The Artist as Disruptor

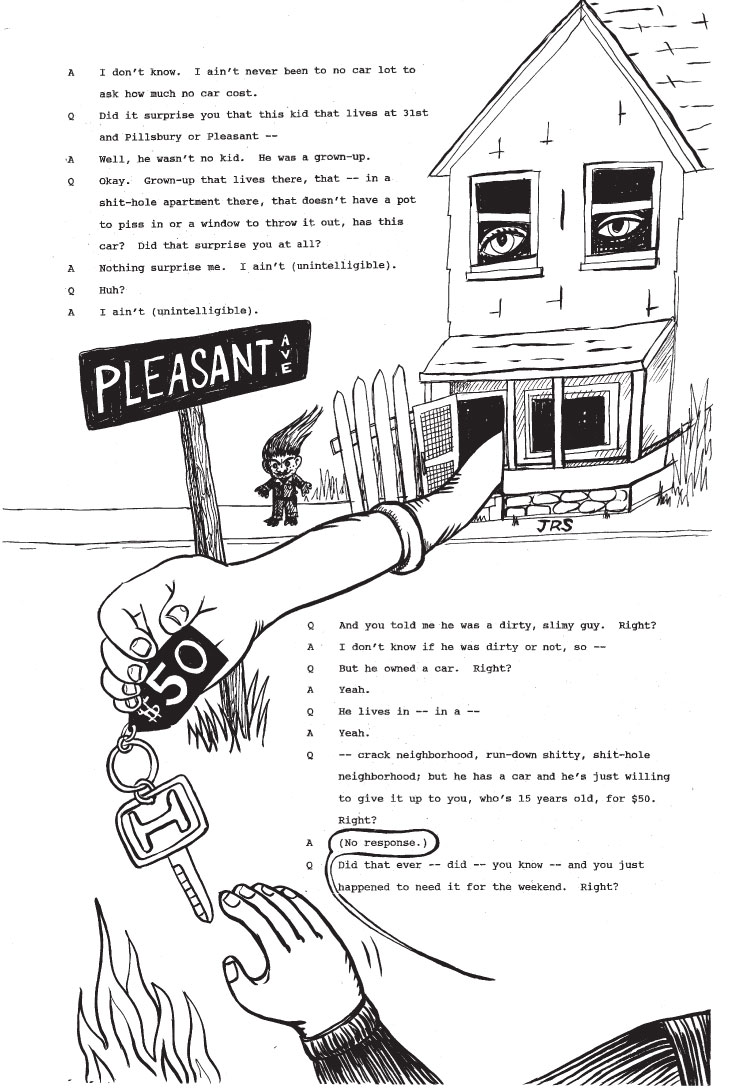

A cohort of Twin Cities-based comic artists gathered this spring at the print shop Beyond Repair to illustrate a leaked transcript of a 1996 police interrogation by then-Sgt. Bob Kroll (now president of the Mpls police union), who was questioning a 14-year-old African-American boy accused of stealing a car. Sam Gould (of Beyond Repair and Red76), a principal behind the comic's recent publication, weighs in on the provocative project's still timely context, intentions, and repercussions.

