Use Your Illusion

Sean Smuda on Eric Frye's series for Midway Contemporary Art on "compositional epistemologies," an erudite survey of the fusion of technology, composition and performance exploring the intersections of time, knowledge, self-hood and sonic space.

Eric Frye’s modular synth performance at Midway Contemporary Art last March totally did it for me. Juicy sonic granules coasted up and down parabolas of volumes and scales, accreting nuance and morphing along the way. Time itself felt plastic, both still and poised to relaunch itself in multiple variations. His music seemed to echo visual work I’d been making and even what I was reading (Gravity’s Rainbow): slight forward motions with twisting parallel depths merging and transcending their structures. I shared this vibe with an acquaintance next to me who does Krautrock-style pulse trance. He replied: “This is the kind of thing that drives me crazy”.

Almost a year later, writing this, I am happy to say it is the kind of thing that can now drive everybody crazy, as Mr. Frye has organized Exploring Compositional Epistemologies (ECE), nearly a month of programming from mid-January through mid-February, at Midway Contemporary Art. It’s a broad and erudite survey of the fusion of technology, composition, and performance, culminating in a reconsideration of the nature not just of sound but of the individual’s point of audition. As per the title, the series aims at the exploration and use of knowledge itself.

ECE demonstrates that time-as-sound is sculptable, smashing ideas of progress and progression into the unlimited, individualized patterns and tones that technology affords. The series’ cast of artists skews between loose and rigorous institutional affiliations, and this can be heard in their performances, which while sometimes dry and structural, nonetheless shake the idea(s) of music through their research. It is not an ephemeral spirit of the times they’re chasing, and ECE’s programs may not be as entertaining or immediately signifying as a basement rap show with laptops (what is it about that other!). However, they’re more sublimely and horrendously about the hive mind and its dissonances, which via these laptops we are always almost becoming.

James Hoff kicked off the ECE series, speaking to a packed library and offering wry, meticulous accounts of reclaiming history: as idea as book as exhibition as performance. By reprinting seminal publications such as Avalanche (1970-1976) he has succeeded. So close to the originals are these reprints that a measure of this success, according to Hoff, happened when he saw that artist Vito Acconci had shelved his fresh set of Avalanche, indicating that something was not quite right about it. Such a confluence of past and present iterations speaks to the eerie nature of time travel, though in music it would simply be called da capo (da tutti capi: Vito! Seedbed, once more, with feeling). If repetition is the diffusion of an idea in all mediums, as David Joselit has written about Duchamp, then to repeat/reprint ideas in the medium of time is perhaps their ultimate diffusion. Hoff’s Primary Information project helps root culture’s need to be self-aware in order to grow, particularly in this age of media abundance where so much is referenced without attribution or context (insert – pop artist “borrowing” from conceptual artist, or fine artist being “appropriated” by conceptual artist – here). Acconci, having since moved beyond his 70s performances into architecture, may have felt disturbed by seeing his ghost appear in this eternal return; perhaps now he better knows how his audiences felt. Either way, he (with Mr. Hoff) is releasing over 40 hours of audio that accompanied his performances, and they’re essential to a fuller and more visceral understanding of time and presence.

After an hour’s seated presentation, Mr. Hoff began to musically unravel contemporary times in Midway’s main room with a 20-minute, glitched-out performance of Blaster. Sans ghetto and with video game overtones, its score of dance beats infected with computer viruses (he also produces their visual equivalents) was deliciously dance-worthy. In fact, standing in the main gallery, many at Midway struggled with their twitching limbs’ wanton desire to rupture the still-fresh lecture’s archival patterns. (Disco balls may have tipped the balance on that (speaking of ’73) but, in the end, history prevailed like 007’s cocktail.)

Guerino Mazzola

A week after this raucous trembling, it was only appropriate that the lively Guerino Mazzola should appear next in the series. As we talked beforehand, he rejoiced in his appetite for free jazz, which recently had him touring Japan where its acolytes play “incredibly fast, like nowhere else.” An acclaimed writer/musician, author of over 22 theoretical tomes and as many CDs, Mazzola is Professor of Creativity and Mathematical Music Theory at the University of Minnesota. Walking the talk, he led his lecture with a short video of one of his piano performances, an explosively percussive piece in the vein of Cecil Taylor. From there he expounded on the music program Rubato, which he has been involved with authoring. The program allows a composer to invert, extend, shrink and control tones and compositions – it’s an incredible micro/macro time-bending tool. To paraphrase him, “things that would have taken Boulez months to rewrite can now be done immediately.” This immediacy is in service of the hand’s pitch, onset, and position from which its mapping and gesture can be used for finer control of instruments — including surgical ones. Rubato has 10 to the 37th power of possible transformations, at least enough to recreate a Cecil Taylor performance if not the humorous/shamanic dances he sometimes leads them with.

