999. Featuring Skawennati’s avatar, xox, and the work of Ryan Rice, Bradlee LaRocque, and Melanie Printup Hope. Image courtesy the artist.

Skawennati, Audra Simpson, and Ryan Rice at the first CyberPowWow mixed-reality event at Oboro, late 90s. Photo courtesy Skawennati.

CyberPowWow at Rhizome. Photo courtesy Skawennati.

After leaving university, I lost my access to computers and an internet connection. But I discovered an artist-run center in Montreal called Studio XX (now Ada X). They were all about making sure women had access to these kinds of digital tools, and they would have these wonderful salon-style evenings called Les femmes branchées / Wired Women. One night they showed us a demo of this new software, The Palace. With what was going on in the rest of the world and in my world, I was looking for other Indigenous artists who were making contemporary art. And they certainly existed. I had my friends, Ryan Rice, Eric Robertson, and a few other people who were in Montreal, but I had gone elsewhere in Canada and met more First Nations artists who were doing this stuff and I was like, “We need to talk more. We need to get together more.”

This was in the time when phone companies charged for long distance, and that was very expensive. I thought The Palace would be this amazing way for artists to talk to each other because, if you could get access to a computer and an internet connection, it was free. Plus we get to be little avatars interacting in a graphic environment.

JEFrom The Palace, you discovered Second Life and expanded Imagining Indians in the 25th Century. Can you tell us more about how Second Life impacted your work?

SIn my presentation “My Life as an Avatar,” I talk about how Barbie was actually my first avatar. Far from feeling alienated or substandard through Barbie, Barbie made me feel empowered. I felt like she could go places that I couldn’t go. That’s exactly what an avatar does for me. In my presentation, I show a slide with Superstar Barbie and explain how I didn’t mind her blonde hair or white skin at all, or her boobs; what I minded was that she couldn’t stand on her own.

Then comes The Palace where I learn about avatars, talking to one another over the internet, customizing your environment. After The Palace died, Second Life arrived. I go in there and what do I see? Barbie and Ken walking, running, and flying. You can customize Barbie and Ken; you can customize the environment. I’m like, “Oh my, I’m home!” I fully got that space. It was just so natural, such a familiar space to me after these other experiences. I wanted to explore this space and I’ve been very comfortable there ever since. It’s comfortable but it still challenges me. Technology is always changing. Second Life as a platform is idiosyncratic and sometimes I have to fight with it—just like any partner.

But it wasn’t just the existence of Second Life that impacted my practice. A few planets aligned at that time. My partner and husband, Jason Lewis, and I wrote a grant as a pilot project to create an Indigenous research network. He was like, “I think this idea we’ve been talking about for years—the conversation that was started in CyberPowWow of an Aboriginally determined territory in cyberspace—is a great research topic. And we can use that as a way to think about our presence in cyberspace.” I can’t remember exactly if we wrote the grant in 2005 and I discovered Second Life in 2006, or if it was the other way around, but we got the money.

I also happened to have a story I’d written—just sitting in my back pocket—that would be perfect for a machinima. (That story became TimeTraveller™.)

Skawennati, Stepping Out, from TimeTraveller™ series, 2010. Image courtesy the artist.

Skawennati, Face Off from TimeTraveller™ series, 2010. Image courtesy the artist.

Skawennati, Family in the Sky from The Peacemaker Returns, 2017. Image courtesy the artist.

Being in this place that was sort of familiar, but also brand new, and the whole process of being able to customize the avatars and learning how to tell the story, was also very satisfying and exciting.

I felt like I’d discovered this rich medium where I could say a lot. At that time in my career when I was just trying to make TimeTraveller™, it’s not like people were knocking on my door trying to show my work. It was quite the opposite. I was like, “Where can I show this? To whom?” I was more just thinking about how I could develop this work and what I could do in this medium.

