Pedagogy and Propaganda: A Manifesto for Anti-Fascist Education

Against the rise of right-wing, anti-democratic education policy: a proposal for an education that dismantles hierarchies, invites multiple perspectives, and imagines a better world

Since 2017, headlines declaring the “return” of American fascism1 have proliferated in mainstream publications. Despite fascism being as American as America itself, its rise has accelerated in the 21st century as ultra right-wing political movements encourage white supremacist violence through bigoted, anti-democratic legislation and rhetoric. Culture wars seek to eradicate marginalized identities, which puts education on the front lines. The urgency that the threat of fascism presents informs the urgency with which we must act to counter it.

“IF YOU DON’T WANT TO TALK ABOUT CAPITALISM THEN YOU HAD BETTER KEEP QUIET ABOUT FASCISM”2

On August 5, 1938, addressing a crowd of hundreds in Minneapolis, Roy Zachary, the lieutenant of the pro-Nazi Silver Legion of America, called for his vigilantes to take up arms and raid the headquarters of the Local 544 Teamster Union. In attendance were a number of ultra-wealthy businessmen, who had four years earlier lost their stranglehold on labor in Minneapolis in the 1934 Teamster Strike. After public condemnation for supporting violent antisemitism, one of these businessmen, George K. Belden, responded that he was not antisemitic and only attended the rally out of curiosity: “I am in sympathy with getting rid of the racketeers, employers and employees, whatever they are.”3 The possibility of renewed labor exploitation promised by fascist politics was enough for Belden to ignore the violent bigotry of the Silver Shirts, which, more generally, is representative of the relationship between capitalism and fascism: in the words of J. T. Murphy, a contemporaneous British labor activist, “[Fascism] is Capitalism in its most desperate, violent form.”4

Evidence of this is as old as American colonization. In the first decades of the 17th century, plantation owners accumulated immense wealth through the exploitation of enslaved and indentured Europeans, Africans, and Indigenous peoples. Threatened by worker solidarity and a slew of uprisings, these proto-capitalist oligarchs redefined race based on a hierarchy of skin color that equated whiteness with godliness. Manipulated by authoritarian falsehoods, European laborers became the police force that maintained chattel slavery.5 Centuries later, the capitalist consortium known as the Citizens Alliance (of which George K. Belden was a founding member) hired thugs deputized by the Minneapolis Police Department to violently suppress the picketing laborers during the 1934 Teamster Strike.6 Divide and conquer: history rhymes as tactics 400 years in the making continue to exploit the many for the sake of the few.

On February 2, 2023, Congress passed Denouncing the Horrors of Socialism, a resolution which condemns socialism broadly and vaguely, promising that the United States will oppose any implementation of socialist policy. No resolution similarly condemning fascism has ever passed Congress; amendments adding anti-fascist language—and excluding US social policies such as Medicare, Social Security, and unemployment insurance, from the definition of socialism—were voted down.7 Without any real policy associated, this resolution, just like the invention of race 400 years ago, is pedagogical and propagandistic, language leveraged for maintaining hierarchical control through economic power and mass manipulation.

Propaganda within the English lexicon carries negative connotations. Historically, however, and in other languages, propaganda is a neutral term8 for describing information that promotes an agenda. Put another way, propaganda is information organized into a narrative by a perspective. Through this lens, it is hard to see any information—whether true or false—as non-propagandistic. Propaganda becomes indoctrination, and thus fulfills its negative connotation, when it seeks to deny alternative perspectives through falsehoods and erasures. The House of Representatives, as a body of individual capitalists, defines socialism in demonstratively misleading terms9 so that socialists are unable to do so themselves. Socialism, as a framework for an equitable distribution of profit generated by labor, as a political structure that gives more power to workers than to businesses, is dangerous to capitalism, but no definition of capitalism is dangerous to socialism. Likewise, defining fascism risks exposing its proximity to capitalism. But erasure need not be so direct: in 1940, a new consortium of anti-union business leaders founded the annual Aquatennial Festival with the explicit purpose of overshadowing and erasing a yearly picnic that commemorated the efforts and sacrifices of the Teamsters in 1934. Growing up in Minneapolis, I attended Aquatennial but never heard of the Teamster Strike.

Everywhere in America we are inundated by capitalist propaganda verging onto indoctrination. Every advertisement deploys psychological tactics for manipulating and monetizing our behavior. Efficiency is righteous; productivity measures success; hierarchy ensures performance. Schools—like most nonprofit and public institutions—have embraced these capitalist values: education becomes a commodity, parents become consumers, and students become a future workforce for generating shareholder profit. Funding schools with property taxes, defunding schools directly through budget cuts and indirectly through inflation, manufacturing failure through test-based assessments, replacing tenured professors with underpaid adjuncts, decreasing time for teacher preparation while increasing administrative duties, managing school workers through top-down hierarchy—these all facilitate capitalist indoctrination and authoritarian control. Why is the labor of a superintendent three times more valuable than that of a teacher, who in turn is considered more valuable than a maintenance worker or special education assistant? Why is “managing” staff more valued than “managing” students?

