Reliquarium: On Alexa Horochowski’s Under the Sea-Wind

On relics of the relationship between humans and the sea: speculative wonders and memory amidst waves, sand, wind, bronze, and concrete

You walk into the room as if into the sentence:

“Both water and sand were the color of steel overlaid with the sheen of silver, so that it was hard to say where water ended and land began,”1 writes Rachel Carson in the beginning of Under the Sea-Wind, the book Alexa Horochowski’s show at Dreamsong is named after.

And it is from this meeting-and-merging threshold potency that Alexa’s works emerge.

Under the Sea-Wind features projected videowork, sound, and an array of objects, castings and sculpture, that carry the loneliness and naked beauty of relics.

Relic–what survives.

Sea-wind–what puffs sails and lifts gulls and roils waves–is a threshold phenomenon, a merging of water and air and salt spray in a convergence of co-animate elemental forces.

Fishermen and poets cast their lines, a sculptor casts her objects.

“I was casting objects that represent flotsam and jetsam but was interested more in how they got there,”2 writes Alexa on her attraction to the role of wind in Carson’s work. It courses throughout Carson’s text as element and propulsion: “with the rising tide, a strong wind was blowing in from the sea and storm clouds ran before it. The green ranks of the marsh grasses swayed and their tips bent to touch the rising water.”3

“Inspired quite simply by her love of the mysterious and the wonderful,”4 Carson’s writing in her literary debut swoops and moves and shifts perspective in such a fluid way, as if to be carried by wind.

I hear Yoko Ono & The Plastic Ono Band singing the words of Christina Rosetti5:

Who has seen the wind?

Neither you nor I:

But when the trees bow down their heads,

The wind is passing by.6

Volitional air–agent invisible–zephyr gale squall gust.

Alexa Horochowski has been courting wind power in her work–see Vortex Drawings produced under the conditions of a manufactured whirlwind–and here, in Under the Sea-Wind, its mystery swells.

It carries something of the wild intensity and perpetuity of its presence in Patagonia, the place of Alexa’s childhood, and bears kinship with another invisible presence in this show through the speculative wonders herein–a supernatural imagination.

