Resonating/Relating: How Sound Connects Us

From hearing heartbeats in an anechoic chamber to group laughter in Powderhorn Park, auditory perception links us together across bodies, space, and time

I’m fascinated by the sound of my internal organs. As a kid, I’d put my head under the water in the bath to hear the amplified flow of my blood, resonating within and distorted by the walls of the tub.

Last winter, I sat in one of the world’s quietest rooms—an anechoic chamber in South Minneapolis—because I wanted to hear my internal organs. Instead, sitting in complete darkness with a group of strangers, I could hardly discern the sounds of my own body from theirs. As someone working at the interaction of art and science—with much of my research being concerned with how we relate to each other through our sensations and perceptions—this fascinated me. The spatial ambiguity created by the darkness and altered acoustics, made it impossible to differentiate the sounds of their hearts, throats, and even blinking eyes from my own.

The heartbeat is perhaps the first rhythmic constant we hear while in utero. For me, it never ceases to be a reminder of my own or another’s aliveness. Throughout our lives, we continue to gravitate towards similar bodily, rhythmic patterns. Poems written in iambic pentameter, for example, hold a similar cadence to the heartbeat.

Sounds—bodily or otherwise—are a natural tether to ourselves and to each other. While the heartbeat is just one example, sound works to connect us in many ways. We talk. We listen to music together. We make music together. We have points of sonic reference in our environments. We listen to and regulate with each other’s beating hearts. How do we relate to sound and how can it help us relate to and resonate with one another—within our own bodies, across space, and throughout time?

