Objects Talk, Spirits Talk, Ghosts Talk, Beings Talk: A Conversation with BakiBakiBaki

Materiality, memory, and creating a space of being-with in Reclaim Your Divinity

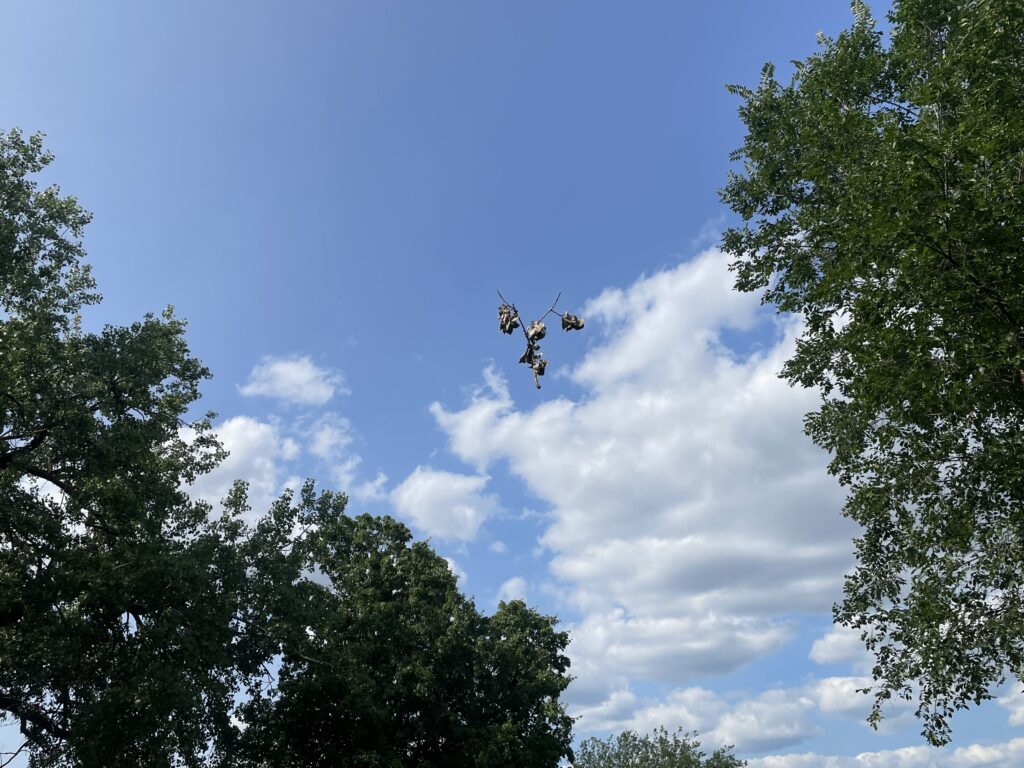

Between the limbs of two trees in Powderhorn Park, a forked branch balanced on a barely visible line of string.

The limb appears to dance in midair. Dried, curled leaves on the branch waver like quietly laughing, hollow-eyed faces. In the middle of my conversation with Minneapolis Northsider and multipurpose artist BakiBakiBaki, we sat, encountering the branch’s strange and liminal presence.

“Is it hung up by so many spiderwebs?” BakiBakiBaki suggested. That seemed likely, and anything felt possible. The presence of the dangling branch entranced us both and made our conversation about BakiBakiBaki’s solo exhibition visible, emblematic, and surreal. The branch was secure in its distance from other leaves, suspended in the sky.

Reclaim Your Divinity, at the Creating Change Gallery in Midtown Global Market runs until August 2, 2024. The multi-media art installation, in keeping with BakiBakiBaki’s multipurpose artistic practice as a poet, collage artist, and trickster spirit, is arranged as an altar space that features mirrors adorned with emblems and images that are both caustic and sacred. The gallery exhibit’s objects and iconographic conversations with ghosts uplift the artist’s lived experiences as a Black and Native person.

