Places, Portals, and How to Look Wrong

An episodic journey through this summer’s art offerings in the Twin Cities, including exhibitions at Weinstein Hammons Gallery, Form + Content, HAIR + NAILS, David Petersen Gallery, Night Club, and Dreamsong

Coming Home, Cooper’s Pond, Groundwork, Far Away Is Still Somewhere, Buoy, How to Look Wrong—a smattering of titles from this summer’s exhibitions around the Twin Cities. From Night Club to Dreamsong, HAIR + NAILS to Form + Content, I go looking for a pulse, a pattern in the art on view. I do not have to search long: place emerges as a central concern. Places imaginary and quotidian allow artists to tell stories of posthuman futures and to grapple with past pain. Together, these representations and abstractions of place conjure a moment hungry for connection—with the land that meets our bodies, the horizon line of our thoughts, and the plane of perception that orients how we move through the stories that shape our worlds. Politically charged and elusive despite its messy materiality, place acts as anchor and portal, keeping us rooted and propelling us into the unfamiliar. The closer we look at a place, the stranger it gets. And of course, the act of looking itself is integral in the ways we encounter and connect with place.

What follows is a journey with six stops, a journey that ultimately prompts some questions about art in a state of entropy, insulated from critical dialogue by a cocoon of autobiography and myth, bubble-wrapped in like-mindedness. What is it that we want from art? Is it to see our values and concerns mirrored, validated, and hence remain unchanged? Or are we willing to encounter transformative and challenging ways of looking that are less concerned with correctness of all kinds, and curious instead about the possibilities of inventing new problems, of shifting the gaze, and—possibly, imperfectly—changing the eye of the beholder?

Ruben Nusz, Frieze (for V.G.), 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Weinstein Hammons Gallery.

Ruben Nusz, Asclepius, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Weinstein Hammons Gallery.

Ruben Nusz, HTLW (7), 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Weinstein Hammons Gallery.

First stop: The Weinstein Hammons gallery.

How to Look Wrong is a show of minute and perfect whimsies. Ruben Nusz’s 19 new paintings on view at Weinstein Hammons could be described as masterful exercises in geometric abstraction and explorations in color theory—but that would be missing something elusive: perhaps a sense of not exactly secrecy, but of a private joke that is less funny ha-ha and more steeped in a cosmic serenity, a detached amusement that dares to “look wrong”—in appearance and practice. Look the wrong way or look in a way that defies the proper; look askance and astray and away.

Bright and impeccably precise circles form the basis for much of Ruben Nusz’s visual vocabulary. They intersect and overlap. Shifts in scale and perspective alter their contours—and some seem to suffer a kind of temporal drag, as if they were lagging and dragging, and thus extend into flat but tubular-looking wormy shapes. (Does anyone remember the director’s cut of Donny Darko?) The spaces these paintings conjure do not add up, like an MC Escher painting sans the architecture. They ripple and create rifts, fracturing a reliable visual plane. Their spatial incongruities become more compelling the longer one stares. Is there one right way to look? Or is there a tad of irreverence, a flaunting of delectable wrongness?

The particularity of place is abstracted here, distilled and distorted; the desire to orient thwarted. Some of the works are all jostling surface, while others conjure a theatrical sense of depth: Asclepius, named for the Greek god of medicine, features a portal in blue, a central red staff with a winding snake-like form. Riffs on art history—A Married Couple looking in the Mirror (after Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait)—vaccines, and folklore make for an eclectic mix of titular references. Mirrors, myth, and microscopy meet with cluttered suggestions of maybe-horizon lines. The artist’s vision problems add an edge to How to Look Wrong that turns the ostensibly playful series into a different kind of exploration: not of pathology per se, but a question of what the wrongness of looking a certain way might reveal about the neurotypical, the taken for granted. How do we suspend an economy of attention that seems designed to elude detection?