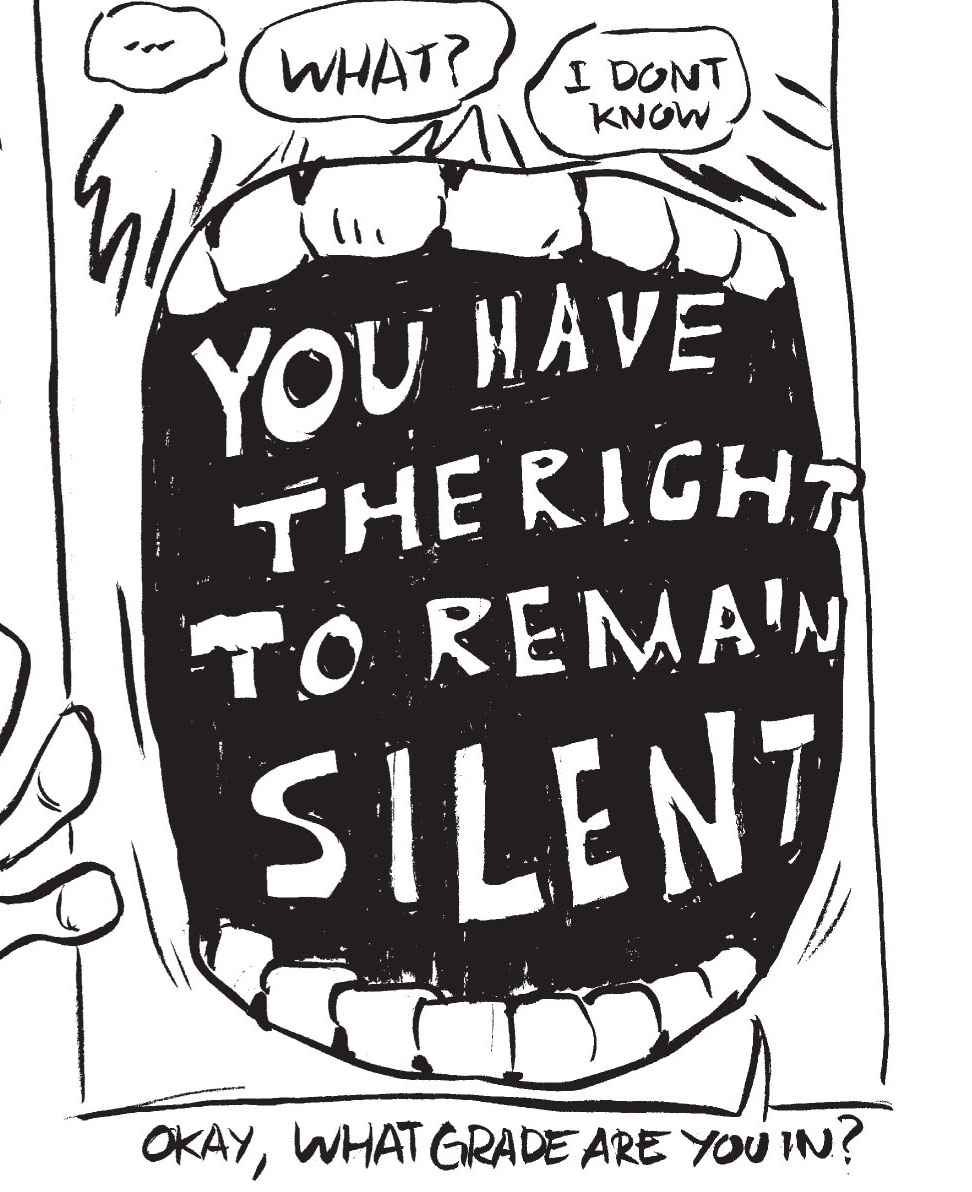

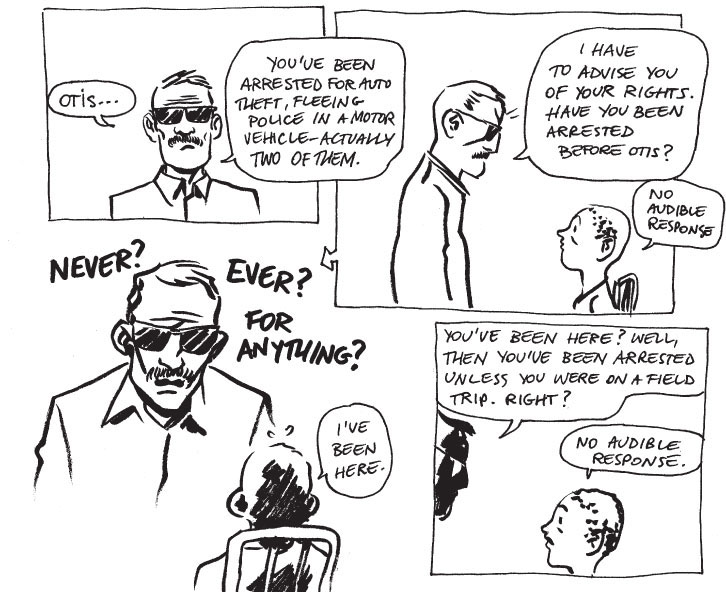

This spring and summer, a collaborative team of artists published a scathing illustrated zine, “Sgt. Kroll Goes to the Office,” intended to offer “a comic retelling of police union president Bob Kroll’s interrogation practices.” The text of this multi-artist comic is drawn from the leaked transcript of a recorded interrogation from 1996: then-Sgt. Kroll (who was elected President of the Minneapolis police union in 2015) was recorded questioning a 14-year-old African-American boy who was accused of stealing a car. The transcript was passed around through back channels for a time, but never got widespread press attention; it was also leaked to Sam Gould, editor of the publication platform Red76 and proprietor of Beyond Repair, a small print shop and experiment in civic publishing that has set up shop in Midtown Global Market.

In the tradition of muckrakers before him – from Thomas Paine and Hogarth to the Yippies of the ’60s – Gould decided to poke the bear. Using the tools at his disposal – ink, paper, rage, wit, moxie – he enlisted a number of artists to create a satirical piece that might shine a brighter light on both the content and tenor of the interrogation, and also the larger issues of policing and power, the “school to prison pipeline,” race and “community policing.”

According to the zine’s afterword: “As a means to create and distribute a portrait of Lt. Kroll’s beliefs, methods, and personal conduct,” Beyond Repair and Uncivilized Books gathered a group of Twin Cities-based artists at the small print shop for an all-day, collaborative “book sprint” to illustrate the interrogation transcript in comic book form. The dialogue in the published zine isn’t embellished or edited for effect, but rather quoted directly from the text of the received transcript. The finished comic is now available for free in Beyond Repair and being passed, hand to hand, around the city.

I had a conversation with Sam Gould about the project, its context, intentions, and repercussions. His responses are below, as are selections from the newly published zine and a link to the full work online.

Susannah SchouweilerWhat are the circumstances surrounding the transcript related in the comic, “Sgt. Kroll Goes to the Office”?

