Curator to Curator: Reflecting on Saturday Mornings and The Faces We Remember

Incoming guest editor Za'Nia Coleman in conversation with Walker Art Center assistant curator Taylor Jasper: activating spaces, centering community, and building a curatorial practice

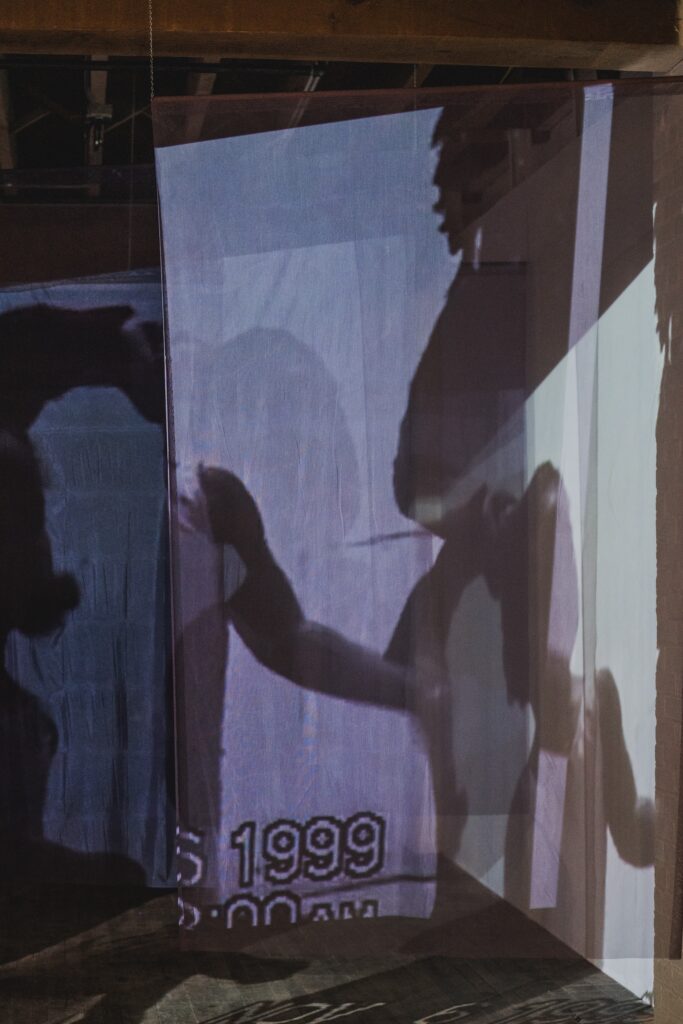

Za'nia colemanFor full context, this was my first solo exhibition and it was done as the final part of my fellowship with ECI, Emerging Curators Institute. It was also my first formal curatorial project. As my project with ECI evolved over time, I struggled to grasp the approach of having a theme, asking artists for work, and then organizing a show around that theme. It just wasn’t connecting for me. I was really interested in archives, and it just so happened that my childhood dance studio needed someone to digitize their old VHS tapes. I thought, if Ms. Diana [the studio owner and instructor] would let me do it, I would love to base my project on her and the studio. The old footage, photos, and the fact that the physical space and community were still intact made it a perfect opportunity.

I consider the project an ode to my childhood and to community spaces like that, which are often affected by gentrification. These spaces are changing, new people are moving in, and the environment is altering. This project is a way to honor Ms. Diana and the work of Hollywood Studio of Dance, as well as the people who have passed through that space. It represents the history for those new to the community.

Taylor JasperI think one thing that I really loved about the show is that when we think about the archive, about history more generally and historical silences, emissions, erasures, all of that is a reflection of the record, which means that the written record and the archive to me are really what constitute historical narratives. That’s the proof. We know that’s not the case, that there are other ways for knowledge to be produced and reconstructed and disseminated orally, socially, relationally, but in the West, we privilege the written word. I think what was really great about this project is that often, especially in the Black community, we hear about our social spaces and our spaces that are no longer here anecdotally. We hear the stories about the barbershop that everybody used to go to, but there’s no record of that place existing. If it isn’t archived or if it doesn’t constitute a history in that way.

Engaging also with a more recent history, because I think generally people think of history in the archive as something that happened long ago or something that’s detached, is really great and really meaningful. I would be really interested to know, I think you were talking a little bit about the kind of quilting points between your artistic practice and this curatorial project–was that something that you were consciously aware of, this kind of artist curator positionality? Did this feel like a creative… You know what I mean? Does your creative work feel separate from this kind of curatorial work, or is there an intersection between the two?

ZCI’ve been calling myself an interdisciplinary artist since I can remember. I don’t actually think I knew what that meant. It felt very anecdotal. It was just like, what do you do? I’m an interdisciplinary artist. I think two weeks out from the show opening, I really understood what I was doing, which was late considering how much needed to get done. It really became, not stressful, but hard to hold just being an artist and making something and putting it out to the world, and then having the task of then being a curator, which I think is a little bit more heavy-handed on how that work is shown and engaged with. So trying to find the balance between making a creative decision but then it’s like as a curator, how much of it is my responsibility to communicate what that thing is?

