Exchange: A Conversation on Painting with Bruce Tapola

In this informal, artist-to-artist interview on studio practice, originally published in 2010, Ruben Nusz and Bruce Tapola chat about painting - the uncertain terrain of critical value and success, material inspirations and the benefits of "slow looking."

introductionThis occasional series of artist-to-artist conversations — led by artist, and painter, Ruben Nusz — aims to probe at the heart of the daily practice of working in the medium and, perhaps, in so doing to reveal something of the deeper significance of the process, simple human effort, and intention involved with making art.

For this first interview in the series, Nusz talked with St. Paul artist and St. Cloud State professor, Bruce Tapola, who has shown work at Franklin Art Works, Midway Contemporary Art, Art of This and the Rochester Art Center.

Ruben nuszEven though much of your new work is sculptural, I’d like first to talk about painting and, specifically, about slowing down. Painting isn’t a quick process, and the work unfolds over time – do you think this sort of practice, this slowing down, has something to do with what keeps painting relevant?

Bruce TapolaI think you can slow down any art form, make it with less spectacle. I think we get out of the habit of thinking that slow looking, too, is valuable (which it is). Maybe we lose the patience for it, consciously, even subconsciously.

RnWhat do you mean by “slow looking”?

BTIt gives you an opportunity to allow whatever thoughts you’re having to branch out into the unfamiliar, to make connections that are important, but which might slide under the radar; what you notice might not even be namable. Slow looking gives you space to think — the same reason most people like weekends at the lake, or in the woods.

RnWhat separates going to the lake and making art? Is one activity more valid, more worthwhile?

BTI wouldn’t say one is more valid than the other. Vacationing and art-making sometimes coincide — those mental states, anyway — and when they do it’s wonderful! I was listening to NPR and this guy was talking about our choices, and about our reactions to the things that happen to us as a result. For example, if I asked you, “Ruben, what if you won the McKnight Grant? How would you feel? Or, if you lost it, how would you feel?” I suspect our predictions about our responses are way off. In the instance I just mentioned, you’d probably never remember either of these events as the best or worst days of your life – but when you apply for something like that, the outcome seems so important. It comes back to managing expectations.

RnWhat are your expectations? What should we expect from art? Does art, or the making of it, entitle us to anything?

BTNo, I don’t think we’re owed anything. Maybe it’s very romantic, but I think we as individual artists owe something to the idea of art, if we’re going to call ourselves ‘artists’; we owe our sincere intention. I hate to be the guy who scolds people, and I wouldn’t presume to determine anyone’s ‘true intentions’, but we all have opinions about some of the work we see, work that doesn’t seem genuine. I think, from time to time, we’re all fairly sure that certain things we see just stink.

RnBut, sometimes, I think there’s a falseness to my certainty about the merits of what I see. I wonder if I’m just shielding my own ego, if I should remove “this is good and this is bad” from the language in my thinking about art …

BTThat’s totally it! What if you allowed yourself the outrageous freedom not to commit? I mean, is ‘certainty’ a distraction, or is that getting you closer to the idea of art? I would argue that people need to be aware of things, you don’t want to be a moron, but in the pursuit of your art, if you’re not looking at these art magazines, comparing your work with what you’re seeing there, maybe the self is emancipated …

RnHow do you get in touch with your ‘true self’? I’m kind of a determinist by nature, but I wonder how it’s possible to really tap into an unfiltered, primordial self?

BTI don’t know who said this first, but “I conquered weakness by giving into it.” Sometimes artists, when they’re describing their work, start talking about shit that I’m not interested in, didacticism, and for me it starts to ruin this thing that they’ve created. I’m already into it! You had me with the image!

RnI think a lot of artists fall into that trap.

BTWe all went to art school!

RnYes, the reason we make visual art is so that we don’t have to have this conversation about the work. We can have a kind of synchronicity, between the idea and the image — even between the artist and the viewer — without the distraction of words.

BTI’ve heard friendly jokes about the way that I speak, and I’m not the most articulate. Sometimes I get fired up …

RnSo, how does one go about distancing oneself from these seemingly artificial, verbal definitions of art when talking about their work?

BTThis might sound really dumb, but I think you could just stop participating in those conversations. If you don’t like something at the grocery store, or if you oppose a company that makes a product, you don’t buy it. When I was in undergrad, in the early ’80s, it was uncool to talk about your career — this was the mark of a fake artist. The world, of course, has changed. The business world and the art world have become the same; the art world has adopted a more corporate model. Come on! We’re the artists, motherfuckers! So much of my energy goes into how to brand the work and… In my fantasy, I imagine conversations between artists of today with those from sixty years ago, when nobody had careers, so they had to talk about the work. It’s like, now we introduce ourselves through our resumes.