The visual paradoxes of Nusz’s work propose profound metaphors about right and wrong, normal and not, “proper” priorities and an attentiveness gone awry. What if we start looking at places we’re not supposed to notice? To look in ways we have been discouraged to practice? And what if—one more speculative question—what if we noticed that the spaces we live in, along with the stories we tell and are told, simply do not add up? Do we despair? Or take a page from the existentialists’ playbook and make our own meanings? Do we turn, as the artist suggests, our attention from the murderous Sisyphus’s endless plight to the stone’s involuntary journey up and down the mountain?

Joyce Lyon, Cooper’s Pond #1, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Form+Content Gallery.

Joyce Lyon, Cooper’s Pond #2 (log), 2023. Courtesy the artist and Form+Content Gallery.

Joyce Lyon, Cooper’s Pond #3 (green leaves), 2023. Courtesy the artist and Form+Content Gallery.

Joyce Lyon, Cooper’s Pond Study #3, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Form+Content Gallery.

Installation view of Cooper’s Pond, 2023. Courtesy the artist and Form+Content Gallery.

Next stop: Form + Content Gallery.

The discipline of looking at what is there to see—Thoreau’s famous dictum—comes to mind when spending time with Joyce Lyon’s most recent body of work, Cooper’s Pond: Recent Reflections. Nine drawings with oil stick on paper invite us along to practice such close attention to the particularities of place. What is perhaps most compelling about Lyon’s work is the way these images conjure the patience of getting to know a place over time, of returning time and again. The intimacy of the work grows from the iterative practices of walking, taking time, noticing, and sensing the seasons of a place through a body’s changing capacities. There is a tenderness in these studies of looking.

At times, the drawings keep us on the water’s surface, rich with reflections of trees and undergrowth close to shore. Some take us into the dark, plunging us below the surface where light fades and only specks of floating color stand between our gaze and the murky depth—which is not some sublime abyss but a fecund pond of possibility. And perhaps most intriguing are the images where up and down, surface and depth, become indistinct. These moments of disorientation feel oddly valuable perhaps because they allow us to suspend the habit of pretending that we already know what is there to be seen. Without a reassuring sprig of green leaves or fall foliage, Cooper’s Pond becomes a strange space, its familiarity an illusion sustained only by not looking closely enough: the more nuanced our attention, the more mysterious the place.

The drawings look great on a screen—which is where I first saw them—but only after spending time with them do their texture and grit become apparent. Some of them are framed and mounted behind glass. Though there is nothing unusual in this form of display, this body of work succeeds in making the glass surface felt as another layer that adds a different sort of reflection to the pond scenes. What we are able to see and which degree of disorientation we can tolerate—and for how long—hinges on our capacity to be present with and for the work. Otherwise, the glass acts as a mirror that reproduces nothing but the self. And that, as Louise Glück notes in her 1994 essay “Disinterestedness,” reduces art to a diary of encounter that only ever reflects the self – nothing else, certainly not the artwork, the world it investigates, or the universe it conjures. And the art-as-mirror-of-self precludes something else: the possibility that said self might change. Lyon’s drawings are an open invitation to ponder change, inside and out.

Gregory Rick, Uprising goddess, 2023. Courtesy HAIR + NAILS.

Gregory Rick, Heart or feather, 2023. Courtesy HAIR + NAILS.

Gregory Rick, Mountain top, 2023. Courtesy HAIR + NAILS.

Gregory Rick, Dope game, 2023. Courtesy HAIR + NAILS.

