The Ghosts of St. Louis’s Northside in Christopher Harris’s 2000 still/here

On memory and materiality, the specters of historical violence, and gazing with care on neglected spaces

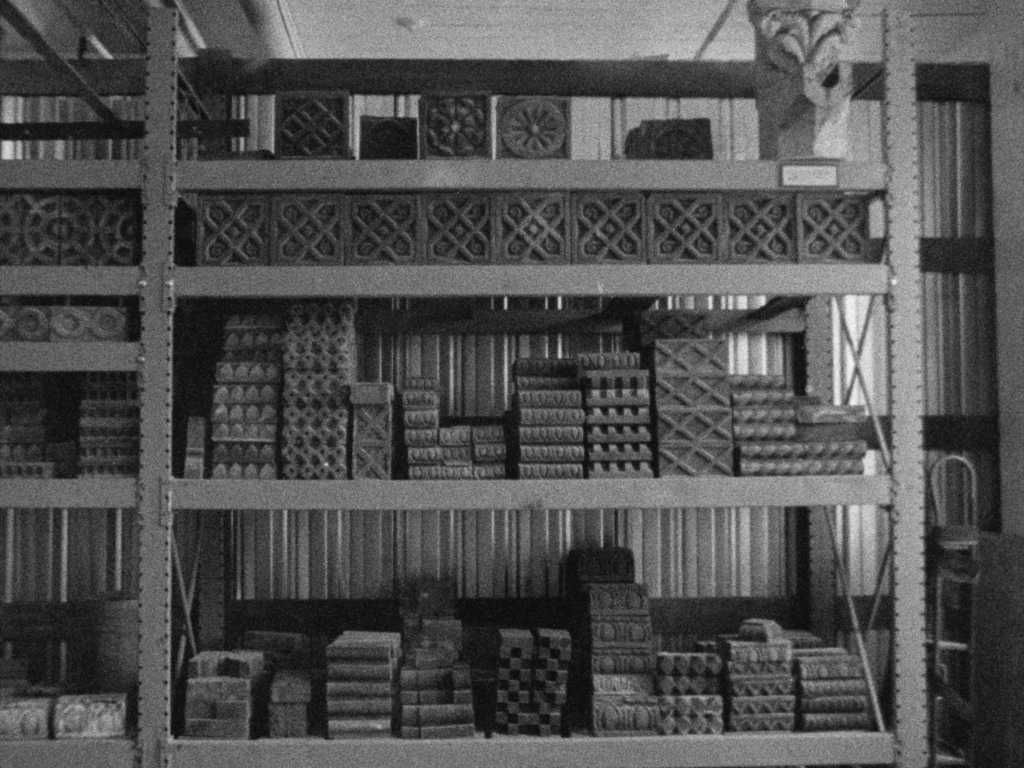

The architectural history of a once-great city lies packed into crates in a warehouse near Cahokia, Illinois. Molded cement pediments…ornamental cast iron…stone columns, friezes, reliefs, and figural sculptures…. The city of St. Louis torn down, pieced out into elements, cataloged, and packed into crates….