RnYou’ve got a great local resume — you’ve been painting for a while now. Do you think there’s more nuance evident in the work of older artists, the sort of sensibility you can only accumulate after a lifetime of painting or art-making?

BTI think their work has more nuance, but I don’t know. Maybe that’s why people don’t like me — I believe shit like that. That’s actually why I don’t care for stuff that’s too didactic or topical. If I want to know something about the war, for example, I probably wouldn’t go to an artist.

RnWhere do you draw inspiration for your daily practice?

BTMaterials, lately… Where does it come from for you?

RnThe library, for me…

BTHow do you determine if something is worthy of your pursuit?

RnMy goal in looking at and making art has to do with being moved — I want to be moved, directly affected, somehow. In my own work, the question is ‘how, then, can I make an experience to move myself?’

BTIf you’re able to do that, the rest will follow.

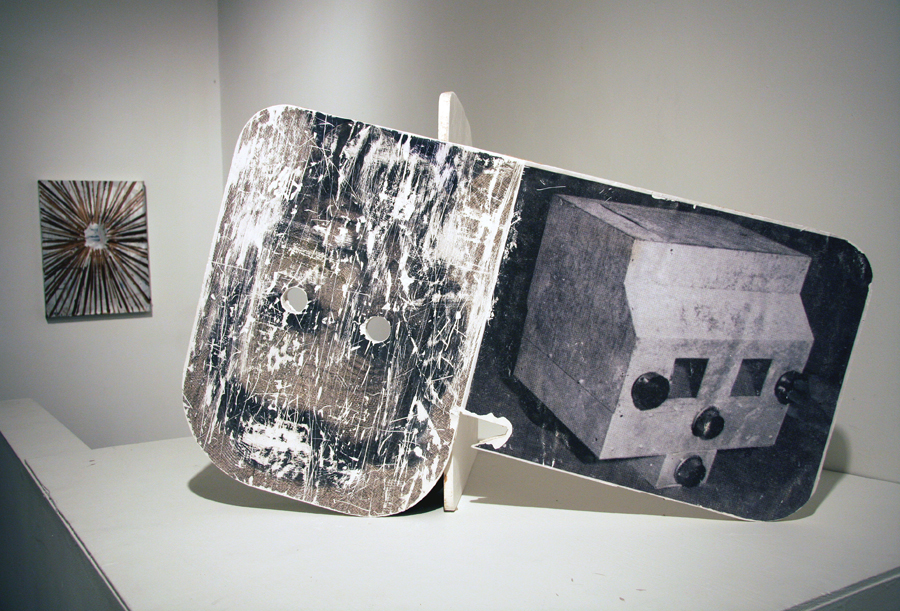

RnYou mentioned drawing inspiration from materials; there’s always a sensitivity to materials in your work. For example, plaster was prevalent in your Art of This show — what moved you to use plaster? You’re melding painting and sculpture, too. Are these medium categories meaningful, or are they just arbitrary?

BTIt seems natural for me to work with multiple media. There’s an acceptance of that practice now — you don’t have to define and commit to these categories. As the artist, you get to choose, and I’m open to everything. The biggest part of it, for me, is being sensitive to how these objects relate to the world and each other.

Painting, because it’s so boring and passé and conventional, actually gives an artist a lot of freedom. When you paint, you don’t have to think about newness; you can think about goodness.

rnJohn Baldessari teaches that one learns the trade to suit the idea, rather than vice versa. Is there something lost when art schools don’t teach and less motivated students don’t learn how to work competently with various media?

btSometimes, you visit a school and you look at the work of beginning painting classes, and most of the work looks rather tortured and bad. But then you look at an entry level multimedia class, where the kids are using Photoshop and everyone, really early in the game, looks like a pro. But in the painting classes, it’s just not going to happen like that. It’s like you’re carrying this giant bag of candy, and the kids want candy, but you won’t let them have any candy, and then all day long all you hear about is fucking candy. Beginning students all want to paint something realistic — and if you show them how to do it right away, then they understand a mode. But once it’s done, a real-looking basket and an apple, it becomes less amazing. Creating illusion of volume in your painting, on the other hand, is a potent trick; if you show them how to do that, they have a tool they can use in any number of ways – after that, they are on board, and you can show them other stuff. My projects are weirdo stuff — they’re different, like, let’s paint the worst, ugliest painting in the world.

rnDo you find when your students are working on that big project, when they’re making every decision wrong, that they’re actually making their best paintings of the semester?

btThose are the great ones! It might be ugly, but it’s potent! At the same time, it’s like this: I don’t play any music; even if someone brings a saxophone in here and I play it, that doesn’t make me Ornette Coleman.

rnHow do you react to the designation ‘conceptual artist’?

btThere’s a perception out in the world that ‘conceptual art’ is dry, remote even; but then there are some nice things, like the work in the Quick and the Dead

rnBut didn’t you find that show, at times, formulaic? One does this and then you do that and, voila, you have conceptual art!

