An Idea of a Cow

On visual poetry, the interplay of language and culture, and how allowing space for miscommunication can give rise to new meanings and unexplored paths

Written words don’t have any direct correlation with the thing they refer to; for instance, there’s nothing “cow-y” about the word “cow”. The pipe of Magritte’s The Treachery Of Images comes to mind, a tongue-in-cheek reminder that a reproduction of an object is not the object itself. In the case of words, nothing in the “drawing” of a word, plain and simply written, brings any characteristic of the concept it alludes to.

From the start, we can say that our relationship with words and the concepts they refer to is a complex one to reflect upon, something that involves our very subjective relationship with the concept itself, incorporating elements of our personal experience, the context we grew up in, and so on. A word is, then, a code, composed by another one—in this particular case, the Roman alphabet—drawing its meaning from elements such as context, memory, and culture.

With this reasoning in mind, the idea of a 100% seamless communication of concept, under all those variables, could seem unattainable. After all, if every concept carries a degree of subjectiveness to every person, how can we be certain we mean the same when we communicate with one another?

My mother grew up in the countryside and used to steal milk from the neighbor’s cow with her sisters. She would lure the cow with salt and molasses to the fence, milk the cow through it, and drink the milk right then and there. I grew up more of a city rat and didn’t have those close up interactions with farm animals. My idea of a cow is certainly different, and can veer first to the cleaned up, edited, and properly placed cow mugshot on my milk carton.

This juxtaposition of my mother’s stories and mine serves as a reminder when I get to reflect about the notions of meaning and context. Like Magritte’s pipe, my cow analogy serves me as a reminder that a word is not a static entity with a definite meaning, but a boundless, pliable one that may evoke different meanings to each and every one of us.

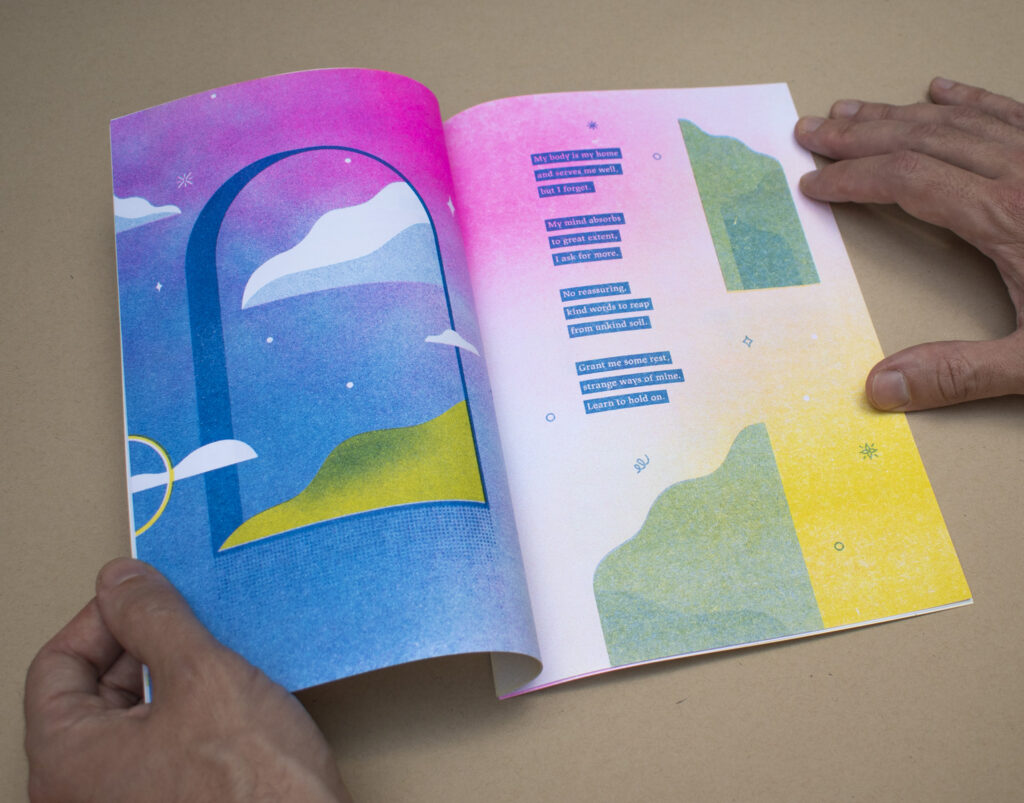

María José Castillo, Ineffable, 2022. Photo: María José Castillo.

