Reads Dylan Hicks

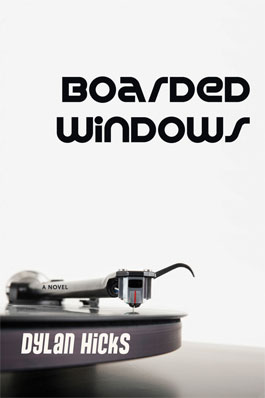

Writer Jay Orff reviews Dylan Hicks's new novel, "Boarded Windows," an engaging tangle of competing stories and unreliable narrators with its own soundtrack (the accompanying new album "Sings Bolling Greene"), written by musician and writer Dylan Hicks.

IT’S NOT MUCH OF A SPOILER TO REVEAL that the titular boarded windows of Dylan Hicks’s new novel refer, specifically, to windows that have been boarded over as part of a movie set created by some amateur filmmakers. The windows aren’t even really boarded over; they’re just a prop in a story someone is telling. And this novel is obsessed with, among other things, the ways we use storytelling to create ourselves and meaning in our world.

Boarded Windows, a funny, intelligent, self-effacing novel, is told through the voice of one would-be storyteller in particular, an unnamed narrator who is writing his own story, struggling to be as accurate as possible in order to try to understand that tale he is (re)telling and how it has formed who he is.

The events in the book focus on three periods in the narrator’s life: when he was a kid, growing up in the mythical North Dakota town of Enswell (strikingly similar to Minot, but more on that later); his young adulthood in Minneapolis; and the time of the story’s telling, more or less the present. These time periods are chosen because they are the moments when the lives of the narrator and his father figure, Wade Salem, intersect. It is possible, although denied by all involved, that Wade is the narrator’s actual biological father. Regardless of the particulars of their relationship, it’s clear that Wade is as close as the narrator will get to a father; when the narrator is a kid he even briefly calls Wade his “step-dad.” Unusually, the narrator can’t be absolutely certain who his mother is either; as with determining his father’s identity, he has only the stories people tell him to go on. Every aspect of the narrator’s lineage is confused and blurred in competing narratives.

And the novel is carnival ride of amusing, sad narratives — people talking about last night and about ten years ago; people retelling familiar stories and shocking, new ones; people talking about their favorite philosophers and favorite country albums — the book is made up of people telling people the stories of their lives. What seems to be key, for the narrator certainly, is deciding which of these stories to believe. The problem, of course, lies in determining how and where the source material has been polluted, corrupted, and distorted through time. The narrator assures us he is trying to avoid such corruption in the narrative he is creating, but he also confesses to us that he can’t remember certain things, that he’s tempted to change details here and there to make himself sound more interesting.

Basically, the narrator of Boarded Windows is concerned with the sorts of decisions a writer makes at every word: What is this world I am making up, how does it work, and what does it mean? A central project of Hicks’s book, I think, is to show how constructing an accurate narrative of reality is only ever going to be narrowly successful (which, in this novel, is a lot more fun and a lot funnier than that summation may sound).

There are artifacts throughout the novel which serve as evidence of the deleterious effects of time and repetition — a book is reprinted in an inferior edition with illustrations missing, a copy of a copy of a set list gets crooked, cassettes of favorite LPs decay to unlistenability. Our attempts to preserve the truth of the past fail. And all of the characters’ competing stories are told through the idiosyncratic filters of private emotional truths, rather than by a dispassionate accounting of what may or may not have happened. Each day is further and further removed from the past, from the original event the novel’s narrator is trying to get back to and understand — even that originating point may not exist as such, not even in that unreachable past. Even then, the world was/is made up of conflicting narratives. It’s fitting, then, that in the novel we hear about the break up of Wade and Marleen Deskin, the narrator’s “mother,” but hear a different version of how it happened from each person who tells the story.

______________________________________________________

The novel is carnival ride of amusing, sad narratives — people telling people the stories of their lives. The problem lies in deciding which of these many stories to believe, determining how and where the source material has been polluted, corrupted, and distorted through time.

______________________________________________________

WADE SALEM IS THE NOVEL’S STAR and a master storyteller. Most of his stories are, ultimately, about himself but he works in references to Wittgenstein, Rilke, Charles Mingus, and apparently everyone else he’s ever met, read, or heard. Wade is the one the narrator has tried to learn from and emulate, although he still lacks the older man’s confidence (not entirely a loss since, alas, that confidence is also Wade’s greatness weakness). Wade acts as a father to the narrator in myriad ways: philosophical, musical, sexual; he also serves as a model for adult life, a proxy for the previous generation in which one imagines oneself. And while the narrator understands Wade’s failings, the younger man still reveres him and fears Wade may simply be more interesting, more fantastic than he could ever be — which is always the fear of the younger generation, that we won’t live up to those who came before us. In this case, though, Wade is pretty fantastic, albeit with the requisite array of accompanying selfish ass behaviors to counterbalance.

And with the idea of the next generation in mind, I want to bring up Enswell, the mythical/renamed town in which the earliest events of the novel take place. It’s not unusual for a novelist to create a fake town, for many reasons. But Enswell works particularly well here: the narrator’s past is so murky, it’s appropriate that it doesn’t even occur in a real place. What’s more, as I was reading, I couldn’t help but be reminded of another Midwestern novelist — a humorist, a smart guy who also likes to sing a song on the radio every week — setting some of his novels in a mythical Minnesota town, not so far from the real world. And this made me want to read Enswell as a tip of the hat, however unlikely, from Hicks to one of his local literary predecessors, and then the whole of Boarded Windows, in some way, as the next generation’s take on a Garrison Keillor Midwestern novel — different in many ways, of course, in all the ways a next generation is different from the previous.