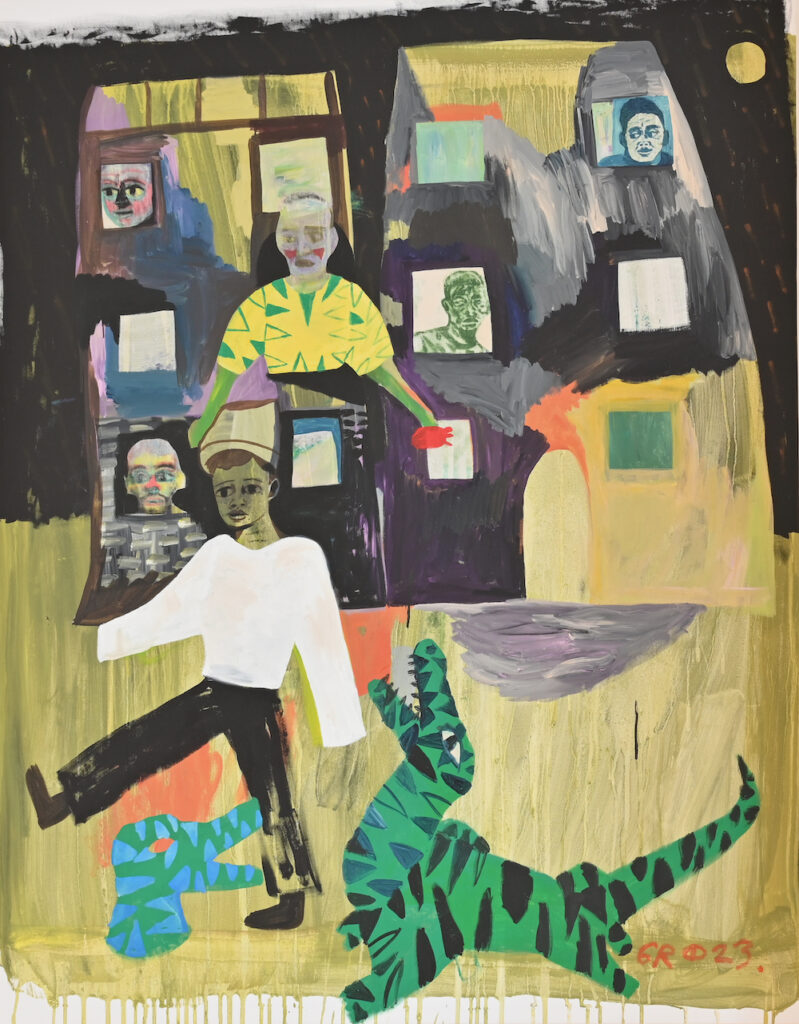

Third stop: HAIR + NAILS.

Gregory Rick’s paintings are dense, busy, crowded, and a little claustrophobic at times. Set entirely in urban spaces, they reliably feature skyscraper facades gridded with windows. So many faces and eyes stare from these dark holes. There is no privacy here, just a constant sense of breathless being-watched. Religion, too, enters into these scenes: hellfire burns bright red, crosses rise from domes, titles make biblical references—such as Solomon’s wisdom, Locusts and wild honey—while elsewhere, a baptismal pool promises absolution for the spirit and the flesh.

Collectively titled Coming Home, the paintings seem animated by a centrifugal force that pushes bodies and buildings together. Rooted in the visual language of graffiti, their collisions at times seem oddly geometric, as seen in Mountain top, when horizontal floating bodies and upright buildings tangle into some warp-and-weft like clandestine pattern that feels ephemeral, already poised for dissolution. There is an urgency in Rick’s work, a sense of speed amplified by the traces left by paint running down the canvases, as if control was only a momentary phenomenon at best.

Steeped in historical references, the work blends politics and myth: in Uprising goddess, a red-bosomed figure in a vaguely pharaonic headdress occupies the lower edge of a violent confrontation between police and protesters above. The moment is ambiguous, like many in Rick’s paintings: is the goddess at risk of being trampled? Or does her ancient presence suffuse the hostilities that rise above her? The red figure returns in A requiem for the environment, where her red locks suggest wildfires and hellfire. A handwritten incantation accompanies the flames.

