Unsung Alchemist: Hollis MacDonald

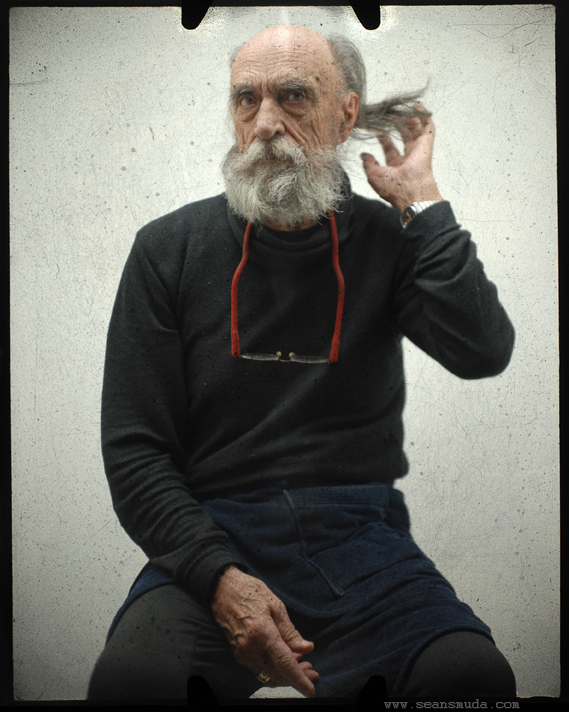

In the '60s Hollis MacDonald enjoyed the recognition of critics and gallerists alike. On the verge of hitting it big he disappeared mysteriously from view--until Sean Smuda ran into the reclusive artist living in the apartment downstairs from him.

Editor’s note: We’re re-running this profile, originally published in March 2009, because we’ve just learned of the artist’s passing.

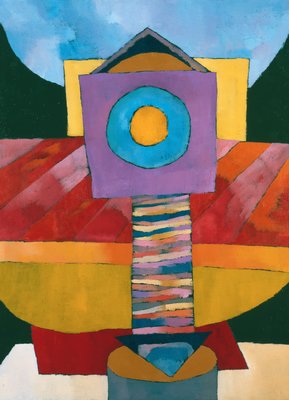

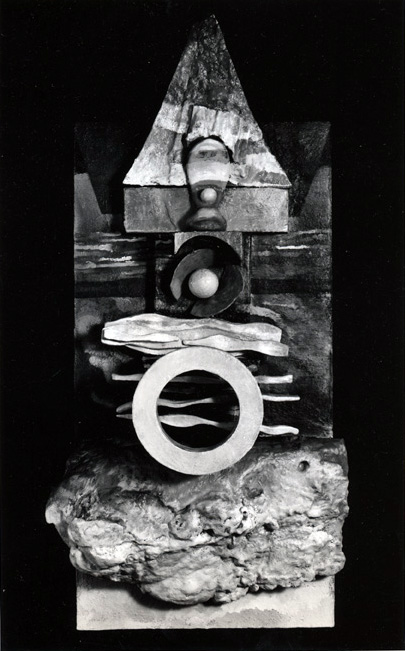

I GREW UP WITH THE PAINTINGS OF HOLLIS MACDONALD. Their soothing pastels and occasionally speckled, masonry-like surfaces contain sculptural and mysteriously theatrical landscapes. Some of his geometries evoke the grandeur of the Great Pyramid; others feel more like a heap of mute signs.