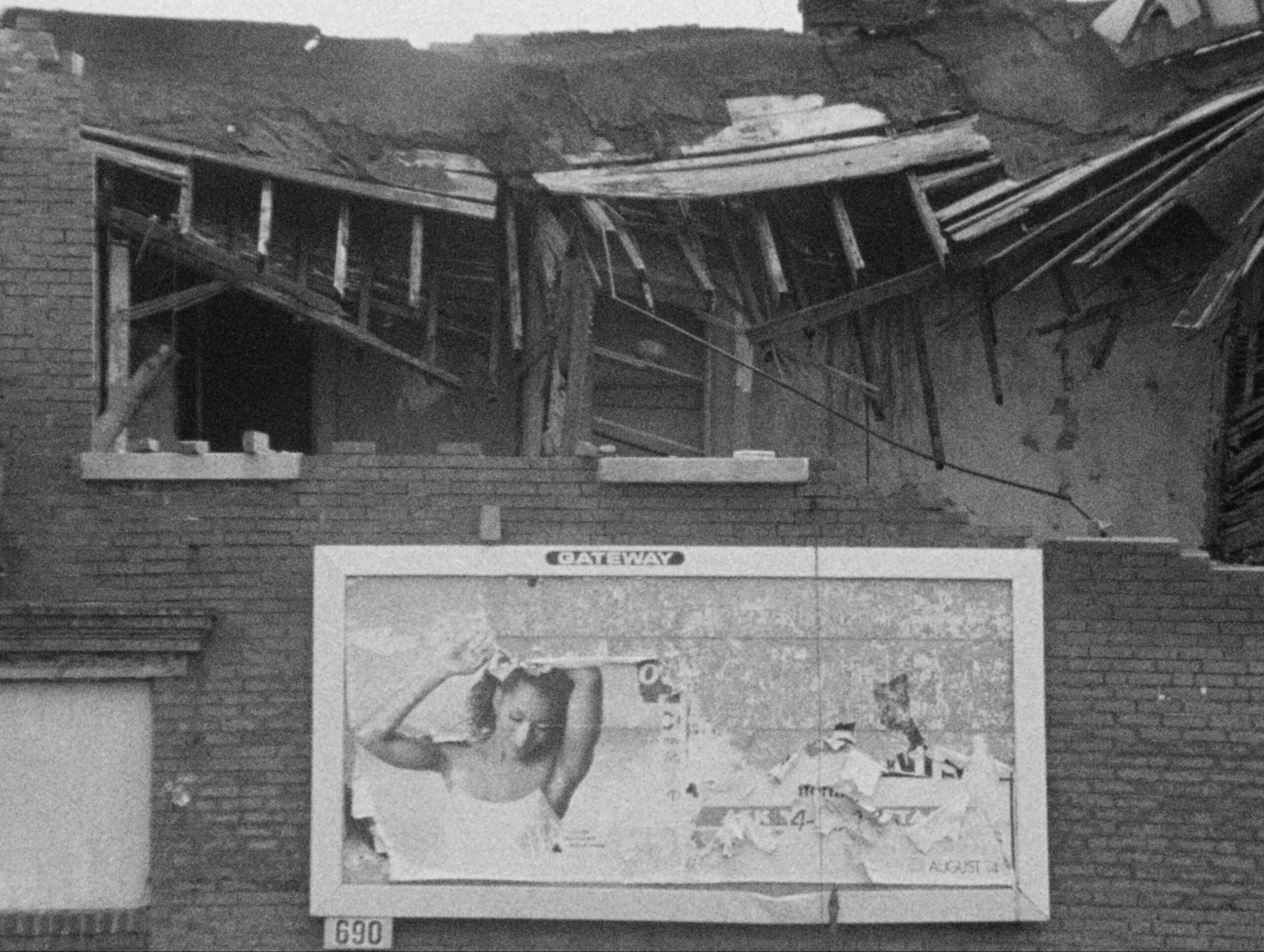

Across the Mississippi River, back in the city of St. Louis itself, the pieces of the past lie jumbled together and scattered around the foundations of the city’s thirty thousand vacant houses, their windows boarded up and roofs collapsed upon themselves. Many of these houses have been repossessed by the city and delegated to the St. Louis Land Clearance for Redevelopment Authority for resale; some can be bought for as little as a single dollar.1

So begins Walter Johnson’s 2020 The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States about the workings of racial capitalism in the making of the city. It was this same melancholy contrast between dilapidated buildings and their pristinely preserved fragments that I found to be one of the most poignant elements of filmmaker Christopher Harris’s experimental documentary about St. Louis still/here, completed 20 years prior, in 2000, and recently acquired by the Walker Art Center’s Ruben/Bentson Moving Image Collection. In still/here, Harris filmed the neighborhoods that he had grown up in and found deeply transformed in the late 1990s, upon his return to the city.2 By that time, St. Louis—a city with today one-third of the population of its highpoint in 1950—had become deeply associated with urban decline.3 Harris, now a professor of Cinematic Arts at the University of Iowa, has meanwhile created many more experimental films using a variety of approaches that are regularly screened and honored in contemporary film and art venues, but appreciation for the significance of this early gem continues to grow, including through its digital restoration by the Academy Film Archive in 2022. In this short piece, I provide a brief overview of the work and review some of the growing commentary on it. I also turn to the artist’s own words about the work’s themes, including from a conversation that I had with him earlier this year, as well as suggest a way of interpreting the film’s haunting techniques. As an art historian interested in specters of historical violence explored by contemporary artists and filmmakers, I was particularly drawn to the film for the ways that it generates reflection on memory and materiality and the politics of preservation of architectural sites and objects.