One part of what the current next generation is doing is using the interplay between reality and fiction more aggressively, more comfortable than our older counterparts with the post-meta-fictional, the post-postmodern, using bits of the real world and the fictional world interchangeably. But early in the age of irony, after Warhol but before That 70s Show, most of us in this generation were still unconscious consumers of mass culture: we saw a Burt Reynolds movie, listened to Wings on the car’s AM radio, and ate a chili dog at Dairy Queen (not DQ). All of these artifacts gelled together into an emotional memory of the moment. In a way, what Hicks is doing — what similarly inclined writers, filmmakers and artists of his generation are all doing — is trying to access that collective, lost consumer innocence by referencing those incidental cultural artifacts. He doesn’t just do so by setting his novel’s film-in-progress in 1974, but also by presenting us with a collection of artifacts from a slightly alternate reality.

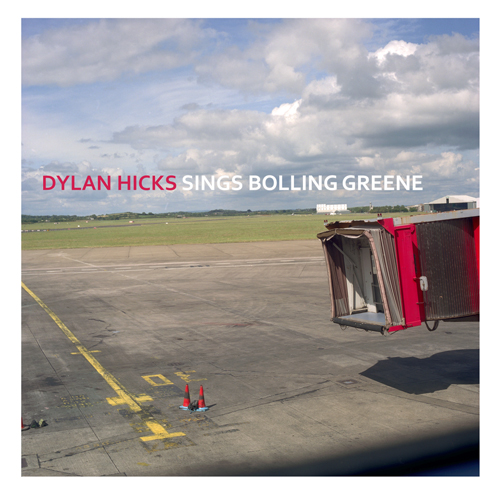

For Hicks, this expanded fictional play means creating a companion LP, called Sings Bolling Greene, adding another layer to the fake past he has created. (The book comes with a digital download, but the LP version of the album is a lovely artifact.) The record is real, and full of great pop songs, but it’s fundamentally a continuation of the world of the novel. The songs on the album are mentioned and discussed in the book (popular music is unavoidably central to the novel, Hicks indulging his love and knowledge of the field); Wade Salem is noted to have briefly played in the band of the aging bad boy country star, Bolling Greene. (Another aside: I have to mention that for us Midwesterners there are few names as evocative as “Bowling Green,” a song by the Everly Brothers, about a city somewhere in the mythical South). The book and the LP, taken together, conspire to create an alternate nostalgic remembrance of a re-imagined past. Perhaps if a novelty candy bar came with the record and book, the set piece would be that much more complete. The only textual giveaway to the real-world truth behind this fiction is that the copyright for the songs is attributed to Dylan Hicks; only in this legal necessity does the game end.

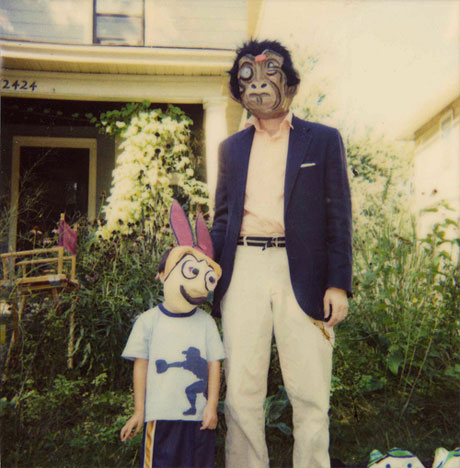

The thing I like best about the book and the LP, though, is something more traditional (perhaps I’m still mired in the previous generation of Burt Reynolds’ movies). On the back of the LP is a photo of Dylan Hicks and his son — or at least a man in a mask standing next to a small boy, also wearing a mask. Even with his face obscured, Hicks is recognizable for the khakis and sport coat; it doesn’t matter if you recognize him though. The photo reads as a father and son. Looking at it, I couldn’t help but think that some day, this boy, somewhere on the way to becoming a grownup himself, would look at this photo, see this guy and say to himself, “That’s my dad, wearing the ape mask next to me when I was a kid” — going through the same, inevitable soul-searching and reflexive storytelling that comprises the action of Boarded Windows. This photo reinforces for me, although it shows something different from Wade and the narrator’s world, what I like most about Hicks’s project — the book and the LP and their fascination with telling and retelling stories, inheritance, how we know who we are. At its heart, the whole thing is a playfully earnest exploration of the relationship between a father and a son, both of whom are reluctant to play their assigned roles, for better and worse.

The conclusion of the book is a well rendered, traditional evocation of longing and loneliness the narrator feels over his missing father. It is a necessary winding up of all things preceding, a refrain of the novel’s emotional tone — and it does so perfectly. That he hits just the right note tying up those loose ends is one more bit of evidence of Hicks’s own skill as a storyteller. He knows how a melancholy song has to end.

______________________________________________________

Related links and events:

Find more information about Dylan Hicks’s new novel, Boarded Windows, on the Coffee House Press website.

The book launch celebration for Dylan Hicks’s new novel, Boarded Windows (Coffeehouse Press), is 7 p.m. Thursday, May 10 at the Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis. Dylan Hicks and the Toughies will play for the CD release party of the accompanying album, Sings Bolling Greene, is Friday, 7 p.m., May 12 at Bryant Lake Bowl in Minneapolis.

After touring around the country, Hicks will return to Minneapolis for a reading at Magers and Quinn June 13 at 8 pm.

For detailed information on future readings by Dylan Hicks in Minnesota and elsewhere: http://www.coffeehousepress.org/2012/01/boarded-windows/

______________________________________________________

About the author: Jay Orff is a writer, musician and filmmaker living in Minneapolis. His fiction has appeared in Reed, Spout, Chain and Harper’s Magazine. Read more on www.jayorff.com.