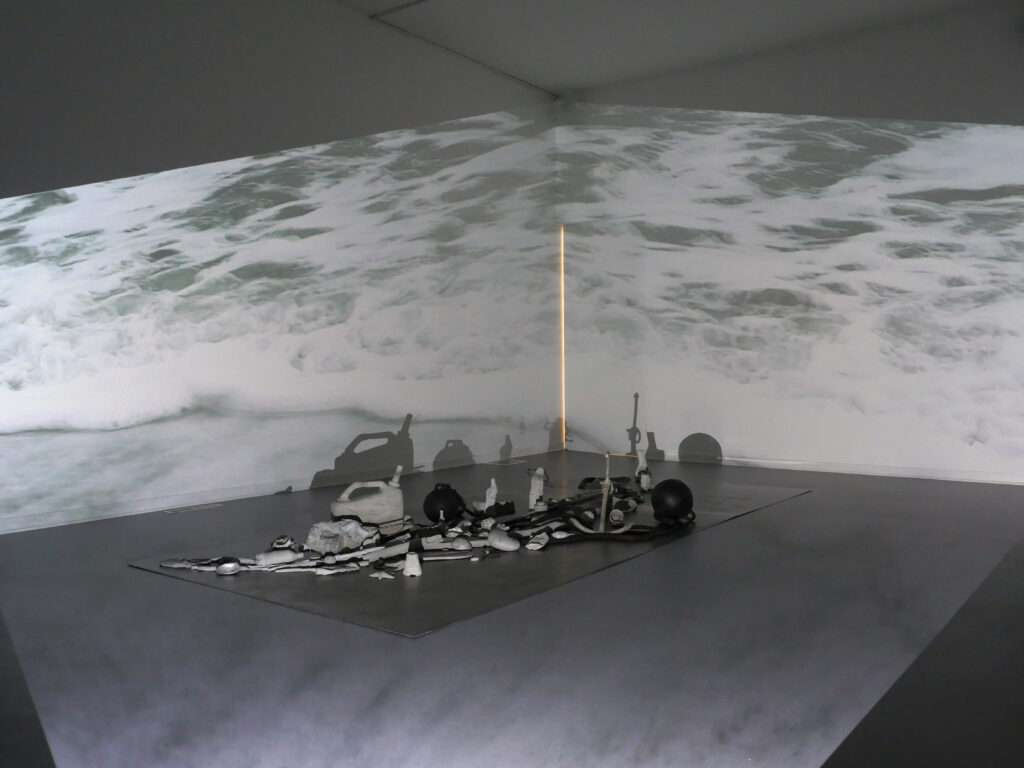

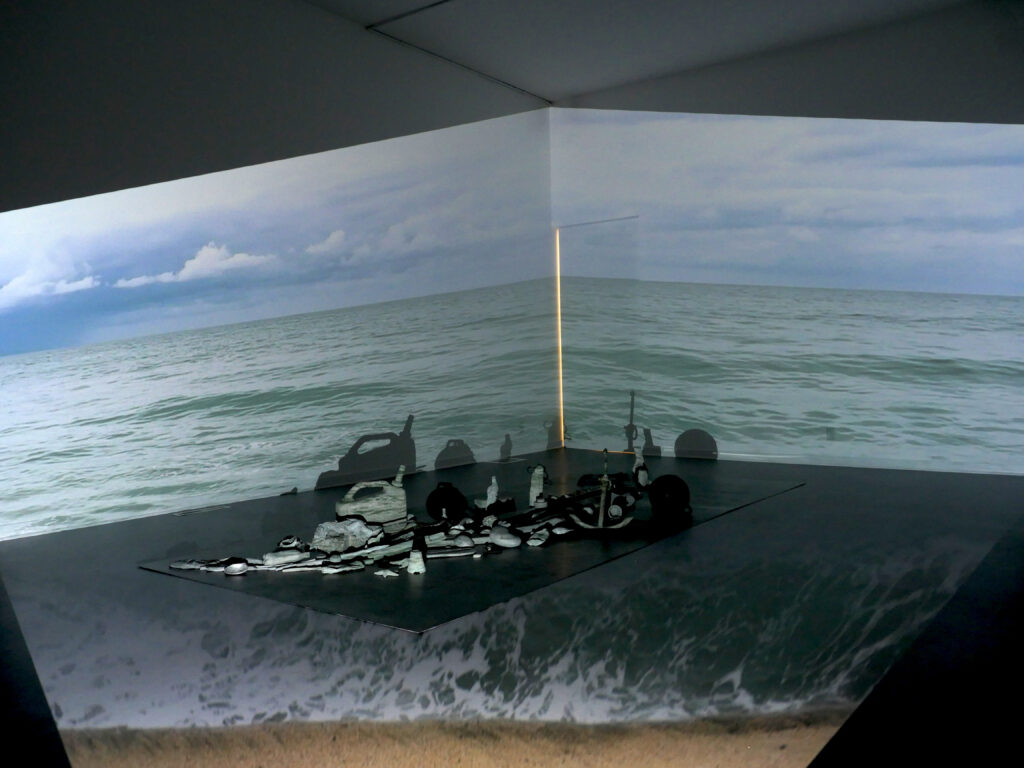

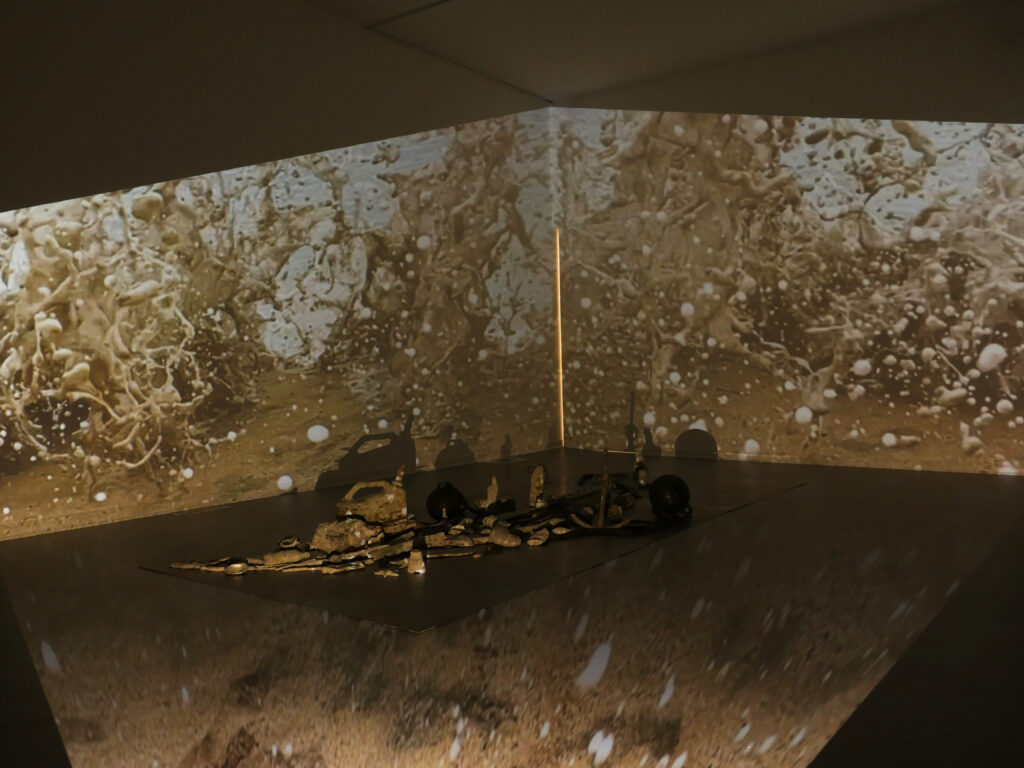

The First Room: Wrack Line

You walk into the room as if to the edge of the world.

A beach precisely, made gray and silver in the light of a full wall projection of foamy waves crashing on the gallery floor, and across an array of sea-spewed detritus.