Coming Home offers no return to childhood solace, no revisiting or once treasured places of belonging. Instead, this return is marked by the trauma of war—Rick served in Iraq—and the war on drugs in the US (Dope game). Place becomes dynamic, less fixed site and more ever-emergent space. The past invades the present, and timelines tighten and compress. In the temporal disorientation that results, only magical creatures seem to inhabit Rick’s paintings with a semblance of breath, spaciousness, and ease: In Heart or feather, an alligator rears its head, dog-like in its attempt to catch a boy’s attention who is goose-stepping out of the picture frame. Countdown to safety features six cats and dogs—some with their teeth bared though their miens are not entirely unfriendly, guardians rather than predators—who bear down from the night sky on three human figures. They seem oblivious to these nocturnal visitors, though. In Locusts and wild honey, it is a red horse, looking partially skinned, its head turned in wide-eyed alarm, that seems the only creature with a fighting chance to leave the mayhem behind. Divine judgment and blessing collide in the quasi-mythical places Rick’s work conjures. The ordinary is transmogrified here: quotidian places teem with the energies of past events that spawn archetypal creatures.

JJ PEET, Ceramic History Monster, 2023. Courtesy David Petersen Gallery.

JJ PEET, Buoy, 2023. Courtesy David Petersen Gallery.

JJ PEET, Portal, 2023. Courtesy David Petersen Gallery.

JJ PEET, Viewing Shroud, 2023. Courtesy David Petersen Gallery.

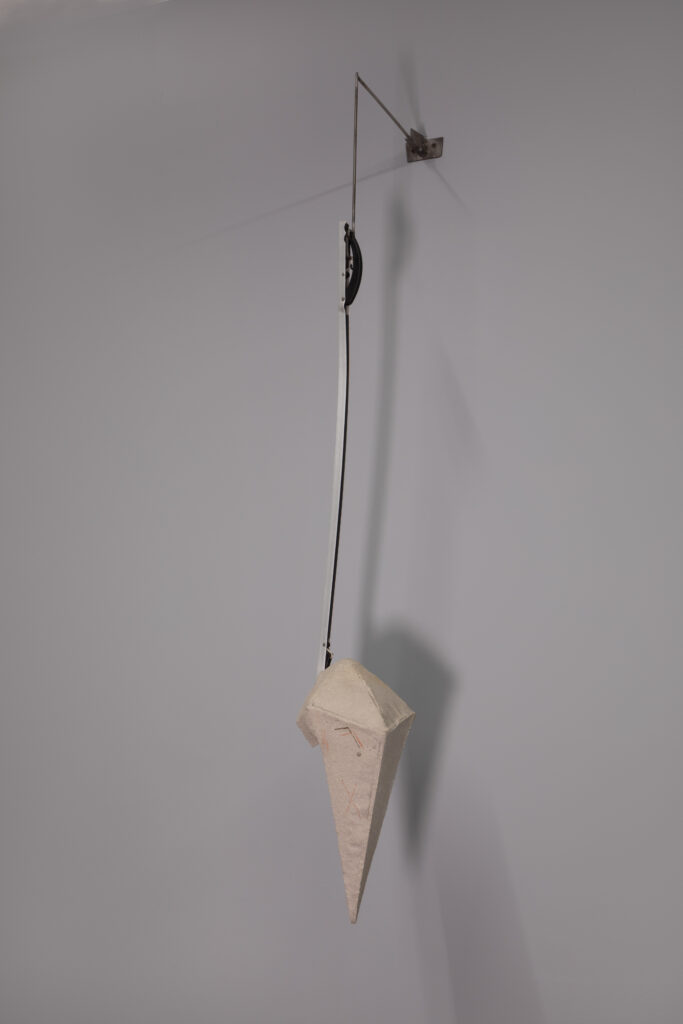

Fourth stop: David Petersen Gallery.

A mythical aesthetic also infuses JJ PEET’s work in Buoy. The paintings and sculptures all embody parts of a complex political parable that is part futurist fiction in material form, part social critique: the story centers the Mass of Democracy, the crew of a spaceship called The Material Ship. With the help of a Viewing Shroud (2023), fashioned from stoneware, aluminum, steel and acrylic, a mystical staff and a vessel called the Proxy_Cup, the nomadic crew travels to “unravel mysteries” and to track objects from other dimensions. Complete with a villain or two—the Ceramic History Monster (2023), the Void Maker, and an entity known as Direct Doom—the storyline remains oblique enough to allow the objects on view to conjure rather than illustrate PEET’s vision. The aesthetic is less steam- and more gutter-punk—an idiosyncratic, gritty DIY-meets-retro-sci-fi look.

