Crafting Queer Futures: A Conversation with Embodied Material Artists

A reading group creates an exhibition at Fresh Eye Gallery at the intersection of queerness, textile making, and community

A conversation with Embodied Material reading group and exhibition facilitator Soph Munic (they/them) and participating artists Drew Maude-Griffin (they/them), Raye Cordes (she/they), and Riley Kleve (they/them) about the relationship between queerness, textile making, and community. Embodied Material is at Fresh Eye Gallery until July 29, 2023.

OLIVIA COMSTOCKSoph, you served as the reading group and exhibition facilitator. Where did the idea for the reading group originate?

Soph MunicI attended a two-week workshop, “Queer Textile Strategies,” at Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts in Tennessee last summer where we explored felting, weaving, and quilting while reading queer and textile theory. It was the first time I read theory out loud with a group of people. The experience gave me new language for the relationship between my work and identity. I wanted to keep that going by facilitating spaces in Minneapolis where artists could explore theory together.

OCOne of your goals was to have a communal space to think with others outside of an academic classroom. Why was that important to you?

SMI hear from other artists how challenging it is to find an artistic community outside of academic spaces. In Trans Girl Suicide Museum by Hannah Baer, she says that so often in academic spaces, to have an opinion about theory, she has to say why the text is wrong, but she is more interested in discussing how a reading makes her feel. I try to bring that sentiment to the group. I want us to take what we need and want from a reading rather than needing to appear “intelligent.”

OCPart of what interested me about your project is that you translated the community reading group into an exhibition. How did the project evolve over the course of the meetings?

SMThe communal conversations from the reading group acted as a layer of the curatorial process. The first reading we did together as a group was the chapter “Queerness as a Horizon” by José Esteban Muñoz from his book Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. At first, the group didn’t really know how to feel about Muñoz’s idea of queerness as a horizon. They said, “I’m queer now.” However, every conversation we had afterwards always circled back to this text. I didn’t expect people to have such an arc of emotion with a reading over time. That felt sweet!

OCIn the description of the exhibition, Soph wrote that the show materializes the inherent queerness of textiles. How are textiles inherently queer, or what makes an object queer to you?

Raye cordesI use materials in unconventional ways. That makes textiles feel queer, but also the fact that I am a queer artist making my work makes it queer. My piece Open in the show is made using rug tufting. When people think of rugs, they think of something on the ground, walked over, and used. However, Open goes against these expectations because it is a soft three-dimensional object on the wall.

OCDo textile practices seem to have a closer relationship to queerness than other forms of art?

SMFor me, the inherently queer nature of textiles comes from their proximity to the body. Artist Ann Hamilton said that textiles are the first house of the body. In everything we do, there is some type of fiber to keep us warm, hold us, protect us, or identify us. When I try to describe how queerness and textiles relate to one another, it almost feels redundant. Breaking it down to describe the two can feel like I am unweaving or untangling something.

RILEY KLEVEIt is hard to create textiles in isolation because the techniques are traditionally used in community. If you’re quilting for an artwork, the point of reference is still quilting practices in general, which are always done with other people. Similarly, queerness doesn’t exist without people in connection to one another.

OCI love thinking about that connection between relationality and craft. The reading group was also a relational, communal experience. How did it feel reading and thinking with queer artists versus other times you’ve engaged with dense texts? How was this different from reading on your own?

RCIn the meetings, anyone could say they didn’t understand something. Then we talked about why we didn’t understand and what we did get. It was a space to be vulnerable. When I am reading on my own, it is easy to feel like the material is too hard, I should just put it aside, and not open it again. However, with this group, I was challenged to continue talking about the reading, even if I didn’t fully understand something. Someone else always felt differently and could help.