A wrack line or wrack zone refers to what the sea gives to the beach at high tide, the material trace of its reach–”organic material (e.g. kelp, seagrass, driftwood) and other debris.”7

Note “other debris.”

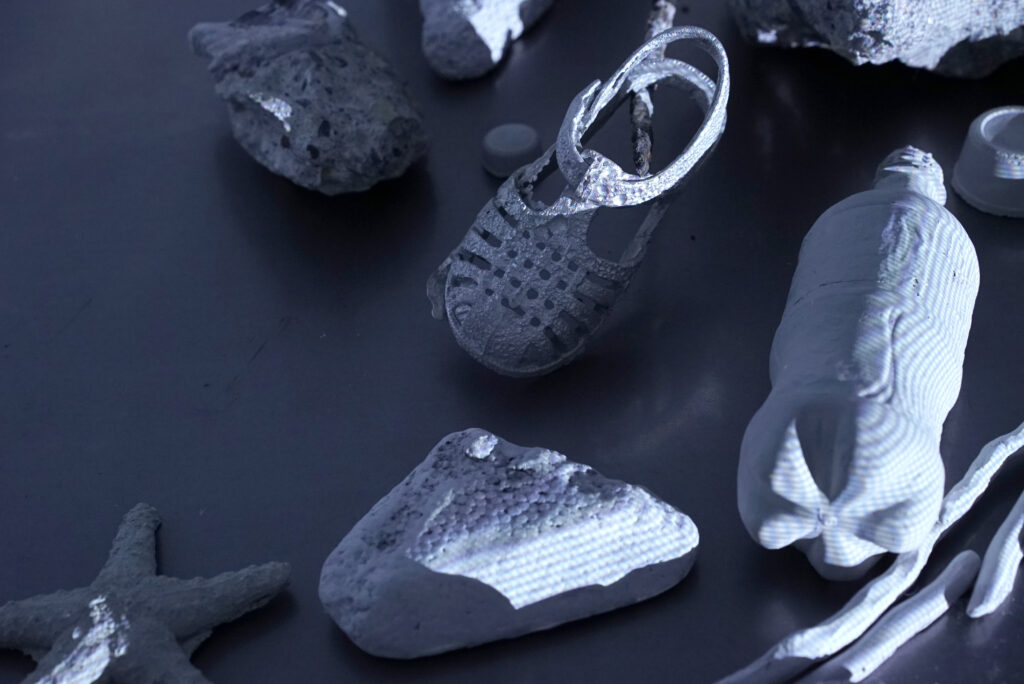

The objects of Wrack Line, familiar and mutant, concrete, cement, gypsum, pewter, lead, steel, aluminum, wood, rope, seashells, and glass, lie on a steel bed (6’x14’).