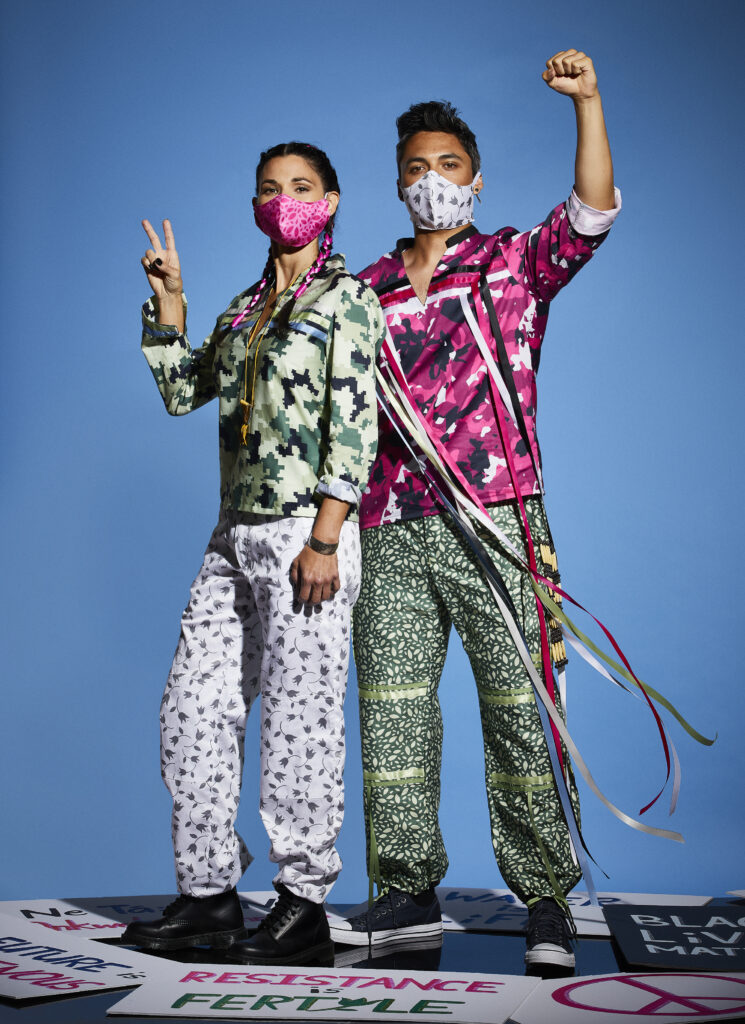

Looking back, I’ve started to see my time in the virtual space as almost staging, making something there first before I make it IRL—or AFK (away from keyboard) as Legacy Russell says. Slowly there have been invitations and reasons to try things AFK and produce them with physical materials. And I see it as a metaphor. I was hoping to affect the future with my work, hoping to realize a certain future. So when something I imagined in the cyber is produced in the so-called real world, it feels like that future that I want is getting a little closer.

JEYou make art from your perspective as an urban Indigenous woman, but also as a cyberpunk avatar. And this is the concept that I’m kind of obsessed with, because you were just talking about AFK. Nathan Jorgenson’s critique on digital dualism identifies and problematizes the split between online selfdom and real life, and the idea that we should be moving away from IRL to AFK because they don’t operate in isolation of each other. It’s the polar opposite. We’re producing these selves and these digital skins we develop and don online, but they actually help us understand ourselves with greater nuance.

I think some fear that, as we move deeper into the digital age and we develop these communities in cyberspace, having this continuous online presence is affecting our ability to maintain connection and community beyond the screen. But your work seems to challenge and subvert that. There’s an empowerment in cyberspace, not a disconnect from humanity.

SYes, I do think that’s true. And I understand why people think the opposite is true. I understand why people think that if we spend too much time in these worlds in cyberspace, we won’t be able to connect to people. I think because the way we’ve been brought up to think about Western thought and science fiction—the way it’s been talked about for generations—sets up that dualism or that binary. But I don’t think it really exists. It hasn’t played out the way they thought it would or the way they could imagine. And that’s cool. That’s how things roll. You think it’s going to be a certain way and then it isn’t. You think that the internet is going to make information free, but oh no, actually we have to give all of our personal stats in order for it to work. There’s always a cost, right?

JEWe thought there were going to be cars in the sky!

SWhere are the jetpacks?

JEWhere’s the hoverboard?!