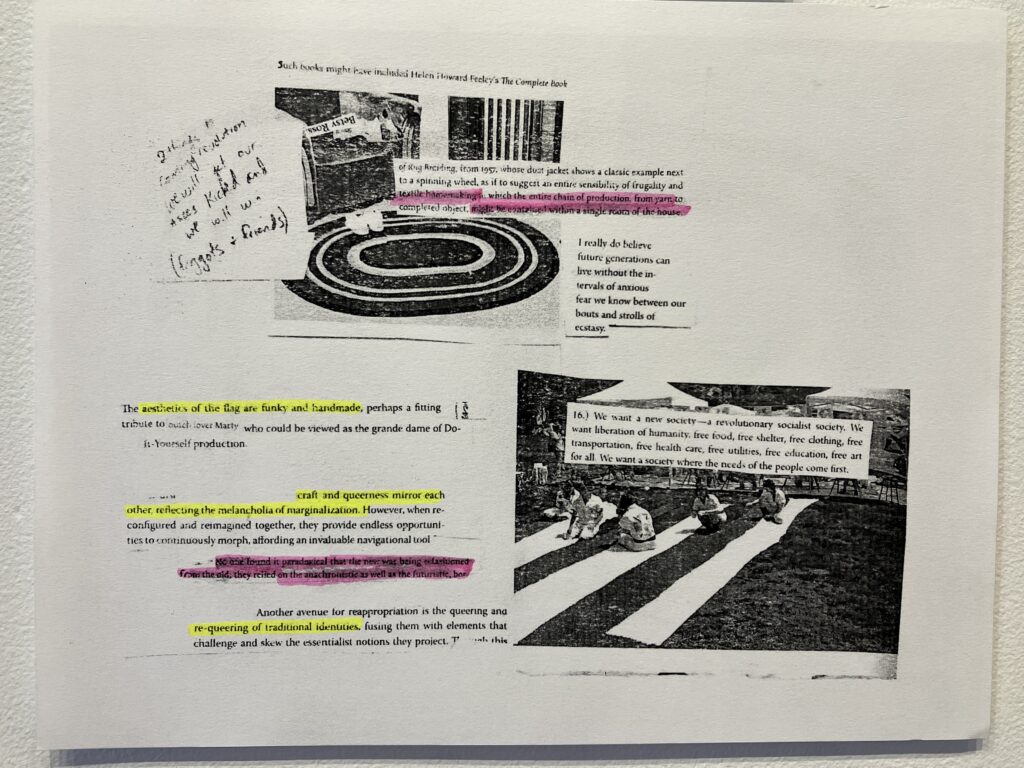

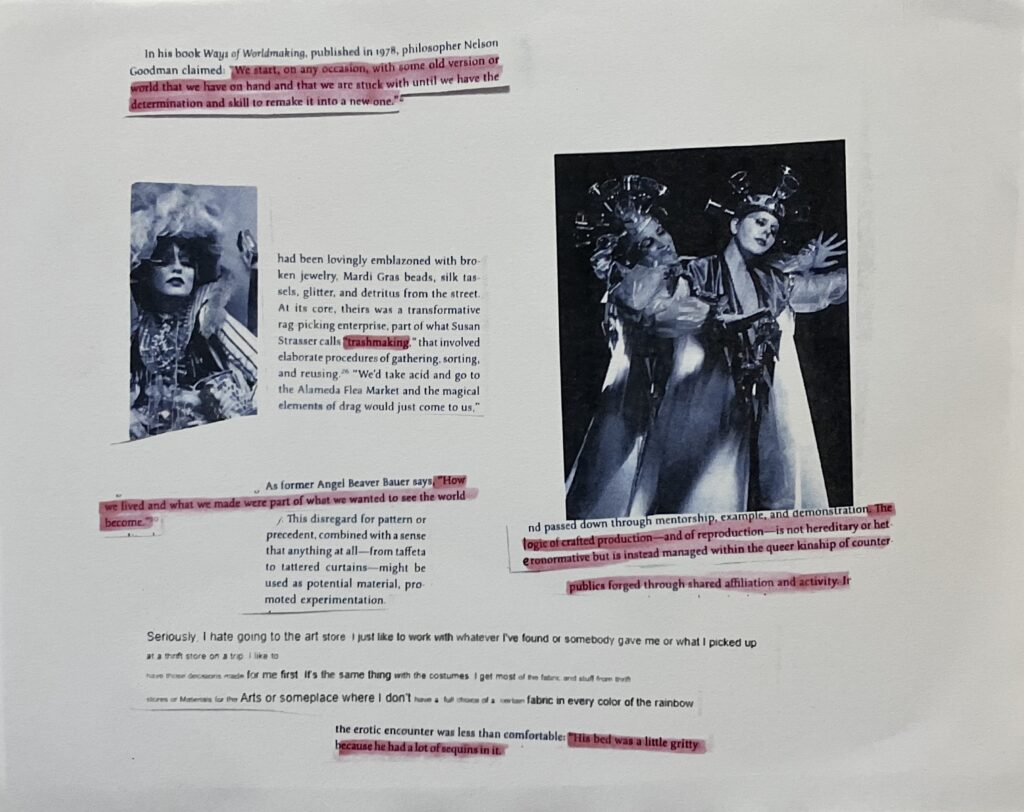