A black-and-white feature-length 16 mm work, still/here is mainly made up of static and roving unpeopled takes of residential and other abandoned and decaying structures and of entire boarded-up blocks and overgrown lots in the predominantly African-American group of neighborhoods that make up north St. Louis. While many shots frame individual residences, others are close-ups of building remnants or wide landscape tracking shots from moving vehicles. The film’s images linger on the physical remains of these ruined edifices’ interiors and exteriors, both in shorter shots of several seconds and more extended ones. A quick succession of brief panoramic views of St. Louis from a high vantage point in its downtown, mainly looking towards its north side,4 begin the film, soon giving way to mostly slower-paced still and moving ground-level shots of north St. Louis buildings and neighborhoods for the film’s remainder. These longer sequences begin with a shot of a building at the corner of St. Louis and Jefferson Avenues, the street signs one of a number of increasingly complex references in the film to its location, culminating in a dreamlike voice-over later in the film. The use of extended takes, some with a fixed camera, both with and without suggestive or disjunctive audio, is characteristic of modes of experimental film practiced in the wake of structural film of the 1960s and 1970s that produce deliberation on reality beyond the camera lens on the part of viewers. At the same time, Harris recontextualizes such techniques in this and other works by drawing on and dialoguing with a repertoire and history of African-American avant-garde artistic procedures across multiple visual arts and musical mediums, including those of the Chicago-based Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM).5

Within a few seconds of the film’s beginning, a voice-over begins of a character who the viewer imagines to be an architectural historian or documentary photographer, expounding upon the histories of labor and life behind the city’s built environment. The female voice declares,

We walk down the street, and we see all of these houses. And all these houses have some kind of brick. And you have to understand the magnitude of work when you realize that each one of those bricks was touched by a human hand. There’s no machine that lays bricks at this point. And you realize that every one of those bricks was put down by hand. A hand, a man that fought, fed, well, he worked, he went to bed, he had a family, he had a life, and this hand put this brick down. And you look around and you see all those bricks, and you realize how people have worked….

This moving extended commentary—which continues into the first of the longer shots of ruined buildings and neighborhoods—immediately sets up viewers and listeners to become acutely conscious of the absences that haunt the film (and which are accentuated by the film’s startling use of non-synchronous sound, to which I will return): of those who built and those who lived in these buildings and neighborhoods and especially, of those forced out of them, due to historical and economic processes and government policies that led to the emptying out of these neighborhoods in St. Louis and the dilapidation of these structures. In addition, this monologue disposes us to continue to reflect, as we watch the film, on urban, industrial, and architectural histories, those of race and racism, migration and immigration, as well as of urban heritage preservation, as they intersect in the fate of these remnants of buildings and urban districts.

Coinciding and in tension with the film’s bringing attention to absence is a strong sense of materiality and physicality in the way that the camera gazes at these structures and remainders. Asked about this emphasis, Harris commented,

When I think of childhood memories of growing up on the north side of St. Louis, what I think about is, in large part…the way that the built environment looked….Those are the things that really resonate for me, so when I see that kind of stuff…I’m really haptically transported in my memory. It’s a material memory, you could say.6

This sensitivity to the ways that historical and social forces have shaped material objects and spaces infuses the film, which, moreover, sets up a play between the materiality of 16 mm film and the film’s themes, critical to much of Harris’s work.7 The film seems to posit through this focused contemplation of architectural remains that something of the desires of the former occupants of these structures still reside in them, and that the film’s indexical imprinting of these objects and urban landscapes also contains their subjective imprinting.

