Objectifying Time

Photographer Peter Happel Christian is as concerned with the material experience of his medium as he is its results: that fleeting moment of attention caught by his lens, the tangible effect of time's passage on image, print and paper.

PETER HAPPEL CHRISTIAN’S EXHIBITION,Sword of the Sun, at Macalester College addresses the materiality of photography literally — his work is as likely to materialize as object as it is in print. Framed contact sheets, a photogram, a few color prints, and a sheet of photographic paper developed with the drag of dripping chemicals, all hang in the gallery among a series of sculptures made from cardboard boxes, mirrors, shards of glass and two tables of meticulously ordered sundry materials. The tables are laid out in such a way that the various articles serve as detailed citations, evidence of mental associations connecting shape and form, documentation of the material resonance between objects, time, nature, and the photographic record itself.

The contact sheet is a longstanding resource for photographers. Displaying positive images of the photographs on a roll of film, contact sheets are primarily used to make selections of one photo over another. Happel Christian presents them for view as a whole, both hanging in frames and laid out on the tables. Capitalizing on the shifts from one frame to another — depicting the same subject from different moments and perspectives — he treats the contact sheet’s assembled thumbnails as a meditation on the movement of his attention through the flux of the world. Some of the contact sheets are pulled from work made years earlier, so that the photographic record’s preservation of time looks both forward and backward. He’s effectively exhuming past intuitions and repurposing them in his aesthetic and conceptual present.