Capitalism becomes fascism when wealthy oligarchs leverage their political power to maintain hierarchical, anti-democratic control over the people, often forging allegiances directly with white supremacist groups or indirectly through tolerance of intolerance in the name of “free speech.” Capitalist indoctrination supports fascist indoctrination.

“WHO CONTROLS THE PAST CONTROLS THE FUTURE”10

Since 2020, school officials and board members who supported critical race theory have been driven from their positions by a fury of death threats.11 Emboldened by wannabe tyrants and capitalist oligarchs, these fascist operatives in the American populace act as pawns in the culture war, dividing the people so that the few retain control. The Tea Party and Birther movements, Pizzagate and QAnon, Donald Trump and his GOP have fed the culture war, but Ron DeSantis has escalated its indoctrination through tactical policies that target learning and education. He and his government have banned books, limited what teachers can say about race, gender, and history, targeted LGBTQIA+ individuals and communities, engaged in a hostile takeover of a progressive and public liberal arts college,12 and censured the AP African American Studies course,13 whitewashing the violent racism of US history.14

Access to information is political. Knowledge is political. Pedagogy, as the study and implementation of methodological frameworks for transmitting knowledge, is politics. Education is the structure by which pedagogy is implemented. Fascism understands this. Fox News understands this. Ron DeSantis understands this. When he misled migrants into boarding a plane for Martha’s Vineyard with promises of jobs and housing, he copied a tactic by White Citizens’ Councils who conned dozens of Black folks into giving up their lives and moving north with false advertisements of jobs and housing. Without access to this history, without knowledge of the socioeconomic conditions of Black folks under Jim Crow, DeSantis can repeat the atrocities of the past with little opposition in the present. Erasing this history and replacing it with false narratives that enslaved peoples “personally benefited” from slavery is not merely an attack on education, but an attempt to fully harness schools as tools of indoctrination.15 Ryan Helfenbein, communications director for Liberty University, admits this explicitly: “Education really is evangelism. If you don’t control education, you cannot control the future—Stalin knew that, Mao knew that, Hitler knew that. We have to get that back for conservative values.”16 Their goal, just like that of Mussolini and Hitler, is to restrict information so as to confine knowledge to a white supremacist, capitalist mythology. Within fascism, there can be only one perspective, and any perspective that challenges the one must be eradicated, a sentiment illustrated by Richard Corcoran, Florida Education Commissioner: “The war will be won in education. […] Education is our sword.”17