So it’s over explaining, being heavy-handed with it, but then letting the audience feel what they want to feel. It’s like where did the lines end for the artists and the curator? Two weeks out, I was really seeing, and I would’ve definitely loved to have done my timeline different. Whereas finishing the work, the archive was one thing, the representing of the archive and some of the more creative aspects, and then the curating in the actual space, it was all three different things. So two weeks out, it was crunch time to figure out which pieces I wasn’t going to get to do in all those areas.

TJThat’s really interesting. Not only are you trying to create context for work in a show when you’re exhibition making, you have to reflect on it at the same time, and that’s really difficult. It’s like, how do I reflect on the work? How do I present the work? How do I contextualize the work, and ultimately how will people view and interpret the work? Those to me are my guiding questions or my guideposts through the exhibition-making process. I wonder, did you feel that same tension as well? How do I create the context and do the thing at the same time?

ZCI was glad I had so much time to be in this space because from a curatorial standpoint, that is actually where the work starts. Once you get in this space, it’s like, this is actually what I have to work with. Through ECI we had the option of five or six different galleries, and Public Functionary was my first pick solely because of the relationships I have with the staff and the folx that work over there.

I think because of that, I felt very grateful. Everyone knew me personally, so it was nice to have familiar people guiding me through it. I thought, “This would’ve been rough for people who didn’t know me. Really rough.” Two weeks out, I went there for the first time. They were between exhibitions, so the space was empty with just a rug on the floor. I would sit on the floor, go through some photos, and just be in that space. I thought, “Wow, I would’ve picked a smaller space. This is a lot.”

Visually, that minimalist approach has always been what I associate with art. So, when thinking about my show, I still thought about space in that way. I considered how space could be used to let things breathe and how much text I needed to include. Text can make things look jumbled and cluttered, and I wondered if people would still get the message if they didn’t read it. So, it was interesting to figure all of that out–how to engage with spaces, how to present things so they’re understood, and how to balance space and text.

TJI’m just really hearing what you’re saying about the white cube feeling very inaccessible. I don’t think people really think of being a curator as also negotiating spatial relationships in that way. It is like, how do works relate to each other on a wall, the kind of archaic view of the curator of “hang this here, hang this there,” but it’s like when you actually spend time in space, like I was telling you earlier, I walked a floor plan I’ve been working on for months and was like, oh my God, it doesn’t work. Once you’re in the space and you see the way that people move through a space, it can have such an impact, but also can be a barrier.

So also thinking about the way that people negotiate space, does it make sense to create a choreography within an exhibition or an engineered route through it? Then all of those things feed, like you were saying, the interpretation. How much do I write? How much context do I give? I think one thing that I also loved about the show was how I felt like it was very, very multimedia and sometimes shows that center archives can amount to a series of papers in vitrines [collective laughter] or images in vitrines, and so it was really awesome, I think, and spoke back to the fact that you were talking about a dance studio, that this space was activated by so many different types of media.

ZCBeing interdisciplinary, I studied film with a focus on documentary, and my first job was as an oral historian. Over the years, my film projects have always taken a long time to complete, from the initial idea to showing it to the world. One of the first times everything came together was when I focused on integrating moving images into my documentary work. Archives have often been my subject matter, as they are foundational for documentary work. This time, I was intentional about incorporating moving images into my artistic practice in a way that wasn’t cumbersome but still told compelling stories. I wanted viewers to feel immersed in the visuals.

In the space, I didn’t notice some of the creative choices until others pointed them out to me. A lot of them felt instinctive rather than overly planned. I wanted to incorporate elements that aligned with the dance studio and the subject matter without overshadowing the archive. Things needed to be clear and visible. One of the key discussions I had was about balancing abstraction with literal representation. How much can I abstract an image before it becomes unrecognizable? That’s not the goal of archival work; people should know what they’re seeing. It was about finding that sweet spot where the visuals are engaging but still clearly convey [collective laughter] the archival content.

TJI wanted to ask a little bit about something, which we talked about a lot with the Walker audiences. The Sadie Barnett project is a perfect example of it. That project was about creating a space, a Black queer space within the context of a museum, and not only a Black queer space, but a Black queer social space. So in order to do that, you need Black queer people to view it [collective laughter], and so how do we get Black queer folks who are my community into the building, which is a point of pride for me. I think we did that.

If I may say, but also wanted to know, was that something you took into consideration? Who is this for, or is it for everybody? Is it for anybody? I feel that there is a very specific difference between those two things, but yeah, just how did you conceptualize or consider audience?

ZCI think that was also another bucket that I realized was a bucket around week two out from the show.

TJThis two weeks was wild.

ZCWhen you think about it, it’s like the archive, curating, being the artist, and then the work of getting the right people in the space, those are all very different tasks.

