THEATER: Looking Over “Fences”

Playwright Matthew Everett weighs in on Penumbra Theater's ambitious production of August Wilson's classic play, "Fences." Like the other productions in Penumbra's CENTURY CYCLE, it doesn't disappoint.

THERE OUGHT TO NEVER BEEN A TIME CALLED TOO EARLY. Lets get the main question out of the way up frontshould you see Penumbra Theatres production of Fences?

A Pulitzer Prize-winning play by August Wilson, directed by Lou Bellamy, and acted by an ensemble of Penumbras best? Of course, you should go. Just like The Piano Lesson and Gem of the Ocean before it, Fences is another exceptional entry in Penumbras plan to produce, within five years, all ten of the plays in Wilsons Century Cycle, chronicling the African-American experience across the ten decades of the 20th century.

Fences offers up a slice of the 1950s in the Hill District of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to be exact. The action centers on the home of Troy and Rose Maxson; the unfinished project of a fence languishing in the front yard isnt the only fence, literal or metaphorical, to go up or come down over the course of the play.

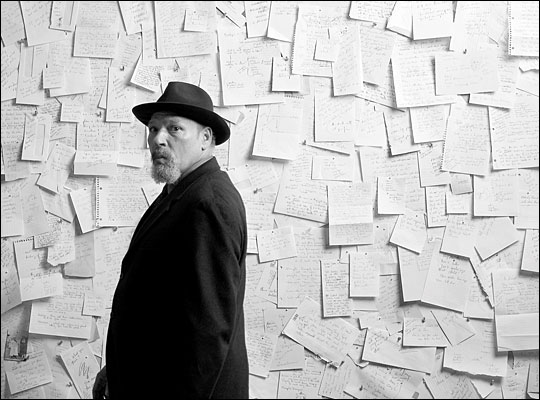

Playing Troy is actor James A. Williams, and his is a mesmerizing performance. Its good to have Williams back in town and on the Penumbra stage again, if only for a little while (hes off to Nairobi in 2009). Troy, like many of Wilsons characters, is caught in the changing tides of history; some of those changes come along too late for Troy and some too soon. A star in the Negro baseball leagues, Troy is too old to reap the color-barrier breaking benefits of Jackie Robinson’s successes in major league baseball. When college football comes knocking for Troys son Cory (James T. Alfred), he hesitates; Troys resistance is partly rooted in concern about the possibility of dashed dreams for his child, but it’s largely the bitterness left from his own thwarted career in sports that gives him pause. The ensuing battle of wills between father and son escalates with a fierceness that is often unnerving to watch.

Troy also struggles to make the most of the career hes been handed, in garbage collection. When he makes waves with the union over the fact that only white men are allowed to drive the garbage trucks, while the black men collect the trash, Troy isnt given the walking papers others fear are coming for him. Instead, he’s promoted to the drivers seat himself. But even this prize is tinged with loss; his good fortune has the unexpected downside of disconnecting him from his friends and former coworkers, including his sidekick Jim Bono (winningly played by Marion McClinton).

________________________________________________

There are no easy villains in Wilson’s rendering of these dynamic charactersall their actions seem understandable, if regrettable.

_________________________________________________

Though his personal life, at first glimpse, seems charmedhe shares his home with a promising son and a doting wife Rose (Elayn J. Taylor) Troy is tempted to stray. What starts out as a mere dalliance evolves into something Troy finds he needs almost as much as his life with Rose; and when the other woman becomes pregnant, he is forced to bring the affair into the light. The pregnancy and resulting child have dire consequences for Troys relationships with both of the women in his life. One of the many masterful strokes in Wilsons script for Fences is the way in which he handles the emotional nuances of this affair. There are no easy villains in his rendering of these dynamic charactersall their actions seem understandable, if regrettable. Big praise also has to go to Elayn J. Taylor for her portrayal of Rose; hers is a luminous, earthy presence on stage, a fine complement to Williams’ Troy. Taylor’s rendering of Rose is subtle and layeredshe’s a voice of reason when faced with volatile family situations, equally quick to laugh during playful scenes and to lash out when betrayed by those she loves. Taylor’s embodiment of Rose is a fitting foil for the often foolish men in this play.

James Craven, as Troy’s brother Gabriel, supplies the spiritual/supernatural element which is so key to the larger-than-life, archetypal quality that marks a Wilson play. As a result of a head injury suffered while fighting in World War II, Gabriel now considers himself the angel Gabriel, blowing his horn to signal the opening of the gates of heaven.

