Transformations in Progress

Lightsey Darst weighs in on the premieres recently offered up by the 2008/09 McKnight Artist Fellows in dance in the McKnight SOLO show: Mary Ann Bradley, Sam Feipl, Kats D Fukasawa, Justin Leaf, Karen Sherman, and Roxanne Wallace-Patterson.

WHAT MAKES A PERFORMANCE COMPELLING? What makes a dancer riveting — makes the dance come alive for the viewer, rise up as a lived moment, translated into the viewer’s own dreams and history?

It doesn’t take too much watching to figure out the answer to this question. The most exciting dancers are those who seem to be alive on stage — who appear to be, that instant, growing, changing, learning, feeling. Physical prowess is nice, but without that spark of presence, the dance is merely a performance, an enactment of moves.

Tall as this order is, across a dancer’s career, excellence becomes even more demanding, because a dancer must actually change and grow (and be able to show that growth) in order to remain compelling to experienced viewers. If the sensation that you deliver is always the same one — always a plunge into sensuality, say, or always an epiphany of freedom — it stales.

An unusual concert offers a lab in these ideas — the McKnight SOLO show. Every two years, recipients of the McKnight Artist Fellowships for Dancers perform new solos created especially for them. Since the dancers pick their choreographers and often guide the material, SOLO is the dancers’ chance to show off their transformations in progress — where they’ve been, where they’re going, what they have that we knew nothing about.

Karen Sherman‘s modest Floor Plan, a meditation on the life of homes with a little demolition, a little nostalgia, and an incongruous brass score, choreographed by Dan Hurlin, doesn’t show anything we haven’t already seen from Sherman. She’s fast, strong, and she can stare a hole through a brick wall; we knew that already. But then Sherman is best known as a performer in her own work (for which she has also received a McKnight), so perhaps this piece, more open-ended and airier than her own choreography, offers her new ways forward.

Ways sideways, under, backwards seem to be more the theme in Kats Fukusawa‘s butoh Fragment of Adam, choreographed by Katsura Kan. In clownish white gear, holding a bouquet of blood-red roses, Fukasawa flops across stage; the resulting mess of powder and petals appeals and appalls. In slo-mo, he extends one finger, all his fingers, then his hand, until finally he’s waving back and forth all the way across his face, like a transatlantic immigrant in a black-and-white film. Thudding delta-level music gives way to bells, wind, waves, and the mostly earthbound Fukusawa gets active, hopping around frenetically with arms and legs extended, like a cross between a baby bird and the Vitruvian man. Does all this constitute a step forward for Fukusawa? Hard to say. He holds the eye for a good long time here, definitely. But am I the only one oppressed by the didactic turn of so much butoh, its “your little mind shall be blown!” insistence? Also, why can’t American butoh (which both dancer and choreographer reference in the program notes) relate a little more to its context, as Japanese butoh originally did? All this othering needs a little grounding to be truly mind-blowing.

With her long flexible limbs, Mary Ann Bradley seems built for epiphanies and angelic interventions, but she declares independence from that version of herself with SubVert, a dance film/performance choreographed and directed by Shawn McConneloug (with a dream team of Nor Hall, Andrew Welken, and Chris Lancaster collaborating). SubVert haunts the lobby, hallways, and rooftop of the Southern in the company of a strangely driven ditz who runs into, among other things, a wax foot, a cicada in a sardine can, a miniature version of herself, and a dark diva with batwing lashes and three claw toes. Bradley convinces in this minor key as she hasn’t been convincing me lately in the major, and you’ve got to rejoice for a dancer who’s learned something about herself and charged boldly into new territory. But I wish SubVert had more impact overall. It sinks towards the trivial — too much ditz and jitter, not enough diva and shiver.

______________________________________________________

SOLO is the dancers’ chance to show off their transformations in progress — where they’ve been, where they’re going, what they have that we knew nothing about.

