Lies Like Truth

Nathaniel Smith explores the illusions and play on perspective in the two shows up in the MIA's MAEP Galleries through March 31: Brett Smith's cinephilic "Superimpostor" and David Bowen's trippy simulation of Lake Superior waves, "underwater."

I HAVE ALWAYS BEEN AN ADMIRER of the Minnesota Artist Exhibition Program (MAEP) at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. With its historic, encyclopedic collection, the MIA is the Met to Walker Art Center’s MoMA, so there is something particularly satisfying about the gesture of designating two galleries for the sake of showing contemporary local art in the MIA’s otherwise very traditional museum setting.

For this round in the exhibition season, the institute’s MAEP Galleries are hosting David Bowen’s underwater and Brett Smith’s Superimpostor. While each artist is chosen for inclusion in the program separately, careful attention is paid to how each gallery space will be filled and how the artists’ works will interact as a viewer steps from one room to the next. I suspect both exhibitions will be striking to most visitors, as new media work like Bowen’s nature-influenced machinery and Smith’s visual effects and set designs are not often found in local galleries. Such work is something of a departure for the MAEP program itself, but it’s a welcome change. New media artists have been increasingly visible on the national, and especially international scenes, but they’re still finding their footing in the typically conservative Minnesota art landscape.

That may change soon, though, as both underwater and Superimpostor deftly capitalize on the new media art’s ability to actively engage an audience with content that feels immediate and of the moment, which is exciting to view. Both artists exercise a clear, intentional visual language, yet neither offers much by way of specific narrative beyond the obvious feelings one experiences in the moment of seeing their work.

Observing and Connecting

Both Bowen’s underwater and Smith’s Superimpostor are relatively spare showings, filling their respective galleries with scale rather than quantity of objects. Smith’s exhibition technically contains three pieces, while Bowen presents just the single, titular work. Nonetheless, both galleries feel full, while allowing room for the audience to move around and between the pieces to find the best possible viewing angles. You can always discuss theory and context for any work outside the exhibition space, but the viewer’s physical presence in front of these large-scale, involved pieces is central to understanding them: you have to experience them directly. Just as one cannot fully explain what it feels like to be floating in a moving body of water, there is no way to convey in words the encapsulating sensation that comes from standing beneath underwater, below its rippling waves simulating the ebb and flow of Lake Superior. Likewise, seeing visual effects on a giant movie screen is entirely different than when viewed on a small screen, all the more so when you consider how the illusion of the acceleration of light in a wormhole is created in Smith’s Superimpostor. For each of these pieces, viewer’s own perspective becomes a necessary bridge between the works and communication of their message.

