The Burden of Proof

The Wisconsin Project looks into the myth and meaning of postcards (found, altered and invented) with questions about place, history and cultural identity: What is 'Middle America'? What really happened here, and how did we come to be this way?

Asking questions is risky business. As Doctor Zaius cautions George Taylor before he rides off into the sunset with his rifle and mute girlfriend in tow, you may not like what you find. But, risk or not, who among us is indifferent to the allure of knowing? Something doesn’t add up and we’re helpless to resist asking why. We need details: How exactly did this come to be? What really happened here? What is this place?

The Wisconsin Project, if nothing else, is the gateway to a lot of questions. It’s a web-based art project created by J. Shimon and J. Lindemann, two artists living and working in Appleton, Wisconsin. Looking through the site’s regionally-themed contents, you fall headfirst into every passing curiosity you’ve ever had about Wisconsin — particularly if you hail from anywhere nearby (just across the St. Croix in my case). By way of this sprawling online resource, the two artists are effectively wandering, open-eyed into their own backyard, asking questions of everything they find there and inviting you, the viewer, to do the same.

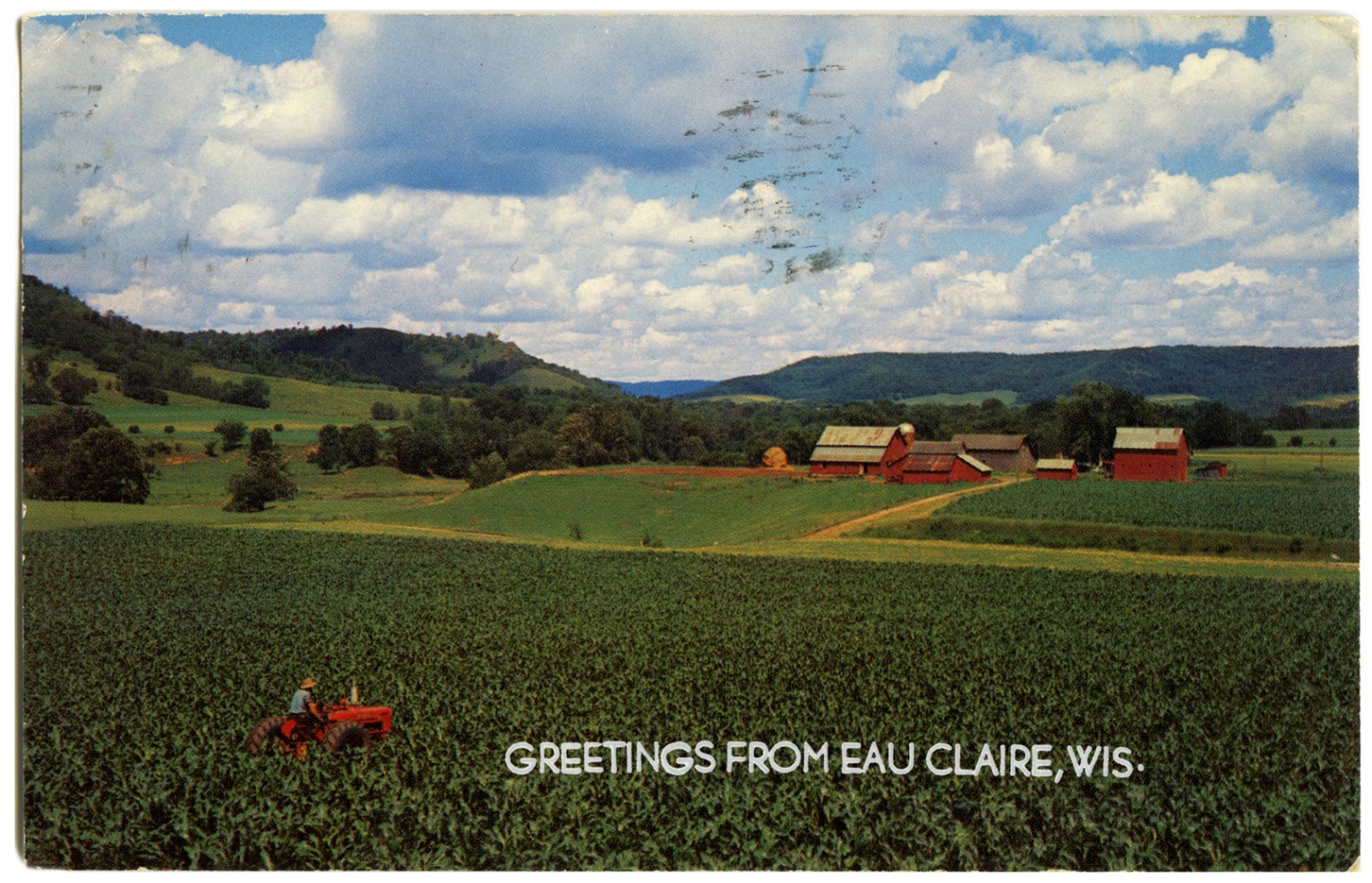

As a starting point, the project examines postcards as a kind of shorthand for Wisconsin’s image of itself; as such, the cards’ representations of place and history are laden with reflexive significance. The postcards range in time from the 19th century to today and depict the state’s shopping malls, forests, town streets and tourist destinations. Shimon and Lindemann often travel to the places depicted in the vintage postcards to follow up on what’s become of the sites featured. The two artists also create new postcard images from their travels using vintage photographic equipment; their newly made shots tend to follow the aesthetic example of postcards from the past, to engage them in a kind of visual conversation.