______________________________________________________

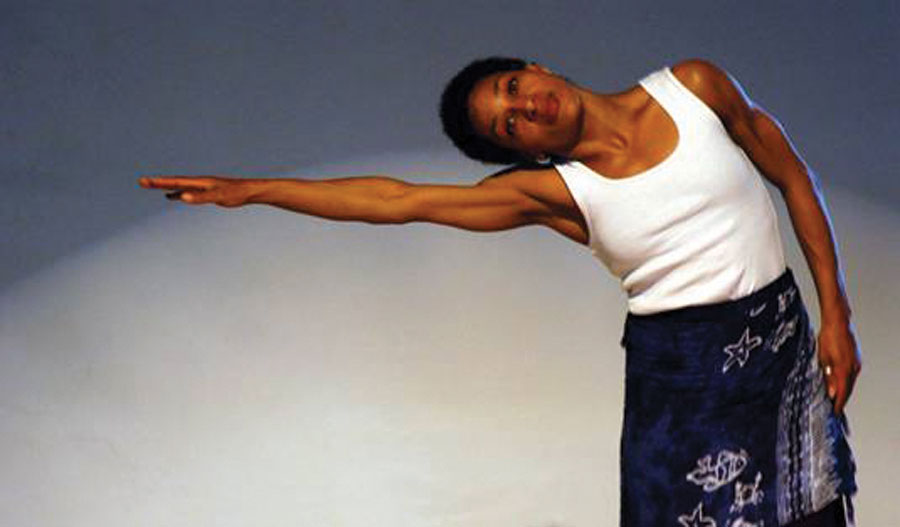

Roxane Wallace-Patterson is a queen of surprises. Soft as a lullaby when she shuffles with her head down or her large, innocent eyes on you, she’s sharp as a paper cut when she chooses, and sudden as lightning. Vincent Mantsoe’s Kutu doesn’t transform Wallace-Patterson or even “showcase” her so much as it gives her air and light, a place to be. My mind wandered all over during this quiet piece, but I’d call that parallel meditation, not dramatic failure. The stops and starts of the dance, Wallace-Patterson’s various paths across the stage, the rather noodly music (field recordings of African musicians), Wallace-Patterson free-floating among the elements of herself — all this encourages the viewer to do likewise, to seek and find, forgive and give away.

More quiet came from Justin Leaf, with John Kelly’s Cohesion. You’d think a dance portraying a soldier’s discharge or resignation from the army because of his homosexuality would land like a grenade, but no. Cohesion feels intimate, with its bittersweet little crossed-arms dance to “Beautiful Dreamer,” its undressing (goodbye, fatigues) and redressing, its onstage audience (like a subcommittee of watchers) who at last break into song. And Leaf takes a step forward here as an artist, with less trying to be and more being than I’ve seen from him before.

Life on stage reaches its apex in the evening’s last performance, Sam Feipel dancing Jennifer Hart’s The Lamb. This strenuous and dramatic work, with the dance often taking place at the edge of the harsh music, or the roving lights, or the dancer’s ability, takes on — you guessed it — the suffering of Christ. But just as John Kelly keeps Cohesion above polemic, Hart holds her work beyond simple evangelism — more Caravaggio, less The Light of the World. Feipel, who in seven years at Minnesota Dance Theatre has become known for an open, easy style, here throws himself around, crawling, scraping the walls, contorting his limbs and yanking out every ounce of energy; he pants audibly throughout.

If you didn’t know Feipel’s work, though, what would you see? He’s not a visceral or creaturely dancer; he can do things, but he doesn’t leave you in awe of what he just did. He doesn’t rebound off the walls with boyish energy, and he’s not an ironic charmer, who knows better and knows you know better, too. In The Lamb, Feipel doesn’t always know how to hold a dramatic stillness, how to impose on the audience. In fact, you could probably dismiss Feipel and Hart both as old-fashioned, out of date. But to do that, you’d have to (a) forget that the postmodern is only one aspect of the contemporary and (b) ignore the intensity of dance and dancer, their restless search for honesty, for a way forward. And you’d have to ignore Feipel’s purity of approach and expression — a quality it’s tempting to call spiritual. He’s an Apollonian in a world given over alternately to Dionysus and to Athena, and that makes him interesting.

For those who know Feipel’s dancing, The Lamb is a fascinating moment of confrontation with that outer world. It suggests an inward renovation of which his freshly shaven head (Feipel has had a ponytail since he was five, he says) is the outward sign. At least, I hope it’s renovation. I’ve been told that Feipel is getting bored with his dancing life. I hope that means he’s going to find more different and difficult things to do, like this dance — not that he’s going to leave the field.

Two more general notes on the evening. First, another viewer observed that all the pieces share an insistence on gravity, on weight, and that many share movement vocabulary — which is surprising, given that the choreographers practice in different genres (butoh, ballet, contemporary, African, even puppetry) and come from all over (Japan, South Africa by way of France, New York, here). So few extended phrases, so little hang-time — what’s going on?

Second, Jeff Bartlett‘s lighting looks terrific all night. Dramatic or natural, warm or cold, the light, like the dance, is alive.

______________________________________________________

Noted performance details:

SOLO: Premiere performances by the recipients of the 2008-2009 McKnight Artist Fellowships for Dancers – on stage at the Southern Theater in Minneapolis July 8-11. The 2008-2009 McKnight dance fellows include: Mary Ann Bradley, Sam Feipl, Kats D Fukasawa, Justin Leaf, Karen Sherman, and Roxanne Wallace-Patterson.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Originally from Tallahassee, Lightsey Darst is a poet, dance writer, and adjunct instructor at various Twin Cities colleges. Her manuscript Find the Girl has just been published by Coffee House; she has also been awarded a 2007 NEA Fellowship. She hosts the writing salon, “The Works.”