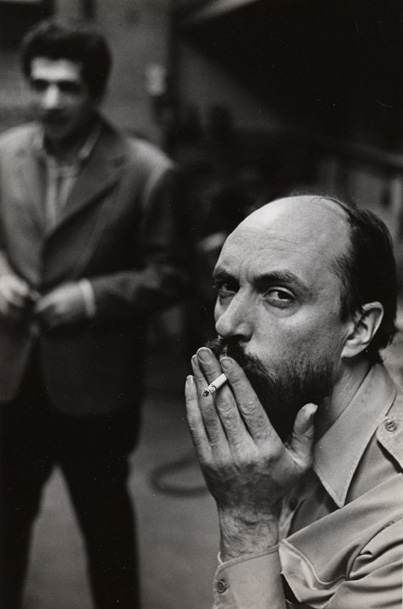

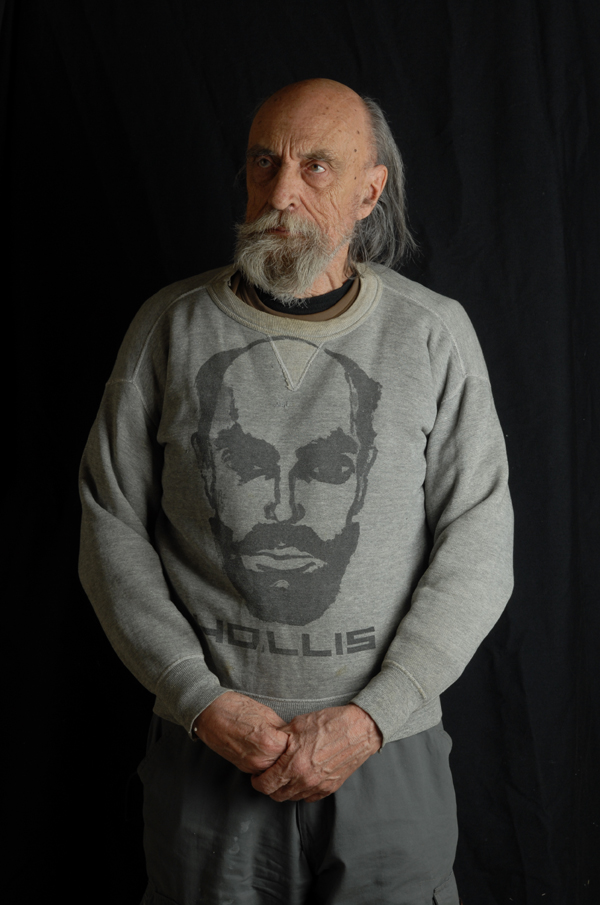

I also grew up wearing his stern, bearded, balding, and moustachioed visage on a grey silk-screened sweatshirt. Despite being surrounded by his artwork, information about Hollis, the man, was scant. My parents and their friends, when speaking about him, mostly recalled his exasperating qualities, his buffalo-like stubbornness. The mind behind the art, however, was an enigma–he was more myth than man. His remained an apocryphal story, a cautionary tale of the resiliency of the artist.

Then, a few years ago he moved into my building and, with him, came a chance to crack the cosmic egg.

For those who spend time in his company, Hollis drops cantankerous and poetic-philosophical kernels that bristle, but rarely resolve into epiphany — his are the raw materials of insight, not neatly packaged realization. A beautiful example: “Before there was alphabets — most people don’t realize how the world was before alphabets, before writing, because there was a longer period before writing than after, up to now — so we, we’re… what we got in our fucking heads is all wrong.”

And why should he worry about whether his listeners understand all he’s saying? Any 80-year-old (Hollis was born just before our last depression in 1928) has earned the right to offer up hard-fought wisdom on his or her own terms, without the niceties of explanation or apology. Hearing him hold forth, no matter how repetitiously or circuitously, makes me wonder about the nature of transcendence. What are the tensions and interplays connecting the raw to the refined? Listening to Hollis, it strikes me that neither can leave the other far behind — the unformed and the finished are inextricably linked and mutually sustaining.

The Way is Not Easy is exemplary of his search to transcend such duality and arrive at “ultimate essence” (as Alan Watts, one of Hollis’s favorite authors, would say). His use of a single up/down arrow simply and effectively conveys the predicament of the work’s title. The painting is a stage that is also a landscape with a birdhouse that is also a target that is also part of the arrow. Where to go and where to rest? These interchangeabilities, rendered in MacDonald’s pop-cubist style and marked by a curious asymmetry, are thought and spirit-provoking.

________________________________________________________

The very act of seeing Hollis’s paintings becomes a philosophical, if not moral endeavor, as the viewer works to identify the energies and orientations driving both the painting and himself.