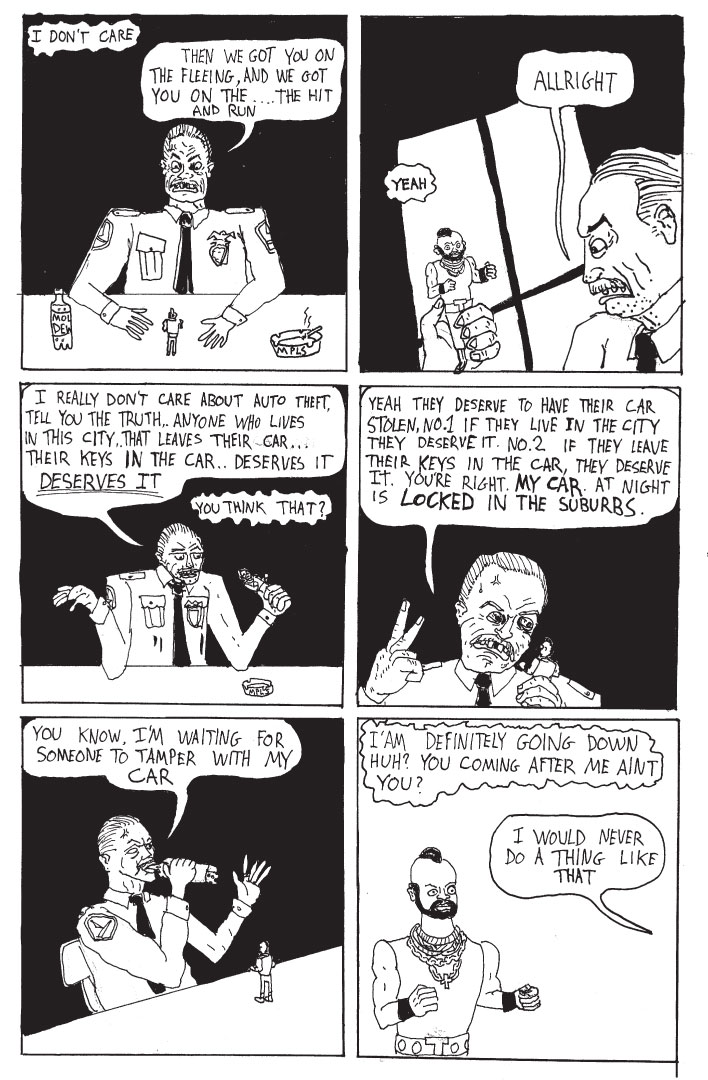

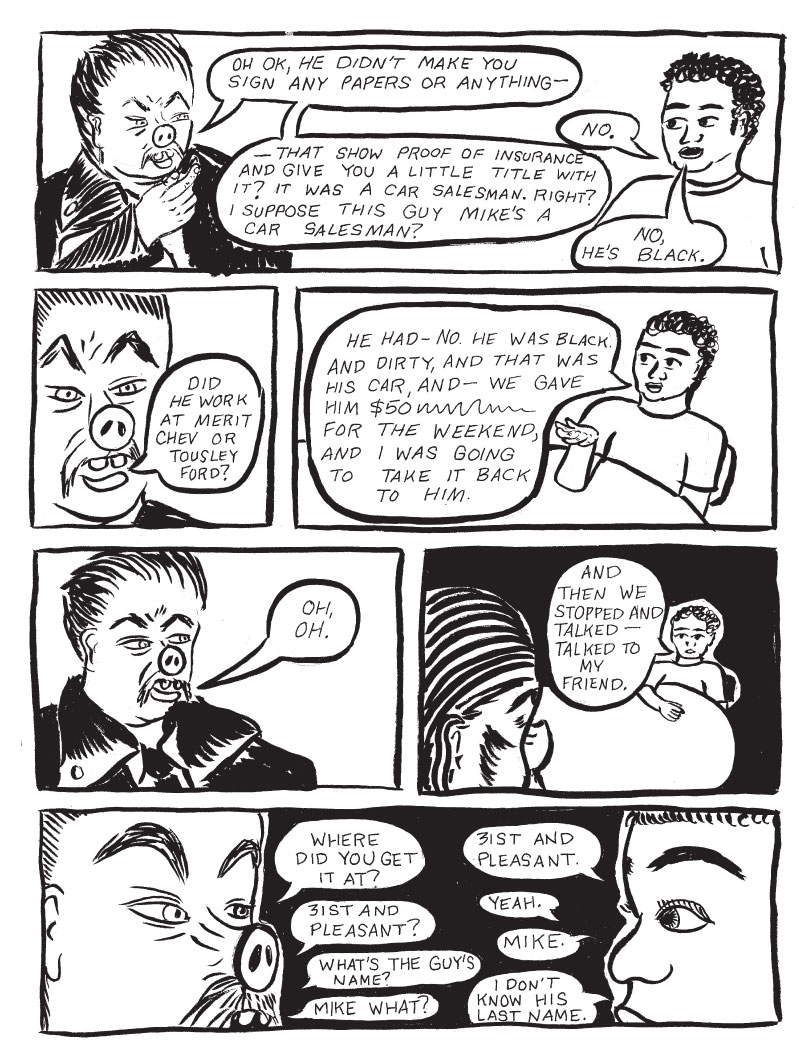

Sam gouldIn 1996, Otis, a 14-year-old African-American boy, was picked up for riding in a stolen car. He was interrogated by Sgt. Bob Kroll, of the 3rd Precinct, which is the precinct in my neighborhood here in South Minneapolis.