btIt’s complicated. In the past, these sorts of gestures had no value; and then we placed value on them. Take the Robert Barry electromagnetic piece — this object didn’t limit anything. In its day, to the hipsters, it fit; but it probably wasn’t as comfy, even then, as it is now. I think it captures the big questions humans have, and conveys them elegantly, at a human scale.

rnThat’s how I feel about your work! One of the things I’ve thought about lately, with regard to painting in particular, is that – unlike, say, rock music – it seems like the perfect practice to grow into…

btI haven’t been painting as much in the last year — been making more sculpture. But painting, because it’s so boring and passé and conventional (like painting animal hairs on a stick), actually gives an artist a lot of freedom. When you paint, you don’t have to think about newness; you can think about goodness.

rnBy its nature, a painting isn’t new or avant garde — and maybe that takes the pressure off.

btAs a painter, you’re not going to be a rock star. Your goal could just be “I want to make something really good before I die.” You could be some older painter who’s “discovered” late in a life, like that woman from the New York Times. I’ve noticed this sort of thing twice in the last year: some museum director will say, when they’ve discovered an old lady like the one in the Times article, “How did she sneak under our radar?” What arrogance! Like their radar is so all-encompassing!

rnBefore we finish, I’ll ask you this, inspired by an interesting, similar question raised by arts writer Peter Schjeldahl: “So you’ve made a great painting — does it matter?”

BtSo, make it a personal achievement —

rnHere’s what I’m getting at: I was reading Artforum the other day – an issue from around 1962 — and, as I flipped through it, I kept wondering, “Who are all these people?!”

BtAnd with some of the most important art of the day, even if you remember their names, you might be embarrassed to mention them in front of company.

rnRight! And what’s worse is that most likely, after the same period of time, we as artists won’t even be “Artforum 1962″ forgettable; we will be Skyway News forgettable (no offense to the Skyway News).

BtFor real, though! I get the feeling that, after a while, the goal of some artists is just to see their name in the City Pages again. I would rather never show at all and, instead, have more ambition for the work itself. To really make good work would be better to me than making sales or gallery BS or getting press mentions.

rnDo you have more confidence in your work when artists you respect respond positively to it?

BtThat’s it. That’s everything. It’s important. But also…Here’s another example from something I listened to on NPR a long time ago: There were, maybe, six people, all from different walks of life. Somehow or other, each of these individuals had reached a pinnacle in their fields — one was an engineer, another was a well known writer, a business man, a dancer, etc. Each of them was revered in their fields, and an interviewer asked them all in separate interviews what kinds of decisions and plans they’d made – basically, how they ended up so successful. Every single one of them said they followed their nose, that they looked to things that interested them, and that they didn’t ask questions about “viability”. They never closed the door behind them; they stayed open to the possibilities that came, and then ended up in these amazing places. One woman had flown for NASA; she was a research scientist. She said, “Let’s say I had a theory about gnat wings. I could study them exclusively for ten years, every day in the lab, take them apart, thinking, ‘I have an idea about what all this will show me at the end of it.’ And there will be a point in that ten years where it’ll either show me what I expect to see, or it’ll tell me, ‘nope, it’s not gnat wings.'” She said she got no percentage in staying one second longer with her first expectations, because the goal wasn’t about being right, or making some specific achievement. She said her aim was just to engage with her activity in an honest way. I think making art is like that. You have to, at any juncture, be willing to throw it all away, to start over. With every piece, in the goofing around, there is something in there that has the potential to make a great artwork. But can you let yourself see it clearly? What it comes down to is this: the thing that means the most to me is me just making stuff in my studio. That’s what really matters.

This interview was originally published in February 2010.

About the artist: Bruce Tapola received his bachelor’s degree from the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, and his Master of Fine Art degree from Montana State University in Bozeman. His work has been featured in exhibitions at the Milwaukee Institute of Art, CSPS, Cedar Rapids, IA, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Midway Contemporary Art, Locust Projects, Miami, Franklin Artworks, the Rochester Art Center, Art of This Gallery, as well as I’m with Stupid, a collaborative installation executed with his wife, Melba Price, and his daughter, Oakley Tapola, at SOO Visual Art Center, Minneapolis. He received the McKnight Foundation Visual Arts Fellowship in both 1994 and 2000. He currently serves on the faculty at St. Cloud University in Minnesota.

About the interviewer: Originally from South Dakota, Minnesota artist Ruben Nusz was raised by cowboys and later graduated Summa Cum Laude from the University of Minnesota. In 2003 Nusz directed a feature-length documentary that toured the festival circuit. He has exhibited mixed-media works at the Minnesota Museum of American Art, Rochester Art Center, Art of This, Fox Tax Gallery, Umber Studios, and Hopkins Center for the Arts.