A Dispatch from Publishing’s Digital Underground

Author of two mid-list books, David Oppegaard set out to publish his sellout novel, a foray into the hugely popular YA fantasy genre. Caught between traditional and e-book publishing, he offers a field guide to the shifting sands of the books business.

MY THIRD BOOK WAS SUPPOSED TO BE MY SELLOUT NOVEL. Oh man, it was going to be great: a dark YA fantasy about a young girl who’d been kidnapped and the three plucky youngsters who venture out across a dangerous world to rescue her. My two previous novels (The Suicide Collectors and Wormwood, Nevada), both published by the well-established St. Martin’s Press, had been a little too multi-genre for the traditional publishing model and their sales had suffered for it, despite mostly great reviews and a Bram Stoker nomination. So, in the interest of actually making some cash and helping out my hardworking literary agent, I was going to craft one hot-selling gem of a novel aimed directly at the vibrant young adult fantasy market.

I rolled up my sleeves and started writing. Happily, I found myself gradually sucked into the novel more than I’d anticipated. The magical world grew, as did the characters, and I started to dream about them at night, something that had rarely happened to me before. I’d gotten big time lucky—I was falling in love with my sellout novel. I was living the working-writer dream!

When the novel (now titled The Ragged Mountains) was finally polished and ready, my agent sent it off to publishers while I sat back and dreamt of the great luxuries to come: I’d buy new tires for my car! About six weeks later, we had a nibble from a major publisher (of course we did, it was a sellout novel) — more than a nibble, actually, it was more like a CHOMP. Suddenly, I was talking with an executive editor on the phone, feeling all jittery and excited while she spoke about how much she was looking forward to working with me on the book.

Then, the next day, it all fell through. The executive editor brought the novel up in a marketing meeting, and they couldn’t decide what age group it should be targeted toward (say, 13- and 14-year-olds or 15- and 16-year-olds?). And that question was enough, apparently, to ax the whole deal. I received a nice, apologetic email from the editor through my agent, and that was it. The gravy boat had sailed on.

And it kept on sailing.

______________________________________________________

In a publishing industry that feels itself to be under siege, anything outside the bounds of an immediately discernible, narrowly targeted readership isn’t worth the risk of investment publication entails.

______________________________________________________

Over two years passed, and The Ragged Mountains never found a home in traditional publishing. It wasn’t the first time this had happened to me as an author (as I write this, my long-suffering agent has, to date, represented five Oppegaard novels that have not yet found a publisher and probably never will). But this was the first time I’d set out to create a highly marketable novel and found my work turned away at the last moment, due to what seemed to me a profound lack of courage on the part of the publishing establishment. The reluctance to pick up my book was never expressed as concern about the quality of either the story or the writing in The Ragged Mountains; it was a good book—my agent and I knew it was a good book. The quibbles were about whether the book fit the perceived market perfectly. In a publishing industry that has been under siege for fifteen years or more (or, at least, felt itself to be under siege, which might be even more important), anything outside the bounds of an immediately discernible, narrowly targeted readership isn’t worth the risk of investment publication entails.

So, I chalked this near-sale experience up to bad luck and went back to writing, keeping my head down as I moved from project to project lest I lose courage and stop working altogether. I didn’t consider e-publishing, at first, because I am an old-school type; I clung to the belief that the traditional, print publishing model was still viable (despite mounting evidence otherwise). I thought, surely brick-and-mortar publishers exist for a good reason: If anyone could publish anything they felt like, any time they wanted to, then what have I worked toward all these years? Dismiss the role of the publishing house, and I’d be left to question whether my lifelong dream of becoming a “published” author was ultimately meaningless. And if that major part of my identity as a writer proved fruitless, what did that make the rest of me?

In an effort to dig a little deeper into the current-day publishing muddle, I recently emailed several local publishing luminaries, asking each the same three questions. They gave me many compelling responses to those questions, from which I’ve cherry-picked for the sake of brevity here, but have posted in their entirety on my blog:

1) Do you see electronic books and print books ultimately cohabiting peacefully together in the marketplace, each with their particular consumer base? If so, how do you see the market’s share of readers being sliced up in, say, ten years from now?

Ten years from now is a pretty big shot in the dark, as things seem to be changing fairly dramatically every two to three years. My guess is that e-books, or some variation on them we haven’t even fathomed as of yet, will share a piece of the marketplace. But the surge in e-books over the past couple years isn’t sustainable over the next ten years–it has to flatten out a bit.

–Hans Weyandt, owner of Micawber’s Books

I don’t see printed books going away altogether, at least in my lifetime. I think that as long as there are children who are exposed to books on paper at an early age, there will be some level of attachment or affinity for that form. Right now, to me, the printed book is still a superior technology. We’ve had a lot more time to work out the kinks with it. I am confident that

e-books and the industry, in general, will continue to evolve, but right now it’s difficult even to speculate about market shares ten years down the road.