María José Castillo, Ineffable, 2022. Photo: María José Castillo.

María José Castillo, Ineffable, 2022. Photo: María José Castillo.

I think that there’s something romantic and utterly frustrating about having to choose the perfect words to encapsulate a feeling. The concept of ineffability, one that refers to ideas that are difficult to put into words, intrigues me.

I wrote and illustrated a poetry zine, titled Ineffable, to give myself the challenge of tackling concepts that are difficult to explain by their nature, such as shame, fear, and insecurity.

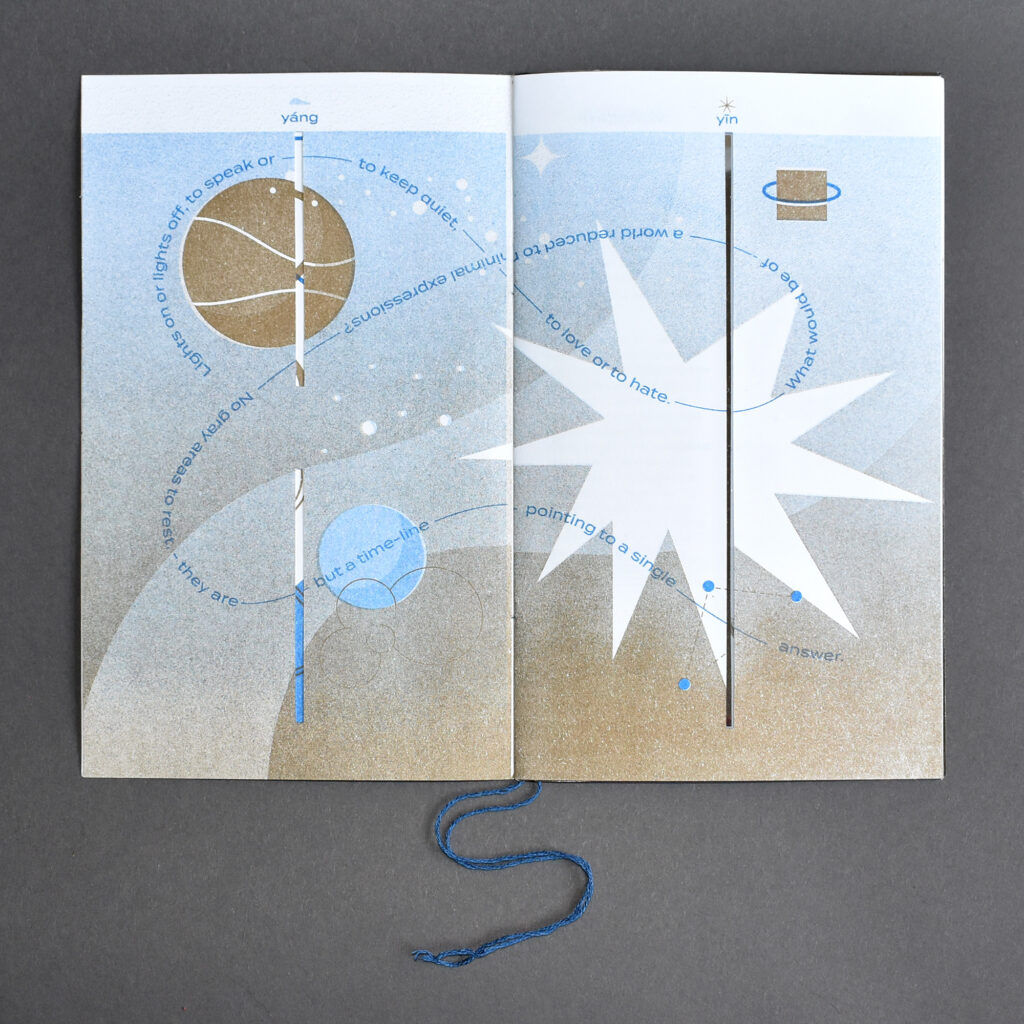

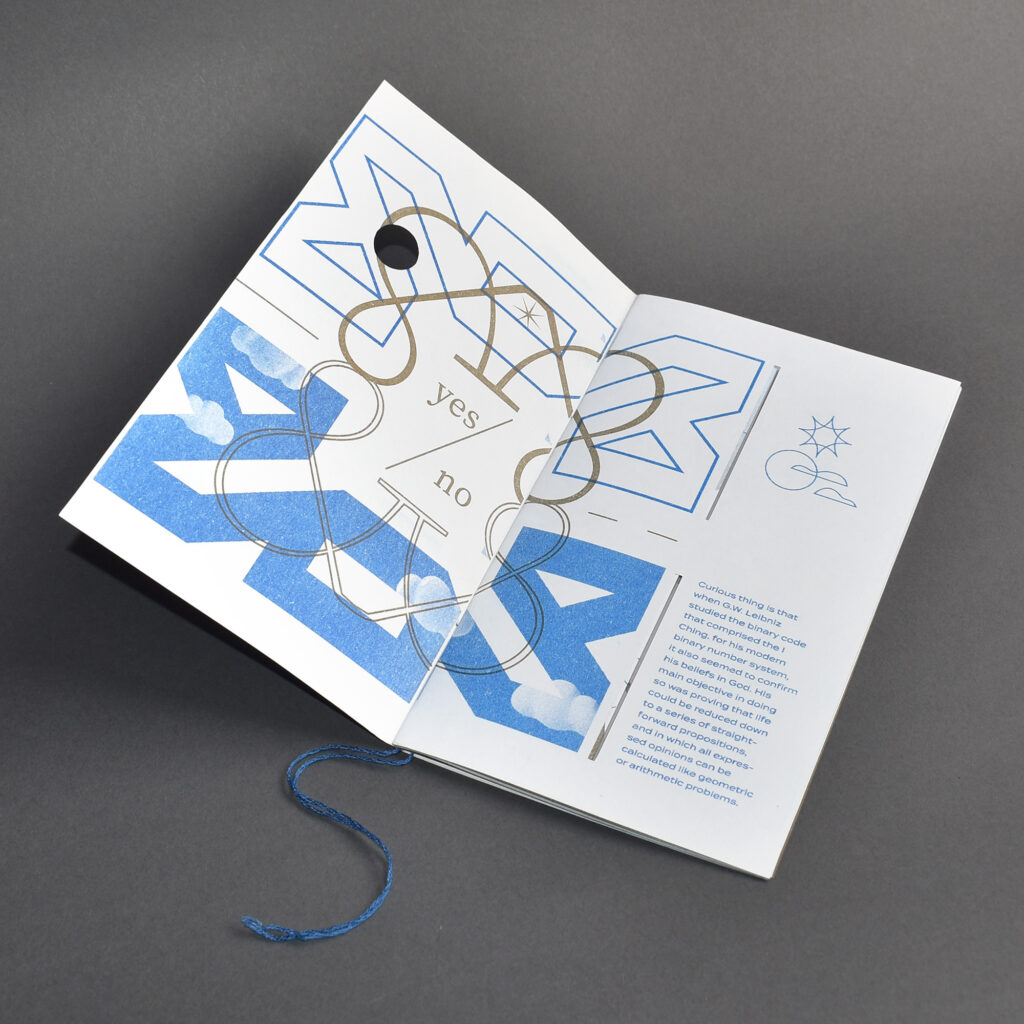

With another poetry zine of my making, titled The Yes and No Book, I examined the concepts of dichotomy, decision making, clarity and obfuscation, light and darkness, fate, and chance. I added a reflective paper insert and handmade die-cuts throughout to further explore these terms.