David Bowen’s underwater

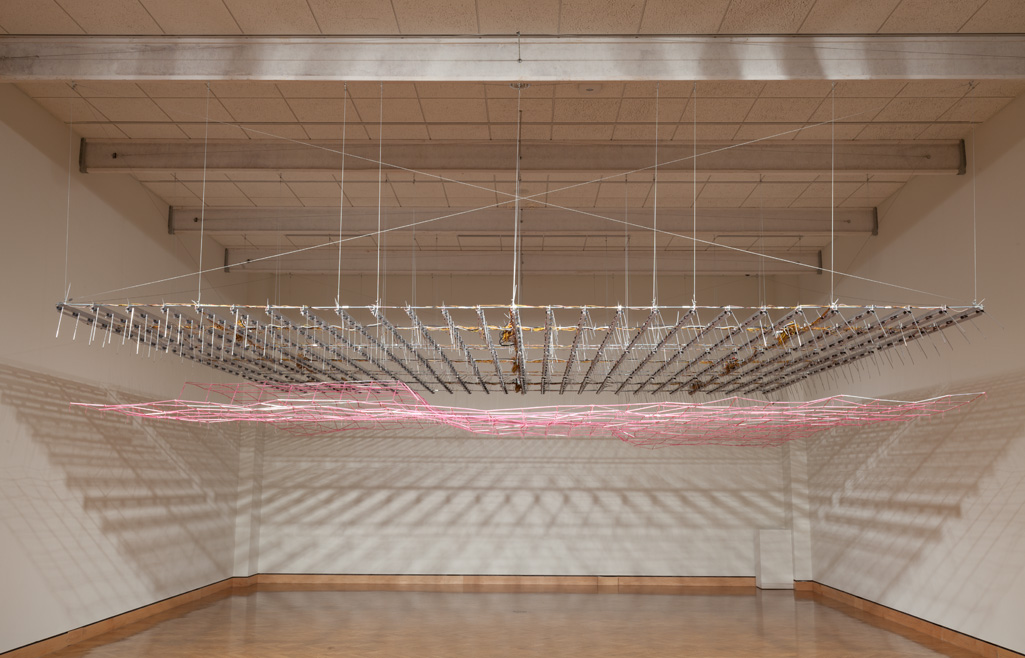

David Bowen’s underwater is the first piece you encounter as you walk into the MAEP galleries; it’s immediately and undeniably impossible to ignore. By collecting wave movements on Lake Superior and converting this data to a moving grid, Bowen seeks to replicate natural flow with machinery and programming. The actual structure of the piece consists of 729 points on three sections of frame which holds moving, mechanical arms. Each servomotor is connected to a thin filament which is then fastened to a pink fabric grid; the filaments move in unison, though at different undulations, on that interconnected grid.

Standing below his work, the overwhelming feeling is that of being underneath a body of water while waves roll over you. Shadows from the sparse lighting in the gallery seem to be an intentional element in the work, matching the movements of the vector-like grid, all of which combines to amplify the sense of being underneath something kinetic. The ambient sounds of the work become an element as well: the room is filled with the collective buzz of servos starting and stopping in unison. And just beneath that sound is a constant, slightly disquieting drone — the sound of many things moving collectively but not necessarily in concert, like waves or rain or swarms of insects.

Sound is far from the only physical experience of Bowen’s work; it’s impossible to ignore your own body, your own physicality, standing before such a large moving object, especially when that object seems, somehow, both alien and deeply familiar. Children in particular seem to be fascinated by underwater, a fact I noticed each time I visited the piece. Several times I saw a child reaching or even jumping up to try to touch one of the moving grid-points as it dropped to its lowest descent, stopping just short of actually touching it.

Walking through the exhibition with MAEP Program Director Chris Atkins, I noticed an interesting break in underwater‘s mechanical/natural illusion. As we passed under it, the back left corner of Bowen’s grid collapsed for a moment; the sound was like a jar full of pencils had been dropped on the floor. The grid remained motionless for only a few seconds, but it was long enough for me to fear the piece had broken. I started to ask Atkins what was happening, but before I could finish my question, underwater began moving again. He explained that the pause was just the end of the program’s cycle, a moment’s break before the rhythms began again.

Somehow those few seconds seem to me symbolic of the whole exhibition: we expect machines to run and water to flow, and yet it is in those moments when our expectations are not met that we truly see and appreciate the wonder in these everyday happenings. It’s in the moment of its interruption that we think to consider the simple elegance of a wave’s movement. In reference to his work, Bowen states, “In some ways the devices are attempting, often futilely, to simulate or mimic a natural form, system or function. When the mechanisms fail to replicate the natural system the result is a completely unique outcome. It is these unpredictable occurrences that I find most fascinating.”

_____________________________________________________

We expect machines to run and water to flow, and yet it is in those moments when our expectations are not met that we truly see and appreciate the wonder in these everyday happenings.

_____________________________________________________

Brett Smith’s Superimpostor

Look closely at Brett Smith’s Superimpostor, and it’s like you’ve stepped into another world. The gallery space is painted black, the work lit only by specifically-placed color LED lamps shining on each piece. The largest of the works, Hertzsprung, parallels Bowen’s underwater in that it was also created using mapped data, this time from the moon. Unlike Bowen’s work, though, Superimpostor is marked by an artificial calmness. With its undulations, underwater immediately makes its presence known, but the work in Smith’s exhibition isn’t so accommodating: the installation doesn’t move for you – you move for it.

