Midwestern Masculinity: Decoy and Drag

On regional constructions of gender, shifting relations to survival, mancrafts, and object drag

In August 2023 one of my best friends1 and I set out to drive my possibly-dangerously-rusted ‘01 Ford Ranger from Minneapolis, MN to Seattle, WA in a 1,662 mile road trip, stopping each night to tent camp. The route begins in Minnesota, continues through North Dakota, then Montana, and cuts through the smallest slice of Idaho, before finally ending in Washington. Of these five states, three of them—North Dakota, Montana, and Idaho—are considered states with the “Worst Active Anti-Trans Laws.”2 They are nestled between Washington and Minnesota, states considered some of the “Safest States with Protection.”3 Many of the anti-trans laws that exist or are being proposed in the Worst Active Anti-Trans Laws States are so-called bathroom bans, legislation that attempts to force people to use bathrooms consistent with sex assigned at birth. Before embarking on the four-day long journey, I remember telling a new friend4 about my upcoming road trip plans, and her immediate concern regarding my transness and the hostile climate of some of the states I planned to drive through.

I love the Midwest. I was born here, and, until recently, had only lived in Midwestern states.5 However, the rise in anti-trans legislation, coupled with a job offering, led to my recent move from the Midwest to the Pacific Northwest. In the months leading up to this move and the road trip, I began to think about gender in relation to regionality, and how the Midwest has shaped my own perceptions of gender. How can these perceptions be inverted, changed, or played with? How do I fit within, outside of, or alongside them?

I also began to think about how these regional gendered perceptions worked in the world of craft. What kinds of crafts are regional, and how does gender play a part in that narrative?

“Jean thinks the increasing number of sportswomen will most enjoy fly fishing, which represents the supreme challenge of trying to fool a wily trout with a few feathers tied to a hook. ‘Fishing no longer takes masculine strength,’ she says.”

Saga Magazine, Vol. 51 No. 1, October 1975

In the Midwest, getting drinks with friends at a bar I don’t remember the name of, a white woman flinches and rushes out of my way when I walk out of the women’s restroom.6 Later, I see her glancing at me, and muttering to her husband. She seems to be upset.

The 2020 lockdowns due to COVID-19 led to a rise in outdoor recreation, with many national parks seeing record numbers of visitors. Recreational fishing benefited from this rise in outdoor rec, which still continues in 2023. The Midwest in particular felt this boom, with six Midwestern states belonging on the “Top 10 States to Fish.” Growing up in Missouri, I was introduced to fishing at a young age, and when I think back on a lifetime of witnessing Midwestern masculinity, hunting and fishing both feel like obvious attributes of the stereotypical Midwestern Man. Taking particular interest in fishing, hunting, woodworking, carpentry, and the mancave7 in relation to craft, I began using the term “mancraft” to describe these regional masculine activities and the spaces they occupy.

