Skate and Listen: A Conversation with Tetsuya Yamada

From skateboarding in Tokyo to a mid-career retrospective at the Walker Art Center: the sound of ceramic, wood, and concrete

Most non-skateboarders would not think that listening is something that skateboarders pay much attention to. In fact, listening plays a huge role in skateboarding. The skateboard itself is a mobile percussive instrument, like a drum. The rumble of rough asphalt or cracked concrete creates a series of sonic vibrations that, for the skateboarder, fuses aural and corporeal experience. We feel this sound in our bones. This noisy movement may often be a racket for the lay listener, but when I hear the sound of another skateboarder nearby, my ears perk up: this is an immediate friend, someone with whom I share a rarified language of spatial pathologies animated by sound. We connect to the world in a certain way that few others do. Skate-able spaces, be they wooden half pipes, concrete bowls, tiled plazas, or painted curbs with a familiar patina of slide-and-grind marks, invite performance and reverie. These are places that are redefined through skateboarding, where friends are made and a non-verbal, albeit clamorous, language is shared. Skateboarding is a practice of emphatic engagement.

Part of this awareness of listening as an act of empathy informs Tetsuya Yamada’s mid-career retrospective, titled Listening, at the Walker Art Center. These airy spaces filled with delicate objects and shimmering surfaces of knotty density but utter clarity invite empathetic connection. Imagine the different sounds that wood makes when bent, the creak just before it breaks, or the warm thud when struck. Porcelain rings when tapped, and clinks beautifully, but only once when it cracks. Empty cups invite our similarly cup-like ears to hear their whispering hum in space. All concave spaces have a sound, and those sounds are different if they are ceramic, wood, or concrete, proving that the space between our ears and those surfaces is not empty, and that materials matter. If you listen closely, you experience it fully. Not inert, these spaces roar. Recently, Tetsuya Yamada and I sat down over a Zoom call to discuss his roots in skateboarding in Tokyo, and how those unexpected and delicate threads resonate through his practice as an artist in Minneapolis.

Ted BarrowIt’s always exciting for me to talk to an artist who has a background in skateboarding because I think skateboarders consider texture, surface, spatial movement, and technique in a very particular way. So how and when did you start skateboarding?

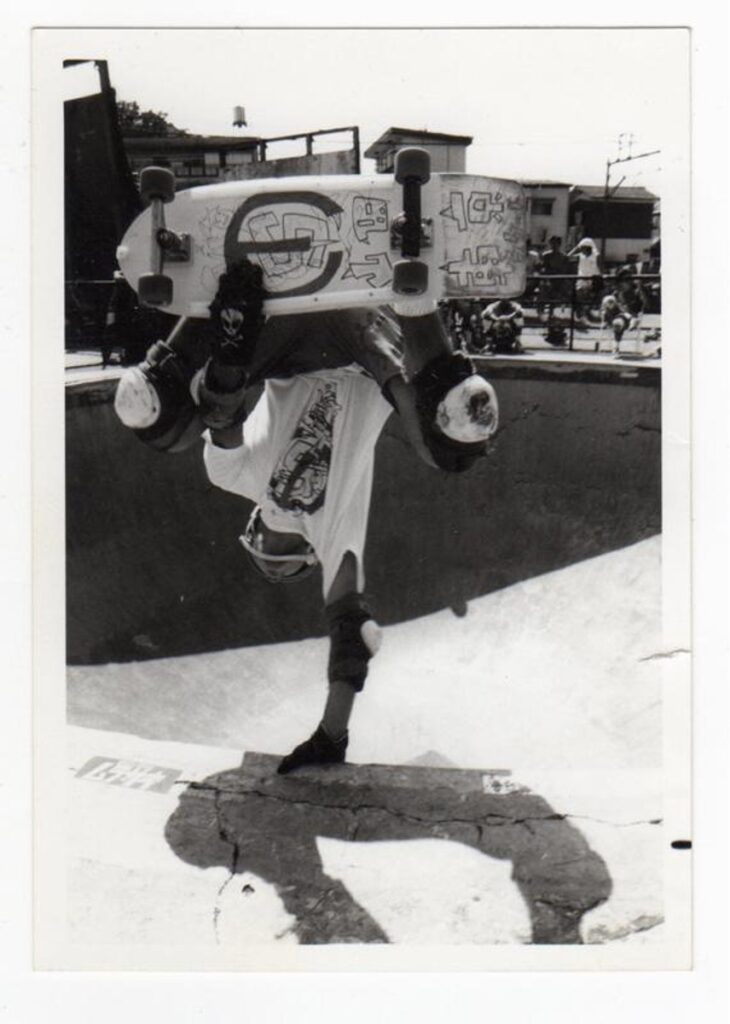

TETSUYA YAMADaWhen I was a little kid, I was into baseball. I lived in the outskirts of Tokyo. This is the early 80s if not late 70s. We had this batting cage that my father often took me to, with a go-kart track around the batting cage. The owner also built a concrete bowl, and one half pipe, and then one metal ramp. At first I went for the batting cage, but then I started to see this small group of people on Sunday skating the bowl. What I was really attracted to was the color of the Pro-Tec helmets, and then like their pads. Those kind of satin, shiny blue, yellow, and red. Do you remember Mad Rats, the pants?

