This Art Show Dares You to Participate

If there are no labels on the wall, no readily available didactics, how does a viewer navigate oblique, conceptual art to figure out what they're seeing? A new sculpture show at the Soap Factory aims to find out (with mixed results).

I ENTER THE SOAP FACTORY AND THE GRAVITY OF A MASSIVE STRUCTURE near the front of the show immediately captures me. The first section of Kelly Kaczynski’s engineering spectacle, Tilted (Twinned) Stages, seems to lean impossibly, yet securely against the room’s pillars. I resist its pull for a moment to look for some educational material, didactics or essays that might offer any insight. The problem is, curator Shannon Stratton wants to disrupt precisely this impulse; she wants “to problematize current fashionable notions of participatory, relational and social practice.”

With just one sentence Stratton has negated my intrigue, my search for understanding. I make my way through her compelling albeit overwrought essay — replete with repetitive conjectures, subtle wisdom, and theory-laden jargon. I wonder for whom Stratton is writing this, because it’s certainly not Jane Q. Public.

Contemporary art, she generalizes, includes “participatory and relational practices, platformist practices, interactive and multi-vocal practices,” while contemporary sculpture is specifically a “multivalent ‘platform’ whose defining features are continually re-evaluted and re-defined.” Eventually a thesis emerges from this thicket: Resonating Bodies proposes that the broad function of sculpture is performative, and encourages viewers to engage with the work physically, to walk around it, look over and under, but don’t step on it. This exhibition implicates the audience’s involvement as a necessary component of the works’ completion. Stratton writes that the viewer is not merely a passive bystander but serves as “interlocutor, as motor, as witness and implied force.” The difficulty of this exhibition begins with that contradictory, confused intent.

Despite the need for viewer engagement, the presentation of Resonating Bodies hardly welcomes audience involvement. As I read her essay and walk through the space I feel less like a “force” than I do an excluded guest. Both as a curator and as an academic Stratton appears aloof: alienating the audience does not “problematize” contemporary participatory projects, it’s just annoying.

In her essay, Stratton reframes the exhibition paradigm, labeling institutions and artists ‘hosts’, the audience a ‘parasite’, and the actual experience of the art work as a ‘scripted space.’ I agree with her overall criticism that “hosts” needlessly water down art with overbearing explanations, but Stratton has responded by designing a show, ironically, just as burdened with pretentious scholarship and lame didactics.

Ideally, a curator should provide insight and historical context — opening doors and drawing maps. At best, the curator serves as an unobtrusive guide, a translator for the art — and when engaging with opaque conceptual works, we need that guide more than ever. Stratton is no such curator. She has commandeered the role of host, not facilitating but actually interfering with any hope the viewer might have for illumination. Fearing a diluted art experience, Stratton effectively severs all educational communication by tying up meaning in exclusive, cerebral acrobatics and obscure, if not completely oblique descriptions. The motivating principle behind the participatory experience encourages an exchange of ideas: I want to know what the artists think; I want to know what Stratton thinks, and I want to know what you think. When an exhibition offers access to none of these, the art becomes illegible to the viewer and therefore remains incomplete.

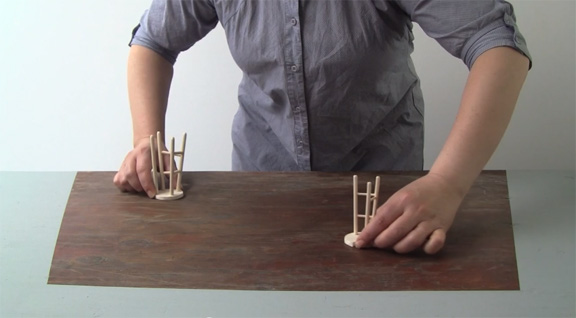

Resonating Bodies offers no labels for the sculptures on view, just convoluted symbols designed to correspond with each artist, the key for which you passed unknowingly at the show’s entrance. Hidden on the walls and stitched across large cubes at your feet are QR codes for interviews, none of which uploaded for me; by way of the QR codes, you also access Judith Leeman’s work for the show, preposition and prosthesis, a series of muted videos recording a body, cropped at the head, shuffling tiny four-inch-tall stools, some of them incomplete, across a table. The interviews and related media are available for those patient enough to find them, but, Leeman says, “no one (is) required to listen, no one (is) expected to discuss.” This wordlessness seeks to “trouble the demand for explanation.” As if silence is the solution.

What “educational” focus there is in the exhibition reveals Stratton’s contempt for participation — and presumes that viewers will have smartphones. My own phone happened to run out of batteries while I was visiting. Why post such obstructive didactics when the Soap Factory already has knowledgeable and friendly docents?

______________________________________________________

I want to know what the artists think; I want to know what the curator thinks, and I want to know what you think. When an exhibition offers access to none of these, the art becomes illegible to the viewer and therefore remains incomplete.