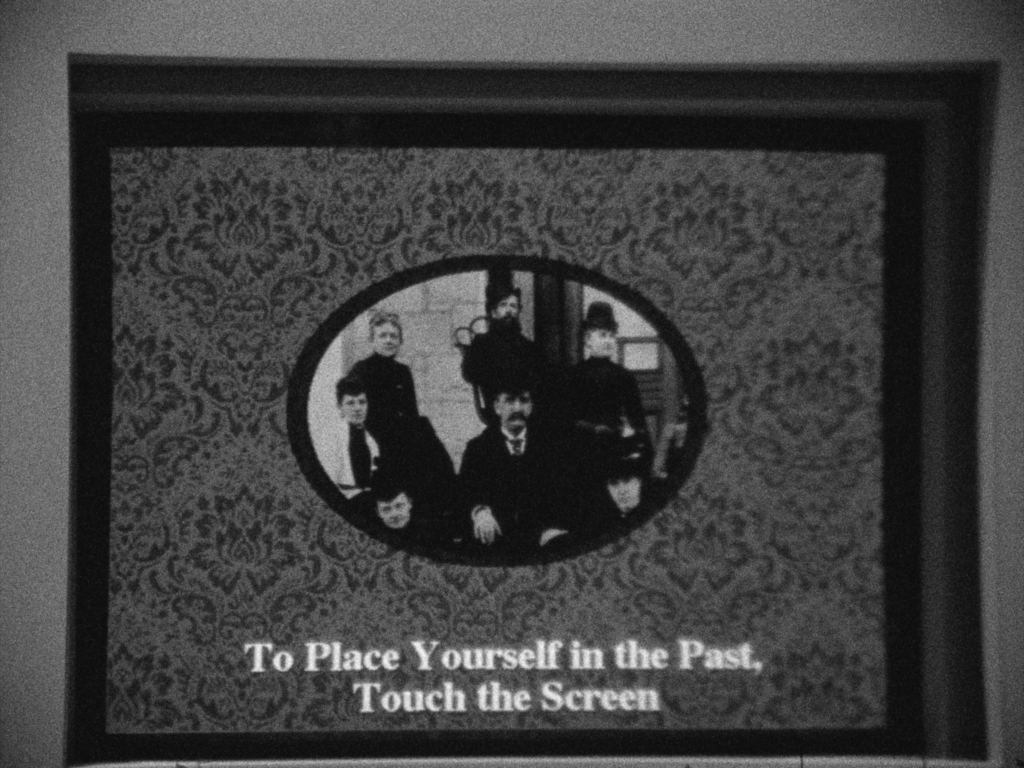

still/here also foregrounds absence in its aforementioned disjointed use of soundtrack elements that seems to evoke displaced inhabitants, as well as appropriated audio clips that allude to aspects of St. Louis’s intertwined urban and racial histories (for example, from the city Housing Authority’s voicemail message and lighthearted news interviews with developers discussing the convenience of suburban housing developments that allow residents to easily escape the city). Many scenes are accompanied by soundtracks of unanswered phones, doorbells, and footsteps, of what could be domestic activities, and other haunting non-synchronous sounds. This is carried out at times in an almost absurdist way, with such recurring, insistent sounds heard while the camera is trained on empty, crumbling building interiors or exteriors. True to Harris’s keen sense of historical particularity and the mnemonic capacities of material objects, sounds of old-fashioned mechanical doorbells and telephones resonate through these deserted spaces.8

This summoning through inexplicable sounds of the past residents of a place to remind those in the present of their existence is, of course, a description of the modality of haunting, as often described or pictured in literature or films. Along these lines, Harris’s techniques can be understood, in one way, in relation to the notion of haunting as conceptualized by Avery Gordon in Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. According to Gordon, haunting can be a means for thinking through the consequences of racial and other injustices. When unaddressed or unacknowledged, these injuries produce ghosts, whose arrival breaks down barriers between past and present and by means of which brutal histories can be explored. Gordon writes,

The ghost is not simply a dead or a missing person, but a social figure, and investigating it can lead to that dense site where history and subjectivity make social life. The ghost or the apparition is one form by which something lost, or barely visible, or seemingly not there to our supposedly well-trained eyes, makes itself known or apparent to us….9