TBYeah!

TYMad rats, those pants, half split, colored yellow, and green, or whatever. Those shiny ones, and then the graphic of the skateboard, color of the skateboard wheels.

TBWhat color were the skateboard wheels for you back then?

TYYellow, green, red, really big and round ones.

TBBy the time I started skating in the late 80s, skateboarding fashion was taking its cues from volleyball or something at the time, because everything had these neon geometric patterns everywhere, whereas the board graphics seemed influenced by Pop Art.

TYThat really excellent point because when I think about that kind of experience, of seeing those colors, and the graphic design and everything, it makes me think of Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes. I loved the Mad Rats. There’s a little diamond logo. It was black and white patched on the front part, and those pants had a pad on the back. People wearing big pads and all that helmets. It was just really fascinating.

TBIt’s almost like baseball doesn’t stand a chance next to Mad Rats.

TYNo! So that was the first sensation. Then eventually I thought, “I want to try!”

TBIt’s interesting that it began at a baseball field where there was a track, a half pipe, and a bowl. I know that after World War II in Japan, there were all these American activities being exported.

TYAbsolutely. Cars and everything.

TBSo were there local pros? I watched “Loveletters to Skateboarding” on Japan, and there’s this cool rivalry between Nishi and Aki.

TYOh, sure. I knew both of them. Nishi actually died early when he was so young. I have a couple of photos that he took.

TBOf you?

TYYeah.

TBOh, wow.

TYSo, that’s always my treasure. Nishi, his nickname was Devil Man. We had a cartoon character called Devil Man, which was also kind of interesting to think about: “Why is a Devil Man a good superhero?” Okay, so Nishi and Aki Akiyama, who’s still around. He’s very much a forefather.

TBHe seemed like he was definitely more of a 70s, Stacy Peralta-type skater…

TYI do remember in the 80s, Del Mar’s contest when Hosoi wins over Tony Hawk. That’s the time we watched and got like, “Wow, these are American Pros.” I still love how Hosoi skated in that video. He doesn’t change how he skates.

TBIt’s interesting that there are these pairs, the Tony Hawk/Christian Hosoi, or maybe Stacy Peralta/Jay Adams, Aki/Nishi binaries. It’s always the clean cut, squeaky clean person, the face in professional wrestling versus the bad guy, Devil Man, the heel. The hero and the villain.

TYThat’s interesting.

TBIt’s almost like the difference between Florentine or Venetian painting. Florentine painting is about line, Venetian painting is about color, about texture, or Delacroix versus Ingres, or whatever, Picasso and Matisse. There’s always these binaries that help us find our way into this work.

TYAbout the Christian Hosoi and Tony Hawk binary you mentioned: I feel like I can identify more with the Hosoi side.

TBIs what you relate to with Hosoi, is it because he’s associated more with beauty and form and style versus Hawk’s technical complexity?

TYTony Hawk is athletic, and Hosoi is about attitude. Although back then, compared with the rest of the world, skateboarding itself was so much about attitude. People today might see it as more athletic, but back then it wasn’t really about being an athlete, but it was more an outlet for the youth where they find that place where they can belong, and have similar values and so forth.

TBHere’s a ridiculous question: Is skateboarding more Duchampian or like Brancusi? Is it more conceptual or textural?

TYThat’s a very interesting question! I think Duchamp and Brancusi are very different, but they are very connected by the same spirit. So, those two are hard for me to split. I can definitely talk about Duchamp’s position against the art world. When he started doing Readymades—well, specifically, Fountain was submitted for the Society of Independent Artists, 1917. The hanging committee basically didn’t display the work because they didn’t see it as art. His point was, really, he didn’t want the aesthetic to dictate the artwork. So he was really against this authority in art. So that is really the spirit of punk, a similar spirit to skateboarding.

TBIt’s so interesting to me that in the late 1940s, you have this prototypical bowl course being built, or imagined by Noguchi in his contoured playgrounds. You also have the modern corporate plaza coming out of Mies van der Rohe in the late 50s early 60s. Think of the Seagram Building, these grand open plazas with exceedingly minimal forms where the materials themselves matter most. Modernism at its most conceptual and commercial in the mid-20th century ends up creating the most ideal playground for skateboarders.

TYGrowing up in Tokyo, at night it was pretty desolate. There were less people late at night. Security was a lot less aware of skateboarding. So we could go out at night to those places. It just really was such a liberating feeling. During the day, that space is really filled with business people and all kinds of people. Then you go there and when it’s quiet, you feel like you own the space. That was a really fantastic memory.

TBYou feel this sense of just belonging to a place and making it your own, and finding those angles, and feeling the surfaces, and discovering the right approach to the ledge, to the bank.