Sound & Bodies

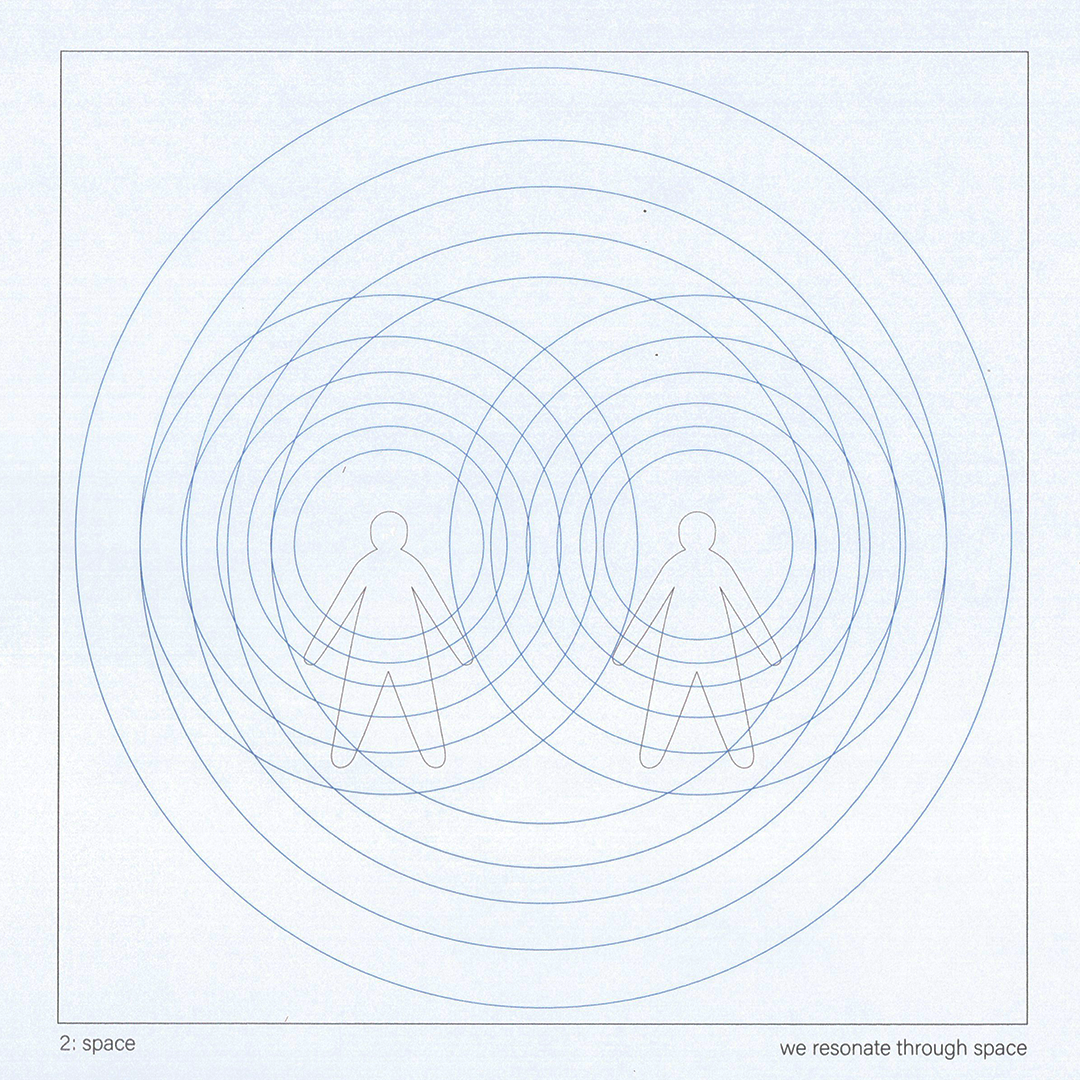

The physical properties of sound, for one, make it akin to reaching out with a hand to hold another. As a fundamentally physical phenomenon, sound starts as quivering molecules of air that affect one another in chain reactions to color our reality. One molecule reacts to the force of a physical event, creating a reaction in which one vibrating particle begets infinitely more vibrating particles. Sound waves are amplified by the outer ear and enter the cochlea. Inside, small hair cells move in response, converting the vibrations to nerve signals that are sent to our brain to make meaning.

Auditory and bodily perception are intimately linked, intersecting and entering the brain via the vestibulocochlear nerve. The vestibular system is contained inside the inner ear and is responsible for our sense of balance, proprioception, and spatial awareness. The vestibular nerve delivers this information to our brains, while the cochlear nerve delivers our sense of hearing. The two nerves meet at the pons—a part of your brainstem that handles unconscious processes—to form the vestibulocochlear nerve, which mediates both our sense of sound and the sense of our bodies in space.

As sound travels through us physically, there are some studies that suggest that we can be neurologically altered by the sounds we listen to. In a series of experiments, researchers asked whether the basic organization of the auditory cortex fundamentally changes when an individual learns that a certain tone is important. Through a learned association, they demonstrated that neurons’ tuning preferences could shift from their original frequencies to that of the learned signal tone.1 Experiences with sound can fundamentally alter the physical makeup of our brains, editing the frequency maps in our auditory cortex.