8-channel performance

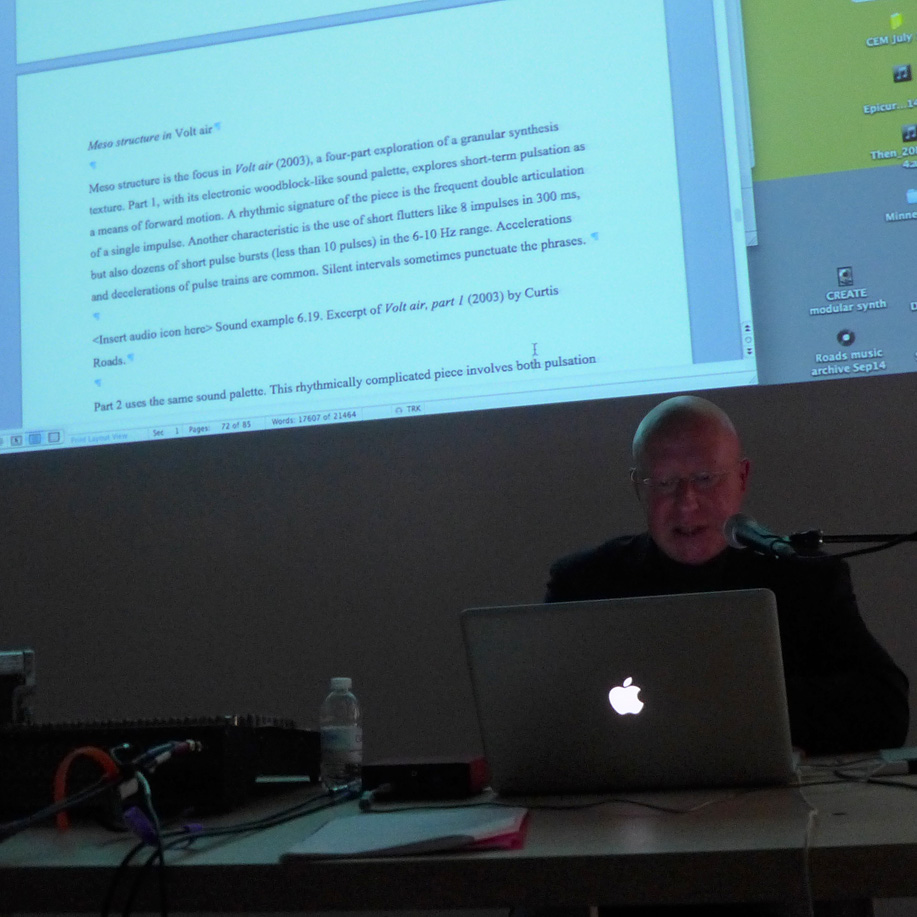

The main act of this day’s series was a heavyweight champion of computer music: Curtis Roads. The first person to implement granular sound processing in the digital domain, Roads is also cofounder of the International Computer Music Association, amongst a list of accomplishments that more or less spans and defines the medium. Starting with a video of the AlloSphere at UC Santa Barbara, where he teaches, he brought us inside this three-story, anechoic sphere’s immersive projection of a giant brain. Over 140 channels of sound and wrap-around video broadcast harmonic pings related to blood density, accompanied by real-time data streams from electronic microscopes. In center of the AlloSphere, a suspended bridge holds up to 20 scientists guiding surgical probes with electronic wands; from the platform, artists may conduct music or build visual projections from the insides of projected atoms.