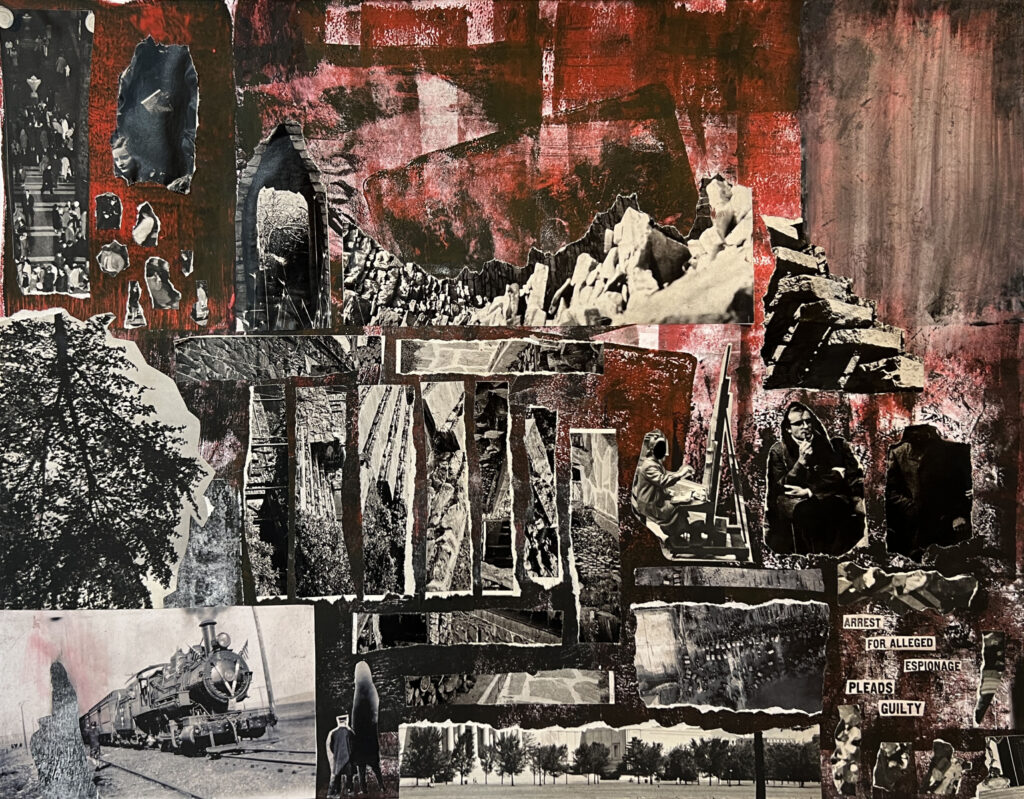

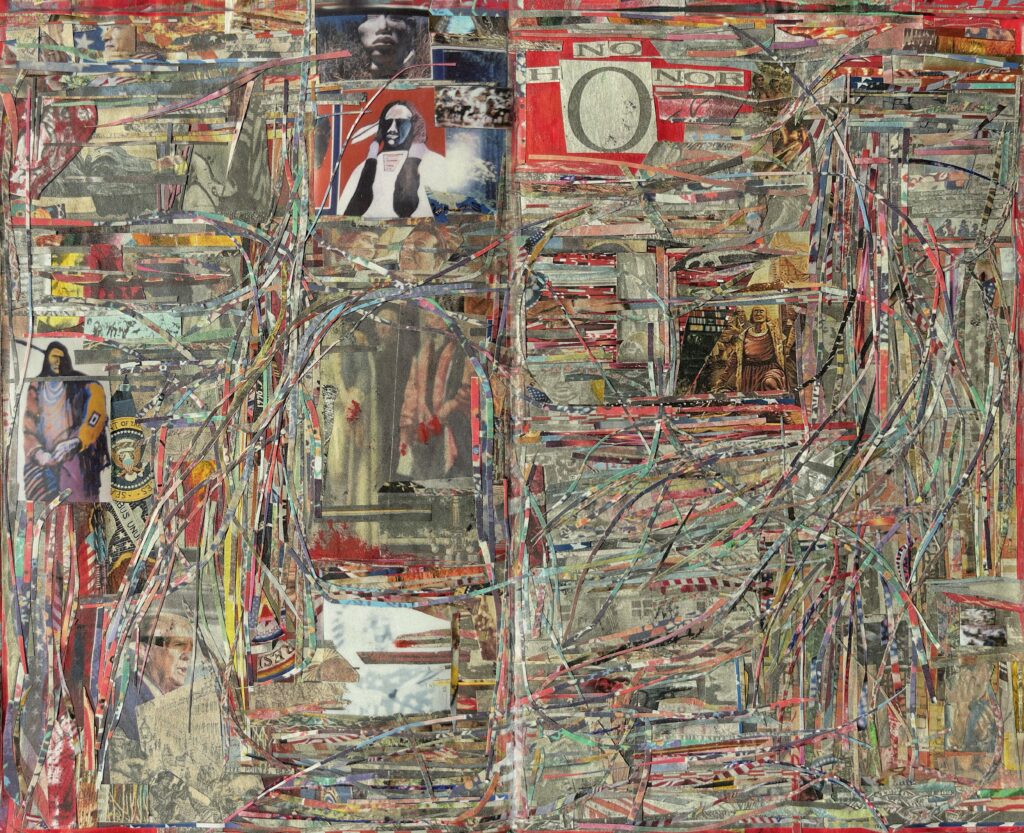

Similarly, the fascist Moms for Liberty group, which has spearheaded book banning in schools and libraries, quoted Hitler: “He alone who owns the youth gains the future,” and defended their use of the quote after public backlash. To “own” and to “gain” carry the language of colonialism and slavery, structures of hierarchy that fascism needs to maintain in order to keep power. Indoctrination begins in hierarchy; education becomes an exercise in ownership and control. Insofar as anti-fascism frames itself in opposition to fascism, we can begin to understand anti-fascist education through reversals: where fascist education demands hierarchy, anti-fascist education deconstructs it; where fascist education maintains and/or restores legacies of colonialism and imperialism, anti-fascist education decolonizes; where fascist education centers a single perspective—that of imperialist capitalism—anti-fascist education embraces a plurality of perspectives to cultivate a multitude of ways of knowing the world; where fascist education seeks to own the youth, anti-fascist education seeks to gift them the knowledge, skills, and confidence to reshape and reimagine a better community, a better world, a better politics.