TYIf doing something during the daytime is the A-side, we lived in the B-side. There’s a whole other world on the B-side that A-side didn’t have.

TBDo you think part of your artistic practice comes out of that haptic tracing of skateboarding?

TYTactility and tracing probably might not be quite so close to each other, but I can definitely relate to the sense and understanding of space. These miniatures, the model, it’s not the way I would practically design a skatepark today if I were asked. It’s more to do with the memory of past experience.

TBIt just seems to me that it’s impossible to think of this without a skateboarder’s sensibility, looking at that volcano and then the shallow bowl with the lip around it. You would just imagine that the volcano creates a centrifugal spatial movement. You’re going to be coming out of it.

TYRight.

TBWhereas the concave bowl creates a centripetal movement inwards, right?

TYYes. I don’t know where that shape is coming from because I don’t know if I really skated that kind of volcano, but I think I must have looked at it. It’s a special feeling.

TBSomeone who doesn’t skate might just see the nice juxtaposition between those two forms, but there’s this other intense engagement that a skateboarder would have by imagining what it would feel like to roll through that space.

TYIt’s weaving those two things: a skateboarding memory plays into it, and a painting composition with all those formal elements.

TBI just want to highlight this because I really love knots. Again, and I’m going to credit skateboarding, but it’s probably just that attention to the surface and the sheen, and how different that the experience of this work would be if it were matte, you know?

TYThe coil of clay gets stretched and creates a tension, and then has that clustered density in the core. The idea of containment, that’s loosely what I was thinking about. The glaze is, of course, important because depending on the glaze, you can really emphasize the form. The process is rather quick. I take time to roll the coil nicely, but then once I start, it’s quick. It’s almost like cooking. Once you start to put that on the hot pan, it’ll be done quickly, and you have to stop because otherwise it will go in a different direction. You have to capture the freshness. When I’m making these series of knots, if I start all that thinking, the clay sets differently. I don’t want to retouch the clay. I don’t want to redo it. I never thought about it, but until you spoke about this connection, it’s almost like, “Oh, I did it this way. Next time I’m going to put my finger like this, here.” It’s almost like trying to learn a trick, you know? Because when you do tricks, you don’t have time to think about it. You have to do it at the moment. So that’s a similar way to how these knots were made.

TBIn skateboarding, every time you fall, you’re overthinking it. The moment that you actually land the trick for the first time is the time when your mind is totally clear.

TYOh, yeah.

TBYour mind is empty. Then, the challenge is to do that every time after.

TYNo, that’s good. Sometimes I think that back then, street skating, you go out at night, it’s like a blank canvas. You can do anything. You have to discover things because there weren’t any skate parks back then, so you had to find and discover all parts of the city. “Hey, I saw this and we’re going to go back,” and that sort of thing. The creativity really applies to skateboarding as well.

TBHow would you like audiences to experience your work?

TYThis upcoming show at the Walker is titled Listening, which comes from how I work with clay. I need to listen to clay because these natural craft materials—clay, fiber, wood—all have their own properties. Each has its own behavior. So you have to really understand. Another way to say it is that you have to really listen, otherwise you can’t force it. Otherwise it doesn’t really work.

That’s how I learned to work with clay: I need to listen. What is happening? What might be next? I need to really pay attention to that process of listening. So what about the art? It’s about listening rather than the art as, quote/unquote, “expression,” putting your voice, putting it to your expression, sharing your thoughts. So I thought, “Oh, that could be a kind of interesting approach to suggest. Rather than art as an expression, but art as listening?” I was really fascinated with that idea. What do I expect from the viewer? I would be really thrilled if they can listen to themselves through my work. In a way, it’s a little romantic.

TBSo listening is about being more gentle and open, compassionate. It’s not just about the making and the materials, but it’s about imagining what delicate sounds these objects would make when you’re near them. Especially with concave, dish-like forms, cups—they have a sound. You can imagine that, and imagining that sound and listening creates an empathetic connection to it.

TYEmpathy, yeah. I like that. Empathy.

TBIf you see something that’s skateable, you also feel this empathy towards it. You can imagine yourself in there somehow, on its surface, in that thing. It’s driven by this desire to live more intensely within the environment, right?

TYI know what you mean, but there’s also a lot of harm that probably happens to the edges. You skate and damage things. It’s a little more of a contrast.

TBThe art historian in me wants to preserve and ensure that the experience will be as intense for anyone as it is for me by not tampering with the work of art. The skateboarder in me is like, “No, this thing has to be used.”

TYAbsolutely! If I see some elements in the city where I can see how a skater has been really grinding here, is it vandalism, or what? At the same time, if you design this way in an urban society, you have to accept that. That’s how I also see it. You can’t try to avoid it. Let them do it.

TBHow do you feel about the idea of people using actual Noguchi plazas as skate spots?

TYI would really want to ask Noguchi about how he feels.

Tetsuya Yamada: Listening will be on view at the Walker Art Center January 18-July 7, 2024. → More information