The work’s name is likely a reference to the Hertzsprung crater, one of the largest on the far side of the moon along the equator. Lunar data is collected, then passed along a router which carves out four segments that replicate the moon’s surface. The real transformation takes place when the viewer stands behind the sculpted piece of Smith’s work (fittingly reminiscent of a drive-through movie screen); from that vantage point, you’re able to view the surface of the piece as if it lay before you on the horizon, instead of vertically, in front of you.

This attention to the audience’s placement is typical for Smith. He says, “My brain works in 3D, so I usually try to determine the impact that I want a space or object will have on the viewer (and myself), and then attempt to tailor that into a sculpture or installation that gels with some of what I have been thinking about.”

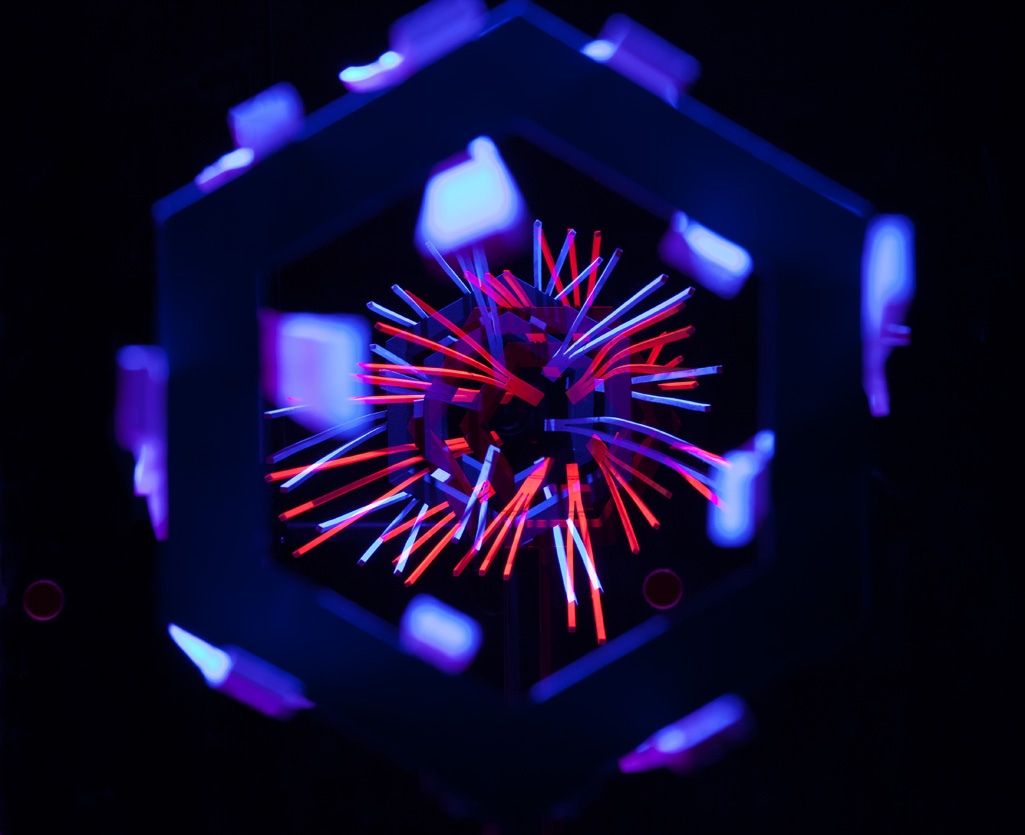

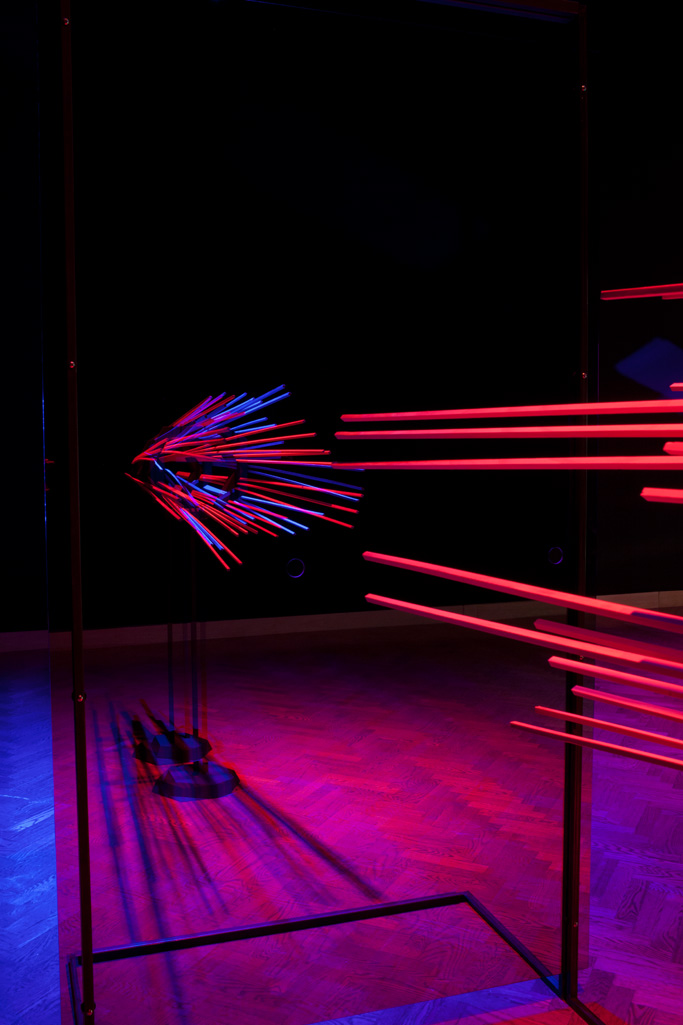

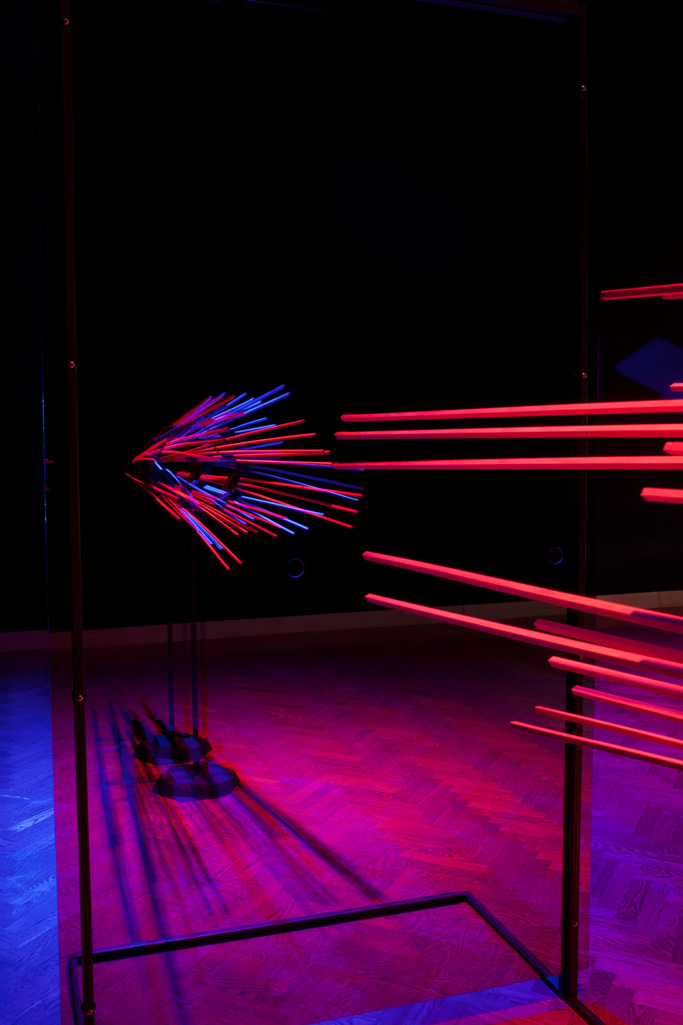

Towards the back of the gallery space, at the rear of the collective sculpture and lighting installation, is Superimpostor, Wormhole F and Wormhole W — one of Smith’s more convincing illusions. The piece consists of two carefully arranged mixed-media sculptures, situated on opposite sides of a reflective mirror so that they are perfectly aligned with each other. The sculptures are lit with blue and red, typical colors for creation of 3D film effects, to create the illusion of a three-dimensional wormhole on the mirror when you stand just so. This illusion is similar to Smith’s other multimedia installation, Superimpostor, Console 5 and Console 6. While Wormhole seems rooted in science fiction wizardry, the visual effect of Console 5 and Console 6 seems to harken back to Cubism. In the Console pieces, the use of blue and red has less to do with 3D glasses and monster movies than with color theory and opposite ends of a color wheel. And while both sculptures on either side of the mirror visually merge into a single “flat” picture, the