For folks who are aware of the history, and infamy, of Bob Kroll, reading this transcript is both unsurprising and a gift, in that it’s a private moment made public that reveals so much of what we expect of him. For those unfamiliar with now Lieutenant and Police Federation President Kroll, it will likely come as a shock.

The transcript illustrates a dismissive, bullying man who is contemptuous of the child in front of him, notably a black child. Knowing Kroll’s links to White Power groups and ideologies, and his history of racially charged attacks while on duty makes the narrative even more insidious. Kroll is linked to a white supremacist hate group, a cop motorcycle club called City Heat, which has been singled out by, among others, the Anti-Defamation League for its racism and anti-semitism. He’s been accused by fellow officers of wearing a “White Power” patch on his jacket to work and sued by fellow officers of color for hate speech and discrimination. These very character traits play out in the transcript’s narrative. Kroll demeans the child, intimidates him; he tells him that, one day, he’ll be killed by a police officer. In the end, he tells Otis that he doesn’t even care whether he committed the crime or not, that it’s up to him — a kid — to beat the charge and save his own skin.

While all of this would be horrible, if not typical, of what we might expect from a police interrogation, the fact that the document is a record of a cop railroading a child paints another portrait, too: a system on fire, assisted by the repetitive, mindless mechanics of officers such as Kroll, who do not see human beings in front of them, but raw matter, ready to burn to fuel the machine. The incendiary disappearance of Otis, and other children like him, from public voice and civic responsibility energizes Kroll, and in turn, fuels the system.

While the systemic function of the machine and its production stay the same, it’s the output that varies. And with that in mind, what’s important to shed light on is how, when this attack occurred it was a reflection of its time, but also how that moment lives on and has become streamlined — and augmented — through actors within that same continuing narrative. The story of this interrogation is both deeply local and personal as well as national in scope, as it begins at the apex of the militarization of the so-called “war on drugs,” funded (and notably de-funded through the eradication of an array of social services) in good part by the Clinton Crime Bill.

Trauma lives in the body, and the body politic, as represented through our institutions — criminal, legal, electoral — carries those same traumas and instrumentalizes them through forms of policing, policy, legal proceedings, and the like. What the transcript, and in turn the comic, illustrates is the literal embodiment of these local and national stories becoming streamlined and institutionalized. They are played out in the characters of living people like Bob Kroll and Otis. And so, inasmuch, it is important, as it concerns our lives here and now in Minneapolis, to understand the local elements of this continuing narrative.

Arguably, we can say this narrative begins on September 25th, 1992 when patrolman Jerry Haaf was executed while getting a cup of coffee at Pizza Shack, a known cop hangout on E. Lake St. and a short walk from where I live. The narrative that plays out within the comic takes place four years later. It’s important to shed light on what went on within those four years, and how the escalation of aggression, and so-called “over-policing” — others might call it “state terror” — which occurred in-between those years has solidified into a culture maintained by cops like Kroll within his position as President of the Police Officers Federation. From the accounts of people I’ve been speaking with, prior to and in the aftermath of the release of the comic, who had firsthand knowledge of working with Kroll in the 3rd Precinct and living within the precincts reach at the time, the justifiable trauma experienced by Kroll and his fellow officers after patrolman Haaf’s death turned feral. Their trauma provided them an avenue into outright war with the neighborhood; many within power felt the product of their trauma justifiable, especially as more and more federal and, in time, state and municipal dollars were being funneled into police budgets both in Minneapolis and around the country. The conduct and legality of the behavior of officers of the 3rd Precinct, and in the full MPD, was inconsequential compared to the job they believed they now had a mandate to act upon.

The story which unfolds in the comic exists within this social landscape. And that social landscape is broad and timeless. It’s this energy, this mindset, that lies at the heart of the conversation, since the killing of Jamar Clark, here in Minneapolis. It’s not that such tension wasn’t already present; it’s simply that, the country over, “business as usual” by our police forces is no longer being taken for granted. And, in the case of Minneapolis, old stories are painting a portrait of how we arrived at our present moment and energizing the subtext of the story we are presently living. At a moment when Hennepin and Ramsey counties are set to jointly fund over 150 new juvenile jails cells, at a cost of 18 million dollars, we cannot read the story of Kroll’s interrogation of this young boy as a narrative from the past. It’s part of an ongoing relationship, the stories of our lives, police and community residents, lived together. These relationships, in turn, build prisons, write law, set judgements of guilt and innocence, attack, belittle, and bully entire neighborhoods and publics.

At a moment when Hennepin and Ramsey counties are set to jointly fund over 150 new juvenile jails cells, at a cost of 18 million dollars, we cannot read the story of Kroll’s interrogation of this young boy as a narrative from the past.

ssWhat is your connection to the transcript? How did it make its way to you?

sgWhile I can’t speak to where the leaked transcript originally came from, but I can say it’s made the rounds before and, while everyone who has come into contact with it has reacted similarly, ideas about what do with the content of that transcript have often faltered. The reaction has been, “but it was so long ago.” What [our] action has allowed is the disruption of time. The medium [comics] here allows time to shift and flow differently. It’s a reading of history that allows us to see the present more clearly. As with the medium of comics, in general, it allows for a level of fantasy. And yet, word for word, it is reality. This divide between the unreal and the real seems to have struck people. These are Kroll’s words and actions. Nothing exists outside his own choices and methods. It’s a portrait of the school to prison pipeline, and yet the fantastical elements force us to question our assumptions. In the end, it all comes back to one point though — it’s all 100% true.