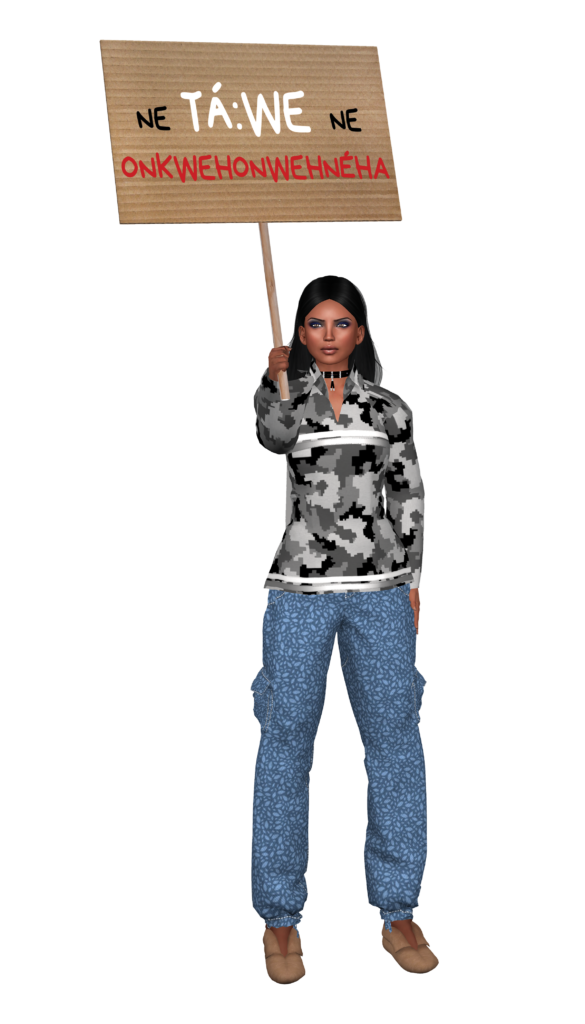

SIn the end, you are always in your body. I have this piece called Dancing With Myself. It’s a diptych composed of a machinimagraph of my avatar, xox, and a photograph of me dressed just like her. We are standing in the same pose, mirroring each other. What a lot of people think is happening in that work is that I’m trying to be like my avatar. And I am trying to be like her, but I think she’s also trying to be like me. They are compatible. It doesn’t have to be one or the other. We can have both, we can be more. All my life, I was told by other people you’re only half Mohawk and you’re only half Italian. You’re never fully in one world. But I’m not 50%; I’m 200%. I’m more; I’m both. And I feel the same way about cyberspace and so-called real life.

JEReferencing the cyberpunk avatar also reminds me of Donna Haraway’s asserting herself away from the lexicon of “human” because, as a classification, it historically others bodies, whether it be people of color or queer bodies. I’m also thinking about Juliana Huxtable’s work with avatars—specifically There Are Certain Facts That Can’t Be Disputed—where she kind of wrestles with the way that our identities and sense of history are both warped and heightened by virtual enactments. With avatars being the vessels for inhabiting other personas and histories, what assertion and disruption does your avatar make?

sOoh, that’s a wonderful question. I believe that my avatar asserts our indigeneity, hers and mine. I’m also saying that I’m allowed to be Indigenous and be cyberpunk. I’m allowed to not be of the land. The Land Back movement is extremely important and the theft of the land has to be recognized. But I sometimes feel that I’ve been tethered to the land in a way that is not comfortable for me, in a way that I actually don’t believe my ancestors felt. There was a responsibility to the land but to be forced to stay in one place, like the reservation system did (and still does) and other parts of the colonial project did to us is not how I think it was supposed to work.

So I feel like my avatar says a little “fuck you” to tying me to a piece of land. Don’t get me wrong, it’s great to feel like you belong to the land. I live in my territory, so I don’t have to long for it; I’m right here. But sometimes I want to go elsewhere. And sometimes elsewhere isn’t even on earth, it’s cyberspace. There is a thing that it does for me. I get this feeling of excitement and joy and questioning in cyberspace. It’s got a different taste, flavor than wandering around the planet. I’m so privileged that I actually have been able to wander the planet, but I’m still interested in this other space.

JEI want to talk about visual sovereignty. CyberPowWow and TimeTraveller™ both enact this through the use of Indigenous politics, identities, voices, perspectives, presence. I just watched a virtual talk with professor, artist, curator, and art historian Jolene Rickard on Indigenous Visual Sovereignty where she said, “Sovereignty is an ongoing resistance to dispossession.”

If we think about this dispossession specifically in terms of land, then the concept of visual sovereignty or virtual sovereignty, occupying a virtual territory is so expansive and limitless for Indigenous people. How do you use visual sovereignty as a means to inhabit and reclaim contemporary virtual spaces?

SMy Wampum Belts of the Future series is a good example. There is specific imagery in a wampum belt, such as the friendship belt where we have the traditional figures, how our people depicted them way back in the day. They look like very abstracted or simplified human forms holding hands.

I wanted to use visual language that’s recognizable, especially to my people, but also recognizable worldwide as an Indigenous material with the beads and leather, as well as the form. And I wanted to make a wampum belt that would mark some future event, an empowerment wampum belt. I took the imagery from the friendship belt and looked up “empowerment” on Google. Almost all of the imagery from that search had people with their hands in the air, so it was a simple, even elegant, change. Instead of using tan colored leather, I used white because white is the color of the future, of a blank canvas, of infinite possibility.

