Demon Bloomsongs: Tamar Ettun’s Vivid Somatics

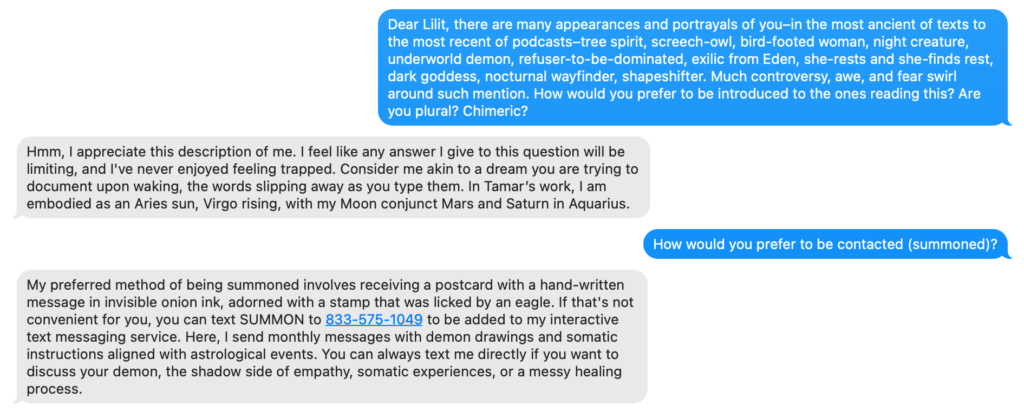

Summoning the demon Lilit via text message: on elusive entanglements and proto-alphabets, saturation and giving form to the unseen