ssWhat is it about this incident, specifically, that has prompted you to act? Do you have a personal stake that motivates you to speak out about this kind of injustice?

sgI’ve spent the majority of my adult life engaging, in one form or another, in an art practice that is rooted at the intersection of art, politics, and social space. It’s allowed me entrance into a wide range of social landscapes and their histories. And so, quite naturally, a story along these lines would be something I’d move towards. But none of the work I’m interested in committing to is solely academic or theoretical. It all has personal, and lived, experience attached to it. If not I’d be objectifying Otis as much as Kroll did, if not with the same outcomes. Anything I’m devoting time to revolves around me attempting to work through ideas and problems for myself, as much as it does for any larger public which might be associated with those ideas or histories.

And so, specifically, when it comes to stories about the police and their interactions with the public, I can’t help but feel a visceral attachment to what I hear and see and feel as a result, because it is personal.

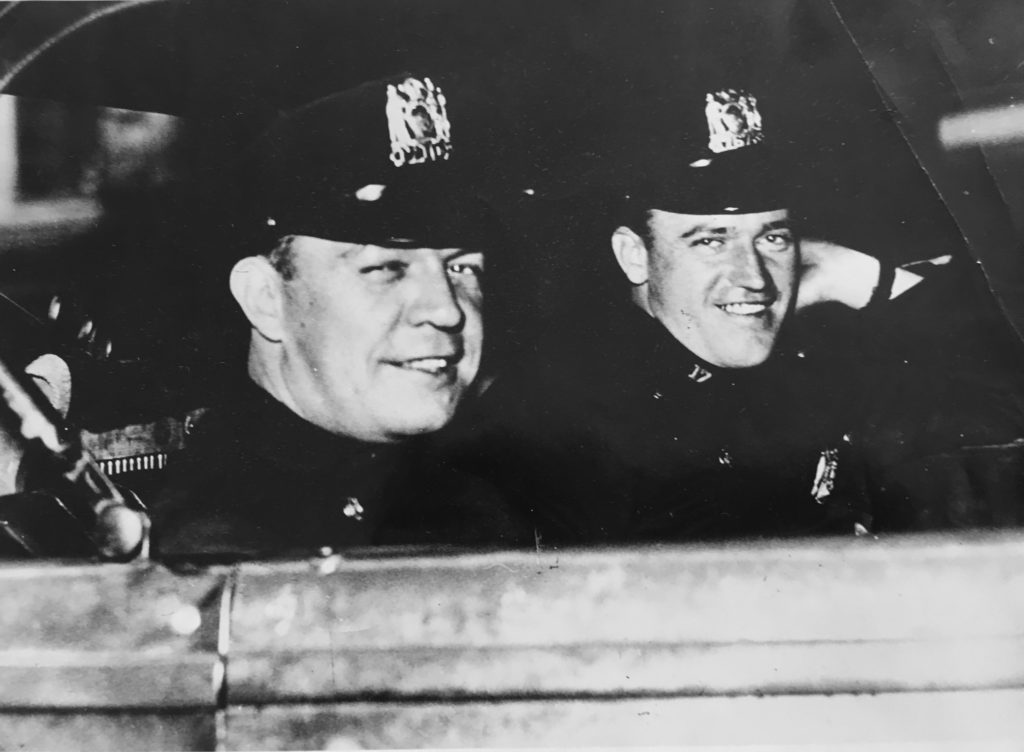

A family photo of Gould’s grandfather, an NYPD police officer.

Gould’s grandmother and great-grandfather Louis

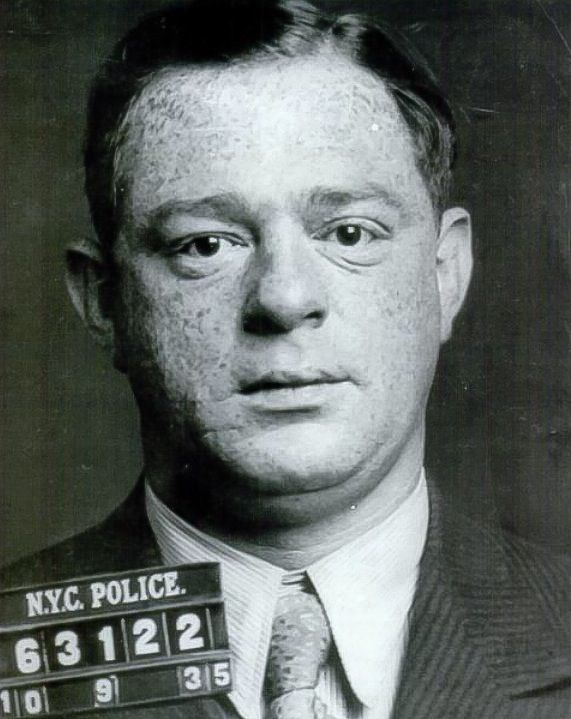

Gould’s great uncle, notorious hitman Samuel “Reds” Levine

In the one hundred-plus years either side of my family has lived in America we haven’t moved, until my generation, outside the area of the five boroughs of New York City. And when we arrived, on both sides of my family, there was not much opportunity for entrance or advancement for Jews and the Irish. One place, around the turn of the 19th into 20th century, that an Irishman could get a job was with the police department. My great-grandfather was NYPD. My grandfather as well. He passed away just before I was born, and I grew up with stories of him on the job, of his kindness and his courage, along with his, at times, dark sense of humor. My mother would tell me, when I was young, about how her father would tell her stories at the dinner table of “floaters” — bodies they’d fished out of the the East River who had bloated and ballooned up with gas — and how he’d have to pop them on the docks. All around New York, and especially within my extended family, this sort of dark, humorous engagement with reality was par for the course. Bad shit happens. It was a way to get through the day and I still have it in me. I can’t help but enjoy it.