–Katie Dublinski, associate publisher at Graywolf Press

I believe it will depend very much on the genre. I imagine, for most things, including literary fiction and serious nonfiction, there will be peaceful cohabitation, but for others genres I think we’ll see print disappear entirely, with the exception of a few major titles. This is all guessing, but I suspect we’ll see 40% e-book share in 10 years for the former.

-–Jonathan Lyons, Lyons Literary LLC

2) A physical book already seems like a perfect technology to me. Why do you think so many readers have embraced reading long novels on electronic platforms when their days (and nights) are already dominated by electronic devices such as iPads, laptops, cell phones, etc.?

To me, the convenience of e-readers begins and nearly ends with purchase: It’s so easy to buy books this way. Reading them, I find, is not so simple. I wrote a blog post about this not too long ago, which drew a lot of comments from sensible-sounding people who took me to task for being a stubborn Luddite. They had a lot of reasons for liking their e-readers: they liked the ability to blow up the type size, to carry an entire library with them in one slim device, and to feel “green” because they’re not using paper. I also know people who prefer e-readers for their “guilty pleasure” reading—light stuff that they will never want to read again and don’t want to keep. They download the book, read it, and then delete it. They’re not mucking up their house with stacks of paperbacks they’ll never look at again.

-–Laurie Hertzel, Book Editor at Minneapolis Star-Tribune

I read a lot on my iPad, Dave. I carry it everywhere I go. I have books for school on it. Books I want to read, but haven’t yet, but hope to find time to get into. The book I am reading currently [I’m reading on my iPad]; favorite books I want to quote from in class. Three of my own books I use when I do readings at middle schools and high schools. I’d have to hire a donkey to carry all that with me. Also, it is back-lit so Steph, my wife, can sleep easily while I read. I love the feel of a book in my hands, but I love my iPad, too. I read more because I have it. Also, if I’m inspired to read a book I don’t have, I can get it in a matter of minutes. I know, despicable, but I love it.

–-Geoff Herbach, author of the YA series Stupid Fast, Nothing Special, and I’m With Stupid

3) How much power do you think marketing departments in traditional mainstream publishing houses have over what books (and the authors behind them) rise and fall in the marketplace? A jaded mid-list author might feel that even fiction books are now being set up, either to succeed or fail, from the moment their initial print run is decided, especially in the bigger publishing houses.

Are you kidding? They have an enormous amount of power. Like anything, or almost anything, [publishing is] very old-fashioned and all about power brokers and relationships. It’s not a very big world and so money talks, as usual, and so do “old ways of thinking” and who-went-to-college-with-who. However, sometimes, luckily, other stuff breaks through. Look at the tremendous amount of press George Saunders got this past month. He’s a great writer, sure, but that wasn’t about merit, it was about flexing power in the industry to make something happen.

–-Chris Fischbach, Publisher at Coffee House Press

I do believe the marketing departments play a huge role, in that they may focus more on some titles than others. We’ve all seen this internally in publishing. Yes, it can affect the rise and fall in the marketplace. Yet, there are steps any author can take to also keep a buzz around his/her book. Social media is extremely accessible, and once a person meets the right people in the social media – good things can happen as those relationships develop. In the pre-internet days, one had to depend on the marketing departments to help in the promotion of a book. Now, there are multiple outlets and ways to reach out to readers and fellow writers. My theory is that it’s in the best interest of any author to come up with a detailed marketing strategy and execute it, along with the publisher’s plan. Additionally, authors need to be prepared to promote that book for at least three to five years [after publication].

–Dawn Fredrick, Red Sofa Literary

______________________________________________________

It seems like modern readers are punishing books simply for existing in meat space at all — as if our lives are so cluttered by physical books that those volumes must either be crammed beneath a flat screen or risk being ignored outright.

______________________________________________________

Luckily, backed by an agent who still believed in my work, I moved on from the disappointment and wrote new books. Yet, the idea of publishing The Ragged Mountains wouldn’t leave me alone. It was a good book and deserved an audience. Leaving it on the shelf out of stubborn, old publishing-model pride was like having a great kid and locking him up in the basement. So finally, after gritting my teeth and poking around, I decided to publish it myself as an electronic book.

The first step toward publishing an e-book in a professional manner is to have a clean, well-edited manuscript you can be proud of once it’s released into the world. Normally, unpublished writers would be well-advised to hire (or kidnap) a freelance editor to polish their writing (which can cost anywhere from $1000-$3000, easy). But I had the rare advantage of a sharp-eyed literary agent who’d already combed the book over several times; given that, I felt my manuscript was clean enough for public consumption.

