Art, Class, and Desire

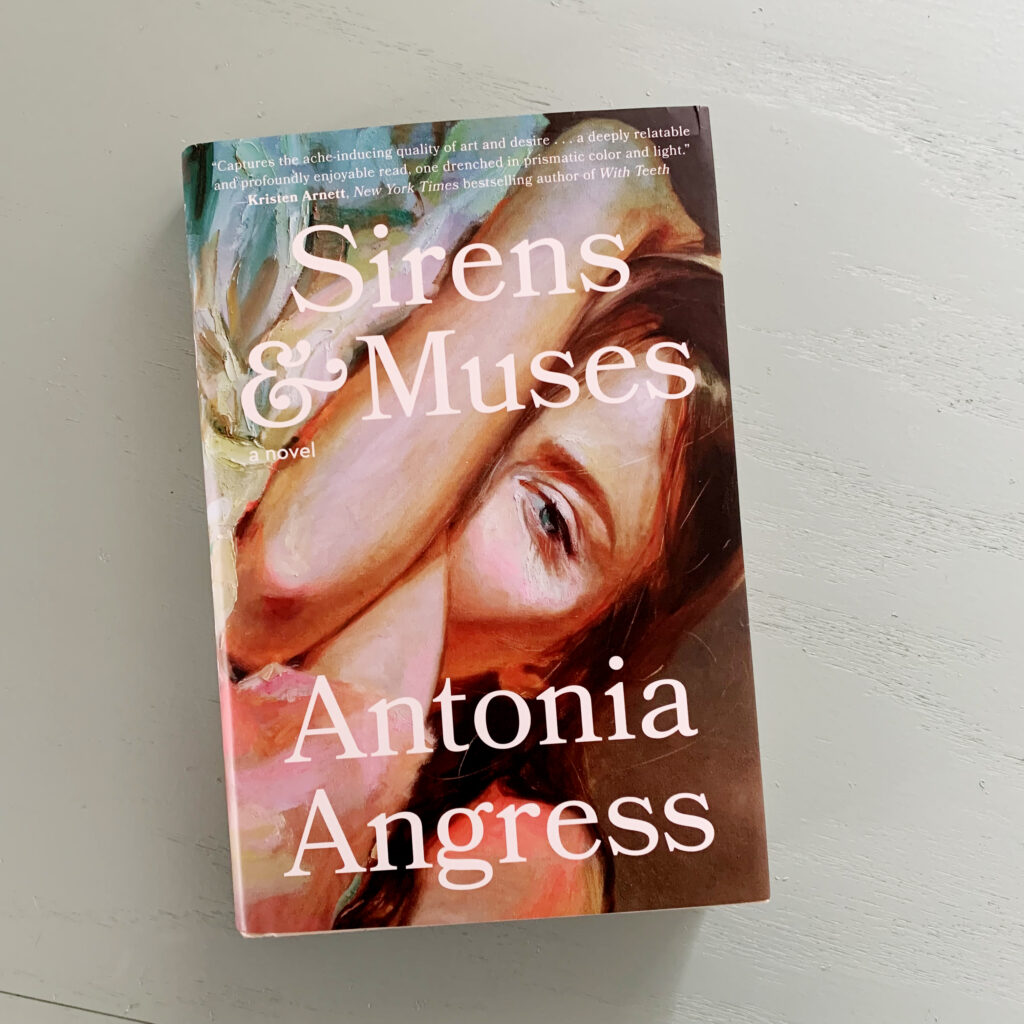

A conversation with Antonia Angress on her novel Sirens & Muses, competition in the art world, the impact of Occupy, and cultivating a creative career outside the coasts

Every once in a while, you come across a work that you really connect with. Recently, for me, that work was the novel Sirens & Muses by Antonia Angress. Set at an elite East Coast art school in the not-so-distant, but also shockingly far away, past of the Occupy Wall Street days, it follows the lives of four artists as they attempt to “make it” in the real world.

Granted, I didn’t go to an elite East Coast art school, and Occupy Wall Street kind of blew past me in the middle of Wisconsin, where I did attend college. But I’ve done my fair amount of struggling as an artist out in the real world, much like the characters in the book, who fight to find and stay on a path that combines their love of art with the demands of capitalism, even with the relative amount of privilege they each come from.