If you saw The Peacemaker Returns, Iotetshèn:’en says we used materials from each of the planets to create these beads, a new meaning is formed. And here I possibly contradict myself, but it’s not a super contradiction because we can be both on the land and in cyberspace. The beads are a way of recognizing the land. They’re part of the sea, they’re part of the shore. They come from the earth and we use them to talk about our ideas and concepts.

JEI’m thinking about refashioning old into the new. TimeTraveller™ as a series is a union of so many realities. It’s a love story, a piece of science fiction, a history of colonialism and Indigenous resistance. Something that stood out to me in the description is that it’s a story about media and remediation, refashioning of “old media” in the new—“old media” being our stories, languages, cultures, ancestral ways of knowing and new media being all the realms of cyberspace.

Can you talk more about cyber remediation and the use of Indigenous past and futures in these episodic pieces?

S I’ve noticed that you can’t imagine the future without the past. As soon as I think about the future, I have to ask myself, what in the past do I want to bring with me to the future? Another form that my question has taken is why do I want to be Indigenous? Why have we resisted assimilation? In other words, what is so great about us? As I learn the stories and protocols of my people, I’m finding the answers. Like our Thanksgiving Address, the Ohen:ton Karihwatehkwen, a beautiful piece of oration handed down for a millennia, in which we simply give thanks to all the natural world on a regular basis. Practicing gratitude was encoded into daily life!

I think that that is something that we can give to greater society, to bring about peace and justice. And that’s what my ultimate goal is. It’s for all of us to live happily with one another, healthily with wellness, with our minds being clear and open to possibility and to helping one another. I like the idea of an Indigenous future because I think about the positive aspects of the past that I have learned about that I want to see happen again, and I think can happen again.

One of the things that I spoke about at my WAM talk was how capitalism is a human-made thing. It is not a physical feature, like gravity! It is something that we created and that we can deconstruct. And it did not seem to exist before contact amongst our people. It seems we shared resources and lived in harmony with the planet like they say. And we could really do that. It would be very beneficial to many people if we lived that way again, or something very much like it.

JE I’m thinking about the work of Shameekia Shantel Johnson, of the black beyond collective. Their exhibition _origins created a space that was dubbed “a Black femme paradise.” It was all about recuperating the “glitches” of a feminism which had foregone them by unraveling the themes of ancestral Black femme utopia. I feel like this parallels re-imagining Indigenous futures and Native utopias. Ancestral knowledge has a place in the future. Traditions have a place in the future. It feels like it’s an oxymoron, but it’s not. How does your work use glitches in white feminism and white supremacy to ensure Indigenous femme presence in virtual worlds?

SI don’t feel I’m using the glitch in that way. I kind of wish I was, it’d be cooler. But I think it wouldn’t be wrong to say that I am, either, if that’s what you saw. I see the glitch as being, like, the human in the tech. Or maybe the magic. I’m really just thinking about the glitch on a much less conceptual level. In TimeTraveller™ and in all my machinimas, I think what’s happening is you’ve got this imagery that doesn’t look real. It looks cartoon or fake—I mean, you know it is not a human you are watching. I don’t mind that, it’s not supposed to look real, but I want you to know that there’s some real to it, there’s some truth, there’s some history, there’s some knowledge that really happened or is happening. Where that reality comes from most, I believe, is from the sound, especially the sounds of the people’s voices. Episode 03 is about the Oka Crisis, and Brad Larocque—the warrior who faced off with a Canadian soldier in the famous photograph from 1990—watched it. And he wrote to me and was like, “Oh, to hear those Kahnawá:ke accents again.” I really think that the voices, the music, and the sound effects are what make it feel real. Sound creates space; it brings emotion. What I think happens when you watch TimeTraveller™ is the storytelling and the sound are pulling you in and making you believe that this is real. But then you see the hand go through the face or you see this glitch, this weirdness, this clunkiness that makes you go, “Oh, I’m watching something. I’m not in this; this is not real.” There’s a tension, a pull and push that makes it successful.

In TimeTraveller™, when Karahkwenhawi (the protagonist in our time) somehow gets technology from the future, it is described as a glitch. And she says, “I guess it was magic.” That’s how I see the glitch. These things that can’t be explained. In The Matrix, the glitch in the system is deja vu. Deja vu feels kind of magical to me. I love how in the movie they call that a glitch in the system.

I think that a glitch in the system is something that can be hoped for. A glitch is usually seen as a mistake, but it’s also how we get to perceive or experience or feel something that we are not supposed to feel. The system was not designed to make you feel that, but oh, there it is. The ghost in the machine is the glitch and it’s not always bad to see a ghost.