Carrier Bag of Recovery

Thinking with the influential essay by Ursula K. Le Guin: on the shape of recovery narratives, stories without origin or endpoint, the things we carry and the things we share with each other

Days before I checked into rehab, my friend Ben told me that I’d probably have fun there.

He said: “You’ll, like, sit in a room and get talked at, but then you get to go outside and smoke a bunch of cigarettes with other addicts and one person will be like FUCK THAT BITCH! And then you’ll all be like FUCK THAT BITCH!”

I was excited to chain smoke. I was excited to yell FUCK THAT BITCH with a group of other people who, in some way, understood a part of me that I didn’t allow myself to otherwise see. A part of me that flickered in my periphery for so long, until, finally, it snaked out into a full view as a deep fissure in my foundation.

My sister dropped me off, and we hugged for three long minutes in the doorway of gay rehab until the admin person clicked her tongue like that’s enough. I was left achy-eyed with my moss green body pillow and my favorite Samuel Delany book in the care of a butchy tech with a clipboard. They confiscated my phone and could tell that I’d already been drinking that morning. I knew that they knew because of the gentleness in their voice when they addressed me. Shame, my oldest skin, puckered hot, no it burned, but I couldn’t numb it away this time and, beyond that, this time, this time, this time, at least, I believed it signaled the end of something. I was done.

But you, dear reader, are savvy with narrative, no? You know, of course, that it was just the beginning.

What kinds of stories do you like? If we were walking together, this is the kind of question I would ask you while we ate soft-serve or looked up at trees and talked about the shapes that came to life in between their branches. You are my sibling, you are an artist, you are someone I am hoping to get to know. You might say that between the slingshot curve of cottonwood and a faraway cloud’s vanishing question mark, you could see the profile of someone you remember loving in a different lifetime. You are my best friend since I was 19, you are my roommate in rehab. You work at the corner store by my house. You are my brother. You could tell me a story about the first time you went out of town with this person or the last time you celebrated the holidays with them and, depending on the day or how you feel or our relationship, we would constellate a certain and contingent kind of shape.

These are the stories that I like best: the kind dependent on time and place, the kinds of stories that have an intrinsic and delicate relationship with the world around them. The kinds of stories that wander, and give off spores, and teem wildly, without origin or endpoint.

In 1986, Ursula K. Le Guin wrote one of her most influential essays, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.” In it, she’s committed to a way of telling stories that is more true to the ways that people actually live, and survive, together: through gathering. Le Guin is fully in her signature straightforward, playful mode, valorizing above the spear and the hunter, “A leaf a gourd a shell a net a bag a sling a sack a bottle a pot a box a container. A holder. A recipient.”

The essay is mesmerizing, I think, for its simplicity without simplification. This ability of Le Guin’s—to distill without diminishing—I take as not only the skillfulness of an exemplary thinker, but as a gesture of extraordinary kindness. For example, a prescriptive (albeit weaponized) reading of this essay might locate Le Guin’s feminism in a kind of gross characterization of spear-as-phallus-as-in-bad and bag-as-womb-as-in-good. But she refuses to pose these entities and types of stories as against one another, necessarily; rather, they contain each other, and are unfixed. Stories, for Le Guin, are in motion:

“Conflict, competition, stress, struggle, etc., within the narrative conceived as carrier bag/belly/box/house/medicine bundle, may be seen as necessary elements of a whole which itself cannot be characterized either as conflict or as harmony, since its purpose is neither resolution nor status but continuing process.”

What she opposes is linearity, resolution as goal and thesis and truth, the egoic conviction of a story’s finality. She calls this the killer story. In my mind’s eye I see a road bridge lit up in red and time as a brute, and delicate, unbusy forms of life greying into husks. I see going going going, and somewhere that I need to be, far away from here.

In 12-step programs, there’s a lot of emphasis placed on an addict sharing their story. A story is something that you share to help others. A story is something you share to make sense of where you are now. A story expresses gratitude or regret or every other shade of human feeling, and most of all, a story doesn’t leave this room. It is shaped by the people, place, and time of being together. A story is about being together.