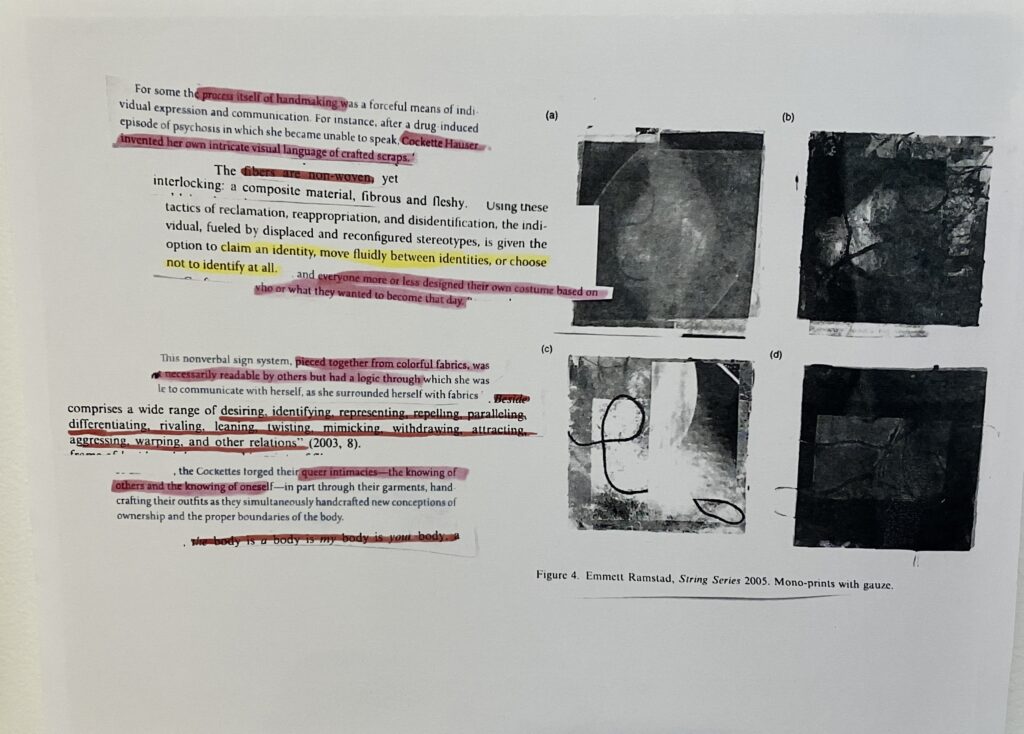

Riley Kleve’s annotations of Julia Bryan-Wilson’s text. Photo: Olivia Comstock.