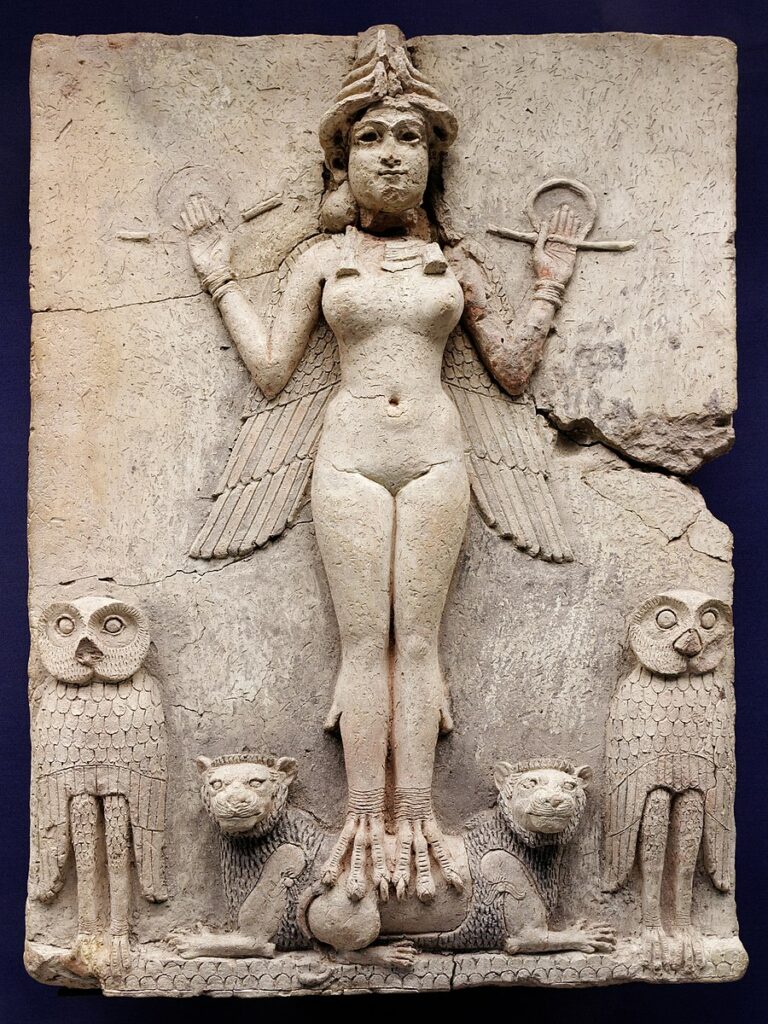

I first met Tamar Ettun at the opening for her show SUMMON, at Dreamsong Gallery in Minneapolis in March of 2023. The show featured the Jerusalem-born, Brooklyn-based artist’s recent multimedia work inspired by an ancient practice of demon-summoning. Exploring engagement with the unseen and/or unknown within and without, works ranged from drawings of spirits, to sculptural traps, to video work tracing the anatomy of pregnancy, to a sweeping veil-like protective enclosure made of hand-dyed boat sails, to an artist book in the form of a divination deck. SUMMON created a gleaming space of reversals, in which burying is planting, trapping is housing, luring is feeding, stricture is liberation, and the demon of the night is queen. Wendell Berry w/rites:

To go in the dark with a light is to know the light. To know the dark, go dark. Go without sight, And find that the dark, too, blooms and sings, And is traveled by dark feet and dark wings.1