A discarded gas can, a lighter, a latex glove, flip flops, a hospital mask, a smashed plastic water bottle, a toothbrush, a styrofoam cup make me think of the plastic bag found at the lip of the Mariana Trench.

If you grew up going to the Jersey Shore (any shore?), you will feel a cultural familiarity in this wrack zone. (I remember needles and diapers and horseshoe crabs, too. What was in your wrack zone?)

Trash eternalized not by plastic but the bone matter of cities (concrete) and pewter (a memorializing medium). Fossilized. Ossified.

As if a human rhyme with jellyfish there is a child’s lone plastic jelly sandal cast in pewter. Quite exquisite, it seems to almost sparkle, a memorial to cosmic abandonment, the kind evoked so monolithically in David Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress:

“Was it really some other person I was so anxious to discover…or was it only my own solitude that I could not abide?”8-speculates the haunting novel’s protagonist, Kate, who is, perhaps, the last human on earth.

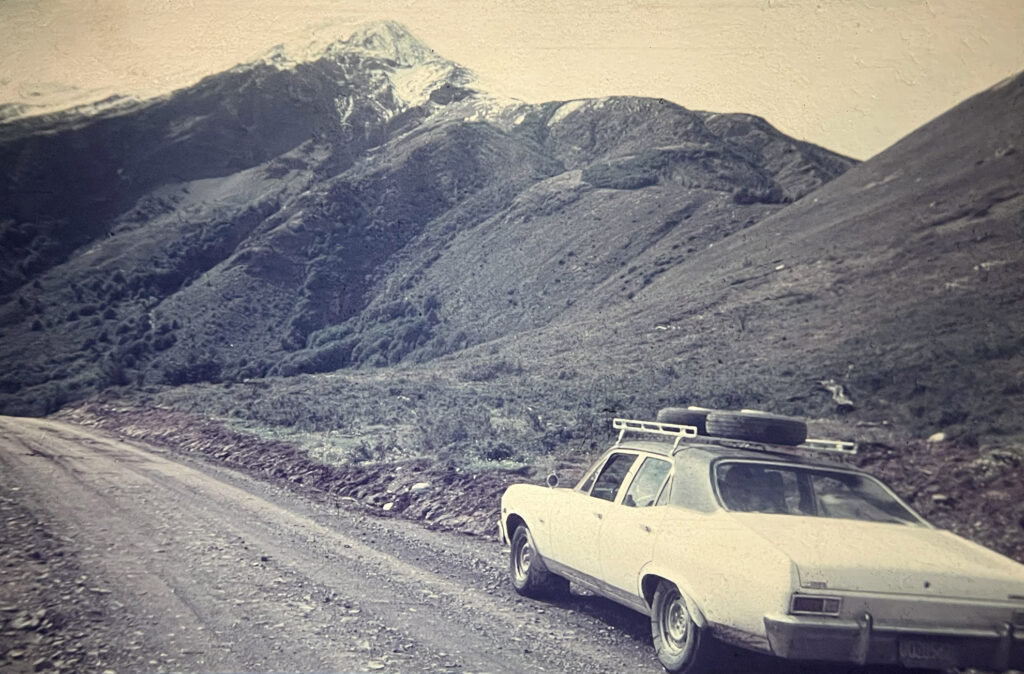

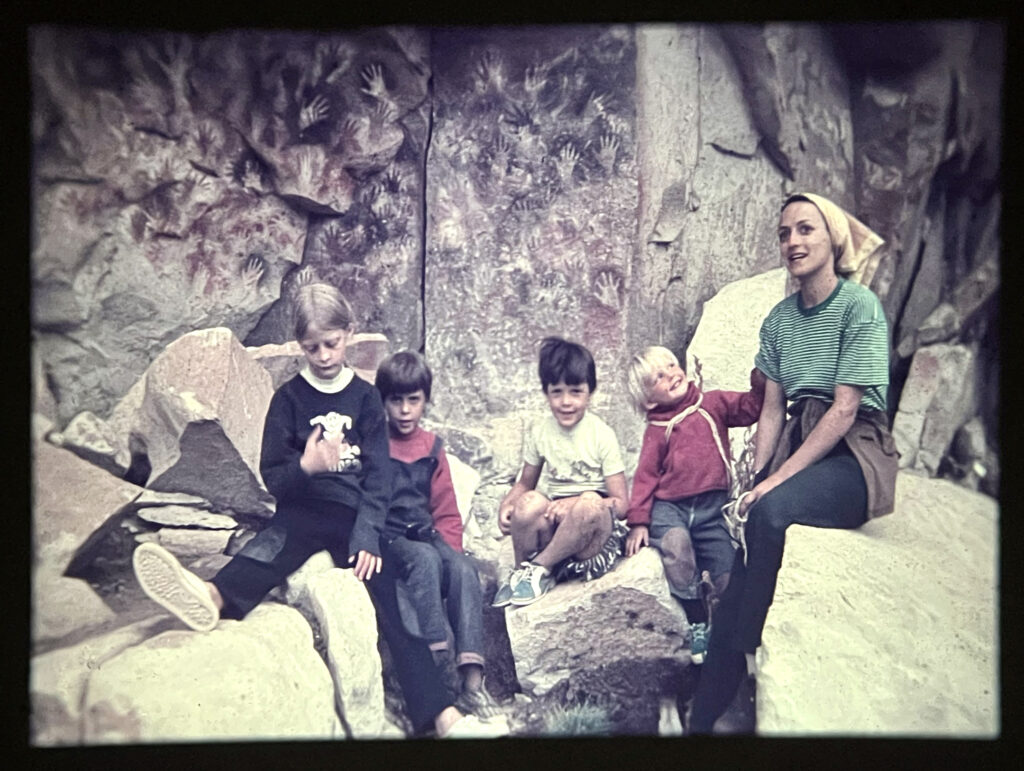

Solitude in another sense is echoed in Alexa’s account of growing up in Patagonia:

I lived with my family in Comodoro Rivadavia, a city that is on the Atlantic coast of Patagonia. North of us there were penguin colonies. We would go on long camping trips piled up into a Peugeot 404 sedan, and later a Chevy Nova. We had to travel with several spare tires, extra fuel, water, food, a fire extinguisher, etc. because there were no amenities and most of the roads were gravel at that time….One could camp for weeks and not see another