Throughout the book, characters wrestle to have their artistic voices heard, make a living in cutthroat New York, and stay true to themselves while trying to give their art value. Age seems not to matter in terms of strife. Wiser and more established artists lose themselves, get fired, and go to work as glorified nannies. Younger artists either grapple with finding their footing or become short-lived, “trendy” artists in the eyes of collectors.

Because of the small size of the art world, everyone seems to kind of, sort of know each other in some way, or knew each other in the past and have crossed paths again. It creates a web of rivalry that’s impossible to escape, and makes for fragile and fraught relationships that often seem more rooted in convenience than actual connection.

The exception is an affair between Karina, a cold and distant yet wildly talented prodigy whose flippant approach to relationships baffles everyone she meets, and Louisa, a sweet and timid artist from Louisiana who just wants to fit in somehow in the ruthless New York art scene. Their romance enhances the intensity of the art school setting, throwing me back to a time when the whole art thing still felt romantic to me, back before I had to make a living for myself.

Every character seemed to remind me of someone I knew, from Karina (totally knew someone like her at school), to a disgruntled professor named Rob (yep, knew him, too), to a hot jerk named Preston who treats life like it’s a giant prank (oh yeah, I know a couple of Prestons).

I read all the time, but very rarely do I find a book that’s relatable to me like this one was. It was the kind of book I could throw at people and say, “See, look how hard it is to be an artist!” and use it to validate the challenges I’ve felt ever since leaving school. I felt at home in its pages. I guess I loved it most because it made me feel like myself and every artist I’ve known wasn’t just floating out there without anyone noticing us.

After I was done reading, I felt like I had more questions for Antonia, and wanted to connect with her to find out how she so successfully captured the art world and all the beauty and discord that comes with it.

RACHELE KRIVICHIFirst, I really wanted to know why you set the book during the Occupy Wall Street movement. It’s unique to set a book during a time only ten years in the past.

ANTONIA ANGRESSI started writing this book ten years ago, in my early twenties, and was just out of college. I wrote the very first words of it in 2013—so, not that far removed from 2011. It feels like a long time ago now. I’ve had some Gen. Z readers call it “historical fiction.”

RK*Gasps audibly*

AAThere was a really practical reason for setting it during that time—I wanted to write a campus novel and it’s set from 2009-2013, during the same time I was in college. I didn’t want to set it during the 80s or 90s because I didn’t know the cultural zeitgeist of that time.

Also, I don’t outline my drafts, I just discover them as I go. As I wrote, the theme of capitalism started to emerge, and so the backdrop of Occupy started to make sense, and at that point I just set it during that time. Occupy happened when I was a junior in college, and it felt really all-encompassing. It felt like a catalyst for change. I think things didn’t really pan out the way people in my generation hoped they would, but it moved some things to the left in tangible ways. I remember feeling excited that things were going to change.

RKI guess I had never thought about Occupy in the context of the art world before, and I’m not sure why. How do you think Occupy affected artists in this book? How do you think it affected artists in the long run—if at all?

AAOnce I started doing research into the Occupy movement as I was writing the book, I discovered there was this whole offshoot of Occupy that was directly centering the art world. A lot of it revolved around the winner-takes-all economic system within the art world, where a tiny handful of mostly male artists were reaping 99% of the money and there’s very little left to go around for the vast majority of working artists. There’s no universal basic income or widely available sources of artist income, which leaves most artists fighting over crumbs.