María José Castillo, The Yes And No Book, 2021. Photo: María José Castillo.

María José Castillo, The Yes And No Book, 2021. Photo: María José Castillo.

María José Castillo, The Yes And No Book, 2021. Photo: María José Castillo.

María José Castillo, The Yes And No Book, 2021. Photo: María José Castillo.

Poetry serves as a primary conduit for my narratives. In my personal practice, the use of words in poetry becomes more particular and meaningful, and the way words tie to each other, their place in the puzzle, becomes as important as the whole final structure of the writing.

As someone who writes poetry, this game of word selecting, pairing, embellishing—stripping down to the bone—is a process that I painfully enjoy. There’s nothing that can tell me when a line of writing is done more than the feeling that I can’t explain myself any better, and only then do I give up and cut my wins and losses. What is that for a process?

For me, addressing my art practice while being aware of the limitations it presents is at the top of my mind: as artists and designers, we want to be understood, but we are bound to find at least a certain degree of miscommunication.

My practice is mostly based on exploring all those communication hiccups that may occur on a text-based piece. These hiccups, or “frustrations,” as I like to call them, are the obstacles I try to highlight and, maybe sometimes, if I’m lucky, surpass by any possible degree.

By rethinking and deconstructing the idea of what a letter is, what a book is, they become pliable media for me to imbue with additional context and ideas. The reader then becomes an active researcher, a player. The tactile and interactive elements I add to my text-based work and books strive to expand the reader’s attention span, and further the connection with the concepts within each piece. As in the case with The Yes and No Book, having text mirrored and including the reflective paper to help read it better, I highlight the effort of reading the reflected words as more of a commitment from the reader, a reflection of the decoding of meaning in itself.

For my artwork Under The Rocks, I aimed to let go of the idea of a typical book altogether: that is, words printed on paper, bound in a particular order to offer a laid-out narrative.

I wrote a 15-line poem that I printed backwards on the bottom of cement figures resembling rocks. The figures were placed on top of reflective mylar, and in order to reflect the words written on the bottom of the “rocks”, the reader has to physically pick up each one to do so. A casual viewer may never even notice that there’s something to read under the rocks at all.

This non-linear narrative may present different degrees of success or failure: does it really work as a visual poem if it’s not really apparent that we need to pick up every rock to be able to read the entirety of the writings? Do we miss something by not being able to read the texts in a specific order? If we don’t notice the words and miss out on reading the poem altogether, is that different from any other interaction with an art piece in which the meaning seems to elude us?

I came across an article by the philosopher Mike Borkent titled Visual Improvisation: Cognition, Materiality, and Postlinguistic Visual Poetry, in which he details elements of visual poetry, for which he says:

Visual poems disrupt common understandings of language through its materiality, how the creators engage in improvisations around these understandings to develop the unexpected, and how the poetic artifacts prompt dynamic inferences and improvised understandings in readers.1

The idea of improvised understandings caught my eye, given that it suggests a not-so-successful attempt at making sense, leaving to the reader the job of “filling the gaps,” kickstarting a process of creation or rebuilding of sense from the reader. Maybe we shouldn’t run away from those hiccups and frustrations so fast: perhaps allowing space for miscommunication can give rise to new meanings and unexplored paths.

Writing in a second language has been tricky for me. Sometimes I am not sure about which word best represents what I want to convey. This leads me to feel that I am not able to make myself fully understood and that the message that I deliver is faulty, incomplete.

I have even used the notion of improvised understanding in my artwork to highlight the difficulties of navigating in a second language, being unfamiliar with certain linguistic, social, and cultural codes.

