River Bed

A dispatch from the protests against Line 3: on temporary beds, place and settlements, water and dreams, intimacy and resistance

“I didn’t come here to fall in love…”

That’s what they said as they were preparing to go.

“…I came here to stop a pipeline.”

*

Sitting on a dock suspended over dry land, a dock we built together in springtime, we admit to each other that we cannot stop a pipeline, but we are, after everything, falling in love.

*

We call it a riverbed, that space between the edges of water.

All the land a river flows over.

A constantly changing topography hidden by movements.

*

The river had just overflowed its banks when they arrived, widening the riverbed. A small group of us walked to meet the water, then spent hours hopping from one downed tree to another, rescuing boats that had come unhitched and other debris snagged against branches.

*

That night and for days after we pitched tents on narrow slivers of high ground across the river bottoms, temporary islands we gave temporary names:

Mud Sucking Blues Island.

Island of Lost Keys.

Only Sometimes Island.

We slept together on that ancient riverbed.

We slept inside that flood.

*

“You didn’t come here to fall in love, but that’s exactly why I’m here.”

I tried to explain the look in my eyes, which I’d just been told was like that spring flood, muddy and fast.

“I came here to fall in love with this place…to learn its language.”

*

In the water, watching the pipeline workers watching us trespass. Trespassing boundaries we refuse to acknowledge, since all borders imply the violence of their enforcement.

Feeling their eyes on our bare skin and the riverbed soft beneath our feet, we ask,

“Do you even know where you are?”

And,

“Do you know what you came here for?”

*

What brought you here?

Anger.

Responsibility.

A gut feeling.

A post on Facebook.

Urgency to protect what’s left.

What did you find?

A river rising and falling.

A movement winding and widening.

Living beings some know as relatives.

What found you?

River blanketed with ice.

Ice out, river open.

Mud season, everything is river.

Dry spell, river disappearing.

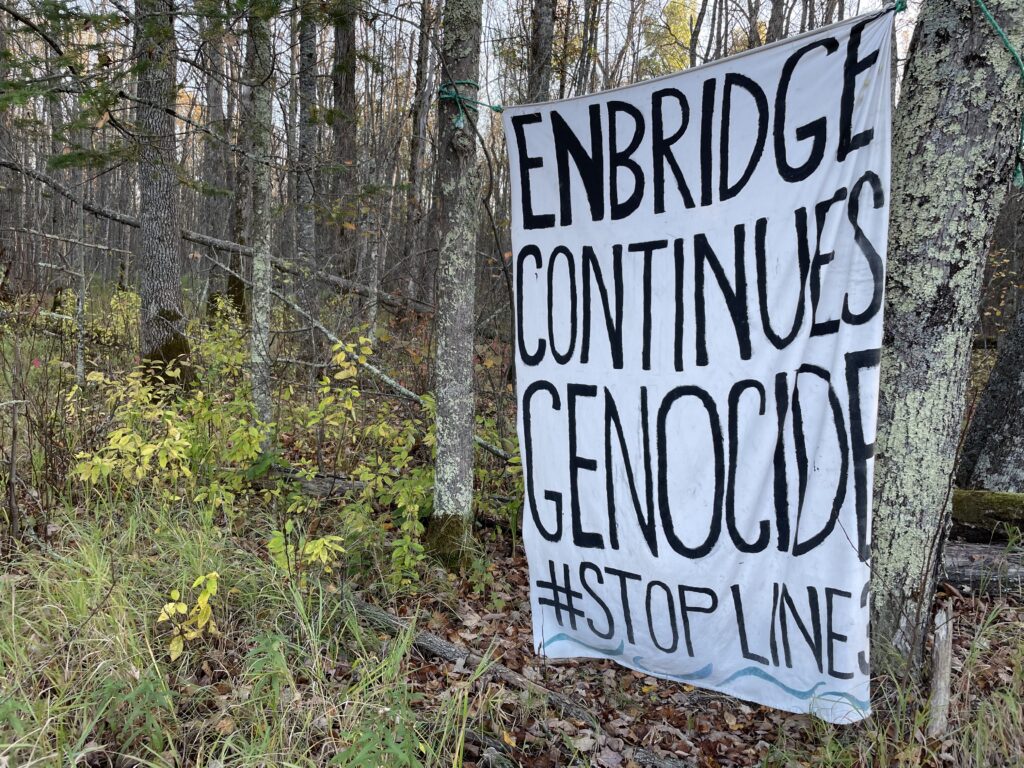

Spring flood on the Mississippi just south of Line 3 construction. Photo: Shanai Matteson.

View of Line 3 and Mississippi crossing after construction was completed. Photo: Shanai Matteson.

View across the river from treaty camp with lights from Line 3 private security. Photo: Shanai Matteson.

*

In just a few months the water had receded more than 10 feet, exposing the bottom of the river—narrowing the bed.

Mussels gasped in the heat of the sun.

Clay dried and cracked.

Arrowroot withered.

It was a drought they called historic, because saying something is historic sounds better than saying that it’s doomed.