_________________________________________________

Since we’re living in a time when treatment of veterans (often men damaged by war just like Gabriel) is becoming an ever more pressing moral concern for this country, Wilson’s sketch of the issue feels especially timely.

_________________________________________________

His delusions seem harmless enough, but the family around him is more forgiving than the larger society, and he often runs afoul of the law. Gabriels disability checks have made home ownership possible for Troy, and so, in gratitude as well as brotherly affection, Troy fights for Gabriels ability to live on his own terms for as long as possible. But it is a fight they are destined to lose. Since we’re living in a time when treatment of veterans (often men damaged by war just like Gabriel) is becoming an ever more pressing moral concern for this country, Wilson’s sketch of the issue feels especially timely. (Such is the timelessness of a great play that it can be seen in so many different ways, newly relevant to changing contexts over time.) James Craven takes the tricky role of savant and pulls it off with his usual no-nonsense style. In fact, one of the joys of seeing Penumbra tackle all ten of August Wilson’s plays is getting the chance to see company regulars taking on such a wide range of meaty roles.

Like Gabriel, Troy wages his own spiritual battle in Fences; throughout, the character is convinced he’s fighting for his life with the angel of Death itself. What seems, at first, like just another colorful story crosses into the more ambiguous territory of shared delusion; more than once, the audience hears the sound of dogs (hell-hounds?) approaching and sees a ghostly light encroach upon the entrance to the house. Troy fights these harbingers off more than once in the course of the play, but still death touches him closely through the fates of others.

Actually, the point in the play where Troy finally loses his battle with Death, as all living things must, is the one part of this production which puzzles me. The resolutions to Wilson’s other plays, like The Piano Lesson and Gem of the Ocean, aren’t obvious, but they seem natural, like they’re embedded in the stories’ very beginnings. The finales make a satisfying kind of sense when they unfold. Here, in Fences, the end of the story is trickier. As the penultimate scene closes, the audience sees Troy locked in yet another showdown with the ghostly light of Death. But in the final moments of the play, the story leaps ahead eight years. We learn that Troy is dead, but only recently so. Given the skill of all the artists involved, from Wilson himself and on through the ranks at Penumbra, this must be a deliberate choice – not to show Troys final, losing, battle with Death and to leave the details of his last years in the shadows. But the decision, by both playwright and production, to leave the audience wondering about Troy’s final days, nonetheless, leaves me scratching my head.

Sure, it’s interesting to see all the other characters eight years on down the road. Its enlightening to watch them try to make their peace with Troys often combative memory. Perhaps when the audience last sees Troy, he is already spiritually deadbereft of friends, children, and the women who loved him. The men of Troys generation, just before the Civil Rights Movement hit with real force and changed America forever, were no doubt sometimes lost in just this way, striking out with equal venom at change and at the chances they were denied. Perhaps the tragedy of the inevitable tide of such social change is that some people arent buoyed up, but are crushed under its waves instead. Maybe thats what Wilson is driving at with this final plot choice in Fences. The audience gets to see Troy the last time he has any fight left in him; he may live on for another eight years after that battle, but he never really lives again.

Go see Fences for the amazing performances and the torrent of beautiful words that Wilson puts in his characters’ mouthshe elevates everyday conversation into the realm of poetry. Wilsons words have power and motion and a driving force that makes Fences a real thrill to watch in action. Very highly recommended.

About the author: Matthew A. Everetts play Leave is being performed by afterdark theatre company Thursday, September 11 and September 25, 2008, 7pm, at the Bryant Lake Bowl. Matthew is the recipient of a Drama-Logue Award for Outstanding Writing for the Theater, and he is a three-time recipient of support from the Minnesota State Arts Board. He holds a Master of Fine Arts degree from the Yale School of Drama. Magicword Theater recently produced a popular double bill of his short plays The Bronze Bitch Flies At Noon and Dog Tag as part of the 2008 Minnesota Fringe Festival. His blog about the Fringe can be found online at Twin Cities Daily Planet. Sample scenes, monologues, and further information on Matthew and his work can be found online at www.matthewaeverett.com and, of course, at www.mnartists.org/matthew_everett.

What: Fences by August Wilson, directed by Lou Bellamy

Where: Penumbra Theatre, Saint Paul, MN

When: Performance run extended through October 19, 2008. For information on show times, directions, and ticket reservations, visit www.penumbratheatre.org or call 651-224-3180.

And dont forget to mark your calendars for the next installment in Penumbras Wilson cycle Radio Golf – May 5 through June 7, 2009.