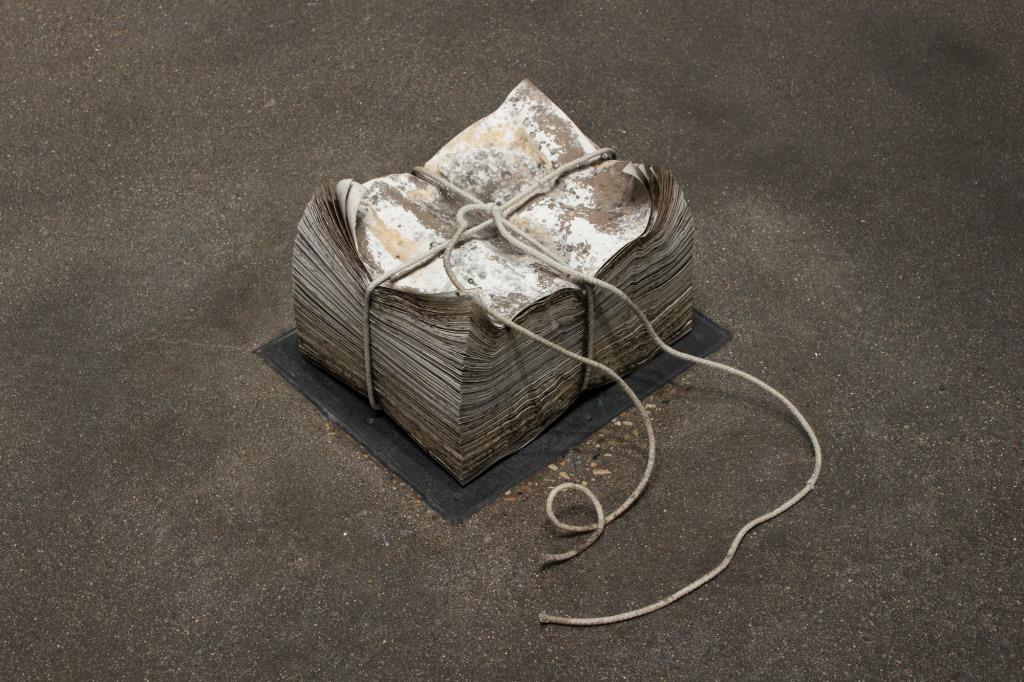

In Once Around, two bundles of paper rest on the gallery floor. Happel Christian tied up and placed a stack of 365 sheets of 8.5×11” black-and-white fiber paper next to a stack of 365 sheets of 4×6” resin-coated paper; he then left the bundles of paper on a cedar pallet in his yard for one year. A year’s worth of sunlight exposed the paper but no images, while the warp of the weather wrote itself onto the surface, developing a record of the sheets’ time in the sun, wind, rain, and snow. The pallet is displayed in the exhibition, propped against the gallery wall as if casually moved out of the way and forgotten, its purpose complete. Some mixture of soil, moisture, pulp and emulsion have marked the pallet’s surface where the bundles sat. Their removal appears to have been forced: a chunk of raw wood is now visible at the corner of the larger stain, as if it had to be pried loose. Small patches of paper remain where the bundled sheets resisted separation from their resting place. It is as if the paper, under the weight of a year’s exposure to the elements and in recognition of material kinship with the wood, began to bond to the pallet.

____________________________________________________

By way of these images and assemblages, Happel Christian exhumes past intuitions, repurposing them in his aesthetic and conceptual present.

____________________________________________________

Three straightforward color prints, Search/Shade I-III, hang on the wall, but unanchored at the base so that the bottom edge rises, ever so slightly, out into the space of the gallery. The figures in these photos cover their eyes to block the intensity of the sun above. Their arms create a diagonal that reappears in other images and objects throughout the gallery space. Indeed, such forms recur throughout the exhibition — circles, crescent moons, narrow rectangles, etc. The figures are determined to look at the sun — our most basic marker of time’s passage — despite their inability to do so without mitigating its brightness. Their determination is indicative of the way Happel Christian asks us to look at the materials in the exhibition. He presents items for view, shaped by the power of time and light, while exposing for us the mediating process of his physical shaping of objects and images in order to bring us to these perceptions.

Against this backdrop, the aforementioned tables, Infinite Field II & III, become a kind of research hub for all of the other pieces in the gallery. As a collection of data the assemblages are at once tantalizing and elusive. Stacks of cut-open security envelopes are layered one upon another next to neat piles of photographic images that beg to be lifted for a quick look beneath. Happel Christian simultaneously splays open what is hidden while obstructing thorough inquisition. Taken together, his stacks of photos, papers, and open book pages create new compositions; their discrepancies in size and degree of overlap allow for one to extend out from under the other. We may wish to see that which is still unavailable, but the interplay of images we are given offer propositions at least as compelling as the mystery of what might yet lie beneath.

Objects of obvious significance — black mirrored stones, finely printed photographs, a collection of clay discs with impressions formed by sea-glass — are juxtaposed with what appears to be the material detritus of Happel Christian’s studio process: wedges of wood, slivers of paper from trimming prints, halves of photo paper boxes, a disposable camera still in its silver wrapper. The equivalencies generated by these relationships allow the byproducts of creation to reclaim a place of importance in the construction of thought and experience. Small rocks serve to weight books and prints down onto the table; other stones serve to support the glass tabletop and the angled feet of the sawhorse legs. The archeological precision of the distribution of objects over the table orders these artifacts of material experience and interaction, all with equal deliberation and intention.

In Sword of the Sun, Happel Christian forms a coded but only partially decipherable legend for the interconnectedness of light, time, and our ability to process the experiences of each. Put together on a sturdy conceptual structure, the impact of this work is first viscerally material as a phenomenal experience.

____________________________________________________

Related exhibition details:

Sword of the Sun: Peter Happel Christian is on view in the Law Warschaw Gallery at Macalester College, St. Paul, from February 7 through March 14, 2014. For more information, including gallery hours: www.macalester.edu/gallery.

____________________________________________________

About the author: Lex Thompson‘s photographic work focuses on manifestations of hope and failure in the American landscape. With a BA in history from New College of Florida, an MA in Religion and the Visual Arts from Yale University, he continued his studies at the San Francisco Art Institute, where he received a Masters of Fine Arts in Photography. He is Professor of Art (Photography) at Bethel University in St. Paul, MN. He is recipient of a 2010 McKnight Artist Fellowship for Photographers, a 2008 & 2011 Minnesota State Arts Board Artist Initiative Grant. His artwork is included in collections at the Getty Research Institute, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Stanford University, University of California Los Angeles, and Yale University, among others.