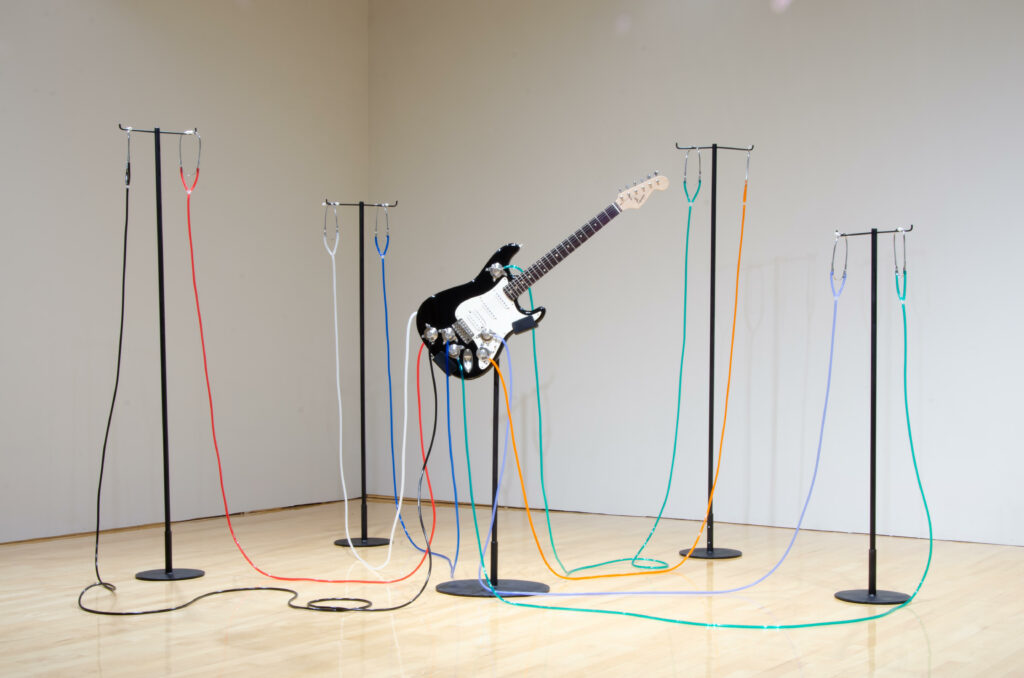

In all these ways, sound is touch from a distance—suggesting that there is a direct, physical process enacted as sound reaches and permeates our bodies. In her piece, Sound and Intimacy, Sophie Eisner explores the directness of sonic touch. In much of her work, Eisner views sound physically, as a sculptural material. By combining stethoscopes with an unamplified electric guitar, she describes her project as an octopus of analogue earbuds. The sound waves are funneled directly to the listeners ears. By manipulating the physical characteristics of this iconic instrument, Eisner changes the immediacy and intimacy with which listeners experience sound. When the sculpture is activated, seven people are invited to listen to a musician play the guitar via the stethoscopes separately and together.

Eisner’s piece also reflects on the act of listening alone versus listening together. Since the stethoscopes are placed at different spots on the guitar, each listener has a slightly different sonic experience. While there is a collective acknowledgement that everyone is listening to the same thing, there is nuance in the fact that everyone heard something different.

Resonating within Space

There can be dissonance between our experiences, but existing within sound together can connect us more physically than we realize. In physics, resonance describes the phenomena that occurs when the frequencies of two vibrating bodies become equal and amplify or prolong the vibration. In psychology, too, there is emotional resonance that describes the idea that our brain chemistry and nervous systems are measurably affected by those closest to us. When we’re together, making noise at similar vibrations—or of similar sentiments—we resonate.

Examples of sonic and emotional resonance become stark, I find, when looking at a smaller spatial or local level. In localized, shared space—like the heartbeats in the anechoic chamber—things resonate more easily and become louder more quickly. Ideas and thoughts resonate too. Across time, we’ve seen groups of people come together to amplify and prolong ideas. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, for example, the sounds of protests and sonic sentiments resonated and were amplified throughout Minneapolis. Many of these resonated so deeply that they were amplified globally.

Yet, as often as sound can be used to create resonance that amplifies the ideas and feelings in a place, it can, of course, be used to amplify and prolong harm. Reflecting on deterrent sound devices that were used by police at protests in response to Eric Garner’s murder, designer and artist Ángel López advocates that, “sound design can no longer be about aesthetics and user ease for the purpose of one institution’s monetary gain. Sound design has to move into a space that scales empathy and a grounding in community-based collaboration.” How, then, do we design spaces that resonate empathy? Spaces where sound helps us relate to one another?