As I got older I became more politically engaged with histories of power and its methods. And I had more interactions with power, often in the form of police acting as the authority of those in power, whose power was based on class and race/ethnic distinctions. The disconnection between the stories I heard about my grandfather and the actions I witnessed of police brutalizing citizens, or overstepping their authority, created a sort of cognitive dissonance that couldn’t be ignored. To my displeasure, increasingly, as time went on, this disconnect became more and more visceral for me, more visibly apparent in my day-to-day. Notably, I came into adulthood in the same time period the story of this comic takes place. I’m not much older than Otis is now, and yet due to the distinctions present within the comic, Otis and I live wildly different lives.

Along with this, I cannot avoid thinking about my father’s side of the family. My grandmother fled some of the deadliest genocidal activity in Europe prior to World War II. As a baby, her parents were able to escape marauding cossacks and the pogroms of Eastern Poland to arrive in New York City. Like many Jews, they settled on the Lower East Side, around Delancey Street, and later in East New York, in Brooklyn — both extremely tough, but vibrant, neighborhoods at the time. While the Irish were afforded assimilation into the policing class by that point, this sort of entrance wasn’t available to the Jews. My great-grandfather was an actor in the Yiddish Theatre, often performing alongside Jacob Adler in plays by Shakespeare translated into Yiddish for the working class of the Lower East Side. My grandmother, through where she grew up and her father’s occupation, was able to experience a wide swath of Jewish cultural life in NYC at the time. And, in her early twenties, she married into the extended circle of Murder Inc. An unavoidable offshoot, and form of protection, within her Father’s trade. Her brother-in-law, Samuel “Reds” Levine grew up with Meyer Lanksy and Bugsy Siegel, all kids just a little older than her. These were all folks who grew up in the neighborhood, and well into early adulthood (and maybe later), they were people my grandmother was familiar with. Especially Siegel, who was a friend she would socialize with when they both lived, for a brief stint, out in California in the early 1930s, just prior to the birth of my father. My Great Uncle Reds was Lansky and Siegel’s most trusted hitman. Infamous for his skills with an ice pick to the brain, he wore a yarmulke under his fedora, and refused to kill on the sabbath. These were all aspects of his life that my grandmother asked my father never to bring up on visits to Uncle Reds’ apartment, and which he always nevertheless asked about. Uncle Reds’ harsh reality was my father’s comic book fiction. Who shoves an ice pick through the back of someone’s brain for their job? Especially someone so nice as to always offer you fresh lemonade when you visit them?

So, however distant at this point, these relationships between race, class, power, authority, and assimilation have always been central to my worldview and to how I’ve come to understand myself, throughout my life. They’ve provided me a lens to consider where I am and how I arrived at where I am, or where I am not. And in relationships of power and institutionalism, I can’t help but read various actors as performing within a similar, and continuing, dialectical narrative. I don’t think I’m all that off either. From my perspective, there’s always been a very thin line between what is considered the law and what is illegal, between who is “in the right,” and who is “illegitimate.”

What we’ve been witnessing all too aggressively in the last few years, as if these relationships hadn’t existed prior, is a system’s ability, through the instrumentalization of state actors, to consider the consciousness, the personhood, of others as illegitimate, as out of place and order. And when, within this system, those actors step out of the role that has been written for them, we see that they are “put to heal,” as Hillary Clinton stated when she sought the funding that helped aggrandize the then-young officers like Kroll with tanks, grenade launchers, and other militarized weaponry.

What my friends who have returned from tours in Iraq understand, and what sadly, most officers of Kroll’s generation do not, is that the hyper-normalization of that type of “at war” mentality leads to trauma for all involved. Kroll believes he’s been at war for over twenty years. And let’s be honest. He has. What our aggressively masculine, militarized culture does not allow him to accept is that his every step is controlled by his own trauma, or to be more antiquated,his own “battle fatigue.” Kroll’s only saving grace is that his profession supports and fuels his trauma. The state and the police exist within a deeply codependent relationship. What we’ve learned from Iraq, as we learn again with each new military exercise, is that the psychic toll of war is extreme. The only difference is that the trauma of returning Iraq War veterans has amounted to an astronomical rate of suicides.

As regards the current state of US policing, the situation has produced a mirrored effect. Rather than killing themselves, officers like Kroll justify the murder and occupation of countless citizens as a method to avoid their own unchecked trauma from living in war. It’s important to remember that, they too, are foot soldiers, fulfilling the desires of those kept off of the front lines.

As an artist, my job is to disrupt. I take things apart so that they can be looked at in new ways. There are countless others who are qualified to reassemble.