Curtis Roads

Following this opus dei, Roads offered a dry, careful reading from his forthcoming book, Composing Electronic Music: A New Aesthetic. With the demeanor of a contemplative Buckminister Fuller, Roads’s self-reflective monotone sank deep into the fundamentals of sound creation, as he related physics to electronic composition from a chapter on rhythm: “…short-term pulsation as a means of forward motion…” culminates with “… stimulating electrical storms in the brain.”1 Unfortunately, his punctuation of sonic examples revealed shorted connections that multiplied from stereo into eight-channel problems. Staying the course for the Big Bang-jonesing audience, an electronic fix eventually brought his performance to a re-start. What his compositions Epicurus and particularly Then enacted was primordial, like being in a planetarium where a show on the first moments after Creation was playing. The evolution was fascinating, solitary, and not unlike the special effects from a sci-fi film. Though Roads’s depth is incontestable, I prefer the compositions of Iannis Xenakis in matters of spatialization, such as the epic Legend of Er. Though this may seem to favor the mythic over the primordial, for me they are part of the same Mobius strip, which includes I.X.’s elemental Concret PH (originally broadcast in 1958 in 11 channels over 425 loudspeakers in a building executed by the composer).

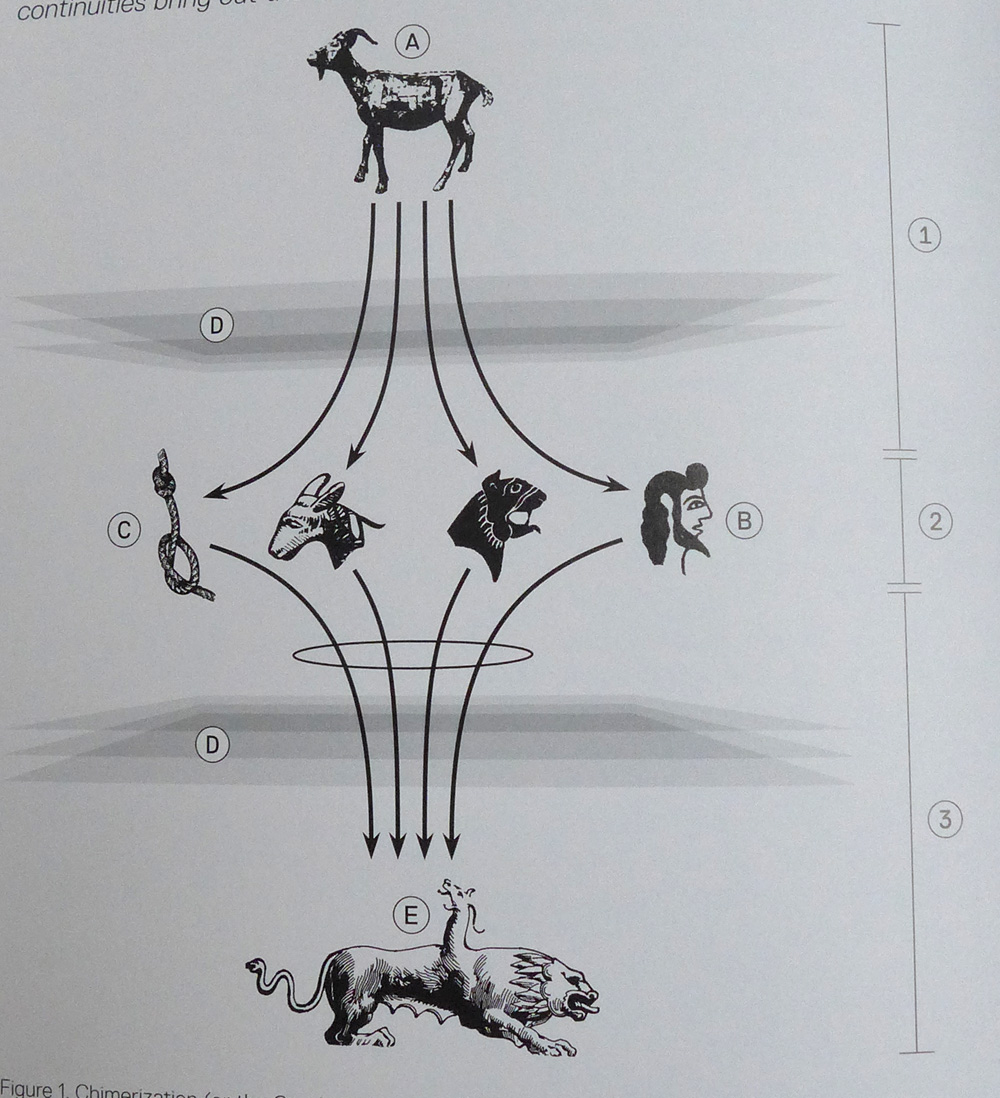

My predilections were well served by Florian Hecker’s installation Chimerization. His piece takes its name from contemporary genetic research, which takes its name from the chimera, a mythic (female) lion-goat-snake-headed beast. The installation’s sonic tropes parallel chimera research, which combines cells from multiple species to trace distinct embryologic development in new, non-hybrid, life forms. In Hecker’s three-voiced composition, “each carrying its own respective space within the beast, one voice manages, describing the constitution of the chimera.” 2 This voice wended through isomorphic tones of surface and undercurrent, arcade progressions, and gravelly textures that dissolved and reappeared from a triad of speakers suspended at throat height.