effect of the sculpture/mirror illusion also changes the actual composition of its pieces before your eyes, morphing content of what you see in front of you. Through careful arranging, Smith effectively hides the support beams of these shapes, creating a floating purple (or turquoise, depending which side of the mirror the viewer stands) squared shape; what you see is different from the wooden form in front of the viewer who’s not looking at the work in the mirror. This kind of trickery, both the illusion and the breaking of the illusion, seems to be the crux of Smith’s work.

Brett Smith has very clear answer for me when I first ask him about the meaning of the show’s title, Superimpostor; his subsequent elaborations on, though, are many and appropriately vague. But that’s as it should be. After all, if the work is themed around imposters, then it stands to reason that what is on the surface cannot be immediately trusted. Smith mentions the very obvious influence of science fiction, and his admiration for the craft of creating worlds from low-tech materials and on-camera trickery. He also makes the interesting observation that once the trick is revealed, there is an endowment of power (knowing a magic trick for example makes one a magician) from the creator. Smith elaborates, “In the final version of Superimpostor I wanted to create an installation that would show the behind-the-scenes soundstage of my own nonexistent film — letting people see the illusion, see how the trick works, then break the image and hopefully drop into the fantastic because of it.”

Smith says he’s interested in science fiction fan culture, and what it means to a person’s identity when they are able to recreate the very illusions that first drew their attention to a favorite movie or comic-book character. His investigations play on the tension of revealing what’s going on behind the curtain – he’s empowering the audience, by breaking down the way special effects-style illusions are created; at the same time, he’s also dismantling another