________________________________________________________

Hollis says, “I paint non-objective because it develops …off-balance kind of shit.” This “off-balance shit” develops into a meditative game of space and color relations; the viewer’s eye becomes an actor organizing the painting’s puzzle of sign and pattern archetypes and their in-betweens. The very act of seeing becomes a philosophical, if not moral endeavor as the viewer works to identify the energies and orientations driving both the painting and himself.

In this, Hollis has something in common with both Paul Klee and Arthur Dove1. Like Dove, he aims to create a perfectly self-contained, otherly world — a cosmic egg. Like Klee, when Hollis talks about his work, he frequently returns to the topic of child-like wonder. As Hollis says, “any discussion of art should begin with the fairytale.” The Way is Not Easy, and the many more pieces like it, evoke this innocence and confrontation with the unknown.

Acclaim, opportunity, and experimentation marked Hollis’s artistic life in the ’60s. Hot wire foam and melted wax sculptures echoed the shapes found in his paintings. His flair for the transformational extended into the sensational. A clipping from the Minneapolis Tribune in 1966 shows him dramatically enacting French sculptor Nikki de St Phalle’s piece, which entailed shooting a pop gun into plaster paint balloons on canvas.

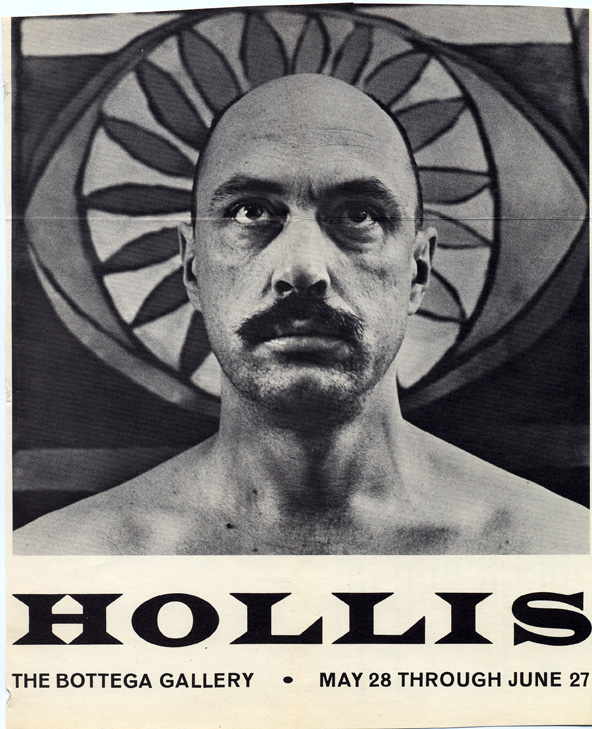

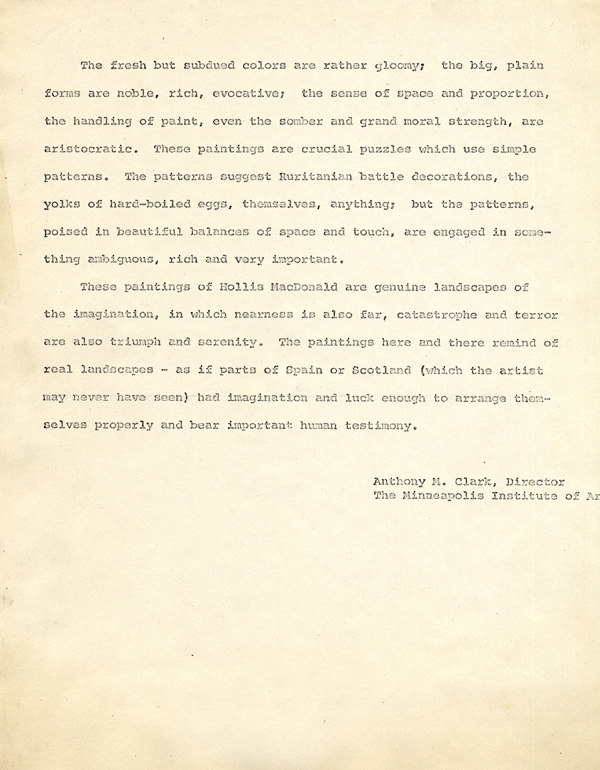

Solo shows, awards, and poetic endorsements from local critics such as John Sherman and former director of the MIA (1963-1973) Anthony Clark seemed to indicate Hollis was destined for a larger sphere of influence. Thus spurred on, Hollis and his wife Karen Meyers moved to NYC and into a studio on Broadway and Canal, close to Robert Rauschenberg’s (whom he’d met when they’d both shown at the Walker).

However, Hollis’s promising career foundered as his personal life unravelled. The dissolution of his marriage, in particular, seems to have occluded his eye-in-the-clouds career. Without the support of his wife, the artist became increasingly monastic. His inner revelations were committed solely to canvas; Hollis was no longer interfacing with society via exhibitions or performance. While brother artists such as Jerry Rudquist and Mike Lynch soldiered on in spite of their personal tumults, MacDonald became more insular–his redoubtable beard thickened and his pronouncements became more absolute, more buffalo.

Hollis’s pronouncements are practically insoluble, a veritable Zen apocalypse of opposites and paradox; but, like his inference about the alphabet’s pernicious effects, his insights are pregnant with meaning, too. In spite of his opacities (or because of them), his oblique utterances fulfil his own definition of genius, a concept he says has its origins in the Latin word meaning “God and the Devil”2.