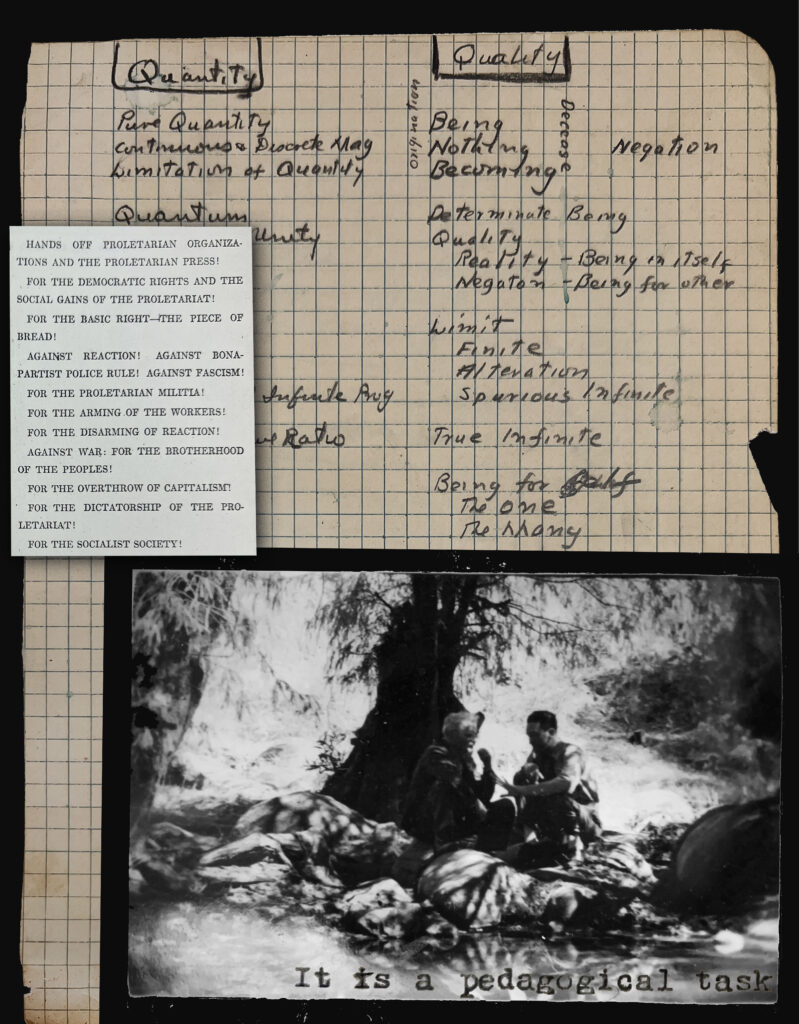

“IT IS A PEDAGOGICAL QUESTION, BUT IT IS A GOOD SCHOOL FOR THE COMRADES.”18

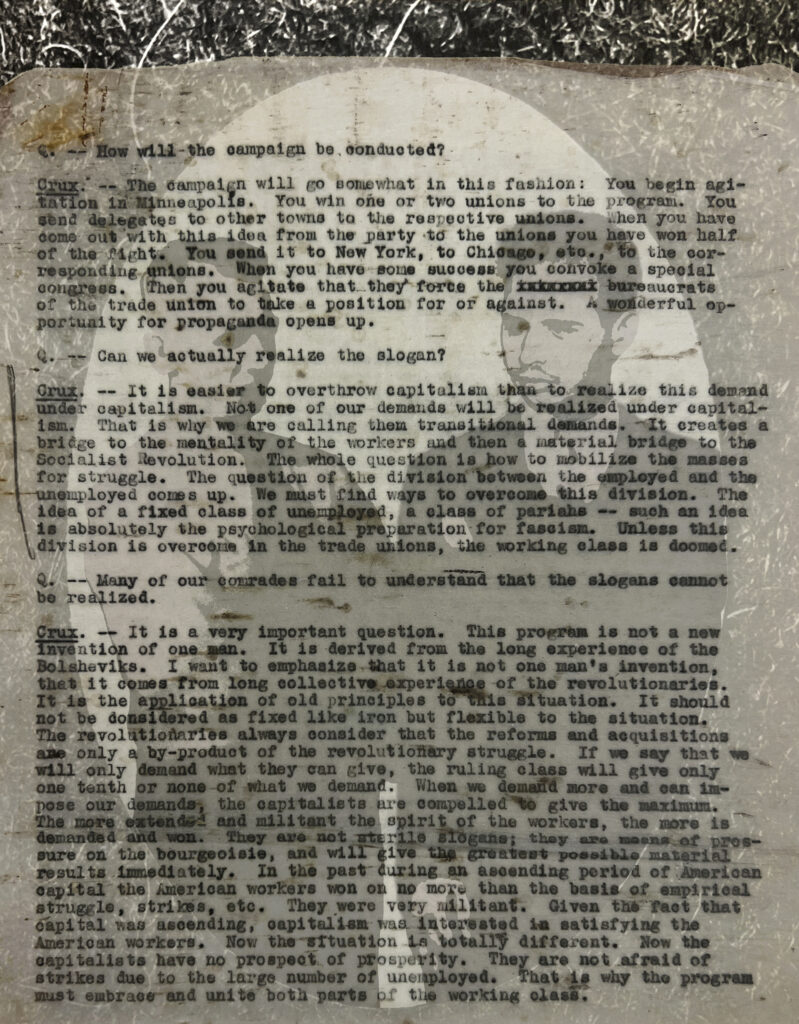

In 1938, as the dual threat of capitalist-fascists and American Nazis grew in Minnesota, Vincent Ray Dunne traveled to Mexico, reuniting with James Cannon and Max Shachtman, national labor leaders instrumental in the 1934 Teamster Strike, at Frida Kahlo’s Casa Azul to study anti-fascist organizing with exiled Leon Trotsky. In three transcripts of conversations, which read more like seminars, Trotsky takes on the role of professor collaboratively exploring questions of labor, history, organizing, and revolution with Dunne, Cannon, and Shachtman: “How is [a workers party] constructed?” “How would you motivate the slogan for workers’ militia?” “What name would you call such groups?” “How can you explain a revolutionary party?” “What influence can ‘prosperity,’ an economic rise of American capitalism in the next period, have upon our activity as based on the transitional program?”19 Each of the three conversations has its own theme and set of questions. The first conversation from April uses the particularities of the Minneapolis Local 544 to imagine the development of a national labor party and an anti-fascist militia. The second conversation from May 31, 1938, begins in the historical relationships between trade unions and political parties, before further considering the steps necessary to form a revolutionary party. The third conversation on July 20th, 1938—the fourth anniversary of Bloody Friday when police opened fire on Minneapolis strikers killing two and wounding 67—centers on how economic conditions will impact a united labor movement and its propaganda. In these conversations, questions frame collaborative discussions, generating knowledge collectively.