Riley Kleve’s annotations of Julia Bryan-Wilson’s text. Photo: Olivia Comstock.

Riley Kleve’s annotations of Julia Bryan-Wilson’s text. Photo: Olivia Comstock.

OCAs you were preparing your pieces for the exhibit, were there any specific readings you had in mind that you were responding to?

RKThe chapter “Queer Handmaking” from Fray: Art and Textile Politics by Julia Bryan-Wilson stuck with me. Her descriptions are so vivid and connected to the pieces she writes about. Art historians and critics don’t always take the time to understand the logics of craft materials, but Bryan-Wilson has a kinetic understanding of the work because she has learned how to do the processes herself.

OCYes, I really admire Julia Bryan-Wilson as a scholar because she is a maker and knower. She combines the kinetic knowledge of craft processes that Riley mentioned with academic research and writing. How do you see your own relationship with both writing and making?

SMWhen I’m quilting, I’m often talking to my friends on the phone, or we’re sewing together in the same space. I feel like I’m physically weaving or hand stitching the conversations that we’re having into the quilt. That is a sentiment I hoped to bring to the group as well—that the collective knowledge we crafted in the reading group meetings became a part of everyone’s studio practice.

DREW MAUDE-GRIFFINI make art because my words aren’t always enough to express my deeper feelings. I use artwork when I want the viewer to feel an emotion and believe an experience they may not have had. Sometimes theory can hit that same note.

OCGoing deeper into the specific texts, you all read the chapter “Queerness as Horizon” by Muñoz, which Soph mentioned earlier. He opens the book with, “Queerness is an ideality. Put another way, we are not yet queer. We may never touch queerness but we can feel it. The future is queerness.”1 I am thinking about Drew’s series, Crip Futures, from 2021, which explores what a future of care and access could look like through pieces that combine text with texture. What is the relationship between crip futures and queer futures for you, Drew?

DMGSomething that comes up repeatedly in the Muñoz text is the concept of straight time versus queer time. It reminded me of Alison Kafer’s crip time.2 Both queer and crip futurity hinge on the undefinable. Muñoz calls it the “no-longer-conscious and the not-yet-here,” taken from German critical theorist Ernst Bloch.3 Queer people and people with disabilities are operating outside of, against, or in spite of late-stage capitalism. We have a history of finding ways to survive through conditions that are not meant for our survival. There are deep wells of wisdom from people who have passed on. We need that wisdom to find our way into the future. For queer futures too, there is already a wealth of wisdom, but some of those experiences, like the AIDS crisis, have been taken away.

OCThough Muñoz orients toward the future, that horizon for him is connected to the past and present. Craft is often relegated to the space of the past via its association with tradition. At first queer theory and craft seem to be in tension, with queerness often about being on the outside of norms, while craft can be conservative. How do you explore these tensions?

DMGCraft has this traditional background, materials, and rules, but they can be broken so easily. For example, a queer approach to materials is being resourceful, using and reusing the materials around you.

OCRaye, I know that you also work in mixed media, so you are maybe less limited by the medium specificity and tradition of craft. Can you talk about how you got into using textiles?

RCI didn’t learn textiles from a grandmother or my family. That is an aspect of my life, even outside of my art practice, that I grapple with. A lot of family history and textile making traditions have been lost through colonization. An inherent part of using any traditional techniques for me is putting together that past with the future to move forward.

I actually started engaging with textiles in middle school when I taught myself how to crochet from a book at the Scholastic Book Fair, if anyone remembers those. Since then, it has always been a part of my art practice, but I try to blend everything that I’ve learned from different media into my pieces. That is what life is all about—combining all of our experiences. Obviously, I can’t force fibers to do something that is not in their nature, but I try to enhance it to the best of its ability. It’s a back and forth conversation between me and the fiber that I’m using.