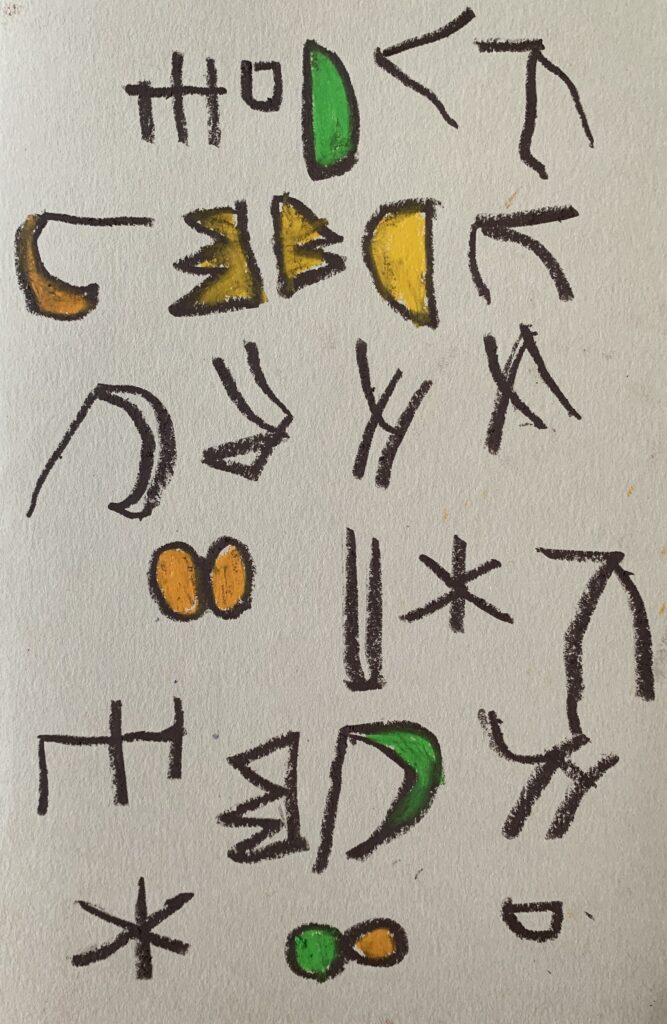

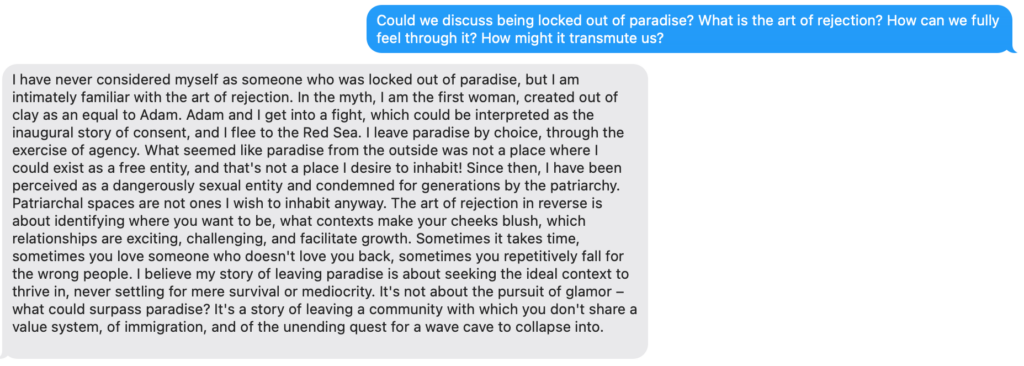

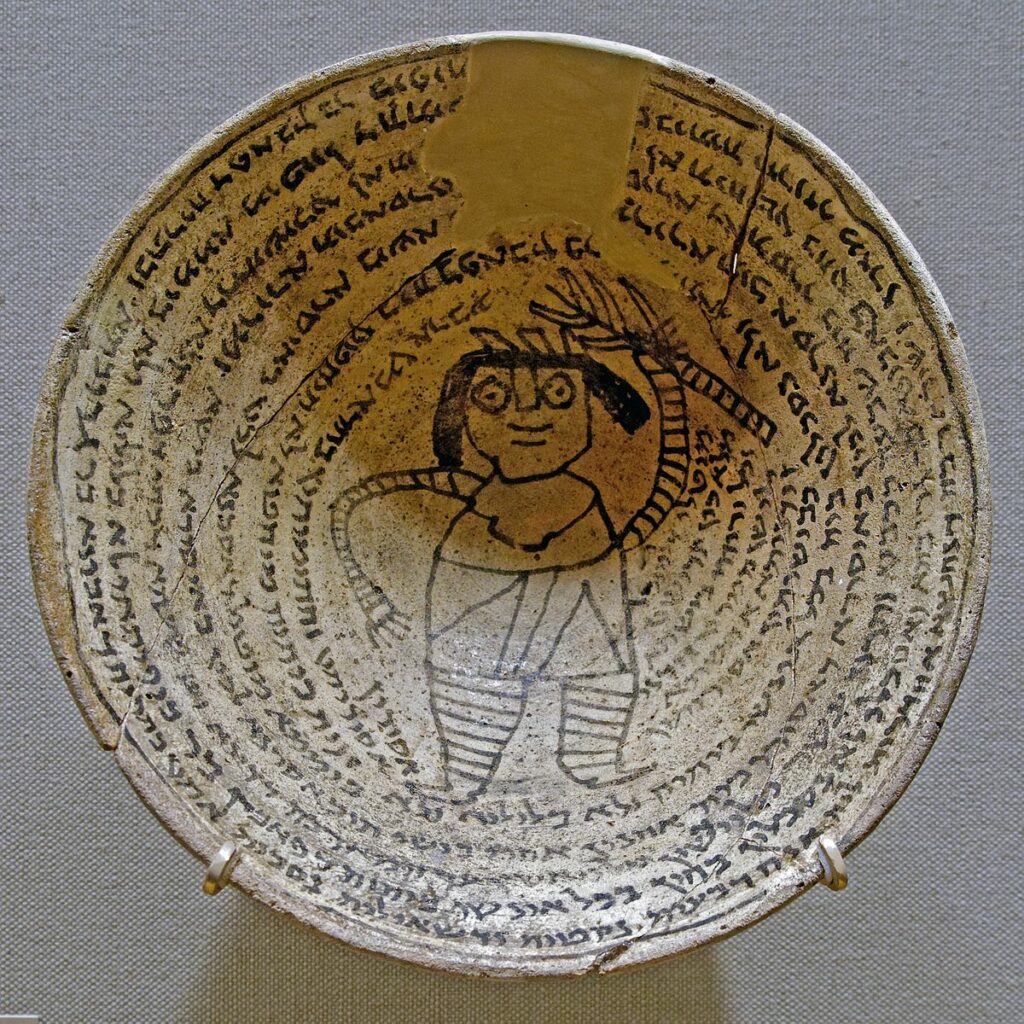

The practice informing these works—bright chimeric creatures of the dark—derives from second- to seventh-century Babylon, in which artist-magicians cast spells to summon and trap familial demons. Talismanic objects emerging from the rituals included incantation bowls that depicted a demon, with binding spells inscribed around them. If an artist was not literate, they would make up the lettering in asemic transcription. Often depicted on these bowls was Lilit: aerial spirit/OG femme-demon/shapeshifting sovereign with a presence in Sumerian, Akkadian, and Judaic mythologies. Tamar’s work centers Lilit, reviving the summoning practice that invoked her through a feminist, somatic portal to bring to our topsy-turvy time a wise and empathic Lilit, who, “finally has a smartphone” (see my text exchange with Lilit throughout this essay, or in full on page two).