*

Through it all, the pipeline company kept pumping water from the river and moving it in large tanker trucks. Using the river to drill through the river.

We were there to try to stop them, but we weren’t able to stop them.

The sound of trucks all day and night became part of our dreamscape.

*

At night, by the river, we gathered around the fire and told our stories.

We looked into each other’s eyes and wondered how we ever found each other in that darkness, and how much time we had left together, here?

During the day we gathered around the water, and watched as it changed.

The river was a bed to cool our bodies, to rest, to let loose our tears, to be held buoyant amid violence and chaos, to make commitments and to bare our souls.

*

Just out of view around a bend in the river:

Trees were cut down, trenches dug, pipe buried.

Out of view, but we could hear and feel it.

*

For a year police gathered.

People stood in defiance.

Some were kettled and arrested immediately,

others followed and harassed for months.

*

Before any of this happened, I’d had a dream about that landscape.

*

I dreamt of my grandmothers:

One of them in the garden on her family’s homestead, which was just down the road from where the pipeline crossed the Mississippi; the other on the shore of Lake Superior, which is where this pipeline ends.

Both seemed to be saying to me, “Touch this earth, feel this water.”

They seemed to be asking, “Where are you?”

*

The dream was about making a place together, but I didn’t know it then.

The dream was about falling in love with a place, and with people, knowing this meant being moved to join in a fight to protect them.

*

In the dream, there were people with me.

I’d been looking for them in darkness.

It wasn’t just about stopping a pipeline.

It was also about unsettling ourselves.

*

“To stop a pipeline, you have to find out where it begins.”

All year we searched inward, for any sign of that same greed, selfishness, or desire to consume and control.

*

We slept by the river on those nights when they were drilling.

I remember because it wasn’t really sleep, but a kind of waking dream.

I could feel the vibration of the drill in the ground beneath me, and in my body.

Some woke up angry and confused,

others went numb from the pain.

*

I was stuck somewhere in between.

*

One of those nights, police officers came in without turning on their flashlights.

It was so dark we could barely see them, but we could hear them walking around our camp—could see through the narrow openings in our tents the glint of their cell phone screens as they moved between the trees.

In that moment every muscle in my body seized up, as if my body was trying to close itself or fold me into a smaller being—one that could burrow into the muddy bottom.

*

I imagined them grabbing someone and pulling her away, or “accidentally” discharging a weapon into a tent where women slept.

That didn’t happen, but police took pictures and then left without saying a word.

*

A few nights later, when one of the people who was watching over our camp came around to check on us as we slept, I got startled and sat straight up in bed.

I was not awake, but not exactly asleep.

I was gasping for air, unable to breathe.

He stood outside my tent, shining in with a flashlight.

*

I’d been dreaming an underwater dream. It wasn’t unpleasant. The water was warm and soft. I clung to a friend’s body as they stood in the current, but woke to a panicked voice saying,

“It’s me! It’s just me! I’m sorry…I didn’t mean to scare you.”

*

Fear flows through us, and between, moving over our skin like that river over riverbed. These moments just dredge up memories from our deeps.

Memories of water and violence.

Memories of land and the violence of extraction.

Like studying core samples, we examine the layers. We try our best to hold onto each other in a pulling current.

*

It’s a shame we’ve confined sex to the bedroom, and made it seem like a singular act, for our pleasure alone.

That summer, we had sex in the riverbed, with our toes and heals digging into the mud.

We did it standing up in the water, and lying in the sun on the water’s temporary edge.

We made love facing the police, and outside the jail.

(Inside too.)

Sleeping on the courthouse lawn. Waiting for those we love to be released.

And we made love in the kitchen, nourishing each other. Reproducing a resistance. Hollering out to the woods and everyone in them that there was something to share.

*

We shared what we made.

*

After the pipeline went through, people started leaving.

It was hard to be in a place that had been violated like that, or to be with people who had given so much of themselves, and were now flooded with grief.

People we’d slept with.

People we loved.

*

Some stayed a little while longer.

We walked the paths we’d been making all summer with our movements, now covered in fallen leaves—and found evidence of our love and our heartbreak everywhere.

They said the oil had been turned on,

but we didn’t really believe it.

*

A helicopter flew over, monitoring the land from the air—confident they’d won.

We gave them the middle finger,

then made love on the bare ground.

*

View of the Mississippi during summer drought just downstream of Line 3 crossing. Photo: Shanai Matteson.

View of the Mississippi during summer drought just downstream of Line 3 crossing. Photo: Shanai Matteson.

“What do you think they will remember?”

They ask, stacking wood for the winter, though they don’t intend to stay.

“Who?”

Stacking wood for the winter, though they don’t know how to leave.

“The workers. Your children… All the ones who are still here.”

*

I hope whoever and wherever they are, they will remember at least this:

We made love.

We never fell.

To learn more about the Line 3 pipeline and Indigenous-led movement to stop it, visit stopline3.org and for updates on current events visit resistline3.org media collective.