I learned quickly in treatment how to tell my story towards satisfying ends. I fixated on the end, and still do: the painful riddle of addiction in my family’s lineage, finished with me. The long days and nights of ache, the wounds I picked at because I was bored or powerless, the sting and the bruising and the death now washed anew in hope. The future: a blazing light that I was now ready and primed for. That I was now appropriate for. I had arrived. I had become. I had done it. I was done.

Imagine how I felt then, my friend, as the adult child of alcoholics, the spear-wielder who had finally put the ghosts of my lineage to rest, encountering this moment in Le Guin’s carrier bag:

“I now propose the bottle as hero.

Not just the bottle of gin or wine, but bottle in its older sense of container, in general, a thing that holds something else.”

In a version of this essay, I start here, with a point:

Recovery is a way of writing, and I know this because recovery and writing are both ways of being with the world.

But this way of prompting this essay is stultifying. It demands that I prove and show, that I domesticate the wildness of both story and recovery into an answer.

I work with a therapist who tells me that he doesn’t find relapse to be a useful concept. He asks me, at least, what I think about it. I am stopped. I didn’t know I had the choice to conceive of it. I mean, to an addict, isn’t relapse matter-of-fact, fully formed, a thing with gravity and direction?

The bottle, after all, is something that I take from, not something that I look back into. It is something that pours, and damns all it pours towards. I’m not interested in what the bottle could possibly hold, or if, in another life, it could be a vase of dried flowers or vessel for found marbles or an instrument that reverberates with breath or touch.

There was a small marsh behind the rehab facility where I read, and watched deer, and, yes, chain-smoked and yelled FUCK THAT BITCH! with a chorus of other addicts. Most often, I sat, and stared and cried openly, swatting mosquitoes. Soon, fireflies glowed above the grasses, the marsh’s summertime eyes. I talked to myself a lot, and I put a lot of pressure on myself. I was going to be somebody after this experience. It all had to mean something to be anything.

Le Guin’s tenderness in “The Carrier Bag of Fiction” strikes me most when she talks about what makes us humans so human. Rather than “the Story of the Ascent of Man the Hero,” we have the very human compulsion to store something because it is “useful, edible, or beautiful.” I am moved that she names the bag and the basket and the rolled bark or leaf and the net woven of your own hair. They are all important, and distinct, our carriers and what we carry in them. They all deserve to be named, and their stories unwound for their own shapely livingness.