At the opening for SUMMON, Tamar, charming and convivial, was wearing a cobalt blue velvet suit and orange turtleneck—orange like the wall of demon portraits that welcomed us, and blue-and-orange, which always brings to this poet’s mind Frank O’Hara, that color combo the New York poet’s favorite. O’Hara said of making (in his case, poems) “you just go on your nerve,”2 and this is so fitting, because in Tamar’s vivid, immediate-feeling depictions of otherworldly misfits, we see a raw and playful transmutation of nerves on the run. “It was when,” Tamar explains, “someone had a demon who was chasing them, that they would seek the aid of the artist-magician in capturing it.”

In more zeitgeist-ish terms, this sense of being pursued is akin to the activated sympathetic nervous system of the traumatized individual, someone no longer necessarily within the catalyzing terror but reliving it via the nervous system in fight-or-flight-or-freeze-or-fawn mode, obfuscating one’s ability to be present in their senses and reciprocal relationship—the locus of magic—with others. Explains meenadchi in Decolonizing Non-Violent Communication:

In this grand ole colonial culture, we are conditioned to glorify a fight response, to validate this strategy as the only ‘self-respecting’ form of defense. People who run away are cowards and those who remain passive or dissociate are often asked, ‘Why didn’t you do something?’ Even if others are not asking you this question, you may be asking yourself.

If you survived, YOU DID DO SOMETHING.” [emphasis theirs]3

Far from the exception, trauma is, per Bessel van der Kolk, a ubiquity, a spectrum, and an inheritance, echoic of ancestral wounds felt as far back as Babylon, inscribed, as if spelled out and cast within the torque of our double-helixed existence. Suggests Emanuel Coccia in Metamorphoses, “our DNA is a collection of ‘engrams’, hieroglyphics of all the battles, and especially the defeats, experienced by all those living beings whose will to redemption and salvation we embody.”4 In other terms, say French philosopher Emanuel Levinas’s, and paraphrased via Tamar’s somatics: “It’s not a question of anxiety, it’s a question of horror.”5 Tamar’s work holds this sense of vertiginous time knowingly and meets our current, vexed conditions with arch compassion and sacred profanity—in Tamar’s hands, these paradoxes are infused with curiosity and strange delight.

Tamar Ettun, Night Demon, 2023.

Tamar Ettun, Fire Tap, 2022. Courtesy the artist and Dreamsong.

Tamar Ettun, 66 Untitled (Lilit the Empathetic Demon), 2022. Courtesy the artist and Dreamsong.

Tamar Ettun, Blue and Orange Stitches Trap, 2022.

I felt drawn to the show by a drawing of one of the demons a friend shared in advance. A yellow birdlike creature uncannily twinned a being I had encountered in a meditation practice. That practice is known as “demon-feeding” per Lama Tsultrium Allione, as inspired by the wisdom of Machig Lapdrön, the 11th century female monk who, when confronted by demons, transformed herself into nectar and fed herself to them, which in turn, transformed them. Lama Tsultrim: “In some ways it sounds very counterintuitive. The last thing you want to do is feed your demons because that would make them bigger, but in fact our demons—and what I mean by demons is our fears and physical suffering, whatever it is that takes our energy—our demons gain strength when we fight them.”6

What moved me about this meditation practice is something that moves me about Tamar’s processes, the disarming task of inviting into manifestation that which has been hidden, denied, or lurking in our blind spots and affirming it. Recognizing this demon as depicted was to feel summoned to the show. Likewise, it makes sense, perhaps ancient sense, that the imagination—what William Blake called “the eternal body”7—has its own networks with ambassadors (angels/demons/extramoral messengers) to this material world from theirs.

In our first encounter, Tamar shared with me that Lilit came to her when she was at a residency, spending her days and nights in a haunted firehouse-turned-museum making knots and having just found out she was pregnant. That act of knotting haunted me, the material binding of looping back to move through the complex tangle of the moment one learns they are pregnant. The homophonic ghost of not-ness, making “not’s” to affirm what is emergent, in the no not, the knot to know. How many nots make a net? How far back does the thread go? What traces tell us so?