SSWhy create this work now, and why address it in the form of a comic book?

SgWhen the subject comes up I’m often surprised by how many people don’t know who Kroll is, even among those who keep informed about local politics. As the head of the police union he, as per the job’s requirements, is the voice of the rank and file, as opposed to management. Though, even before he became head of the Federation he was extremely outspoken. So, from early on, and maybe this is simply my background speaking, if I wanted to know what the most vocal and hardline concerns of the police were, Kroll was the guy to look at. He’s representative of a certain, out-of-date, middle-aged policeman. Even the interrogation methods which he uses within the transcript are generations old and have been discredited as producing false confessions. There are, of course, younger cops who desire to be just like Kroll, but I’d argue that they are few. There’s an internal battle going on within police departments across the nation that the general public rarely sees. The “blue wall of silence” makes it so that the public sphere doesn’t often know the internal conflicts of law enforcement. But younger officers, for the most part, even if simply through media associations, have grown up in a global culture. Like the rest of us, they too have all the prejudices that abound in America, but they didn’t grow up as culturally isolated as someone like Kroll and his generation did. The older generation, arguably, has a much more visceral attachment to ideas of “us vs. them.” Despite being relatively young, all things considered, Kroll was brought up and trained through hard knocks, old-school tactics. He was trained by the type of Minneapolis cops who hung suspects over the side of the Franklin Ave. Bridge to “get them to talk.”

Professionally and culturally speaking, he’s an old man now, desperately attempting to hold on to dwindling power. The narrative of the transcript, while 20 years old, speaks to the skills that, again and again, he states are not to be critiqued if you are not police. These aggressive, highly racialized skills and tactics are what he maintains must be kept in place for “law and order” to remain intact. And yet, the world goes on telling Kroll and his counterparts otherwise. He’s but one in a contingent of state actors — whether they be a cop, a judge, a prosecutor, or a politician — who are desperately, hyper-aggressively fighting the push for a change within the collective drama.

The simplistic narrative, which is nonetheless true, is that these sorts of methods and attitudes are purely motivated by race. But identity is complex, and while time has allowed for race to be the underlying factor in Kroll’s identity, the complexities of position, class, and power are all within the mix as well. Without understanding that, we accept a pitched, binary battle which is unwinnable.

Within the long now, Kroll has been conned into believing his own authority, when, in fact, he’s simply a puppet for a higher class of power that finds his attitudes, and as he states, his “role,” contemptuous and crass, but necessary. Kroll, despite his attitude and his access to an arsenal, is digging ditches for someone else’s benefit. When he becomes too embarrassing — and in turn ineffective — for those he does his job for, he’ll get tossed in that ditch along with the same people he currently attempts to control.

So, why publish something about this transcript now? Because this story always remains in the present through the actions of actors like Kroll, who assume the role of mechanized object to the same degree to which they force objecthood upon others for the benefit of those out of sight but in power. Kroll isn’t in power, he is powered — a mindless piece within a machine, fashioned to complete a task and yet certain, nevertheless that his actions equal cognition. Kroll only thinks he knows why he does what he does.

More pragmatically speaking, I’m concerned enough to act now for immediate and presently practical reasons. With some of the highest racial disparities in the nation, Hennepin and Ramsey counties are set to jointly spend $18 million dollars on a new juvenile jail facility. These new jails cells for kids, as statistics have shown, will mainly house children of color and serve no purpose other than funneling them into the system which profits off of their continued incarceration. The same sorts of systemic trajectories can be seen in the interaction between Kroll and 14-year-old Otis.

We can do better than to allow “old” stories, such as the one told in “Sgt. Kroll Goes to the Office,” to be the only narratives we are allowed to act out. There are new stories to be told. But why aren’t we telling them?

Throughout Minneapolis, there have been countless incidents of abusive police behavior over the last 20 years. And yet we mostly encounter predictable, cut and dried, official accounts of this egregiousness. Kroll’s actions, in particular, even prior to his representing the MPD rank and file, filled copious such reports, both official and journalistic. But why has so little stuck? With this effort, we thought, why not turn the telling of those tales on their heads? I am not an activist. I am not here to create solutions, build new hierarchies, or manifest new alliances.

As an artist, my job — and I see this as a productive position within the public sphere — is to disrupt. I take things apart so that they can be looked at in new ways. There are countless others who are qualified to reassemble. Inasmuch, under these circumstances, artists are afforded opportunities that activists lack. Why not do something different so that our present situation can be seen differently, in a new light?

So, why choose the form we did, in the end? No matter the real merit of comic books and their artistry, they arise out of a tradition of pulp and carry the aftereffects of being trash. When you have a story of one person in power treating another like garbage, why not make the medium fit the message?

With that said, the comic is not the work, in and of itself. The effects, questions, and unfolding narrative energized by the publication of the comic is the work. From the comic’s tactical distribution, to meeting with Kroll, to whatever else comes down the track — that’s the work. The comic is a means not an end. It is an action that materializes a public around it. And once that public begins to materialize, authorship is slowly forfeited, the actors expand and vary, and new roles are created.

ssWho are the other artists involved?

sgAnswering this question fits neatly into my closing remarks from the last. There were many artists who provided their skills in illustrating the story of Kroll and Otis. With the assistance of publisher and editor of Uncivilized Books, Tom Kaczynski, we assembled the following group: Tom Kaczynski, Eric Johnson, Clara Jetsmark, Peter Wartman, Lupi McGinty, Kurt Austin, David Bayless, Derek Maxwell. Fiona Avocado. Coryn Lanasa, Christian Moser, Jenny Schmid, Lilli Richards, Will Dinski, Ryan Dow, Brett Von Schlosser, Jordan Shiveley, Zak Sally.