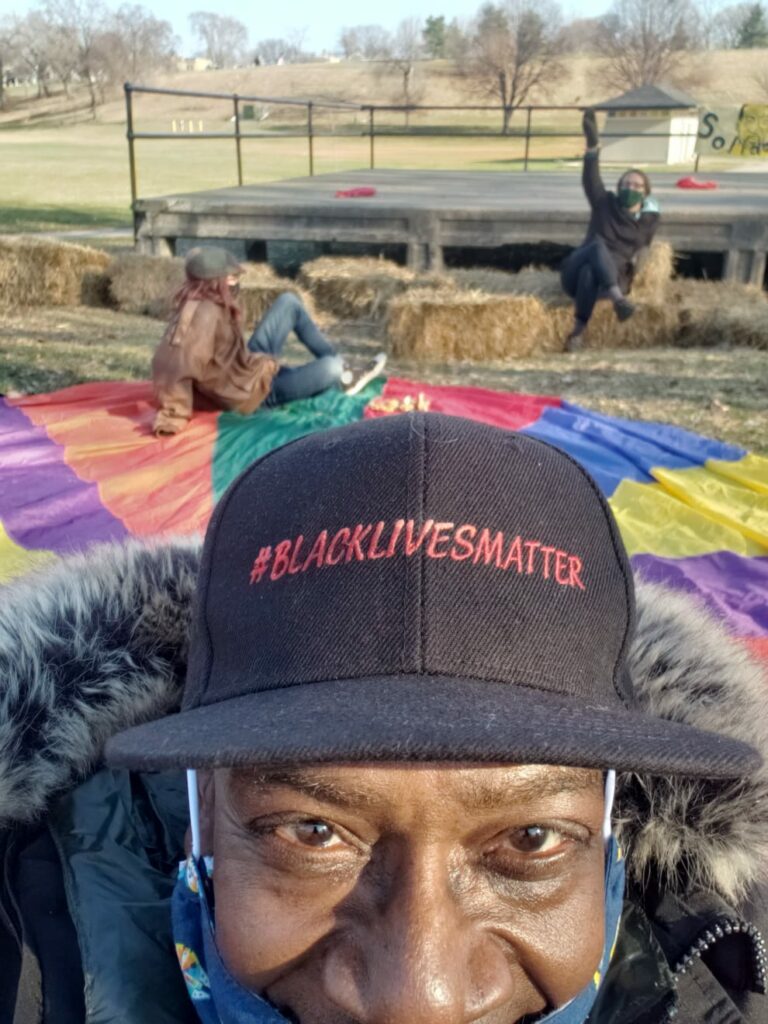

Outside Voices is a location-specific act of emotional and sonic resonance that came as a response to the murder of George Floyd and in the midst of the pandemic. Every week since March 2020, Harry Waters, Jr. has been gathering with a group of people at Powderhorn Park to make sound. These sounds include screaming, laughing, and crying—among others. It proved to be a much-needed physical, sonic release for everyone, where voices could resonate with one another.

Making sounds in groups affects us. Research has demonstrated that making sound together—particularly performing music—increases our pain thresholds.2 In another study, researchers compared the effects of singing together in a small group versus a large one.3 They found that singing together in both group sizes increased participants’ pain thresholds. The larger group, however, experienced bigger changes in social closeness than the small group.

Each week at Outside Voices, people are invited to say something horrible that’s happening to them. These moments range from people dying, to losing a job, to having bad oatmeal for breakfast. Then, once it’s thrown into the circle, everyone laughs at it. “Putting the sound of laughter in the air does something unexpected—even if you’re not intending to laugh, it affects you. There’s a release of tension. The sound does something that resonates with people and we become like kids. It infuses the air with that joy,” Harry described.

These bodily, human sounds of joy and pain are particularly important in relating with one another. Mirror neurons are cells that respond to and mimic the emotions or feelings of other humans to produce a sensation of empathy. For example, mirror neurons facilitate the experience that happens when we see the look of disgust on another person’s face and too feel disgust. Importantly, mirror neurons also respond to sound. That’s one of the reasons why, when we hear laughter, even while we’re in a place of despair, we might too feel joy.4

Relating Across Time

Sound can help us relate across time, to both the past and future. When things resonate, not only are they amplified, but they are also prolonged. I imagine both the screams and laughter in Powderhorn won’t stop soon. When the vibrations are synchronous, they continue, even when the initial source of the sound dies down.