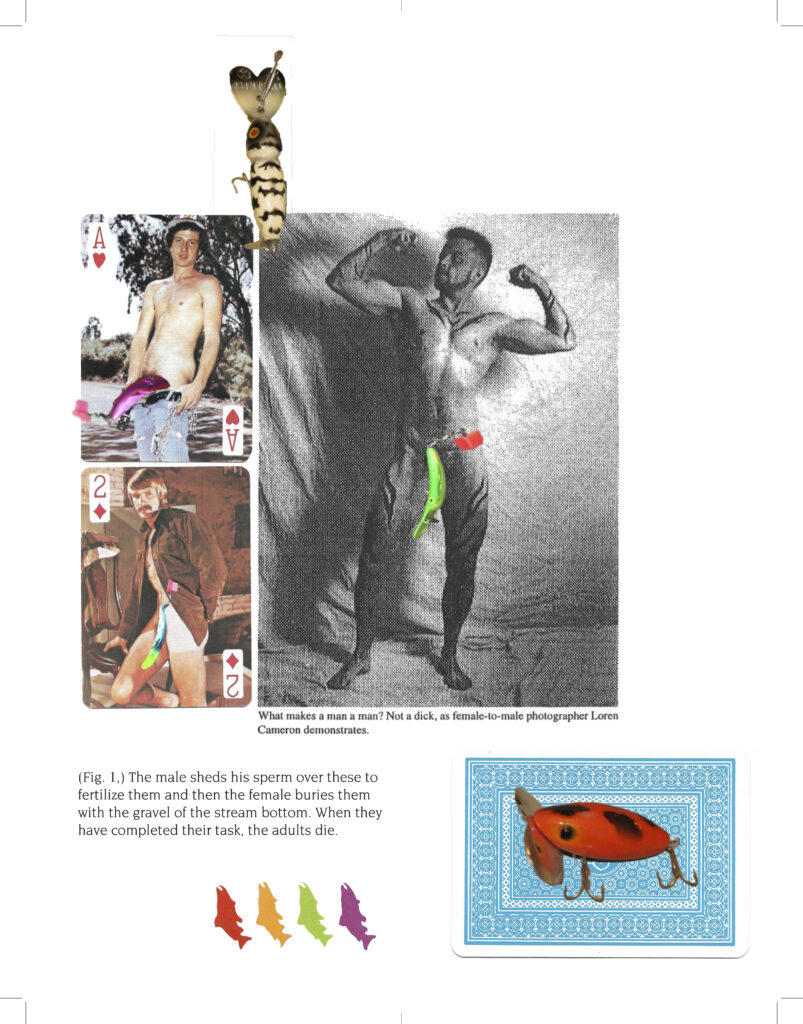

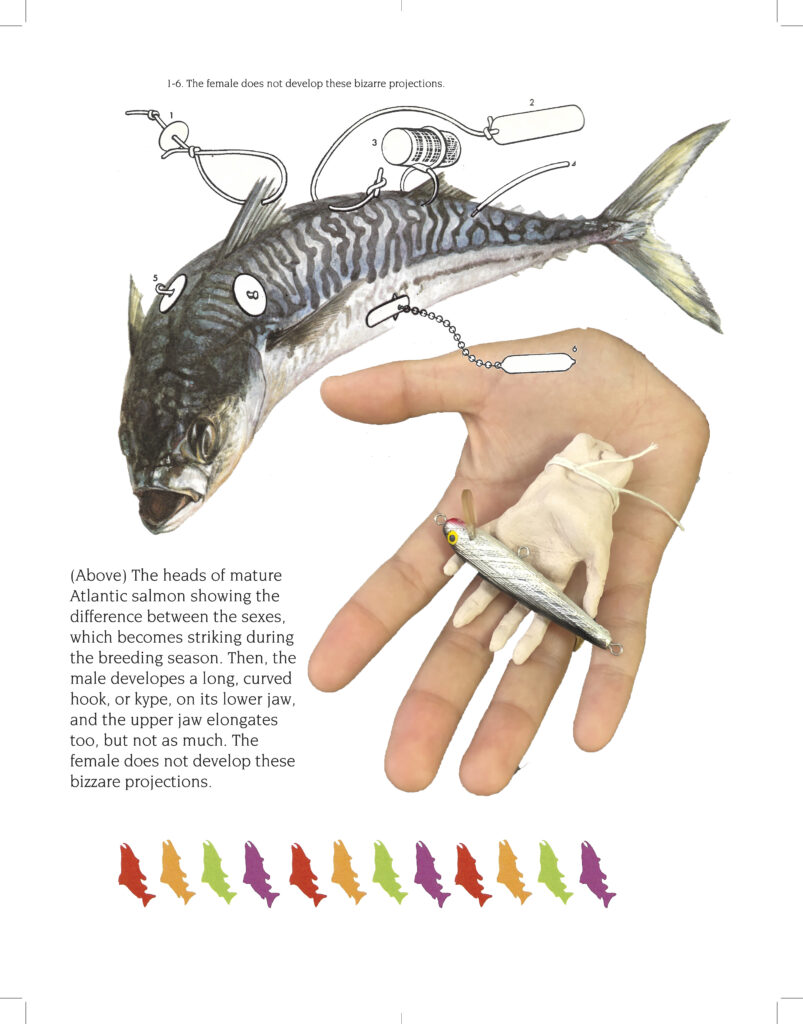

Fishing lures and flies are gorgeous objects. Imitations of real aquatic insects or prey animals, they are made using both natural and artificial materials. When removed from their functional setting, they have a certain flamboyance to them, often neon or sparkling. Seeing fishing lures and flies together reminds me of watching a drag queen;8 they are performative and enticing. The juxtaposition between the butchness of fishing and the pure flamboyance of the lure or fly feels akin to the gender fuckery of a drag performance. The scraps of glitter and neon, flashy chrome (almost like an earring), and bits of fur and feathers all come together to create a cohesive illusion or performance.

“[…]a good decoy is one which under a given set of circumstances best serves the gunner.”

Duck Decoys and How to Rig Them

Like fishing lures and flies, duck decoys (or decoy ducks) are imitations of real waterfowl. These decoys can be made from real or artificial materials and are used to attract birds for hunting. They are functional tools, as well as respected folk art objects. Duck decoys range from ultra-realistic, to anything that can float in a vaguely duck-like shape. Unlike lures and flies, duck decoys function not as an imitation of food, but as a façade of safety. A duck decoy fools a duck or flocks of ducks into thinking that a body of water is safe from predators and full of resources.

In the town of George, two hours east of the Washington-Idaho state line and two hours west of Seattle, my road trip buddy and I make our last stop before we arrive at our Seattle destination. He runs inside to use the bathroom and I stretch and debate whether or not to go inside for a snack as an excuse to get cash back to pay for gas.9

When he gets back he greets me with a, “Dude, it is weird in there.”

Looking around the gas station at the mix of truckers, actual cowboys, construction workers, and road-tripping families, I wonder what he means.

When I make my way inside, and I am greeted by the sight of white men wearing shirts that show various iterations of the American flag with handguns strapped to their belts, I feel like I understand what he meant. I duck in and out of the bathrooms as fast as possible10 and decide to eat the extra 10 cents and just use my credit card to pay for gas.

How does drag function differently than decoy, than imitation? Is a performance of gender like a decoy?11

The conclusion I have come to for now is that decoy indicates an element of survival. It is a trick used to gain something, like a duck or fish for dinner. Gaining something through trickery feels very survival-oriented and that seems like a very important distinction to make between drag and decoy.

During my research and studio work, I created the term “object drag” to refer to the performative nature of both real-life mancraft objects, but also the sculptural paper maché duplicates I make of them. By creating paper maché sculptures that are duplicates of real-life objects performing a false functionality (for example, a paper maché hatchet cannot split wood, a paper maché decoy duck melts in water) I am able to parallel an experience of a performance of gender. I do not refer to this work as “decoy objects,” but as “object drag.” I do not want them to be oriented within a mindset of survival, because I am tired of orienting my own mindset and my own performance of gender towards survival.12 Instead, they are drag objects, objects of playfulness and performance, camp and community.

When we stop on our road trip to get gas in Idaho, the cashier inside hands me the keys to the men’s room without a second glance.