person. At the time, I didn’t realize how adventurous these endeavors were. Camping was not a popular activity in Patagonia in the late 60s/early 70s. On one trip, my father had to put out a fire in the trunk of the car, caused by an electrical problem. Raindrops sizzled on the hood…. On another breakdown, we had to sleep in the car while my uncle walked miles in search of help. It was wild and inhospitable at times, but because we did these activities with my parents, we felt secure…

After immigrating to the USA life changed dramatically. I was close to 10 years old. The next time my siblings and I returned to Argentina, I was sixteen and my parent’s marriage had fallen apart. At age 22 I did a backpacking trip to many of the places we had visited with my family. I wanted to ascertain that my memory of these places was true, and an actual place. It gave me consolation to know I hadn’t imagined it.9

In Wrack Line there are other objects, organic and nautical–driftwood, starfish, a sailboat’s anchor, ship twine, an oar, chunks of coral or concrete debris… the similarity is telling.

Alexa recounts from Seven Tenths: The Sea and Its Thresholds (by James Hamilton-Paterson), “the centuries long dispute about the nature of coral–whether it is animal or plant–as it turns out, it is an animal that lives in symbiosis with algae which allows the polyp to secrete stone and thus build coral reef. I thought of the concrete used to build human infrastructure as a giant reef.”10

Wrack Line is also a little wack, an exquisite corpse not without its ostensibly surreal chimera–a conch shell blooms a human ear, a disembodied hand grasps a seashell.