“Ultimately,” Shimon and Lindemann say on their site, “we aim to grapple with complex perceptions of Wisconsin ranging from nostalgic, romantic, and idealized–as depicted on myriad real photo postcards and standard tourist postcards — to mysterious, dark, and Gothic as conveyed in works of art and literature.”

The postcard, of course, with its miniaturized, snapshot view, has its own syntax and grammar. What’s written in and on postcards is always and, perhaps, inevitably false — sentimental confabulations of time and place, from the image on the front to the missive penned on back. (Interestingly, Shimon and Lindemann report that an inordinate number of postcards are inscribed with a brief apology for not having written sooner.) The world depicted on a postcard is of necessity a set piece, a staged, pre-nostalgic memento of a time that never happened sent from a place that never really existed.

The postcard is a social tic, a pathology of memory born of hope and desire incompletely understood even at the time of its creation and dissemination. Postcards commemorate banal and lonely landscapes as often as they do fun and lively worlds, but both show the preoccupations, assumptions and blind spots of the time and place from which they originate. And that’s where things get particularly interesting.

Shimon and Lindemann are very much aware of the complications and problems that can arise from digging into the past, particularly from close looking at popular representations of history. In fact, it seems likely one of the reasons they began the project was precisely to examine these complications, to show the tumult of contradiction and conflict beneath the deceptively placid surface of Wisconsin’s idea of itself.

Take the annual summer festival of Symco, Wisconsin, for instance: each year, the town celebrates the warmer months by recreating a summer’s day, circa 1964. On its face, such a thing sounds delightfully nostalgic, like a community-wide re-enactment of some upbeat episode of The Twilight Zone. That is, it sounds good as long as you’re seeing that time through the lens of white men’s experience — for everyone else, that time in history wasn’t quite so rosy.

Or consider this: a number of the Wisconsin Project’s souvenir postcards feature representations of Native Americans, both actual indigenous people and actors playing the part; regardless, the clothing and poses in the postcards are always the product of a Disneyfied, 1950s American imagination. Just the same, one such postcard features the Indian Bowl, a roadside attraction operated by the Lac du Flambeau Tribe of Lake Superior Chippewa (which has, according to its website, “presented traditional Ojibwe dance, powwows and cultural events since 1951”). The tribe has run the place all these years, at least in part, to cater to white tourist dollars such destination spots draw to the area. This sort of contradiction — a cultural history which survives in part because of a selective (and often just false) rendering of the same — is at the heart of Shimon and Lindemann’s project.

The collection as a whole asks us to suspend judgment, to look closely at the narratives represented by the images and text of Wisconsin’s postcards. Presented this way, the postcards tell us stories about who made them, of course, but they’re liable to reveal just as much about us, the people reading them now.

The Wisconsin Project was featured in a recent exhibit at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan. The exhibition title, We Go From What We Know, served at once as a mission statement, a warning, and an apology. After all, we all have to start somewhere. We start in the world that forms us, whose tastes and sounds we know from childhood. We don’t get to choose the culture we are born into and yet, that culture is no more or less than us. And by the same token, we are always in the fold, whether we ultimately embrace or disregard the cultural particulars with which we’re raised.

Artists as talented as these two might head to New York City, the big wide world of art, someplace far away from the kitschy postcards of America’s Dairyland. It’s all the more interesting that the Wisconsin Project and We Go From What We Know represents the choice to remain, to turn the lens close to home.