PEET’s work is fun to spend time with. Irreverent and imaginative, Buoy transforms the urgencies of 21st-century life—the confounding lack of political and civic action on global warming, the ravages of extractive capitalism around the globe, and even an art world dominated by capital—into myth and magic. Of course, turning to sci-fi to articulate critiques of the status quo is not new; but the emphasis on myth is noteworthy: “The revival of magical beliefs is possible today because it no longer represents a social threat,” writes Silvia Federici in Caliban and the Witch. “A belief in occult forces does not jeopardize the regularity of social behavior.” And so, PEET’s story includes a Seer, a Shaman, a Conjurer, and ancient enchantments—in sync with recent exhibitions on spirits, demons, and astrology.

Paintings, in this work and world, act as image portals that offer access to uncharted parts of the cosmos. Modestly sized, they invite close viewing. They do not explain themselves, which is refreshing, but exist both as portals and, in PEET’s narrative, as “Holds:” “the crew keeps Holds, pocket-sized realms, held close. These miniature worlds serve as reminders of the magic that surrounds them and the wonders waiting to be discovered.” Whether portal or anchor, paintings act as traveling contraptions to access new corners of the multiverse or to act as grounding devices. They also—and this is not inconsequential—act as reminders of the magic that is already there, a point that echoes Jane Bennett’s assertion that the world is no bleak, doomed, and disenchanted place but a space full of mystery and magic—if only we take the care and the time to look.

Fidencio Fifield-Perez, Cutting & Pruning, 2022. Courtesy Night Club.

Fidencio Fifield-Perez, dacament (detail), 2016-present. Courtesy Night Club.

Fidencio Fifield-Perez, dacament, 2016-present. Courtesy Night Club.

Fifth stop: Night Club.

The title of Fidencio Fifield-Perez’s exhibition insists that Far Away is Still Somewhere. The show pairs incredibly detailed paper weavings with meticulous acrylic paintings of potted plants on a series of used envelopes that chronicle the artist’s interactions with various forms of authority: postal stamps from universities, galleries, and artist residencies document his professional accomplishments, while the correspondence with the USCIS, the branch of the US government responsible for enforcing immigration policy, make palpable his long fight to gain legal residency in this country. As a beneficiary of DACA, the legislation that grants prosecutorial discretion in the case of children who arrive in the US without proper documentation—a piece of law that only recently was almost repealed—the artist knows what it feels like to have your personal life and whereabouts scrutinized, evaluated, and judged. Being so completely at the mercy of immigration officers is nothing but harrowing.

This precarity is palpable in the tight control evident everywhere in the work. Nothing here is left to chance. The paintings are precise and perfect, as if to offer a counterpoint to the loss of personal authority in the face of institutional might. The struggle with these pervasive disciplinary powers lends the work its urgency. The potted plants make for a compelling contrast. Their presence offers a semblance of continuity and constancy in an itinerant artist life. Native to faraway places, these plants survive and even thrive in their containers. The only print, a linocut reduction, shows the artist cutting and pruning a cactus: a gloved hand holds a central stalk, while the other sinks a pruner’s blades into green flesh. The scene adds yet another element to the question of who has agency and wields the authority to trim and shape another’s life.

The artist’s autobiographical investigation withholds more than it reveals. We only see the discardable traces of official correspondence. The paintings reclaim the paper sheaths that have already served their purpose. The plants, too, with all their mesmerizing detail offer little that is more personal. Though the work attests to the oft-quoted feminist insight that, yes, the personal is political, Fifield-Perez tightly controls the affective charge—or lack thereof—that his artwork delivers. Yet it is exactly this tight control that makes the work so effective, since the very question of control resonates deeply with the lived experience at stake in Fifield-Perez’s work. There is no pathos here, but a quasi-clinical look at the psychological effects of looming deportation and displacement.