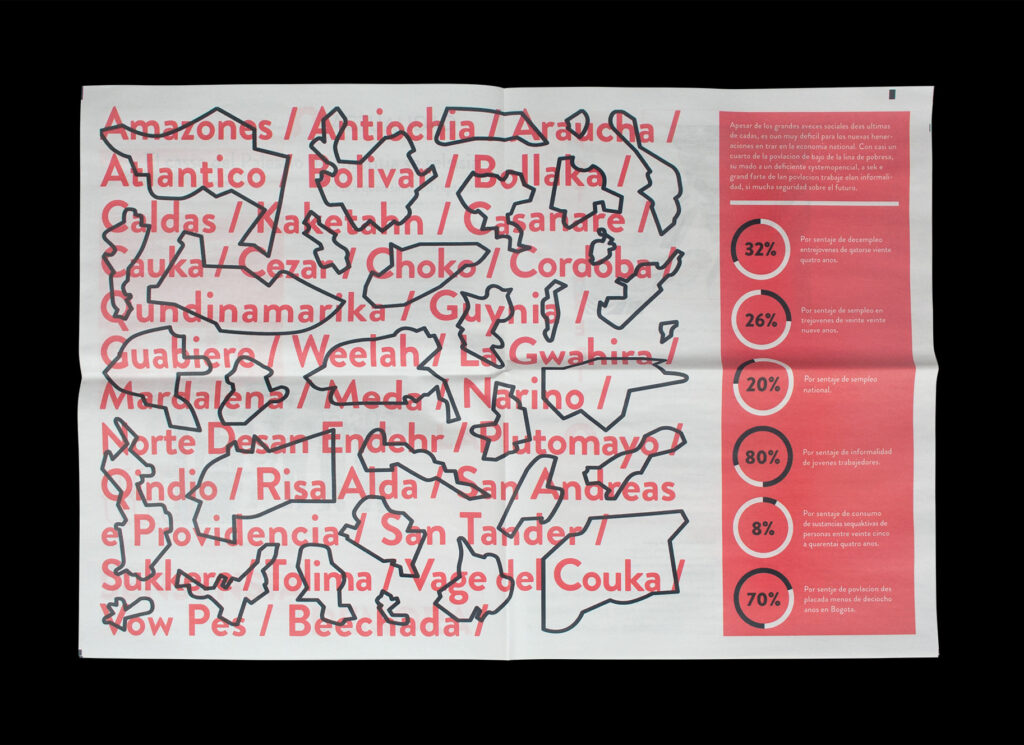

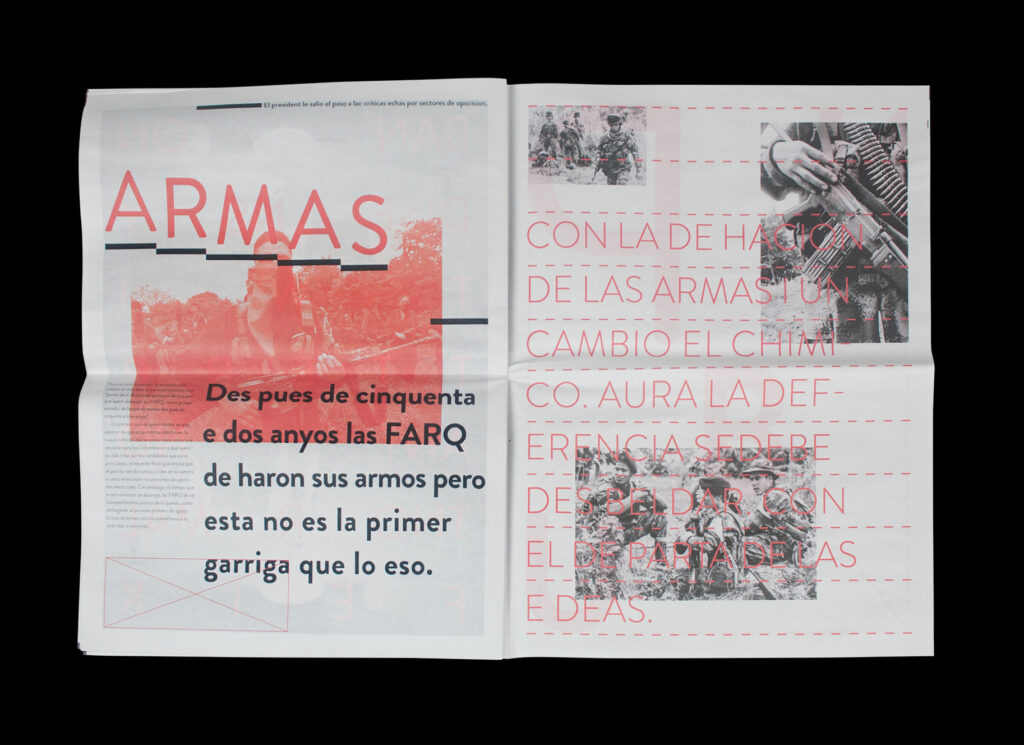

María José Castillo, The Lorem Ipsum, 2017. Photo: María José Castillo.

María José Castillo, The Lorem Ipsum, 2017. Photo: María José Castillo.

María José Castillo, The Lorem Ipsum, 2017. Photo: María José Castillo.

This project, titled The Lorem Ipsum, was presented in a traditional newspaper format, showcasing news from Colombia and the United States of America, specifically from the period the project was developed, summer of 2017. Using phonetic translation techniques, Colombian news in Spanish was orally dictated to people without any knowledge of the Spanish language, with the request that they write as they listened. Vice versa, English content was dictated to Spanish-speaking people without any knowledge of English, who registered what they could understand phonetically as they listened.

This exercise represented the hardship of understanding site-specific language from a foreign and unfamiliar perspective. When we listen to news originating from a distant place, we are incapable of grasping its entire meaning; we are removed from its native context, reducing our chances of empathizing and communicating effectively with other cultures. In my personal experience, these issues resemble the exercise of trying to read a text in a language that I don’t know: I might be able to recognize words formally, given that they may be using the same alphabet I am familiar with, but the words don’t convey any meaning to me.

There’s also the issue of what happens to a message when it goes through a process of translation. Colin Cherry, a cognitive scientist obsessed with the concepts of auditory attention and communication, presented some insightful thoughts:

A text, when translated from one language into another, may lose or change a great deal of its emotive force. When I read French I need to become a different person, with different thoughts; the language change bears with it a change of national character and temperament, a different history and literature. The translator of poetry really has an impossible task.2

In this analysis, Cherry alludes to a sense of identity inextricable with the language used by a cultural group. Within this scope, we may also look at the influence it has on our personal identity: after all, we develop memory through language and our memories constitute our history. It is worth considering how our use of language influences the way we store our knowledge and how we access it over time.