OC I noticed several artists referenced quotes in their wall labels from Audre Lorde’s essay “The Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” from her book Sister Outsider. The repetitive motions of the body are so central to the process of creating textiles. Lorde defines the erotic as a deep, internal self-knowing that is at once embodied, political, emotional, and intellectual/poetic.4 Desire, for Lorde, is not just about sexuality, but also connected to one’s creative force. What role does the body play for you in your art practice?

RK Creating textile work, my body is a co-conspirator. For the piece Trans Flag , I wove it on a table loom. To create the pattern, I lifted and changed eight different levers with each pass and then pulled the beater. It is very physical work. The loom was my co-choreographer, but my body was a timekeeper. I can only do that kind of physical work for so long. The body serves as a reminder to take breaks and pull back to have time to think.

OC So often, craft processes are super physical and can be very tiring from those repetitive body motions.

DMG There’s a double-sided nature to it. There are laborious aspects of textile work, but there’s also nervous system regulation with those repetitive motions. I came to textiles because I wanted to make a large piece, but I was not physically up for making a large painting. I thought of my grandma, who had her own health issues. She crocheted all day long, accumulating squares and hats into a mass of crocheted things that had the same impact on me as a large painting. If I’m not physically able to go into the studio, what if I’m crocheting in bed instead?

OC Lorde writes that, “The erotic functions for me…in providing the power which comes from sharing deeply any pursuit with another person. The sharing of joy…forms a bridge between the sharers which can be the basis for understanding much of what is not shared between them and lessens the threat of their difference.”5 Collective belonging and queer relational formations also come up in several of the other texts you read. How is your art making practice or the pieces themselves an exercise in sharing joy with other people?

SM The active coming together with other queer artists who make textiles feels very erotic. It is an embodied experience to be exchanging ideas. One thing that felt so good about studying art in college was having access to a shared studio space where I had organic conversations with other artists. This was often a point of contention between me and an undergrad professor. He told me if I spent less time facilitating projects, I would have more time in the studio. In a way, I suppose that’s true, but the interactions were and are an inherent part of my process and why I make work—they are a resource.

Riley Kleve, Untitled 1-99, 2023. Photo: Olivia Comstock.

Riley Kleve, Untitled 1-99, 2023. Photo: Olivia Comstock.

RKOlivia, I like that you pulled this quote about joy breaking down differences. That is what I aim to do with my pieces that have a community engagement component. For example, with Untitled 1-99, I asked visitors to name pins seventy eight through ninety nine with what the pin would communicate for the wearer. I hope to deepen the shared well that we all draw from when we pick up a piece of fiber.

DMGWhen we were reading Lorde’s essay, it reminded me of Mia Mingus’s article “Access Intimacy,” which is about the joy when someone already knows what care you need. This inspired my piece Indisposable for the show. Recently, I met up with an old friend, and she was already wearing the same kind of mask as me. I didn’t have to explain that I’m still taking covid precautions. There was just the joyfulness of reuniting with a friend without any uncomfortable boundary setting. With Indisposable, I show how wearing a mask or having these N95 wrappers filled with glitter is also a celebration of queerness. The aesthetics of intimacy, camp, or any gritty part of queerness that we might separate from wearing a mask still exists within the queer disability community. The connection from that choice can be really beautiful.

OCWe are going to end by coming full circle back to Muñoz. What is your personal vision for a queer future?

RKOne where everyone’s needs are met, and there is abundance–where we can explore joy and creativity.

DMGMaybe it’s corny, but a queer future includes spaces like the Embodied Material reading group. We need community led spaces where together we can fumble through ideas that we’re not sure about yet.

RCQueerness should always be something that challenges and questions. I can’t imagine queerness being a completed project. It is always an ongoing process. Even though the queer future is undefinable in a lot of ways, it is one of safety and abundance, like Riley and Drew said.