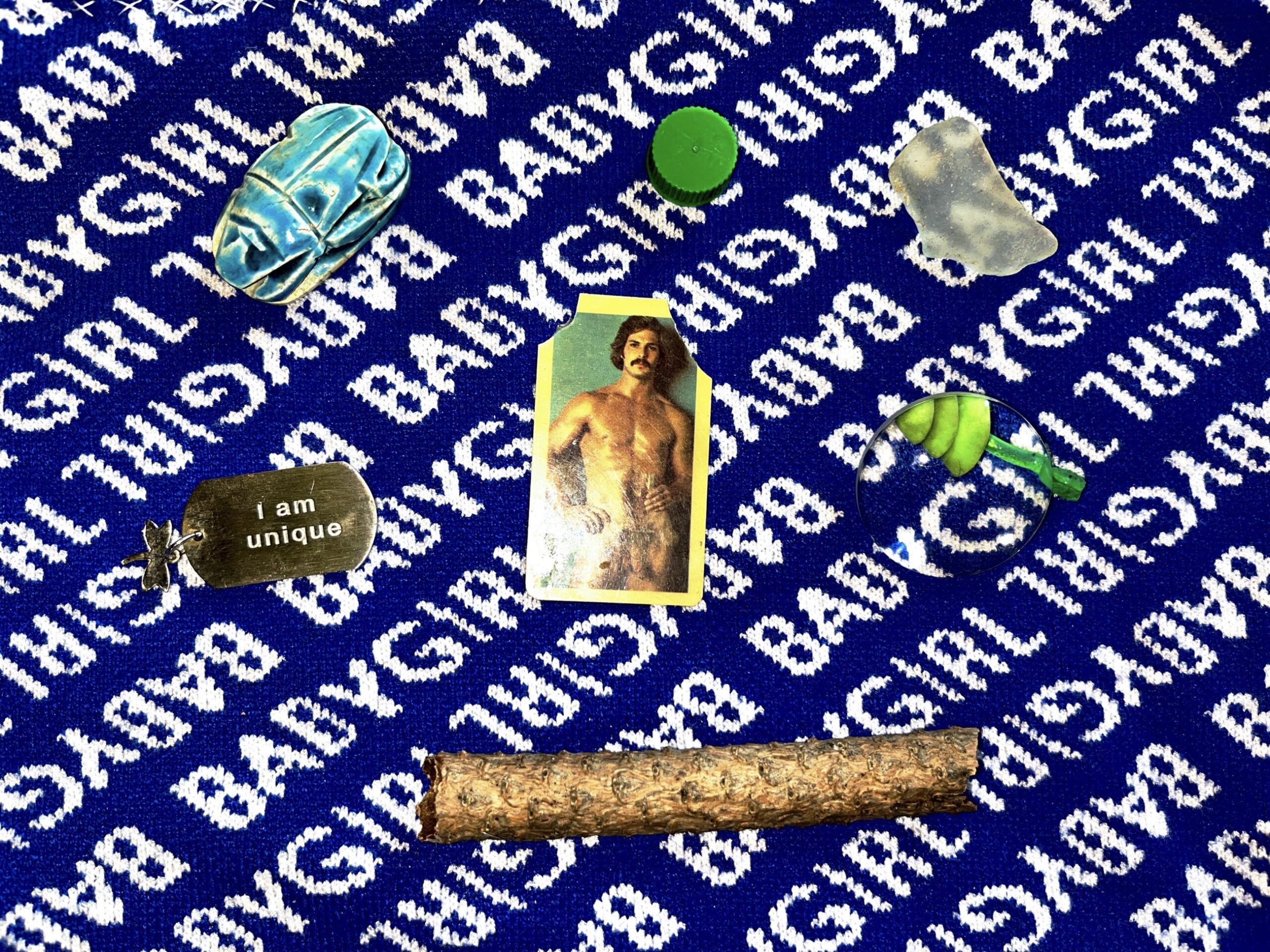

Because when I struggled so much after graduating rehab and being done, you wrote me a postcard, and I put it on my wall. Next to the small piece of hematite your lover gave me. And that lock of my hair when I shaved my whole head? I gave it to you in an Altoids tin. And you copied for me a poem by Paul Tran in your hand that I read every time I am feeling haunted. And I keep that wooden bowl on my altar, and I fill it with black walnuts. And, no, I haven’t opened that box of matches because I find them too beautiful to use. And this is a copper bowl of water. And this is a stack of cards that you’ve mailed me every year since my father died. And this is a box of incense I bought in California, when I met you for the first time and it felt like we already knew one another. And what we shared in those years, I keep upstairs, because I’m too afraid to look at it, but I’m still holding it, and one day I will be ready.

And when my hands hold a pen, I feel a phantom fear, like I’m supposed to get somewhere or otherwise I’ll risk being forgotten.

Lately, I think my favorite stories are not unlike my walks with you. You tell me what you listened to on the radio that day in your car, and I tell you what I’ve been reading, but mostly we list things. We trade names for plants that we see and know. We point to red sliders making their way into the pond.

My recovery is really a form of noticing, a way of being together. My recovery has made my life, and my writing, more complex but less complicated. In order to look inside, I must really commit to looking, and what I notice can be described but not easily calcified into a state. It’s all process: the package of bacon I got free from work that you picked up on my porch, the book that I earmarked for you, the tins of mackerel that we each chose for each other the night that I got so drunk I howled. What holds this process together, for me, are the infinite you’s that I have the opportunity to connect with in my life. The shape of my story is contingent on you, and you, and you.

And in this process, this recovery, the pen too becomes less of a tool and more of a way. It carries me, if I can allow it to. If I can trust enough that this gentle acknowledgement of the way we are always held and holding, too, is enough. There is nowhere to get to, in writing or in recovery. There’s only the blue marble rolling in the bottom of my bag, waiting to be passed between my palm to yours.