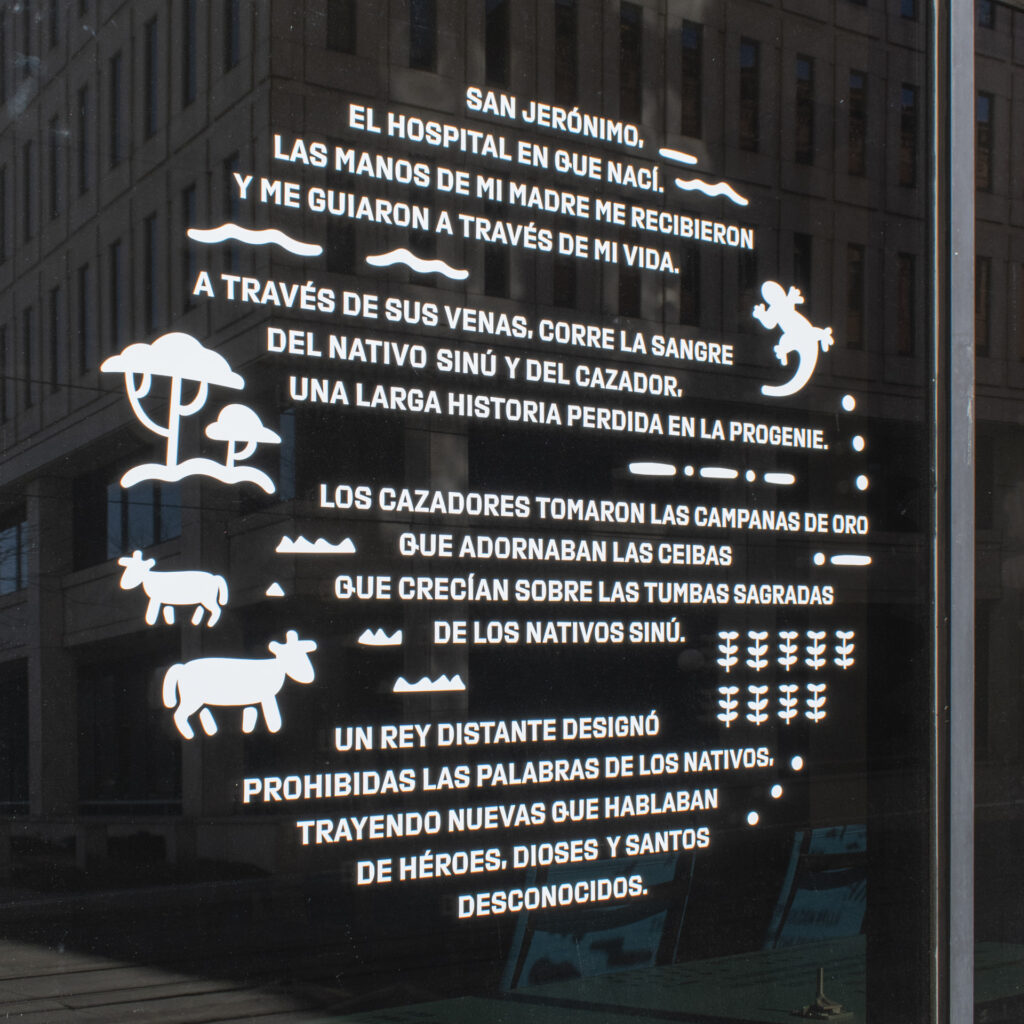

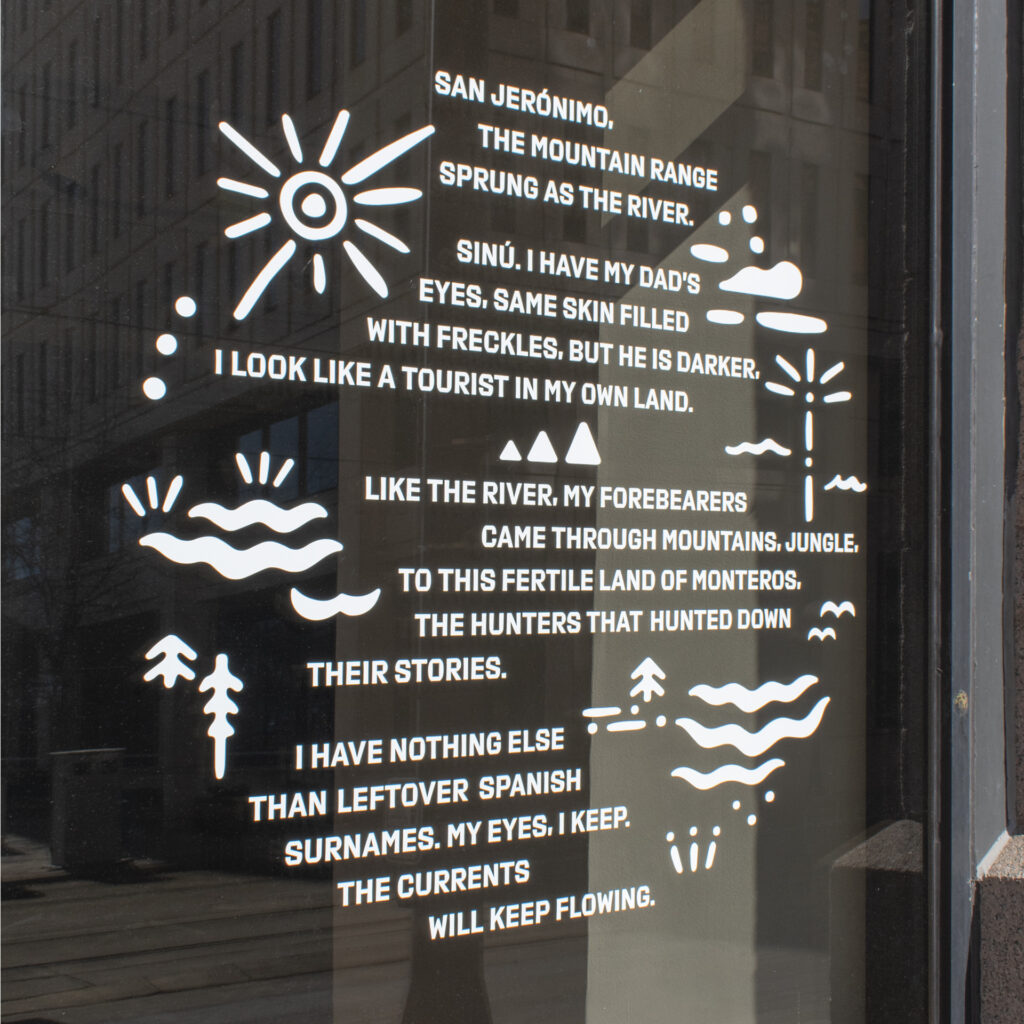

María José Castillo, El Río Sinú / The River Sinú, 2022. Photo: María José Castillo.

María José Castillo, El Río Sinú / The River Sinú, 2022. Photo: María José Castillo.

María José Castillo, El Río Sinú / The River Sinú, 2022. Photo: María José Castillo.

María José Castillo, El Río Sinú / The River Sinú, 2022. Photo: María José Castillo.

I put these notions around language and translation to the test while developing my visual poem and installation El Río Sinú / The River Sinú, a reflection on my cultural background as a mestizo with ethnic origins rooted in historical conflict. The piece was on view at the Minnesota Museum of American Art.

Through interviews with my family members, I collected information about my ancestors and contemporaries who have lived in the Sinú Valley, in the Caribbean region of Colombia. These conversations shed light on my ancestors’ relationship to the land—as farmers and cattle ranchers, mostly—and their genealogy.

Featuring my family’s history and migrational movements, the poem addresses the Spanish conquest, which altered the social and natural landscapes of Indigenous tribes. As part of this conquest, Indigenous stories, languages, and cultural heritage have experienced a process of erasure, a reality that continues today and makes it challenging to grasp the rich histories and legacies of Indigenous people through the Americas.

I decided to showcase the text in both Spanish and English, as a way of telling the story in my native language—in itself a byproduct of colonization.

The geographical repositionings that I have experienced in my lifetime have certainly influenced the way I see the world. Writing and other derived artistic practices I engage in are ways to make sense of my own history. I expect any reader of my work to draw on similar, big and small experiences around words, language, and communication that have influenced their own lives, and reflect on how they can make sense of them as well.

Dealing with subjects like site-specific language and translation from a personal perspective, analyzing communication challenges, and understanding how art and design can overcome these barriers remains at the forefront of my practice up to today.

I would like to conclude with some words from art critic and curator William Gustavo Franklin:

“What would Castillo do with three, four or more books? To craft nostalgia is not commercial construction. One is reminded of the creative and heroic impetus of Hannah Höch to make collage a stance against the ills of the world while advancing the evolution of the self. Precious risks await during the domination of materials, and words are a natural ally and contender in the archaeological thought process of the mind.”