The paper weavings pair pattern—the artist connects it to the imprint of sleeping mats on skin, a sensual memory of childhood, perhaps of belonging —with other minimal imagery. Tear-shaped forms interact with the pattern that also vaguely resembles a chain-link fence. Once again, the technical skill, patience, and perfect craftsmanship in these works are hard to miss. And once again, the work remains aloof. There is no performance of private pain here for white eyes, just an unsettling degree of constraint—unsettling because it suggests that the disciplinary mechanisms of institutional authorities have made an imprint that reaches further than skin deep.

Groundwork, 2023. Courtesy Dreamsong.

Moira Bateman, Bog Etude No. 3, 2022. Courtesy Dreamsong.

Kahili Robert Irving, Concrete Nodes and Moon Chunks / Street Stars and Fragments (Mixed Vessel), 2022. Courtesy Dreamsong.

Groundwork, 2023. Courtesy Dreamsong.

Sixth Stop: Dreamsong Gallery.

The mounded shape of a female body burns on the ground. Shown alongside more contemporary art, Ana Mendieta’s Silueta Series (1980) has lost none of its poignancy. The work’s mythical-political sensibility infuses the entire group exhibition, Groundwork. Carefully considered and competently curated, the show brings together works by 17 artists whose widely varied practices all touch on the significance of place. Some use soil and mud in their work, like Stephanie Lindquist, Alexa Horochowski, and Moira Bateman, whose Bog Etude No. 3 (2022) is a marvel: silk dyed and coated with bog mud and wax, the fabric hangs like a shroud, a veil, heavy and light at the same time, evocative and concrete, curiously ethereal and material.

Groundwork also features photography, painting, ceramics, weaving, and sculpture. Activist interventions meet the deep time of geologic imagination alongside rituals of grief, care, and radical holding. A dispassionate study of digitally reconfigured rocks—Rocks on Rock Texture (2022) by Mathew Zefeldt—suggests a modality of encounter far removed from the actual grit, texture, and liveliness of the ground. Moments of humor—Gudrun Lock’s photographs of found underwear in various stages of decomposition or Kahlil Robert Irving’s diorama composed of “moon chunks” and “street stars” —alternate with drawings that give voice to acute solastalgia, the experience of loss that hinges on the transformation of familiar environments. Taken together, the works share a material intensity and grapple with what care—caring for land or for a place, each other in a time marked by global warming and other catastrophes—could look like.

Groundwork asks all the right questions and touches themes as relevant as they are timely: the politics of decolonization, the urgency of imagining intimate ecologies that replace thinking of “the environment” as something somehow mysteriously separate from human lives. Nothing is heavy-handed in this constellation of works. The curation invites lines of connection and dialogue that seem capable of sparking, if not exactly new, still much needed conversation and repair. Groundwork is as foundational as it is profound. True to its title, the exhibition also shows art that grounds, calms, and offers reminders that amid despair, it is still possible to find connection and joy: Tasting Tart Cherries and Raspberries at Karamu (2020), Lindquist’s soil paintings on cyanotypes, conjure such moments of small, shared pleasures. “We will hold each other through this fire,” promises Nikki Praus in poetry molded from dirt on the sidewalk.

Why, then, does Groundwork leave me—well, if not cold, then only lukewarm?

The best answer I can offer is this: the show does everything right. And somehow my inner curmudgeon promptly starts craving something wrong; something that not only embodies the questions and concerns that plague all those who are awake and alive in this age of climate crisis when land and creatures are hurting from the cumulative consequences of our actions and, even more, our collective inaction. Mind you, “lukewarm” is not bad: when ice cubes have melted in a glass of water, the lukewarm remainder is in a state of maximum entropy, a kind of end game when order has dissolved, molecules no longer urgently skip from one state to another but lazily drift around without much direction. The result, in creative terms: the stagnation of like-minded-ness, of bubble talk, a place where we all know the problems and the questions to ask. We also know not to burden art with the task of coming up with answers.

What remains, then?