Similarly, scholar Tina Campt’s method of “listening to images” that she has brought to bear on vernacular photography from neglected African diasporic archives to “reconstruct the subjectivity…of figures…essentially considered mute” is resonant with the film’s examination of urban ruins typically characterized as ones of blight.10

Commentators on still/here have remarked that the film calls forth a number of styles and genres from modern and contemporary film, photographic, and art history. The film’s richness lies in part in this simultaneous insistence on the material presences and absences of north St. Louis’s “ruins” and suggestiveness in facilitating connections with so many 20th-century histories, beginning with functioning as kind of a counterpoint to the “city symphony” of the early 20th century, one of the earliest genres of experimental film (exemplified by Walter Ruttmann’s 1927 Berlin: Symphony of a Great Metropolis), as scholar Terri Francis has discussed. Francis has also written about how still/here can be productively considered in relation to the genre of so-called hood films, and critic Nicolas Rapold has alluded to its connections with the stereotypical portrayal of urban decay in Hollywood productions and the apocalyptic destruction of cities in action films.11

An even more immediate reference is the photographic genre of ruins photography, which has focused, most famously, on sites in the city of Detroit.12 In contrast, however, to such mainstream representations of urban decay and especially to the voyeuristic attitude of “ruin porn,” Harris, by inserting the poetic words of unseen narrators and emphatic sounds of everyday objects and lives, instead gazes at these remnants, as he stated, with “love”:

It’s almost like when you have a dear relative who dies, you may cherish one of their possessions….I’m loving these spaces because I love the people who live there. But the reason the spaces look this way is because society, for lack of a better word, hated these people….[I]t’s like how [André] Bazin talks about the image as a fingerprint. These ruins to me are like a fingerprint of…social forces.13

These social forces, often explained as a combination of individual decisions that produced white flight and an inevitable drive towards suburbanization, must be understood, as historians like Johnson and Colin Gordon in his Mapping Decline: St. Louis and the Fate of the American City have shown, as the sum of decades of deliberate racist government policy.14

The other side of still/here’s shots of north St. Louis’s ruined buildings echoing with past histories and lives are the orderly, discrete remnants of the city’s architecture displayed and warehoused in regional museums and historical societies that the film also shows. In The Broken Heart of America, Johnson writes,

Of the city’s abandoned houses, it is perhaps fair to say that they are worth more dead than alive. The deep burgundy bricks…molded out of the clay from pits on the city’s Southside and fired in the kilns of its famous brickworks around the turn of the century, sell for fifty cents apiece today in cities like New Orleans and Houston.15

Of the sequences in the film picturing such museumified pieces of St. Louis architecture, Harris remarks,

There’s a kind of care lavished on certain artifacts and objects, but there’s a real disregard and a lack of care for African-American spaces…. A few blocks away, the actual spaces are allowed to decay, and they’re subject to a whole host of social forces that are a form of what is sometimes called slow violence…or much more direct violence.16

In turn, Harris describes his own empathetic consideration of these neglected spaces as a form of “carework”—using a term from Black feminist studies related to an “alternative epistemology” emphasizing social relationships.17

Like Kevin Jerome Everson’s films that show Black working-class life in the Midwest, or the work of the photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier who has focused on her family and community in deindustrialized Braddock, Pennsylvania, Harris’s film illuminates racial dynamics of disinvestment and development in postindustrial America, and is particularly apt for re-viewing in our current era dominated by discussion of the white working class and its turn towards right-wing politics. Everson’s films understatedly depict the craft skills and day-to-day lives of African-Americans in durational films set mainly in Ohio. Frazier’s works show not only the ruins of devastated Braddock and the environmental illnesses and indignities suffered by her family members and other residents, but also forms of resistance and solidarity and moments of everyday intimacy that take place in between. Harris’s film, for its part, through close looking and evocative techniques tells a story of the material traces left by Black Americans in St. Louis, of the spaces that they inhabited and continue to inhabit, and of how palpable histories are embedded within the city’s built environment. By doing so, it prompts viewers to consider American urban ruins with a historical gaze and a radical and political form of love.

Christopher Harris’s still/here will be screened in the Walker Cinema on Thursday, November 16, 2023, and will soon be available in the Bentson Mediatheque as part of the Ruben/Bentson Moving Image Collection. >> more information