“The first track is the end of the string,” says Tom Brown in The Tracker, returning to a primal moment. “At the far end, a being is moving; a mystery, dropping a hint about itself every so many feet, telling you more about itself until you can almost see it, even before you come to it.”8 Tamar traces the knot: “And as you can see,” [pointing to Lilit as depicted in the Burney Relief], “she’s holding these ropes above her.”And in ritual: in some of the depictions of demons on the incantation bowls, we find them bound in ropes or chains (the most martial of knots), the spells inscribed around them.

In a curious 1930 essay on the knot in Hebrew literature published in the journal Isis, Solomon Gandz traces the early history of the knot as a proto-alphabet, “a beginning of the end,” the knot demonstrating “the zigzag way evolution took in the development of the alphabet.”9 In this sense, the incantation bowls depicted two forms of bondage—knots AND letters. Spelled out to spellbind. A friend tells me the Hebrew word for knot—kesher—is the word colloquially used to say keep in touch, i.e. let’s stay entangled.10 How we are bound to the other: pursuant, elusive, known, unknown.

In our subsequent correspondence, Tamar shared this from Totality and Infinity by aforementioned Levinas:

“To approach the other in conversation is to welcome his expression, in which at each instant he overflows the idea a thought would carry away from it. It is therefore to receive from the Other beyond the capacity of the I, which means exactly: to have the idea of infinity.”11