As I am staring at this cluster of exhibitions like so many tarot cards, place looms large as a conduit to communicate, a portal to the possible. Whether fictional or actual, home or not home, human-made or post-human—the relationship to the more-than-human world churns in these shows. Two ways of turning to place recur: on the one hand, a turn to personal myth-making; on the other, an appetite for the autobiographical.

The latter’s appeal seems clear enough. Amid the no-longer-new skirmishes of call-out culture, choosing the autobiographical is one way of dodging conflict. After all, who can argue with someone else’s lived experience? Exactly no one. Yet this turn to autobiography, memoir—or, as Maggie Smith recently dubbed it, “tell-mine”—is a move that can also insulate and immunize from critique and engagement. Of course, this is not all the autobiographical does. But the risk is there, even in work that meticulously connects the personal to the political, as in Fifield-Perez’s case. What makes Far Away is Still Somewhere compelling, though, is less the political messaging and more what the work reveals despite itself: when the work moves in a way that defies expectation and, perhaps, even intent.

The autobiographical is also present in Gregory Rick’s Coming Home and Joyce Lyon’s Cooper’s Pond. Lyon’ work only implies rather than thematizes the artist’s presence. She is perceiving consciousness, reflector, and masterful practitioner—of walking and drawing. One body of water acts as portal to countless possibilities of noticing. In contrast, Rick’s work engages the autobiographical more directly and imbues experience with a mythical dimension. Like JJ PEET’s elaborate political fable, the mythical in Rick’s paintings seems rooted in an impulse to explain, to make sense of the inexplicable: why not picture a fiery-haired goddess of destruction dancing in the devastation of wildfires? Or an ancient deity whose presence sparks or feeds off conflict? Maybe there is a source comfort in couching our stories—individual and collective—in terms of myth: this has all happened before. This is not my story, my trauma, alone. Never has been. If the autobiographical offers one kind of buffer, myth insulates in a different way. Both modes do not readily lend themselves to critical dialogue and exploration. They simply are. And is this not art’s prerogative—to simply be? And yet, is there anything simple about being? If critique, Maggie Smith proposes, is an investigation of possibility—what, if anything, do we stand to lose in the absence of such curiosity?

I find myself pulled back to Ruben Nusz’s work: how to look wrong. Do we dare look wrong? What happens if we choose not to over-determine and insulate the work with autobiography, if we steer clear of fruitful fictions—but go looking for that strange, oblique point where a new angle may open up, a new alignment may become possible; when planes of perception shift, and we plunge beneath the surface, though maybe we cannot be sure of where exactly we are. With our certainties upended, maybe looking wrong could help invent new problems.

For further viewing:

More food for thought—and shows I did not have a chance to see but that promise to tie into the ideas I stumbled on and through here:

- At Interact Gallery, California Girls pairs artworks by Eric Sherarts and David Bauman. The press release asks, “Can a drawing transport us to the places or people we wish to revisit? Enthralled by Hawaii after a family trip in 2005, David Bauman (1969-2019) made the islands and their primordial landscapes the focus of his work, drawing intricately patterned volcanoes, craters, and clouds from memory.”

- PAPA Projects features works by Lexi Herman, Miranda Ribeiro-Vecino, and Siobhan Wood, collectively titled Nudes Descending into Lake Michigan. Per press release, “Here, bodies of water become a modality of what moves through and between; the waterways, personal mythologies and one another.”

- Ruben Nusz’s How to Look Wrong is on view at Weinstein Hammons Gallery through August 12, 2023. >>more information

- Joyce Lyon’s Cooper’s Pond: Recent Reflections is on view at Form + Content Gallery through July 29, 2023. >>more information

- Gregory Rick’s Coming Home is on view at HAIR + NAILS through July 23, 2023. >>more information

- JJ PEET’s Buoy is on view at David Petersen Gallery through August 12, 2023. >>more information

- Fidencio Fifield-Perez’s Far Away is Still Somewhere is on view at Night Club through July 22, 2023. >>more information

- Groundwork is on view at Dreamsong through August 5, 2023. >>more information