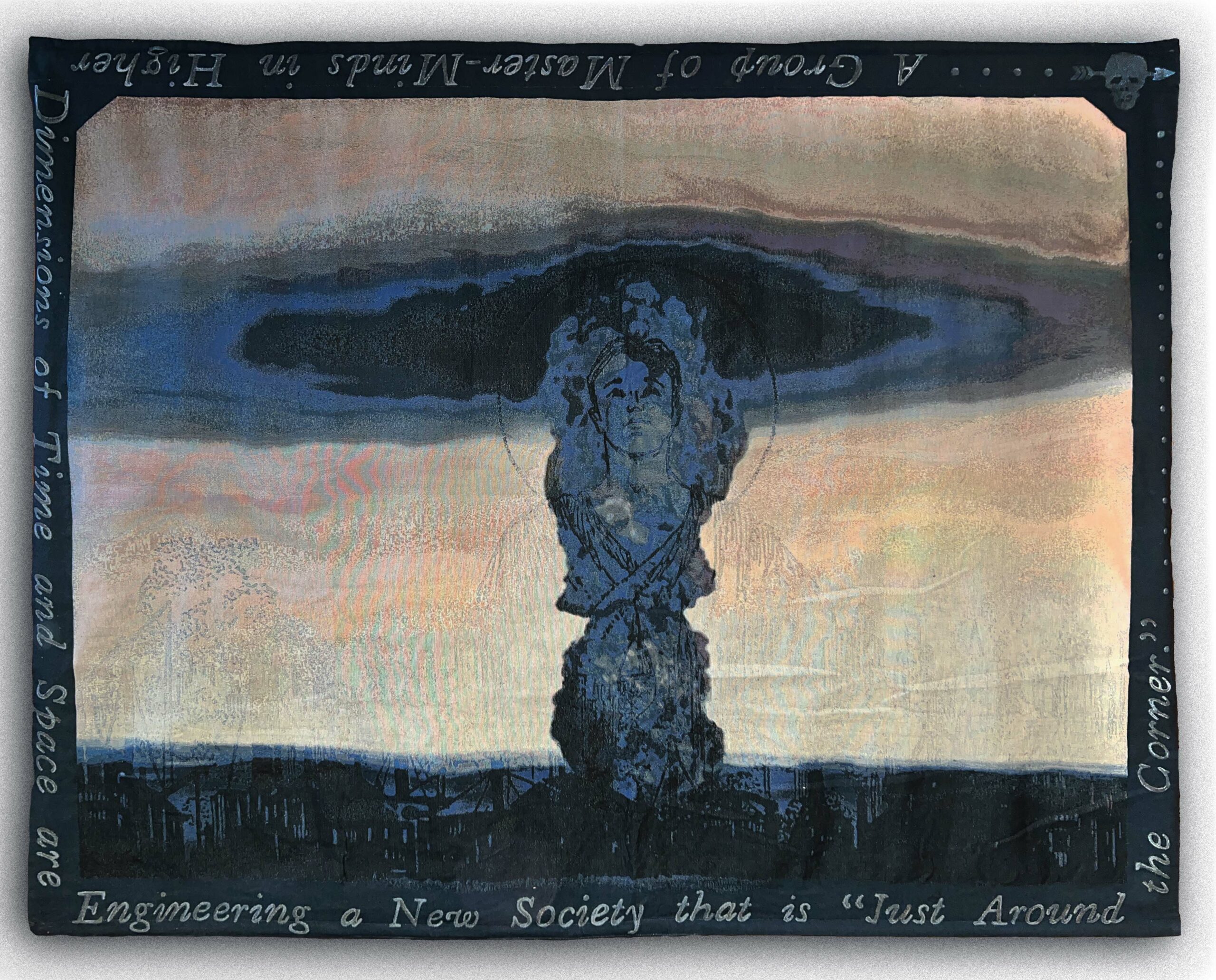

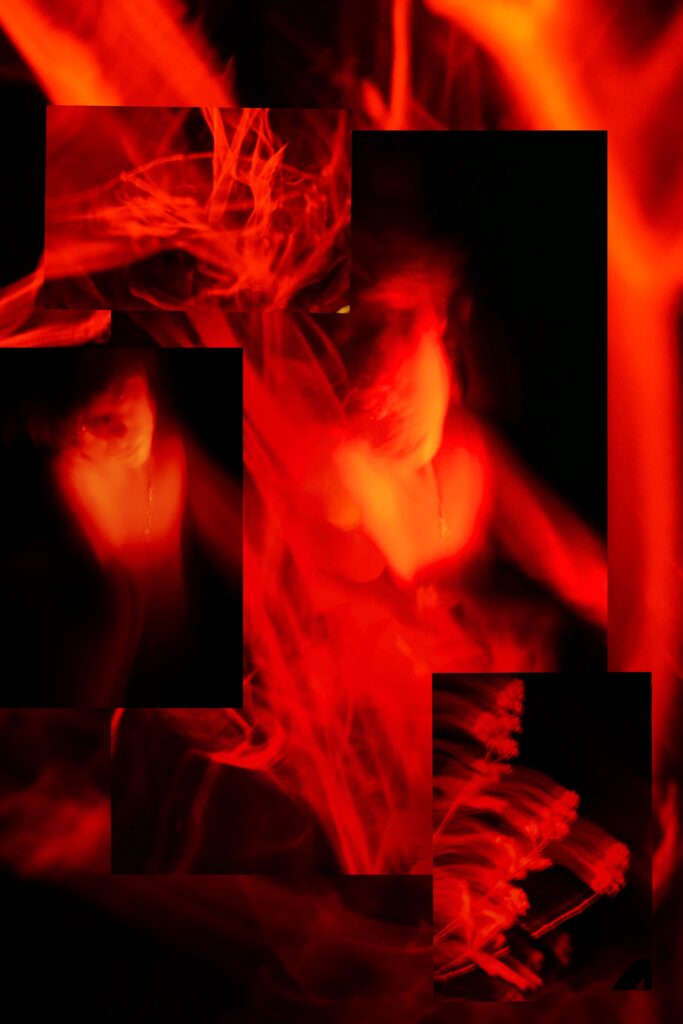

These months in Mexico have occupied my mind for the way they bring together history, political theory, labor organizing, and art. The home of artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera frame the conversation in aesthetics even though art is not directly mentioned. Rivera had already depicted Cannon, Shachtman, and especially Trotsky in numerous paintings, including the monumental, anti-capitalist Man at the Crossroads, and a silent film made in 1938 by Ivan C. F. Heisler shows Trotsky pacing back and forth in front of Rivera’s Communicating Vessels while dictating to a secretary. I imagine untranscribed moments at La Casa Azul filled with the contemplation of art. And indeed, between the second and third conversations, Trotsky wrote a letter to the Partisan Review which was published as an essay titled “Art and Politics in Our Epoch.” In it, Trotsky declares Rivera the greatest interpreter of the Fourth International, situating his work within historical and contemporary political theory. Rivera’s work, according to Trotsky, was evidence that “a progressive movement occurs in art,” and that “truly intellectual creation is incompatible with lies, hypocrisy and the spirit of conformity. Art can become a strong ally of revolution only insofar as it remains faithful to itself.”20 Art is a companion to labor organizing and to revolution, aesthetics a tool for combatting capitalism and fascism through utopian visions that scatter “the clouds of skepticism and of pessimism which cover the horizon of mankind.”21