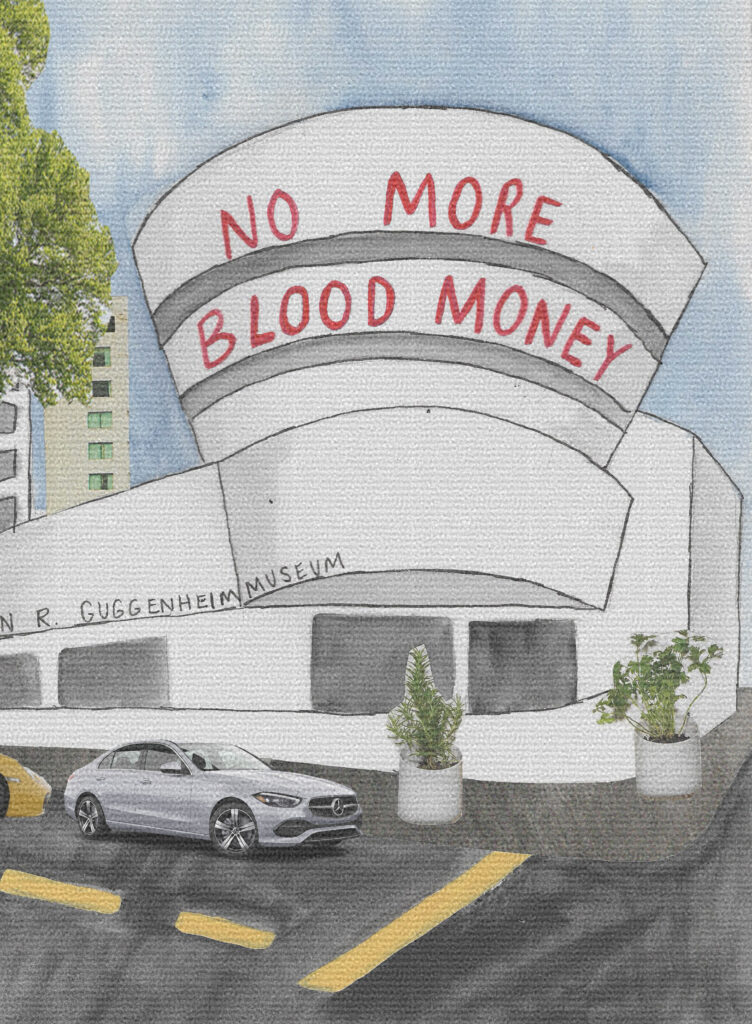

A lot of the activism in the Occupy Museums space has gained traction in the long run, for example, exposing that museums receive really dirty money to fund themselves. I recently watched the documentary about Nan Goldin, who tackles people like the Sacklers, exposing museums for taking blood money and letting this family clean its hands through art. The Occupy Museums movement was sort of the seed of that. In a lot of ways it was pointing at the ways in which the ruling class uses art and philanthropy to whitewash the sources of their wealth.

RKIt’s interesting because I was just researching and thinking about investing some of my money in art through a firm called Masterworks and thinking that was a “cleaner” place to put my money. But now I’m not so sure.

AAI did a lot of research about how rich people buy art. For some of them there is a love of art, but since the 80s, when the art market exploded, it’s definitely become like a stock pick. They invest in these up-and-coming artists, and then when it’s time, they “flip” the art like you would flip a house. There are art investors who can tell you where to invest.