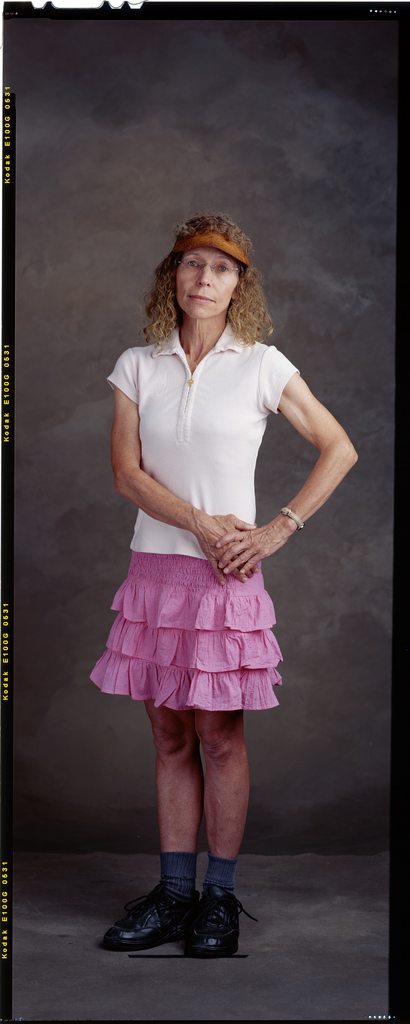

The exhibition included a large sampling of postcards, of course, as well as a fairly literal, close-up look at the Badger State in the form of life-size images of Wisconsin’s natives and tourists. The centerpiece of the gallery show was a 1949, Wisconsin-made Nash automobile filled with concrete corn cobs. Quite unlike the light, airy things that real corn cobs are, easily broken down by a harsh Wisconsin winter, the stone cobs appeared more as a heavy shadow of the past, overburdening and spilling out of the open car.

______________________________________________________

By looking closely at these generally overlooked corners of the workaday world, these subtle images capture the most intimate, honest parts of our public selves — like close-ups of elbows and toes, they’re examining the working parts of our social being.

______________________________________________________

In addition to the project’s own postcards, the gallery invited visitors to add still more, to contribute to the exhibit. That’s another trope of the project, this emphasis on open-ended collaboration. The Wisconsin Project at large includes a standing invitation for anyone to join in by submitting postcards, found or made, of their own. Of course, when an entire state’s cultural identity forms the basis of one’s project, it only makes sense to invite other residents to participate. To facilitate such engagement, Shimon and Lindemann hold workshops in which participants are encouraged to alter vintage postcards “using watercolors, erasure, markers and collage to add a contemporary commentary on place,” to take these specific and received images of the past and change them. In so doing, the artists are also inviting their fellow Wisconsinites to change history, or at least change what it means.

Given the heavy rotation of exoticized Native American tropes in the postcards, for example, I’d be interested to see what artist Jim Denomie (originally from Wisconsin) would do with some of the project’s images (as I’m sure would Shimon and Lindemann). The idea of giving contemporary treatments to historical representations of our world reminds me very much of what Valerie Hagerty recently did to some of the period rooms at the Brooklyn Museum. This insistence on not just examining images of the past but also intervening and changing them actually brings history to life in new ways; the act of engaging the past in that way reinforces a sense of connection, continuity with what has come before. Surely, this is one of the central aims of the Wisconsin Project.

As noted above, Shimon and Lindemann also create new postcard-like scenes of their own using vintage photographic equipment: images of rural homes, small town streets and local attractions — many of the same subjects of classic postcards. The duo’s made photographs are not striking. The framing’s always simple; they are monochrome. While I missed some of the gaudiness and the vibrant colors characteristic of vintage postcards, the restrained mode of postcard photography Shimon and Lindemann choose — the intentionally plain presentation of their subjects — provides an intriguing foil for the more sentimentalized images in the collection.

Their work reminds me of the sort of work featured in Phaidon’s Boring Postcards, USA — full of highway overpasses and corporate headquarters. But despite the apparently banal subject matter, even these contain the presumptions and preoccupations of the postcard form. Even these unlovely shots reveal how we live our lives, where we derive our sense of identity. These postcards say: Look at my trailer home. Look at my strip mall. Look my freeway exit. In the act of looking closely at these generally overlooked corners of the workaday world, these subtle images capture the most intimate, honest parts of our public selves. Like close-ups of elbows and toes, they’re examining the working parts of our social being.

Looking through the Wisconsin Project website, with its pow-wows and small town intersections, it’s hard not to jump to a perhaps predictable conclusion, that the artists are ultimately getting at something like: We live in Hicksville, but ain’t it grand? That’s hardly the sum of it, of course. Hicksville or not, this place – not just Wisconsin, but the whole of the Midwest – is filled with people just doing the things that people do everywhere, and we ignore the contours and contributions of their lives at our peril. What the project shows, in understated but vivid terms, is how a place like Wisconsin, anyplace really, is clotted with human drama and intrigue.

Whatever art-with-a-capital-A is pursuing, surely its work is, like any human endeavor, informed by emotion and personal history — those things exist in abundance no matter where we are. And if we don’t investigate where we come from, try to get inside that history, we are less likely to understand where we are, much less where we are going.

“Looking carefully and attentively into a single small aspect of the world, we believe, can provide more insight into the human condition than searching the world over,” Shimon says. It would be fascinating if other artists committed to similar projects, so that we could wander through their backyards, too.

Related links:

Explore the Wisconsin Project online: http://wisconsinproject.blogspot.com/

Jay Orff is a writer living in Minneapolis. His writing has appeared in Rain Taxi, Reed and Harper’s.