As a non-Black Indian immigrant who has lived my entire adult life in Minneapolis, my experiences of this city have been shaped by the reality of institutionalized anti-Black and anti-Indigenous violence. This is the reality of anyone living in the US–that our orientation towards this land and towards each other are informed by the ongoing legacies of settler colonialism, genocide, and enslavement. A simple liberal approach elides these histories and instead leans towards a narrative of progress, obscuring the lived experiences of Black and Native artists into superficial and consumptive sites of healing-as-in-moving-on. In contrast, BakiBakiBaki’s demanding and ineffable work stages a non-reparative space of holding ongoing racist trauma that draws all forms of meaning-making into itself. State violence, spectacle, and Spirit are equally invoked to provoke a space of being-with, not refusing or looking anxiously for a way out.

By staging a variety of objects emblazoned with images such as a noose, a gun, a cross, and a torch, BakiBakiBaki asks viewers to consider, for a moment, that all of history is in the room with us. It has always been in the room with us.

BakiBakiBaki’s work is evocative of Black poet and visual artist Krista Franklin, who contends with a simultaneity of materiality and memory in her poetic and collagist works. In her poem “Marie Says Bow Down,” that considers how time marks the human and the human marks time, Franklin writes: “I need you to remember with me / … What year is this? Do you know / how long the cops have been called? / My love, before there were even phones.”

Likewise, the show Reclaim Your Divinity conjures, surfacing what already exists, into the gallery space. By staging a variety of objects emblazoned with images such as a noose, a gun, a cross, and a torch, BakiBakiBaki asks viewers to consider, for a moment, that all of history is in the room with us. It has always been in the room with us. Our intersecting and incomplete stories, ancestry, and pasts live in our sacred spaces, in our intimate relationships, in our nightstands and in our mirrors and bloodlines. Reclaim Your Divinity asks, “what spirits make themselves visible when we give in to that invitation, of spending time with our tenderness and giving over to our sorrow and our anger?”

A branch of open-eyed leaf faces shiver against a bright blue sky.

“Being a poet has helped me stay out of an institution,” BakiBakiBaki reflects, “All I know is that when I feel like I have nothing, I have puppets and collages and poems.”

I had the pleasure of speaking with BakiBakiBaki about their show. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

FAITH & MATERIAL

Aegor RayI want to talk to you about your relationship to church spaces, to Christianity, and to the Christian animism that you invoke through altars and stained glass–posing the present and the past together. With your show titled Reclaim Your Divinity, I’m curious about what I see as jubilant decoration as a mode of claiming your own story and relationship to faith.

BAkibakibakiI think I’m forever going to be a church kid, I can’t escape that. I’ve always had this obsession with inquiry that helps me connect salvation, what I thought I was condemned from as a queer person, with what I see as the most sacred thing–Mother Nature and her materiality.

That’s why I love altars, right? People look at a table and they’re like, “okay, cool, a table.” And then I’m like, “Do you know the history of a table? Do you understand?” I believe the wood, and the tree that made this wood for this table, is still alive and energy is embedded into it. And what that means is that this table sees every meal that you consume, every tear you cry.

I was recently talking to a friend of mine who also has artistic parents, and I was like, “I don’t know if anything I do is original.” Growing up in our North Minneapolis home, there were all these tiny small windows that just barely met the fire requirements. And my mom was like, “How do I decorate these?” She always loved old Victorian homes and was a good Catholic girl at one point and just researched and just was very fond of stained-glass windows and the history of them. I just witnessed her, and there’s actually this chemical compound that comes in tubes that dries to mimic stained-glass. She used that to transform our windows into these beautiful renditions of peacock feathers.

I was reminded of the church space when I was a little girl and wore white pantyhose with pride, I could ask questions all the time. And adults would open up the Bible and show me that Jesus’s words be childlike. And so I was like, “hold up now. It’s not me shifting or questioning you have a problem with, and tricks aren’t necessarily bad.” And then I learned about Ananse, the spider, as well as other tricksters such as the coyote. This quality I have–of shapeshifting, moving between material and story–that’s a gift, that is often beautiful inherently, even as people might see it in the context of manipulation or degradation. I’ve always been decorating and destroying.

When I pray, I let my teenager self speak. And teenager Jesus comes to me and hangs out with me and tells me things. They told me that they feel if I had a thesis statement to this piece, it would be that the cross is a tool of state violence, and should be treated as such. That’s the context of it. And I feel everything happening at the same time, how I am and how I came to be. So, while I’m alive and able to walk down the street pretty much as a free agent, as a free self, my enslaved ancestors are on the plantation praying for their safety and mine at the same time. So when I’m in this lovely meadow of lavender and daffodils and sunflowers and dandelions and my teenage self is praying in my safe space, Jesus comes and visits me. Because it’s just one hop skip over from the plantations they visit of my ancestors.