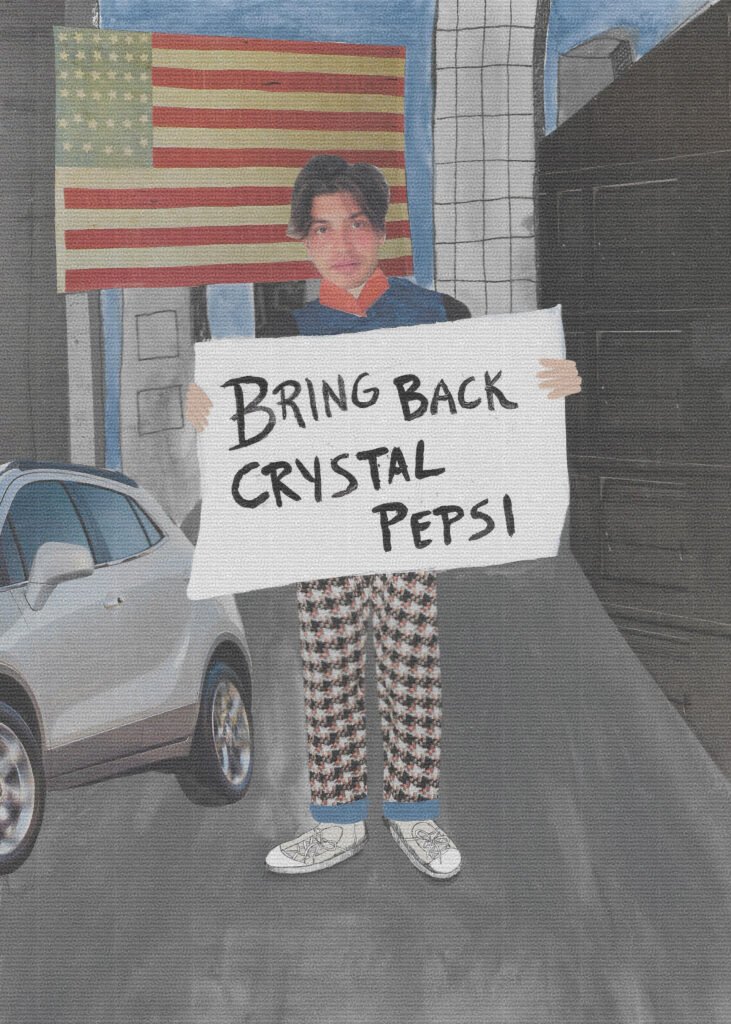

RKTalk about this quote referring to the Occupy movement: “I don’t know. I hope it can find a way to move forward. It’s hard when a movement doesn’t have a clear set of goals.”

AAWell, that was one of the big criticisms of the movement—that it was leaderless and there were no people who were strategizing about what the next steps were. It had a lot of very worthy goals regarding debt forgiveness and income inequality and reforming our financial systems, but not a lot of solutions for enacting those goals. If you look at the photographic evidence of Occupy (I used real slogans from real signs in the book), some of them are very poignant and very worthy goals regarding inequality and the way our financial system screws over the middle class, but a lot of the demands were just ridiculous (for example, a real sign: Bring Back Crystal Pepsi). So, the movement could kind of be co-opted for whatever purpose.

A lot of the analyses I’ve read blame that amorphousness for the movement fizzling, but I am actually of the opinion that Occupy did have a lasting legacy on our political discourse. For example, the conversation about student debt and whether or not we should forgive it—I think a lot of that rhetoric can be traced back to Occupy. Also, I’ve seen a lot more mainstream conversation about universal basic income. Not a lot of people were talking about that back in 2012, and now there are some cities that have put that in place.

RKYeah, I see a lot of criticism of movements all the time, even of the ones that are happening today like Black Lives Matter and various climate movements. But my thought is always that you have to show up even if you don’t think it’s going to do anything, because if you don’t show up then there is no message. The squeaky wheel gets the grease.

AAYeah, change might not happen overnight, but a decade down the line you might look back and say it did make a difference. ACT UP, another movement I talk about in the book, accomplished a whole lot. You can’t argue away that the organizers in that group got AIDS drugs on the market way faster than they would have been available.

RKChanging gears a little here, there’s a kind of sense of apathy among some of the artists—particularly Rob, a professor at the prestigious art school where the book is set. Does that apathy come from the time the book is set or do you artists are generally apathetic?

AAI think he’s apathetic at the point in his life in which it is set. I think it’s hard to be an artist, especially a not super successful one, just one who achieves a small amount of success and then is unable to really build on that. I think one of the dynamics that is happening in the book between Robert and Preston (his student) is this generational disconnect. I can relate to it now that there’s a whole generation below me that thinks about the world differently than I think. I can really appreciate what that’s like to feel older and feel less relevant, and have clashes of personality and ideals with the younger generation and to deal with that.

RKI really loved this passage, which I’ll condense here:

“Do you have any advice?”

“For what?”

“For being an artist? Out here, in the real world?”

“Don’t. I know that sounds terrible, but if there’s anything else you’re good at, do that instead.”

I was wondering if you could speak more on this quote.

AAThat’s not advice anyone has given me directly. Those are definitely things I have felt and thought before. I think it’s because pursuing any kind of creative career is really, really, really hard. Even when you’ve achieved something (like publishing a book, in my case), nothing is easier. I think opportunities open up when you’ve achieved them, but that’s it. It’s always going to be this uphill battle. It can be really discouraging and depressing and there are definitely moments when I’m like, “Why the hell am I doing this?” If you choose to try and forge a creative career, you have to do it for reasons other than conventional markers of success. You have to really love it for its own sake, regardless of how it’s received.

rKDid you have any experience in the art world before writing this book? You write about it so seamlessly.

AAI am not an artist, but I’ve had a lot of experience in the art world. My mom is an artist and she always put her creative practice at the center of her life. I come from a family that really values art. I grew up with this idea that art is a serious thing, a totally valid thing to dedicate your life to. When I went to college, I met my now husband, who is a painter and an architectural designer, and I’ve observed his practice evolve up close—I’ve even appeared in his paintings. Also Brown, where I attended college, was right next to RISD. I used to work as a model for their students and I became really fascinated with them. It seemed like they were having this really intense experience and they were all in this pressure cooker and they were experimenting and trying to form their identities all at the same time. I thought that would be a really good setting for a novel.