Concurrently, 3000 miles northeast, Black Mountain College undertook a similar experiment in education that integrated art and labor into all aspects of the curriculum. Mornings consisted of lessons in literature, foreign languages, art, theater, music, biology, and math, among others, while in the afternoon students and faculty shared in the labor of maintaining the functional operations of their school and community. Farming, plumbing, heating, roads, paths, buildings—“not a token work at all, but real and necessary work that everyone shared, that had to be done.”22 This shared labor broke down hierarchies while strengthening the community. No one ranked above anyone else; everyone shared in the fruits of their labor. Students participated in the process of making major decisions for the school, while a consortium of faculty led the school in day-to-day operations. Black Mountain College prioritized community over the institution. No superintendents, no executive committees, no boards of trustees—structurally anti-hierarchical and therefore anti-fascist.

The utopian ideals that underpin both the Black Mountain College and that spring in Mexico with Trotsky, Cannon, Shachtman, Dunne, Rivera, and Kahlo establish a foundation for anti-fascist education. Through this dual lens, education broadly is a social and communal function. Implementing a pedagogy expresses social ideology in how it structures access to knowledge. In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paolo Freire offers a useful theoretical framework:

“Through dialogue, the teacher-of-the-students and the students-of-the-teacher cease to exist and a new term emerges: teacher-student with students-teachers. The teacher is no longer merely the-one-who-teaches, but one who is himself taught in dialogue with the students, who in turn while being taught also teach. They become jointly responsible for a process in which all grow. […] Here, no one teaches another, nor is anyone self taught. People teach each other, mediated by the world…”23

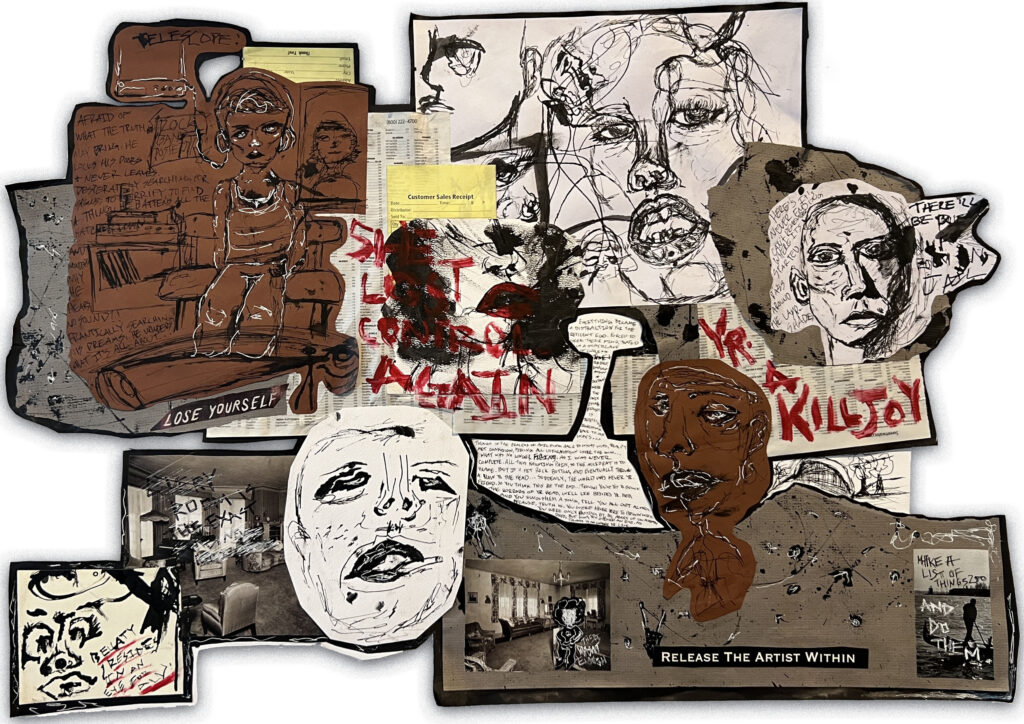

Freire penned his theory in the late 1960s, while almost exactly concurrently the Black Panther Party mandated anti-hierarchical, decolonial education “that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present-day society.”24 By 1973, the curriculum of Black Panther Liberation Schools included history, political theory, music, and “people’s art,” which was taught by Emory Douglas. With bold blocks of color, figures engaged in protest or other forms of social organizing, slogans inspiring militancy, solidarity, and resistance to white supremacy and American fascism, Douglas defined the aesthetics of the Black Panther Party, articulating the imagination of the revolution while teaching in images. Art was a tool of pedagogy and propaganda.