Sometimes my mother be scared about this, and I’ve learned about how many people are either institutionalized or try to manipulate others when they say that Jesus talks to them. But everyday Christianity is used as a colonization and shaming tool by asking people, “What would Jesus do?” Well, my artistic ass took that shit literally. And brought it into my home, into my context.

MEMORY AND ALTERITY

ARCan you tell me about the iconography you depict in your pieces? How did it come to you and how do you see the iconographic expression conveying meaning in your show?

BBBThe stained glass mirrors in my show depict nooses, guns, crosses, and torches.

There’s one piece that is a mirror that is structured, with decorations of flowers in the metal. My mom helped me get these mirrors from Goodwill, and when I prayed with this mirror, I realized there was a white woman colonizer spirit trapped in this mirror. So, I would have all my friends come visit the studio and have queer people just look at themselves in the mirror and clean the mirror with Florida water. And then I would talk to her.

I felt that this conversation with the colonizer spirit–creative process, whatever you want to call it–was like engaging with the shadow side of Spirit. I am Indigenous and of African descent, but I know that my Self is funneled through American colonization. As a Black American, I can’t separate myself from that reality–nor do I want to.

When I drew the noose onto this mirror, this white woman in this mirror spirit was uncomfortable. She felt like, “people are going to look at me and see me as an enslaver.” And I was like, “that’s kind of the point.” I was like, “Are you worried that people are going to look at you with disgust?” And she was like, “Yes.” And I was like, “Why are you one bound to this mirror?”

I purposefully placed images over and over. There’s two guns, there’s two nooses, there’s one cross, and one torch in the show. There’s a church window that has beaded work keeping in mind both African and Turtle Island indigeneity practices. Lots of beadwork and repetition in these mirrors.

ARWhat stories do you want people to contend with in this show?

BBBSo many Minnesotans seem to be like, “Our whole world changed with 2020.” And as a Black American, as a Black Minnesotan, as a Northsider, my life was transformed with Jamar Clark’s lynching in 2015.

Do you know how many Northsiders still have trauma from being shot at by off-duty police officers? I feel like there’s so many other Black activists who are scared to bring up Jamar Clark or Philando Castile when we’re talking about George Floyd. For my practice, creatively and in community, I have to believe that these uncles are drinking and smoking together right now. And ushering every baby that comes in next.

What I’m learning is part of the Black and Hoodoo experience. Knowing when and how to share those things without being prophesied or turned into a monster yourself. Knowing what spaces are safe to really be like, “I hear things, I see things, I feel things.” I say this all confidently. Knowing that Christianity itself is an amalgamation of stolen stories from Edwina who first wrote about the deity Inanna–who went to the underworld before Jesus. Inanna is an intersex goddess who comes from Sumerian times, and her temples were for transgender folks, and sex workers.

ARFor me, myths of beings going to the underworld reflect that we need those people who can hear the voices for the rest of us, and that it’s like a huge charge and burden to hold.

I am interested in how you identify yourself in your practice. I’m also interested in the way that you to bring in violent images from our ongoing history into sacred spaces. It’s such a disruption of what we hold to be sacred and also what we allow ourselves to hold.

The gun is in the room whether or not anyone mentions it. And so, you made it plain, and there’s something about that that is scary to confront, but there’s a greater safety in like allowing art to be the channel for that experience.

BBBWell, I think the underworld is humanity’s and colonization’s reduction of decomposition.

For my art practice, I’ll say multidimensional, but something that I’m really obsessed with right now is multipurpose. I’m a multipurpose artist, because I have many intentions and I think every material I come into contact with has a life purpose. Chai has a purpose. When I drink it, I embody it. Tables have a purpose. So, I’m a multipurpose artist is what I like to say the most. Because I’m incorporating what I work with. I’m metabolizing. There’s no reclaiming, really, just embodying. Hey, do you see how that tree limb looks like it’s just floating in the air?

BakiBakiBaki’s solo exhibition Reclaim Your Divinity is on view at Creating Change Gallery in the Midtown Global Market through August 2, 2024. The gallery is open Tuesdays and Thursdays from 2-5 PM.