Sound is also a tool to help us reach into the past, perhaps even reminding us of who we are. I recently met a Polish man who pronounced my family name with a verbal acuteness that none of my relatives can since my grandmother passed away this winter. We know too, intuitively and through research, that there is an intertwined relationship between music and memory. A pianist can access the bodily replay of a baroque piece when they perform it, returning to a place in time. Additionally, music is enjoyed by and accessible to many individuals with late-stage dementia.

Beyond music, which is far too vast to fully explore here as a mode of connection between people, verbal storytelling is a powerful means of bringing the past into the present, sending it further into the future. While reading stories is of course an effective method of empathizing with one another, a different type of visceral relation occurs when we listen. The emotional salience that the sound of a voice carries affects us, tapping into our mirror neurons, and we may begin to understand the depth. Research has suggested that when we listen to stories, our brains start to synchronize, going as far as to mirror vocal patterns.5 Additionally, listening to stories helps promote learning through generations.6

History for the Future, produced by LaDonna Redmond, in partnership with Climates of

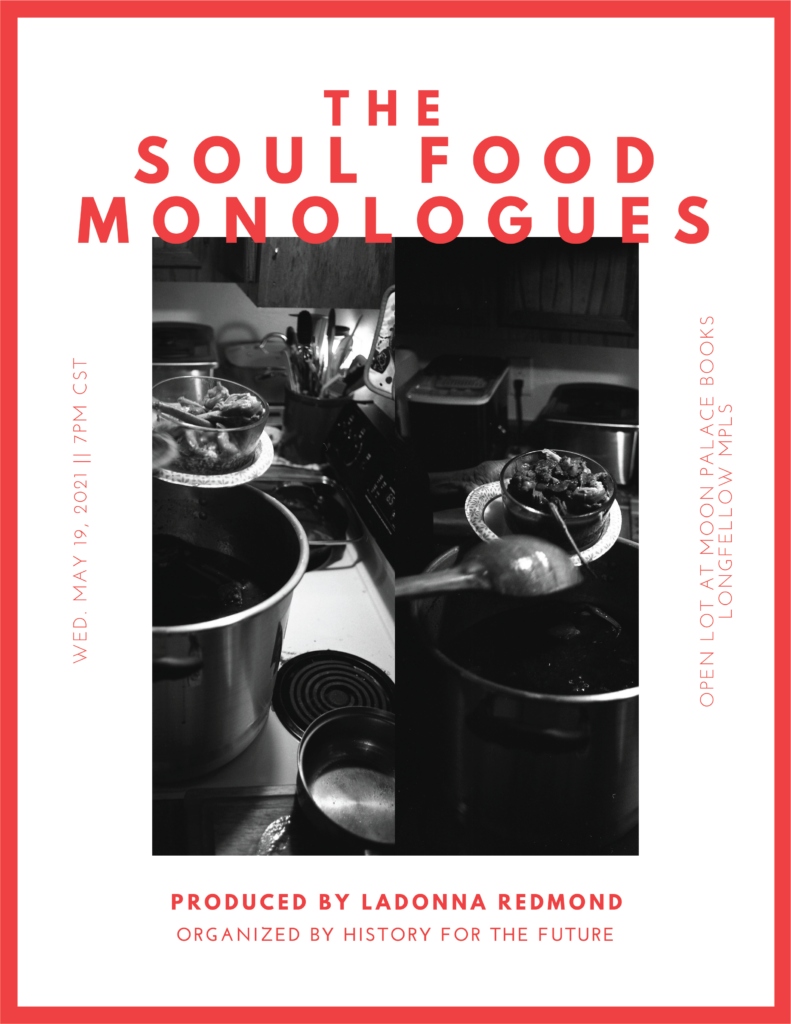

Inequality, a project of the Humanities Action Lab.