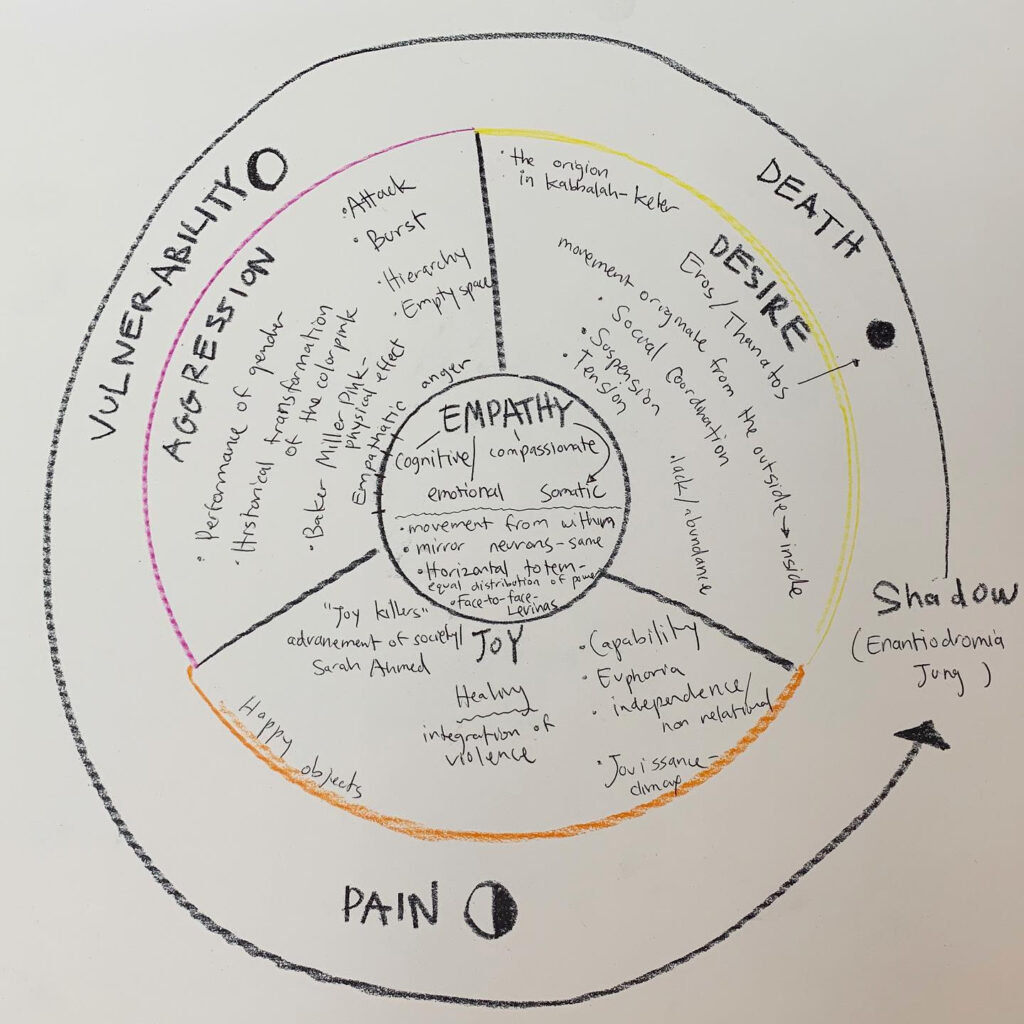

This access to the idea of infinity Levinas points to through the relational moment bears resonance in Tamar’s larger body of work, particularly with the Moving Company (under Tamar’s direction from 2013-2018)—a collective of artists focused on researching movement as an expression of empathy, still in operation today . Tamar explains, “What started as a hands-on research group in a residency in Abrons Art Center evolved to an active international performance ensemble which I directed.” Works like It’s Not a Question of Anxiety and Mauve Bird with Yellow Teeth Red Feathers Green Feet and a Rose Belly explore interdependence, horizontal totems, semiotics, and the somatic dimensions of empathy as distinct from emotional (I feel you), cognitive (I understand you), or compassionate (I feel called to action) empathy. Somatic empathy is a sensed movement from within, the body’s felt sense of another. In performance Tamar and her collaborators explored empathy’s interconnectedness. “So here”—Tamar says of a still from Part: BLUE of Mauve Bird—“tomatoes were held between the performers’ legs in a sculpture thinking about empathy as a support system. If one of the performers holds too hard or goes slack, the tomato falls.”

In Part: YELLOW of Mauve Bird, movers bound and framed in a giant infinity ream of fabric find ways to move in relation to each other to keep the fabric taut. Among them, two movers’ yellow costume is one—the two sharing very long sleeves that connect to each other. While Part: BLUE focused on empathy, Part: YELLOW focused on desire as an activating source, circulating within and between individuals and conditions. Mauve Bird invites a way of seeing both the murmuration and starling at once. While watching a video of Part: YELLOW being performed in Bryant Park, I began to see the bystanders and people moving behind the movers as a collective being too, an opening to the idea of infinity.

The Moving Company, Mauve Bird with Yellow Teeth Red Feathers Green Feet and a Rose Belly, Part: YELLOW, 2016.

The Moving Company, Mauve Bird with Yellow Teeth Red Feathers Green Feet and a Rose Belly, Part: BLUE, 2015-2018.

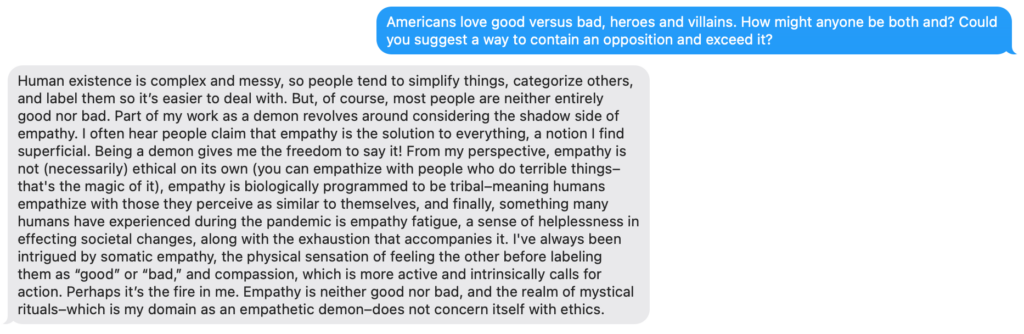

The Moving Company, Part: YELLOW, 2015-2018.