We can do better than to allow “old” stories, such as the one told in “Sgt. Kroll Goes to the Office,” to be the only narratives we are allowed to act out. There are new stories to be told. But why aren’t we telling them?

But that list keeps expanding, and it is within that expansion that the work takes form. What I have been amazed at is how the utopian ideals of the work — envisioning your loftiest goals and collectively setting foot out in that direction — are becoming less dreamy the more steps we take towards the horizon. While I doubt we’ll reach that point — because you cannot, in fact, actually arrive at a horizon — what we’ve found along the way is the artistry of others getting involved by way of seeing the usefulness of (un)disciplining themselves from what they feel their professional or public roles are, disrupting what they find to be “normal.” Normal, in this case, is deadly. Those other temporary artists who have come out of the woodwork are inspiring. Seeing people believe in the merit of creating space for questions is energizing and useful for us all. The work goes on, and becomes stronger, precisely because I am losing control of its trajectory. A terrain is being formed. The social landscape, which was the kernel of the comic at its beginning, is expanding, and expanding far more rapidly and anarchically, than I would have ever imagined this quickly. We have to declare all power to the imagination if we are to disrupt this extreme level of systemic production and its violent effects.

ssWhat have been the repercussions of the comic’s release?

sgAs I’ve mentioned, the level of interest in this action has been overwhelming. But I don’t mean that purely from the standpoint of appreciation, as if the comic were an object instead of what it was meant to be — an action. So, to speak to its movement, I’m particularly impressed and appreciative of how people have received it.

Our initial distribution had me hand-delivering copies to all the city council members and the mayor, followed by a deliberate push on social media. I wanted to see, in this manner, how things would then move through the system. I was, within a day, in contact with one-third of the city council. In just a matter of a few days, word of the comic got back to Kroll, to the degree that he, personally, arrived at the shop and, avoiding any interaction with the person who was minding Beyond Repair at the time, grabbed a stack of copies and split. I was sad to have missed him, as I sincerely had wanted to talk with him about the comic. And so, I called the Police Federation, told him as much, and also invited him to come down to Beyond Repair for a book signing. He declined the invitation, but accepted the opportunity to speak. He offered for us to meet at the Federation offices, but seeing as some city council members had already offered space for us to speak on the off chance that Kroll did want to talk, I suggested we meet at City Hall.

What has followed, though, is where things have gotten interesting. More documents have surfaced; more voices who feel they have a stake in the matter offering to help, and take part, coming into the fold both locally and nationally; we’re hearing from officers who have worked with Kroll who feel that his tactics, and the tactics of officers with a similar demeanor, put cops — and citizens — at risk, who are in turn offering accounts of Kroll, his past, and his associations.

So much has risen to the surface and become clear. It’s almost as if the comic allowed individuals, for a moment, to exhale and breath deeply with the realization that something as simple as a comic book can energize and mobilize people so effortlessly. Maybe you don’t need thousands of people in the streets? Maybe one deft swipe of a pen and some fancy footwork will do the trick? It begs the question: what else haven’t we been doing? I’m excited to see what others might begin to do.

ssWhat’s next?

sgWith all the new details and new relationships materializing around other incidents involving Kroll which, as the comic has done, point to the systemic imbalances and violence that we allow to continue, the sky’s the limit.

Furthermore, those new details are up for grabs. Anyone with a good idea can run with them. Why in the world does it, or should it, be me or those I’ve been collaborating with? My hope is that that loss of authorship can be liberating in a variety of ways.

First and foremost, though, for myself and others I’m working with, is a desire to continue opening up spaces and mechanisms for questioning around these concerns and histories. Red76 has an installation, Yes, and…, opening at the MIA in November which will serve as a public platform to continue these discussions, bring to light these evolving histories, and consider the spaces which exist in-between what we consider the alternatives presented to us — what lies between “law and order” and “anarchy and chaos.” The fact that the board, museum donors, and audience who primarily attend MIA constitute the class that Kroll works for, and whose power tactically allows him to maintain his status and execute his violence, makes the siting of these questions all the more appealing to me.

A second, expanded printing of “Sgt. Kroll Goes to the Office” has been suggested, and there’s been talk of a serialized animation series based on Internal Affairs documents, first-hand accounts, and recollections, all relating to Kroll’s life and times as a character within the continuing saga of “the war on drugs” in Minneapolis. Lots of others play bit parts. Who knows where that will lead?

In the end, I don’t see any of this as adversarial. It’s been an educational experience, albeit a highly volatile one. Though that’s been my experience with education and institutions for my entire life. Why stop now?

Related links and information: If you can’t stop by Beyond Repair to pick up a hard copy of the comic, “Sgt Kroll Goes to the Office,” for yourself, you can read it in full online. Find more about Red76 and Beyond Repair via their respective websites, www.thisisbeyondrepair.com and www.red76.com.