TJFor sure.

ZCI knew this was for, and still the intended audience is, for little Black girls to see themselves in a space like that, memorialized in that way, where the fact that you were here matters, even if you come back and the studio’s gone. You know what I mean?

TJRight.

ZCI would’ve needed a lot more time to engage that audience, to get dance troops in, contact other dance studios in the city and build relationships with the instructors and have folks to feel comfortable and interested in engaging with the exhibition… Visiting the studio also inspired the name for my project. Most people remember going to class on Saturday mornings, and my interest in the photos stemmed from recognizing familiar faces. As people get older, they might not remember the dances, but they’ll remember the faces. For Black folks, Sunday was typically for church, while Saturday morning was for dance class. This felt like a clear identifier for my project. I wanted a title that resonated with my audience and wasn’t too abstract.

TJ[collective laughter] It’s a lot to negotiate, a lot to hold and a lot to mediate between, I think as a curator and especially some overlap between our curatorial practices because we’ve talked about, in my view, there are many different types of curator, but there are a few in my mind that stand out or there’s a curator who’s a librarian of the objects under her care. Who’s here to hold work and present it, and then thinking of a museum in a library in that type of way. There are celebrity curators. There are curators who are really into relationality, which I think is a way that I would position myself and being in community. There are curators who are highly academic and are more art historical in their approach, Multiple Realities, I think, is a great example of that. Identifying periods that are underrepresented in the canon and bringing those to the fore. There are all types of different ways to curate and different things to think about. One thing we both share in the work is what actually guides that process.

The work and the artists, which in this case would be like the studio and Ms. Diane, guide the process, guide the exhibition making. It’s not necessarily about finding objects that narrate or visualize a certain narrative or thesis that you’re trying to demonstrate or developing a thesis around patterns that you see in work that you encounter, but encountering work and letting that work speak. I think it’s really interesting what you were saying about those two titles because I think I am feeling also a similarity between working with living artists, especially emerging artists whose practices are developing and ongoing, where I’m looking at a period in this artist’s practice or I’m looking at a specific body of work.

ZCWhat that makes me think about is when you have those types of spaces, I’m interested in how for your own practice, when it comes to the balance between authorship over this space in dictating what the narrative is, because I feel like as an artist, sometimes you’re meant to let people interpret. One thing I remember you saying about being a curator is curating what the conversation is around the work. What’s your process for striking the balance between letting work breathe, and not over articulation [laughter], but guiding people’s thoughts of this is what we are thinking about?

TJYeah, no, this is very present in my mind. I was just talking about it this morning because I do not like the formalist approach to looking at art, like blue means this, the red curtain means that, the “this equals that” logic of making or understanding work. I think my goal as a curator is I want everyone to feel empowered in their own experience of the work that they are viewing, and looking at a work that is a red dot on a white canvas and not understanding is your experience of the work and that’s valid, and empowering people to feel comfortable in that, in that discomfort or that not knowing or thinking of art as a way of knowing I think is really important to me.

I’m a curator who’s not super into heavy interpretation or writing, and part of that is visual. Like you said, labels can really ground. I think it is important to give room to breathe, but I’m also really interested in creating spaces for reflection and critical dialogue within the exhibition space. I’ve been thinking about it for this Kandis Williams project, creating a reading group or discussion groups about exhibitions so people have a forum to discuss what they feel like they’re seeing or coming to know and facilitating that in that way. I think any reaction, any emotional response is understanding, is totally valid, and I want people to be comfortable in that. That’s kind of how I think about negotiating authorship in that way.

ZCAre there things as a curator in the field that you’re interested in being cultivated or new things you’re excited to see?

TJI think the curatorial field is highly academic and highly professionalized, highly professional. I would love to see the position of the curator just continue to be negotiated and renegotiated in a way that democratizes the field. As I’ve told you, I don’t have a master’s degree, I don’t have a PhD, and that is somewhat rare, frankly. I’m not saying that as if anything about me. I’m really saying it more about institutions and their hiring practices and the extreme barriers to entry that exist in this field. I remember actually when I was wanting to enter the curatorial field coming upon the ECI website somehow, and just being like, I wish that more alternative pathways like ECI existed because, personally, the way that I curate is not taught in schools.

There is not a degree that I feel would help me be any better a curator than I already am, and I want more people to know that, and I want more people to be able to access the field and also know that you can engage with the curatorial and not be a “curator.” I think about the way that my grandma used to have this beautiful china cabinet that was like so wonderfully… photos, trinkets, china. There was everything in this china cabinet, and it was gorgeous. I mean, that’s curatorial. That’s curating. I think that especially as Black folk, again, we have ways of knowing that are not considered academic or are not considered legitimate, that still lend themselves to curatorial work, and that’s valid and great, and that’s what I hope continues to be more the case and beyond just Black folk. This time, actually everybody. [collective laughter].

ZCThat felt good.

TJThat felt good, I think. We’ve definitely got some good stuff.