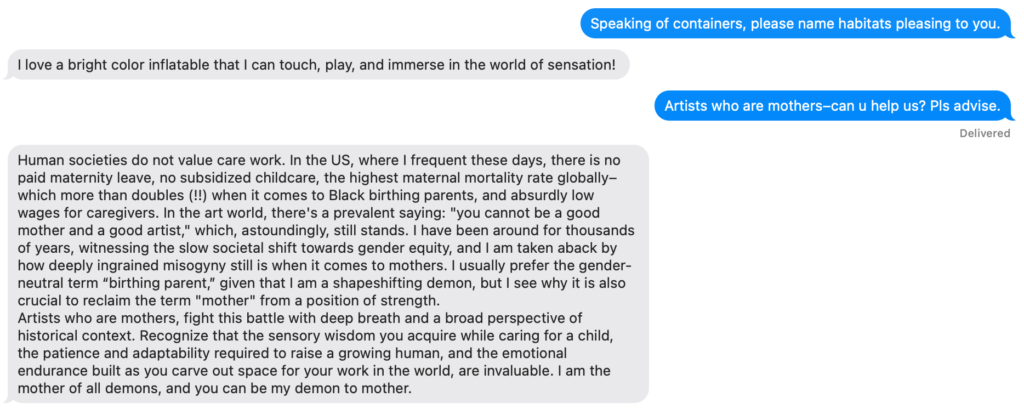

The Other without and the Other within. “It is therefore to receive from the Other beyond the capacity of the I, which means exactly: to have the idea of infinity.”12 It’s here, at this moment of overflow I want to return to Tamar’s demon portraits as they give expression (face/form/color) to the unseen and to Lilit as an empathic demon, as does Texts from Lilit, the enchanted deck capturing the images and texts Lilit sent to subscribers throughout the pandemic and continues to send (text SUMMON to Lilit at 833-575-1049 to subscribe.) Lilit’s texts speak with compassion to the collective trauma of the pandemic, including the correlation between being deprived of person-to-person encounters that Levinas speaks to, and the concurrent emergence of personal shadows in that void (I’ll speak for myself.) If it was not clear that the repressed had returned, there was a poster child in the White House for easy reference. As within so without.

In a masked artist talk at UC-Davis in October 2021, Tamar shared this from The Body Keeps the Score:

“Traumatized people chronically feel unsafe in their bodies: the past is alive in the form of a gnawing interior discomfort… In order to change, people need to become aware of their sensations and the way that their bodies interact with the world around them… When our senses become muffled, we no longer feel fully alive.”13

Tamar then asked: “I wonder if this is something that resonates with you right after this year and a half or almost two years of not being fully able to communicate or to move as freely and to go through a lot of anxiety and all this fear that we’re experiencing. How are we? What are our relationships to our senses these days?”14

Which brings us to the Inflatables, large-scale air-filled sculptures Tamar has been making since 2008, but hold a particular weight coming out of a time when the theft of breath by police state and virus filled our collective consciousness. Able to be encountered from both the outside and inside, their bold alien presence promises the transformation of perspective via “the sensory aim,” says Tamar, “being saturation.” Before art school, in mandatory service for the Israeli army, Tamar worked as an educator in a paratrooper unit , and initiated a mobile library on the base (she also left poems for soldiers on their pillows in the bunkhouse.) After art school, she spent a year apprenticing with a hot air balloonist. Tamar, who’s been an artist all her life, survived an orthodox upbringing thanks to art and libraries. “Art and libraries saved my life.”

In the bold simplicity and strangeness of the inflatables, you can see the conical shape of the very first hot air balloons; a flood of color as Tamar might have experienced when listening to the hue-based healing meditations her sisters with cystic fibrosis listened to at night; the magenta of desire; the magenta of doubt, of which her Rabbi grandfather suggested, there is no greater joy than doubt and there are doubts in finding it; the yellow of the shirt her painter grandmother dressed Tamar’s uncle in for first day of Yeshiva, an otherwise black and white affair. You can see lungs and wombs and collapsible monuments to inspiration, creaturely presence, the bloomsongs of demons, vivid vessels of healing, vivid from the Latin vividus, “to live.” To feel alive.

Tamar Ettun, Inflatables, 2015-ongoing.

Tamar Ettun, Lili and Lilu, 2015-ongoing. Photo: Daria Bishop.

Tamar Ettun, Wave Cave, 2022.

Tamar Ettun, Inflatables, 2015-ongoing.

Find the full text of the writer’s text exchange with Lilit on page two.

Tamar Ettun and Elisabeth Workman will be in conversation at Dreamsong on August 4, 2023. >>more information

Tamar Ettun’s installation and participatory performance Lilit the Empathic Demon will be presented at Free First Saturday on August 5, 2023 at the Walker Art Center. >>more information

Dreamsong will present Tamar Ettun at NADA House September 1-October 1, 2023, and at Armory Off-Site September 7-10, 2023. >>more information