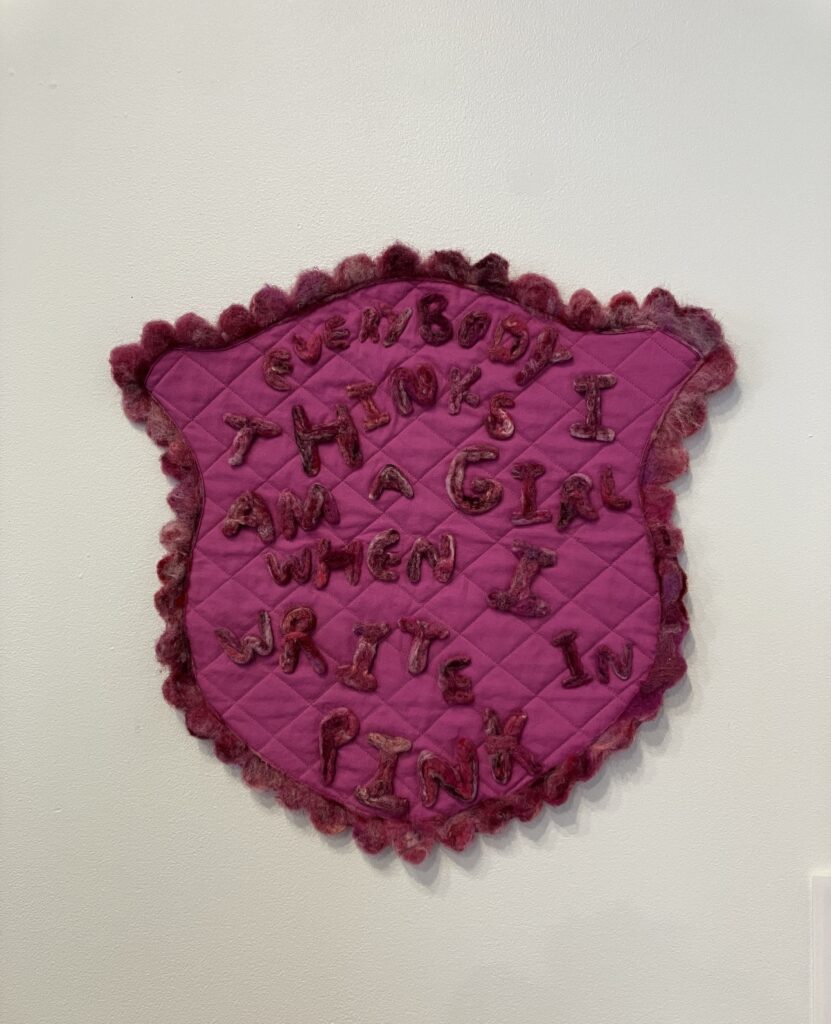

SMMy vision for a queer future is a horizon where trans kids are not only safe, but have the freedom to explore who they are without fear that any anti-trans legislation will prevent them from becoming who they feel most embodied.

reading list

- Allison Kafer, Feminist, Queer, Crip. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013.

- Audre Lorde, Uses of the Erotic: the Erotic as Power from Sister Outsider. Berkeley: Crossing Press, 1984.

- Hannah Baer, Trans Girl Suicide Museum. Berkeley: Hesse Press, 2019.

- Jeanne Vaccarro, “Felt Matters.” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 20, no. 3, (2010): 253-266. (Another article by Vaccarro on similar topics that is available for free online)

- Eds. John Chaich and Todd Oldham, Queer Threads: Crafting Identity and Community. Pasadena: Ammo Books, 2017.

- Jose Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: NYU Press, 2009.

- Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray: Art & Textile Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

- LJ Roberts, “Put your Thing Down, Flip it, and Reverse It” from Extra/Ordinary, edited by Maria Elena Buszek. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011.

- Mia Mingus, “Access Intimacy,” on her blog Leaving Evidence, 2011.

Embodied Material is on view at Fresh Eye Gallery through July 29, 2023. >>more information