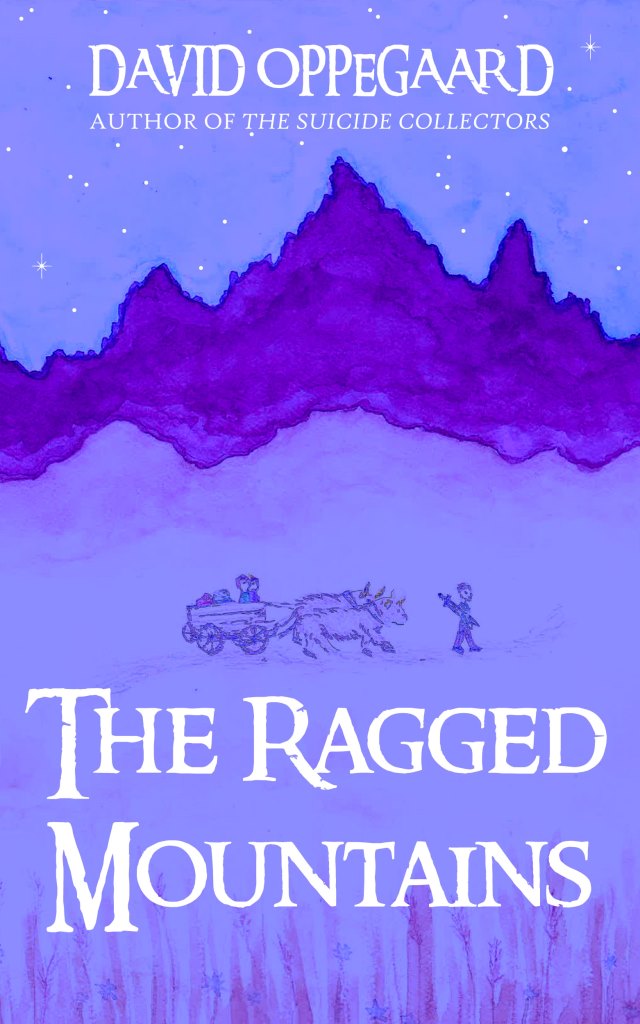

The next major step to e-book publication is coming up with a polished cover design that draws the eye and screams “kickass professional” and not “broke-ass amateur who doesn’t really give a damn.” People do judge books by their covers — especially online, where self-published books by unknown authors have little else to recommend them to readers. An author can pay a freelance graphic design artist to come up with a cover (again, not a cheap proposition), or go the grassroots, commission-your-friends route.

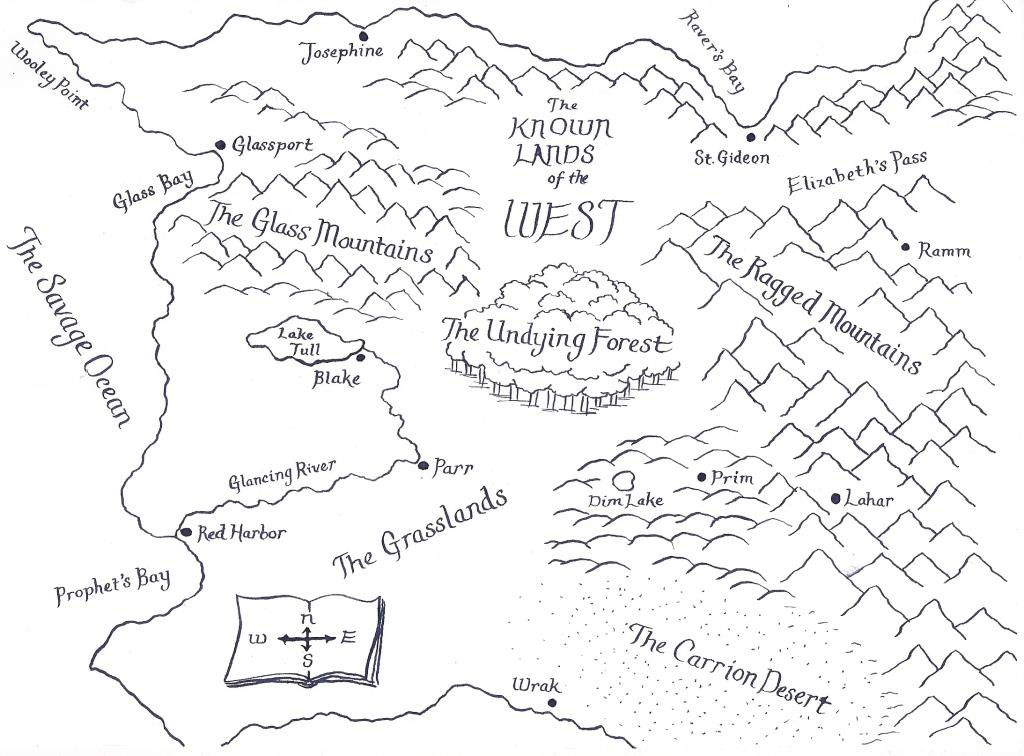

Happily, I am friends with an artist, one Sarah Morse, who had read and loved the book, and whose artwork shares the novel’s classic fantasy sensibility. She took a stick figure-level drawing I’d made on a coffee shop napkin and created a watercolor-and-pencil illustration that captured exactly what I’d imagined. From there, I delivered the cover art to my cousin, Steve Norman, who handled the graphic design details: converting the original art to a digital image, adding the title and author name in a cool, epic font, and, literally, converting the image from day to night.