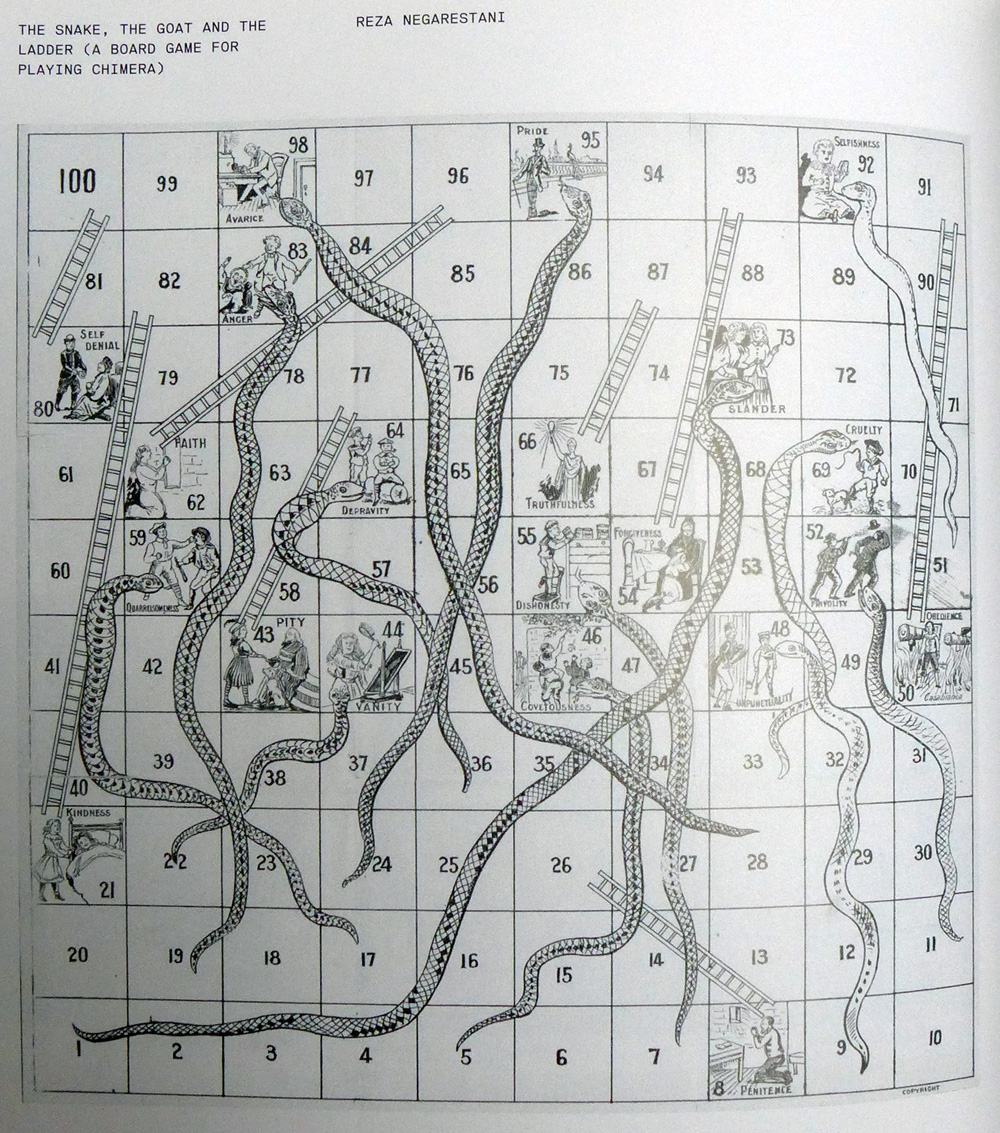

Philosopher Reza Negarestani’s libretto, entitled “The Snake, the Goat and the Ladder (A board game for playing chimera)”, described the collective beast from each voice’s perspective, articulating another definition of chimera — illusion, of the sort that hovers overhead when looking down in a reflecting pool and whose living description is incomplete except through the dissonance of all voices at once. The libretto’s mirror moves also derive from an Indian game of karma and kama (destiny and desire) — the same game that was transfigured by the English into one of redemption and salvation and later known to most as Milton Bradley’s Chutes and Ladders. The music “dismisses any humanist model of hearing”3; Hecker’s ideal listener is an active participant, carving out time, space, and attitude with attenuating turns of head, body, and thought. She may also play this game at home (it has been available as a two-channel download since its premier at Documenta 13 in 2012). This listener will know she’s winning when she “…turn(s) –analytico–synthetically–a goat… worthy of singing the ‘hymn to cliffs’–that is, a post-pandemonic composition wherein ascension and descent of profound continuities bring out the most chimeric landscapes.”4 In the midst of this postmodern topological shifting, blurring, and differentiation of philosophy, genetics, and sonic disorientation, I found myself removing articles of clothing and beginning to dance. Perhaps the libretto had insinuated itself into my brain:

“Snake: It is imperative to rediscover the figure of the player.

Ladder: And its voice, its status and its expression…

