Book Review: “Miniatures” by Norah Labiner

This review first ran in Rain Taxi, an Alternative Press Award-winning quarterly magazine published in Minneapolis.

Rain Taxi publishes reviews of literature from all over the world. It’s one of the few magazines that regularly cover poetry as well as fiction and nonfiction, and will have on its list of contributors in any issue fascinating writers from all media who are writing on the work of their peers. You can subscribe to Rain Taxi, or find it at most bookstores. Rain Taxi also organizes readings and other literary events around the Twin Cities. For more information about Rain Taxi, visit their website at www.raintaxi.com .

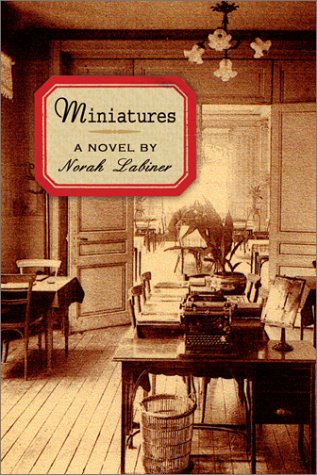

Miniatures, by Norah Labiner

Coffee House Press ($23)

Liar, liar, pants on fire. One wonders if the burning is the cause or the consequence of pronouncing a falsehood. Is the fabricator born warm with a desire to embellish, to add or delete, to outright change history? Or does the candle catch only after being caught in the act? Fern Jacobi’s a liar, and she tells us so, looking us straight in the eye. But does she lie or truth-tell in this admission? As she warns the reader from the outset of Norah Labiner’s second novel, Miniatures: “How can anyone ever trust a storyteller? Let me tell you that from here on trust neither the truth-teller nor the liar; choose neither heads nor tails, rely entirely on your own intuition and cast the odds aside.” (17)

Miniatures contains endless considerations about the nature of storytelling, of identity, of language as mediator and creator of experience, and of time and choice, providence and responsibility. There are constant references to other writers, history, parts of speech, and the alphabet. And, oh yeah—there’s a plot. The 21-year-old American Fern deports herself from a real or imagined love affair to adventures overseas, arriving by coincidence or Fate to houseclean at Owen and Brigid Lieb’s Ireland home. The Liebs are both writers, as was Owen’s first (now departed) wife Franny. Fern stays on as her cleaning duties morph into roles of companion, witness, confidant, and participant. Hinging many of the dramas here is a stack of purloined letters, which invokes other correspondences, fictions, biographies—Edgar Allan Poe, for instance, in passages of hyperbolic, self-pondering monologues, a mood of intrigue, and an unreliable narrator’s point of view.

Marcel Proust visits too, as a fictional character as well as in the debate, begun by a real-life critic, as to whether his work is stylistically more microscopic or telescopic. Labiner engages the debate by vacillating her own descriptions between the minute and the cosmic. Sometimes it’s hard to tell whether the world is seen as a stark single letter or as the vast starry history of written civilization. Or weirdly, resonantly, as both: in Miniatures the letter, in both its alphabetical and epistolary versions, forms the vehicle, the vessel, the vein by which the blood of passionate storytelling flows.

Labiner’s perspective-within-perspective, letters-within-letters, metafictional, time-shifting, referential style isn’t for everyone. For those who don’t enjoy the lyrical, playful accretion of, say, Woolf, Borges, or Robbe-Grillet, the narrative may feel tangled, repetitious, obscure in literary allusion, and overwrought. For those who do, however, the text buoys rather than drowns with life’s intricate puzzles; it achieves a startling sense of integration despite the sheer plethora of ideas, biographies, locations, characters, and letters. Miniatures is brilliant in the way that a shiny, invigorating lake is brilliant: because of its depth, because of its oxygenation, and because the multifaceted eco-system that feeds it moves vibrantly beneath its appealing gleam.

So many possibilities are held in suspension in this novel that the polarities of the human world—sweet/salty, waking/dreaming, past/present—cease to compete: all “or”s become “and”s in the larger pattern. This is a feminist notion from goddess cultures which value inclusivity, shapeshifting, nourishment, and (before it was invented) unified field physics. When Fern advises us, the readers, to refuse either of the two proffered extremes and instead to follow intuition, she is using the language of wise women who cast circles and spells, who listen to the cycles of self and season more than to the laws of men. She’s also inviting us to bring our own sorcery to the tale, like Alice who drank from the make-me-small bottle so she could better experience the awe of the world. Neither microscope nor telescope, Miniatures is rather a kaleidoscope: bright magic.