Thus, armed with both a professionally polished manuscript and cover, I was faced with actually publishing the thing somewhere. Currently, Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP) dominates the online self-publishing industry, backed as it is by the Amazon.com monster and featuring the Kindle reading device (in its several manifestations, including the popular, new Kindle Fire); but there are alternate self-publishing sites, such as Smashwords, which is a free site that allows authors to publish an e-book once, and then send it around to numerous other e-book stores, including B&N, Apple iBooks, Sony, Kobo, and others (though not Amazon, which demands you publish through them and them alone).

After consulting my agent (which felt pretty weird, honestly, since he was now effectively cut out of the publishing process), I decided to release the book initially through Amazon and join their Amazon Prime publishing program, which requires authors to release the electronic format of their books exclusively through them for 90 days. In return for this electronic exclusivity, you’re given five promotional days in which you can choose to give away your book for free (yay?); this scheme also enters your book in the “Kindle Lending Library,” which means Kindle readers can “borrow” your book, for free, for a certain period, thus giving your work greater reach (theoretically, at least). I figured that once the 90 days were up, I could release it across every other e-book platform via Smashwords.

So, finally, The Ragged Mountains had found a digital home. And I am proud of it — proud of the loving work my friends have done on the book’s behalf and eager for the story to find its audience. Unfortunately, finding a readership is the great and mysterious riddle of self-publishing success, the murky devil hiding behind the details. Yes, once again, I’m finding that writing a good book has collided head-on with the marketing machine (which has now become both the main attraction of going with a traditional publisher and its fearsome gatekeeper).

I created a Facebook page for The Ragged Mountains, posted a release note for it on scribd, announced it on my blog and my author page, tweeted it, added it to Goodreads, announced it on my podcast, tweeted it through my podcast’s Twitter account, put up a sweet book trailer for it on YouTube, updated my Amazon Author profile, and blasted an email with a friendly release note to basically everyone I knew throughout space and time. I also submitted it for review to the handful of respectable online publications and reviewers willing to review self-published e-books So far, The Ragged Mountains has only been considered by reviewers who fondly remember my traditionally published work. I can only imagine garnering reviews is even more difficult for first-time authors.

***

What has come from all this sound and fury? Well, as I type this — two months into the book’s digital release — 15 copies of The Ragged Mountains have been purchased online.

That’s right: My carefully aimed sellout book has garnered 15 sales (and zero “borrows”). And, let me remind you, I’m an author whose critically acclaimed first novel The Suicide Collectors was published only a few years ago: released in hardcover, trade paperback, book-on-tape, and as an e-book, before being translated and re-released in Italian and Spanish. Hell, I have over 300 friends on Facebook alone!

Of course, selling copies has not been the point of releasing The Ragged Mountains. It’s been about giving a good book a chance in a crowded, noisy world where even my friends don’t always have the time or the willingness to watch a four-minute book trailer, much less read my new book-length work. The Ragged Mountains is floating on the vast electronic sea, ready and available for anybody who chooses to spend time in its unique world. And since I’ve got a steady day job and no longer harbor any illusions of supporting myself on book sales alone, that’s enough for me.

Still — I occasionally look at my bookshelf and long to see the physical manifestation of so much work and love. I still wish I could hold this third novel in my hands and smell its fresh, ragged paper. It feels sometimes like modern readers are punishing books simply for existing in meat space at all — as if our lives are so cluttered by physical books that those volumes must either be crammed beneath a flat screen or risk being ignored outright. In Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury portrayed a world where books were illegal, and firemen were responsible for burning all existent copies. Today you could probably destroy a healthy amount of fiction with one well-placed electromagnetic pulse. In any format, it seems the struggle continues for books, as they try to find enough time and space in the lives of their readers, while other forms of media flourish madly, everything just a click away.

______________________________________________________

About the Author: David Oppegaard is a novelist living in St. Paul. He is the author of the Bram Stoker nominated The Suicide Collectors, Wormwood, Nevada and The Ragged Mountains. He teaches the occasional fiction class at Hamline University and the Loft Literary Center. He also co-hosts a comedic film review podcast called When Harry Met Fatty. Feel free to visit his website at davidoppegaard.com