______________________________________________________

The initial gallery holds Kaczynski’s first “twinned” stage, two peculiar wooden “pods” by Conrad Freiburg, and one of Ben Fain’s exciting detritus sculptures — a car door with rebar adorned with glass bottles. In the next room I find Kaczynski’s second stage, several more pods, a TV hung before a huge tarp inexplicably littered with graffiti, and a junkyard of terrible beauty. In the third space, speakers hang above a fleet of chairs set on risers, arced toward the corner. I can’t discern much about the noises — something melodic comes from the speakers over there, and an annoying mishmash of sounds from the TV behind me makes me itch.

While Fain’s motley sculptures capture the rudimentary concision of a Basquiat, and a refreshing, raw honesty, his video installation is frankly nonsense: he’s caught in a post-modern whirlpool, rebelling against any urge toward narrative structure or coherence. But I’d much rather praise his sculptures than deride his video. If the paintings in the cave of Lascaux show us a way of life as it once was, Fain’s motley sculptural forms predict a way of life as it might yet be. They look to be the work of future ancestors, restless in some dystopian landscape and rummaging through dead towns to produce sawed-off tire rims, car doors, old mufflers and sheets of metal cut out in the shapes of hands, house plants and bodies. A pole skewers a skateboard; shelves make space for familiar objects — toilet paper, plastic plants and water bottles — to be arranged like relics. This future feels near.

With his pods, The Central Mountain and The Central Mountain is Everywhere, Freiburg mixes industrial and organic design to create claustrophobic spaces, curiosities that invite you inside but challenge you to stay. The pods function as architectural forms, existing simply as aesthetic objects, but also as uncomfortable spaces which sculpt noise. They are structured voids, transmitting anxieties of both potential and purpose: defying our impulse to fill the space while prompting us to wonder why such emptiness unnerves us in the first place.

Built just big enough not to fit into a single gallery room, measuring 15 feet-by-23 feet, Tilted (Twinned) Stages calls to mind acts of voyeurism, visibility and vulnerability. I stand beneath the stage, behind the “performance”, secluded and secure. Kaczynski has installed an angled mirror in a hole just off-center; its gleam catches my eye. To satisfy my curiosity and see what’s reflected there, I have to trust the pillars’ strength will hold. Ducking beneath beams, I am within the sculpture — engaged, afraid, emboldened and then delighted. Because there I am: I am in the mirror.

While I generally dislike Stratton’s didactic obfuscations, she sometimes successfully achieves a balance between mystery and ambiguity, enchanting the viewer with works like Sarah Black’s and Jillian Soto’s Three Times Around the Long Way. Inspired by the American choral tradition of sacred harp singing, the Elizabethan folk-song “Heigh-Ho/Rose Red” leaks through 60 individual speakers in the gallery, each hung above vacant stools sitting across three sets of risers, all facing a broad corner. Standing before the installation, you’re enveloped in murmured words about surviving life and death, layered together to become something different each new moment. Black and Soto plan also to “harvest” the voices of visitors, inviting gallery-goers to record their own versions of the song; eventually the artists will orchestrate a cacophony including all our voices. That’s participation.

Once Stratton roots her exhibition essay in a discussion of the works themselves, her ideas get some traction and she finds a strong, convincing voice. Beyond that, though, the argument is so belabored, so maddening that I find myself inordinately focused on it. I’m more inclined to critique the flaws in the style and substance of Stratton’s rhetoric than I am to appreciate the actual art work it should be pointing me toward. With such a ridiculous title — “Reciprocal Adaptation & Rewriting Scripts & Are We Having Fun Yet? or, Rejections, Refractions & Twins: A hypertext interaction” — I can’t help but wonder if this is one great, obnoxious and ironic ruse. Perhaps Stratton is offering her own essay as an object lesson in poorly designed didactics, the likes of which we’ve all seen in so many conceptual art exhibitions. Surely she’s trying to be obtuse. Maybe this whole thing is an incredibly clever, barbed satire on institutional and curatorial efforts at “inclusivity.”

Or, maybe I’m giving her too much credit.

Either way, while I appreciate the offer she extends in Resonating Bodies, to claim my own agency and make meaning for myself from the wonderful work on view, I’m not sure this experiment in manipulating viewer experience and strategies for engagement really works – as a joke or in earnest. The lack of information is too great to overcome. The host must give the parasite more sustenance.

______________________________________________________

Related exhibition details:

Resonating Bodies is a group exhibition curated by Shannon Stratton, featuring new work by six American sculptors: Sara Black & Jillian Soto, Ben Fain, Conrad Freiburg, Kelly Kaczynski, Judith Leemann. The show will be on view at the Soap Factory in Minneapolis from June 15 to August 11. Find additional media and artist information on the gallery web page: http://www.soapfactory.org/exhibit.php?content_id=595.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Nathan Young graduated from Macalester College and will attend graduate school in the fall where he plans to study the intersections of art and economics. He still doesn’t own any works of art. Find him on Twitter: @nrp_y