Snake: “chimera is a man”

Ladder: “And chimera is not a man”

Snake and Ladder: At the same time” 5

I had become a “…profile of the modern abyss’s unbound relation to itself.” 6

It should be noted that the “brain” of the Documenta exhibition was a piece of fused glass, ivory and terracotta from a bombed-out Beirut museum. Psychically, I must attribute my actions to war’s insanity and a will to break the hive mind’s damning illusions! Social strictures aside, Chimerization’s “absence of any lattice to which we can be bound” 5 and “using a sound environment to address the physiology and the psychology of the listening process itself” 6 is a way of moving into dimensionalities governed uniquely by time, desire, will, and chance: a somewhat combative but satisfying vision quest for pure, otherly consciousness –sci/psychedelia-concrète.

Eric Frye (right) introducing Roc Jimenez de Cisneros (left)

Furthering this inquiry into consciousness, Roc Jiménez de Cisneros came in askance, determined to define its lapses. Researching dictionaries, philosophers, and the audience, he exposited a taxonomy of holes: in relation to an object in space; as shadows in light; fidelity gaps in mp3s; and as silence – the sound of time passing. As holes presuppose the existence of something, they are an absurdity, an interruption leading to … : calculating the relation of an object to regions in space; sensing one’s doubling; degenerative bodies in space; and experiencing the resonance of that which was. Closing his talk with a 1955 Looney Tunes animation, The Hole Idea, fireworks from the Loppet exploded outside, perfectly punctuating his “taxonomic insurrection” of space.