illusion, that it such tricks are inherently fascinating, or that they are extremely difficult/impossible to create by oneself. Given his transparency about the trickery deployed, Smith’s work feels less like a deception than it does a playful reminder to question the vagaries of perception, and an invitation to follow a continued investigation of the real.

Suspension of Disbelief

Although very different types of work, there are several connections between Bowen’s show and Smith’s that are readily apparent. Neither artist’s work is diminished by the fact that it’s quite clearly not the thing being referenced: that is, underwater does not literally look like water, nor does the rectangle of carved material in Hertzsprung perfectly imitate the appearance of the moon. Instead both artists play on the viewer’s perspective, calling to light the collusion between artist and viewer required for the suspension of disbelief by which the illusion works. Both exhibitions skillfully give hints and options, allowing each viewer – by virtue of their own perspective and angle of approach – an opportunity to reassess the pieces’ small wonders and impossibilities, in the process, maybe also reacquainting themselves with what it means to be familiar with our world.

_____________________________________________________

Noted exhibition details:

The current MAEP exhibitions, David Bowen: underwater and Brett Smith: Superimpostor, will be on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Art through March 31. Admission is free and open to the public.

_____________________________________________________

About the author: Nathaniel Smith is a Minneapolis-based artist, curator and writer. He was one half of the team that founded and directed The FUTURE PRESENCE Gallery from 2010 until the Summer of 2012, as well as the curator of the FREAKONOMIQUE Experimental Music Series. He is a little too good at talking about himself, and remarkably bad at writing about himself. His personal work can be seen at www.everythingalwaysdripsdown.com