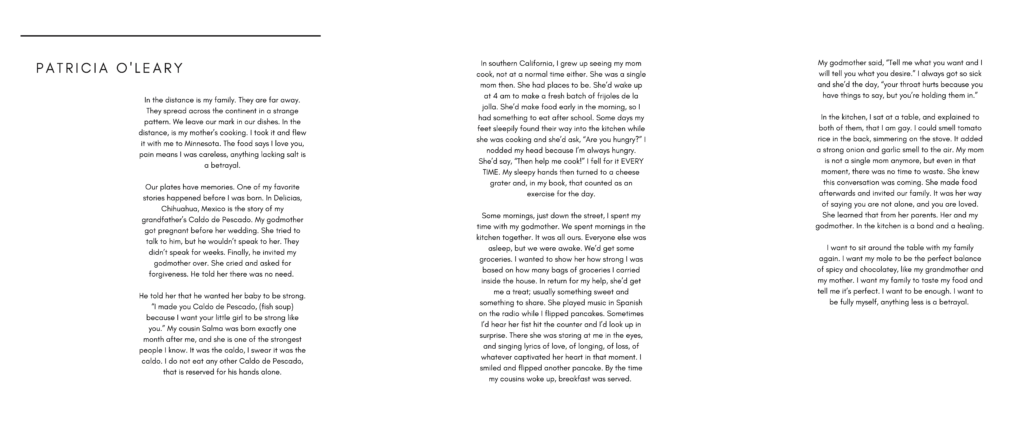

There are numerous examples of storytelling being applied as a connective medium. The Museum of Empathy produced a traveling exhibition, A Mile in My Shoes, where visitors are invited to walk in someone else’s shoes while listening to them tell their story through headphones. More locally, The Soul Food Monologues was a project produced by LaDonna Redmond and organized by History for the Future that gathered five storytellers to verbally tell stories about their relationship to food. The stories documented the relevance of food throughout peoples’ lives, the familial significance it has held across time, and important moments that occur around food. While the stories were ultimately documented in a zine, the verbal accounts were rich with emotion, tears, and laughter.

As Patricia O’Leary, one of the storytellers shared, the experience of telling her story involved reaching back through her memory to bring something once felt into the present. Through her voice and words, she offered the audience points of empathy, where they too could feel the strained speech and tension of her story.

“When building my story, my body felt curious and focused on remembering what my senses were picking up in my memory, which was the smell of my mom’s Mexican rice. My story involved food, family, and coming out as queer. At an early age, I thought my queerness was something I would take to my grave. Nobody in college knew I was gay, not even the people closest to me. A few years later, there I was having a conversation with my mom and my godmother at the dining table about it. During the Soul Food Monologue, I stood up and admitted my queerness into a microphone. I felt short of breath, I felt tight in my chest, and I felt warmth in my eyes. I did something my past self never thought I would, and everyone sitting in front of me contributed to that moment with their presence,” she shared.

Concluding Thoughts

Deniz Peters, a professor and researcher interested in musical empathy, writes, “music is a compound entity: born out of a confrontation with the often unnamed and ineffable traces of others in us—of life as it affects us, of individual encounters and encounters with society, culture, and nature. Musical empathy is empathy with a protean agency, an agency whose sometimes mundane and sometimes bizarre body and psyche emerges, profoundly co-constituted, from ours.”7

While Peters’ research focuses on music specifically, I think sound could be seen as the building blocks for this larger confrontation with the other. From what begins as small vibrations that affect our bodies on a cellular level, we build worlds. We perceive discernible, bodily, and emotional sounds—laughs, cries, and screams—that allow us to understand each other on a basic level. These sounds turn into phonemes—the smallest unit of sound in a specified language. These serve as the building blocks to create the stories we tell each other about our pasts, allow us to engage in the present, and imagine new futures that can be amplified across space and time.