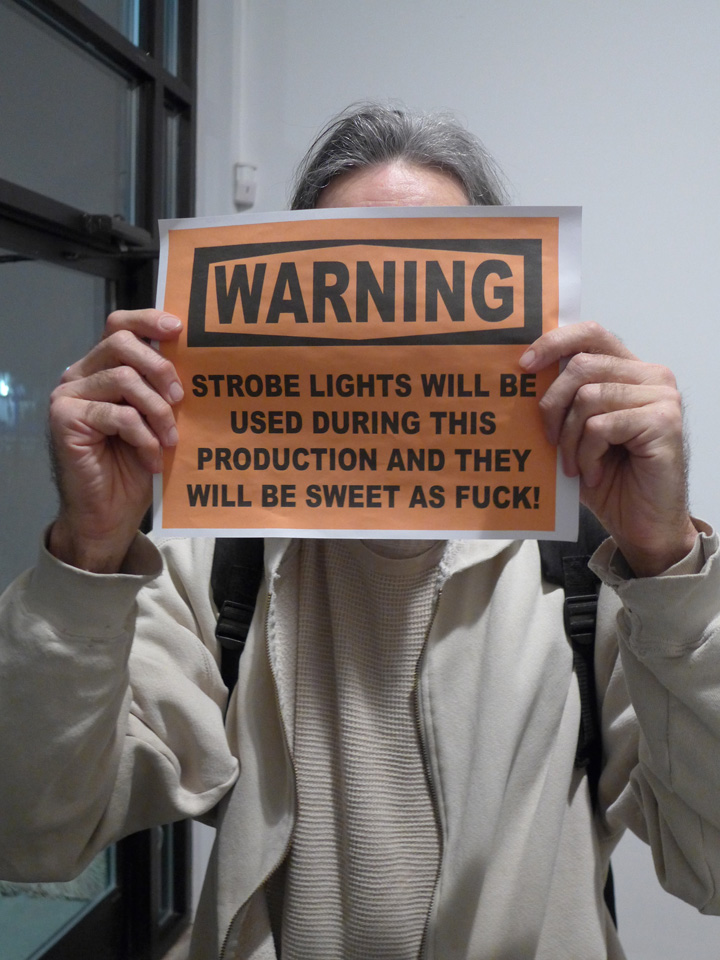

Building quickly to an intermittently, intensely pullulating bass and 3,000k strobe light, Roc’s Holes in Sound was of a density that only certain kinds of acid might dissolve. Walking amongst my fellow auditors during the performance, judging time and space felt in that moment like a perilously staccato riddle. Someone in a bunny suit came in, checked out the musician, stood in the crowd, and vanished. I seemed to be disappearing, like an insect slowly being pinned to a Super Mario collider. Finally gathering my body between the speakers, I articulated my face with eyes closed, which produced a series of Hiroshima-like masks that I can still see.

And then it was over. Climbing out of the sonic-bomb crater, senses muted and jolted, I stumbled across some non-official signage that read: “STROBE LIGHTS WILL BE USED DURING THIS PRODUCTION AND THEY WILL BE SWEET AS FUCK!” I hurt so hard I laughed.

Ultimately the ECE series ascends and falls under the math theory scaled to sound by Mazzola in his book The Topos of Music 7. In it, he writes of the logical and transcendental location of the being and existence of music, which can also be associated with a synthesis of geometric and logical theories. I interpret this as both a sensorial and meta- sense of place – a geography at once specific, virtual, and ever more manifold. This topos may include a slew of theories, sets, and histories folding in on, resonating, and breaking out of themselves, creating sounds that drive us crazy enough to challenge our preconceptions of whatever place in time we find ourselves.

The series also raises questions of genetics and behavior modification through many of its artists’ use of recognition algorithms. Translating worlds beyond immediate perception, their outputs are ground zero for psychic and physical adaptation into scenarios increasingly controlled by data. Meta-frackingly incisive for art and surgery in controlled topologies, the work demonstrates that there is — as is proven by surveillance, market glitches and military drones — a true and horrendous margin for error. That’s the real chimera.

Coda

Reflecting now on Mr. Frye’s performance of 3.1.14 at Midway, it holds up for me as a reductio-absurdum of the basic elements of its medium: tone, rhythm, volume, and melody: the kind of space from which all art morphs.

Footnotes:

1) from Composing Electronic Music: A New Aesthetic by Curtis Roads, Oxford University Press, (forthcoming)

2) Grayson Currin, Florian Hecker Chimerization, www.pitchfork.com, 1.4.2013

3) a chimeric visualization of sound, act.mit.edu, 6.27.2013

4) Florian Hecker: Chimerizations, by Florian Hecker, Reza Negarestani, Stefan Helmreich, Catherine Wood, pp 203, Primary Information, 2013

5-7) Ibid, pp 199-200

8) Nick Cain, Florian Hecker’s Chimerization: Surround sounds, thewire.co.uk, January 2013

9) The Topos of Music: Geometric Logic of Concepts, Theory, and Performance, by Guerino Mazzola, Birkhäuser, 2002

Noted exhibition and performance information:

“Exploring Compositional Epistemologies: A Series of Notional Synthesization on Topological Morphologies and Heuristic Gestures in the Realm of Sonic Language,” is organized by Eric Frye and presented in a series of related events at Midway Contemporary Art from January 16 through February 14, 2015

Sean Smuda was historically predetermined to write this article, being genetically engineered by philosophers and musicians who can’t quite account for his chimerization of dance, performance, and visual art. His work is in the permanent collection of the Walker Art Center, his studio is always open to epistemologists, and he has played in noise/improv bands for almost a Christ’s age.