“RELATION IS LEARNING MORE AND MORE TO GO BEYOND JUDGEMENTS INTO THE UNEXPECTED DARK OF ART’S UPSURGINGS. ITS BEAUTY SPRINGS FROM THE STABLE AND THE UNSTABLE, FROM THE DEVIANCE OF MANY PARTICULAR POETICS AND THE CLAIRVOYANCE OF A RELATIONAL POETICS.”25

I see critique as the heart of art education. Rather than a space of criticism or authority, critique is a generative dialogue where teachers-students and students-teachers together mine an artwork for meaning, sharing perspectives and cultivating knowledge. Both making and viewing art begins in presence, being open to the world outside oneself. Every artwork and every interpretation of it presents the possibility for reimagining the world. Thus, the space of critique enables all those involved to explore the complex relationship between the individual and community, the self and the world. Critique has the capacity for modeling social reality.

This definition of critique is still utopian, and I know personally that I have often failed to fully implement the pedagogical theories for which I advocate in these paragraphs. Nonetheless, everything begins in striving. I share this essay-manifesto not as a manual for how to implement anti-fascist education—I am still learning what this means for me and my educational community—but rather as a call for all of us to think together through these essential aspects of education as it relates to our communities and politics. It is a call to arms against the deadly virulence of fascism as it shapes education for its own tyrannical ends. It is an indictment of the indoctrination that already defines education in America. It is a proposition that art is a tool with which an anti-fascist pedagogy can be realized.

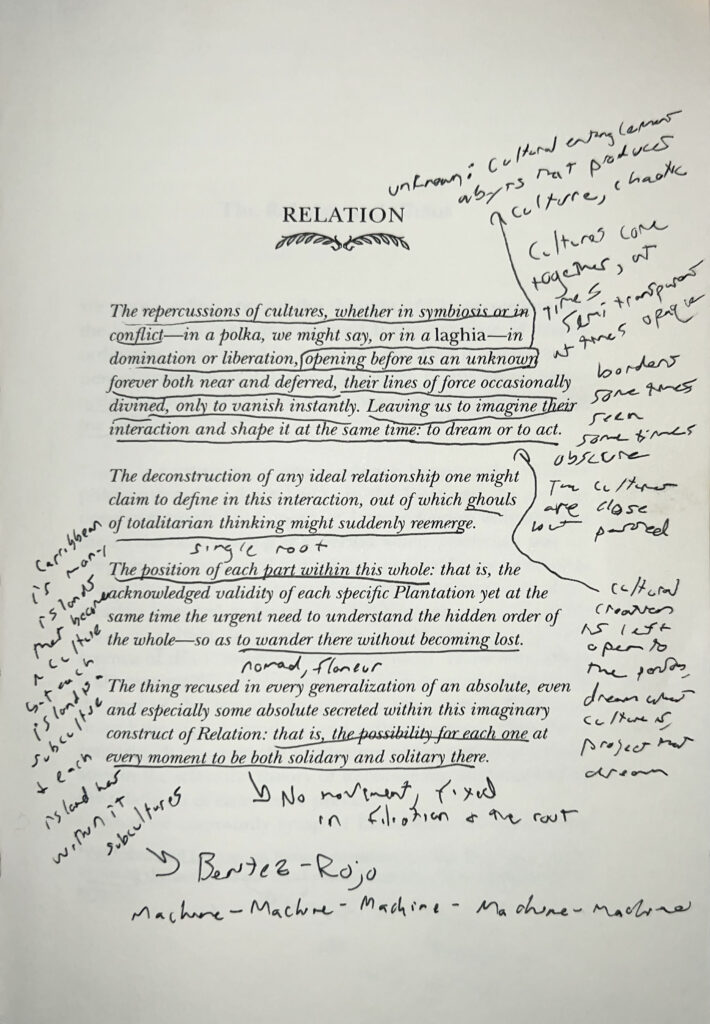

I have often turned to Poetics of Relation by Édouard Glissant in my exploration of a pedagogy for anti-fascism. While Glissant never defines education or pedagogy, his articulation of Relation entangles together history, colonialism, revolution, economics, and art, in much the same way as Black Mountain College and Trotsky’s school for the comrades. Relation is realized in rhizomatic horizontality that “opens onto the functioning complexity of the world.”26 Where fascism centers a singular perspective, Relation “makes every periphery into a center; furthermore it abolishes the very notion of center.”27 Where fascism feigns objectivity in its expression of authority and control, “Relation informs not simply what is relayed but also the relative and the related. Its always approximate truth is given in a narrative.” Where fascism transforms propaganda into indoctrination, Relation transforms propaganda into a poetics, which “aims for the space of difference—not exclusion but, rather, where difference is realized in going beyond.”28 Despite this oppositional formulation, Relation offers a poetics that could move anti-fascist education beyond opposition and into genesis. Relation engages history while renewing life—how can anti-fascist education do this as well?