________________________________________________________

In the wake of personal tumult, MacDonald became more insular –his redoubtable beard thickened and his pronouncements became more absolute, more buffalo.

________________________________________________________

Hollis — his artwork, his career — is not at the crossroads of genius and failure, he is the crossroads. Any apologies he makes for himself, which he does with contradictory frequency, sound like obfuscations, the sort of disappearing-act typically employed by scholars and mystics hoping to obscure their philosophical vulnerabilities.

He’s a man with a penchant for regrets, swearing, and juxtapositions of current events with half-explained epistemologies. And yet, his art pulls him in the opposite direction, one where his prickly questions are neatly resolved with a deus ex-machina expression of transcendence.

It is surprising that he didn’t hit it bigger in the ’60s, given his flair for self-promotion. As a prescient pre-Warholian totem, his aforementioned T-shirt made an impression, and not just on me. He recalls, “Henny Youngman bought one to wear on Carson, but then he got cut. Luck of the Scot!”

Despite his bluster, Hollis’s brutal honesty is refreshing, intriguing and often full of heart. He speaks with rough affection, as though imparting wisdom to a child. He’s become the gruff mystic who has no need of society, but has a lot to say about it.

And of course he is reading a book about (artistic) alchemy that he highly recommends: Fire in the Crucible3. It explores ‘”omnivalence”: a sense that beyond the tensions of uncertainty of this life there is something more, something that makes an aesthetic act “an imminence of a revelation which is never fulfilled”4. This revelation need not be fulfilled; it is in his hermetic act of creating wondrous worlds that MacDonald succeeds, whether he shows them to us or not.

As is typical in our conversations, Hollis demurs as he talks about the book on alchemy, “If I had only read it ten years ago.”

In the end, Hollis need not worry. His artistic path has been assured, if zigzagging. Despite persistent frustrations and inactivity due to the recent loss of yet another studio, the artist himself is much as he ever has been: a brilliant colorist and juggler of mystic and emotional forces, working in exile on imaginary landscapes. As he says in a 1965 interview, “I try to make a painting that lives…. It’s kind of like making love, you can’t tell when you’re giving and when you’re taking.”

______________________________________________________

About the author: Sean Smuda lives upstairs from Hollis.

______________________________________________________

1 Dove once wrote “I would like to make something that is real in itself, that does not remind anyone of any other thing, and that does not have to be explained like the letter A, for instance.”

2The word, “devil” comes from “deus” (Latin) or “diva” (Sanskrit) meaning God. When you speak of the Devil you speak of God. –Albert Weibord, from the magazine La Parola del Popolo June/July 1961