RKI thought Karina was one of the most fascinating characters, for many reasons, but one thing that struck me was how she was so talented but said she was thinking about her art in terms of its resale value. It made me kind of sad, but I also understood the intelligence of that. Do you think that’s what art is reduced to in capitalism, or was that just because she came from a wealthy background and had art collector parents?

AAI think that’s part of it, that she grew up in a family that valued art as this object of beauty but also was very attuned to its economic value. It’s interesting to me because I think it’s very taboo in any kind of artistic environment to talk about how much money you would make off your art, because we don’t like money and art to touch. It doesn’t make any sense, because the art world runs on money.

I definitely understand how orienting your entire artistic practice around how much money you can make off it could very quickly lead to work that is totally pandering to whoever you’re selling to. But I also think this idea that only authentic art is created outside of the reality of capitalism isn’t possible or desirable in the world we live in now. It also ignores class. Any kind of creative endeavor takes time. Time is money. It’s a nonrenewable resource. I think that attitude that we don’t talk about money because it’s irrelevant shuts out poor and marginalized people and leads to a landscape where only privileged people get to make art. Karina feels honest to me in a way that a lot of artists are not.

RKThe competition between the characters is SO REAL to me, and also I think adds to the weariness of the characters. Like, how tiring it must be to be sleeping with and in love with the person you are also competing with. Do you think there’s any way around this in the art world, or will it always be incestuous because it’s so small?

AAI think it definitely is always going to be incestuous. I’m in the writing world, which is also tiny, and everyone knows each other. I find it to be helpful to be married to someone who is not in that world.

With Karina and Louisa’s characters I was exploring a very specific queer female relationship. One of the things I wanted to capture in this book was that both Karina and Louisa are explicitly bisexual women. The experience of being attracted to a man and to a woman are very different and I think it’s almost a cliche at this point. There is definitely an experience of being attracted to a woman that’s like, “I don’t know if I want you or if I want to be you.” So there’s this dynamic of attraction and jealousy and admiration that all kind of blend together in their relationship.

RKYou’ve lived in both Minneapolis and New York. How do you think the New York and Minneapolis art scenes differ?

AAI have strong opinions on this. I’m American, but I grew up in Costa Rica, so I am able to see a lot of things from the perspective of a non-American. One of the things that strikes me about the U.S. is that Americans are very provincial. Wherever people are from and where they live, they automatically think that place is better than everywhere else. I love Minneapolis, I own a house here, I’m not leaving—but I also see the pros and cons of other places in the country. There are a lot of regional differences in the U.S. for sure. But I think Americans put a lot of stock in being different from other Americans. So that’s just one point.

The other thing that strikes me is that art in America is very, very coastal, meaning a lot of what we consider art with a capital “A” is coming out of big cities like New York and Los Angeles. Often I see art that comes out of a place like New Orleans, for example, being called “regional” art. It drives me insane because all art is regional. All art comes from a place. I think there’s this sense of big coastal cities being these centers of art and culture and everywhere else being this kind of flyover country. Again, it comes down to class. Those are cities that are incredibly expensive to live in. The attitude that you can’t be a real artist if you don’t live in New York is really saying, “You don’t have the money to live in these places.” The thing about Minneapolis and becoming part of the literary community here and writing here is that the cultural, literary infrastructure has allowed me to build the kind of creative life that I want. We have the Minnesota State Arts Board grants, and that’s something that doesn’t exist in other places.

RKEach of the characters takes a really different path at the end. It’s not so much of a “happily ever after,” but more of them each taking the path that works best for them. How did you decide which direction each character would go? (Mild spoiler alert.)

AAThe directions all needed to feel true to the character, to not make a decision totally out of left field. A lot of my decisions on the ending had to do with—who are these people, how have they grown and evolved over the course of the book, what is the logical next step for the person? Another point I wanted to make was what I was saying before about there not being a right or wrong place to build a life as an artist, or no right or wrong way to do it.

RKI loved Louisa’s decision to leave New York and go back home to Louisiana. I thought it was cool.

AAI thought it was cool, too. I’ve definitely had experiences of people telling me to leave a place that is working for me and I’ve never understood it. You just have to live in the place that is best for you, and whichever way allows you to thrive.