As part of the whole these mutant relics portray an associative relationality–hands seek seashells at the seashore, ears stop to listen.

They are of, what Ursula LeGuin might call, a realism of a larger reality.11

Relics of the relationship between humans and the sea, relics of this contact and entanglement.

Relics that say touch and listen.

In the indiscriminate leveling plane of the wrack line the line between human and nature is wrecked, recast, reframed.

Cast in flat, neutral grays, the relics of the wrack line become surfaces for the large-scale video projection of crashing waves that fills the walls as you enter the room.

These moving images of the sea reward numerous visits or sittings with cameo appearances from the rock, tree, bird, and human worlds I won’t reveal here, tho I am interested in sharing the way Alexa writes about their disappearances:

There are moments when the ocean breaches the raised beach bed, spraying violently at the viewer. I think of these moments as erasures and use this shot between the scenes of people. The horizonless scene of the foamy, creamy-white ocean acts as a final cleanser and eraser. I repeat several scenes where the water and foam inundate the wrack line and there is no longer a horizon.12

Aeolian rhythms of ebb and overflow shape what we see seawise and hear.

The audio, by fittingly named Artifact Shore in collaboration with Alexa, fills the room with a soundscape synthesizing wind and waves crashing upon a beach, along with distortions of the sounds of a highway (per Alexa: “the whirr of tires creates a resonant hum not unlike that of the ocean or a river,”13) sinking/creaking vessels, the calls of the endangered albatross and blue whale and wind (there it is again) and more.

There is a desolate consolation in the continuousness of elements beyond us and their mystery–(if wind is volitional air, whose volition?)–lest we make the mistake of the Ancient Mariner in his encounter with the albatross:

And I had done a hellish thing,

And it would work ’em woe:

For all averred, I had killed the bird

That made the breeze to blow.14

The perpetuity of the wind and waves (sound and sea) blows clean the non-perpetuity of the I, its imperialisms, plastics, pleasures, pageantry, and annihilating impulse.

Wrack Line opens us to a threshold wisdom.

There is no explicit or self-righteous moralizing or shaming of an environmental crusade in this immersive tableau but a revelation of what is, in which seeming dualities blur– air/water, absence/memory, pollution/possibility, human/more-than-human.

In the ossification of everything, we feel present in a nature that is not other but a totality that includes us.

The Second Room: Undersea/Subconscious

You walk into a room as if into the sea.

You have to literally walk through the tumbling, turgid waves and soundscape of Wrack Line to move into the next room at Dreamsong.

“I, too, overflow; my desires have invented new desires, my body knows unheard of songs. Time and again I, too, have felt so full of luminous torrents that I could burst–burst with forms much more beautiful than those which are put up in frames and sold for a stinking fortune,”15 writes Hélène Cixous in “The Laugh of the Medusa.”

In the psychic space of a step or two you traverse fathoms.

A bronze cochayuyo waves at you.

“Bull kelp (Durvillaea Antartica), or cochayuyo as the local Chileans call it,” Alexa explains, “attaches itself to the rocks at the edge of the Pacific where its tendrils sway dramatically and erratically in the aggressive surf like submerged Medusas with heads of living snakes.”16

Human fingers rise from the orifices of barnacles, emerging from their sea-skin, to point this out.

You are in a zone of fascination and/or mortification.

Of “tombs, time capsules, gold mines, and time bombs.”17

Of the dreams of gorgons “fast asleep, soothed by the thunder of the sea….the moonlight glisten[ing] on their steely scales, and on their golden wings.”18

The mythopoetic is certainly invoked, particularly in La Sirena, a death mask of a woman serenely listening to a seashell, rebar from a corral chunk of concrete rising behind her, as if from a broken off wing.

La Sirena is listening; are we listening to the siren? The alarms? The sea?

The dream logic pervading this room brings to mind Thoreau’s “Read not the Times, Read the Eternities,”19 but revised: “Listen not to the Times, Listen to the Eternities.”

In the event of confusion, there is a wall of three concrete-cast conch shell headphones to directionally guide your listening.

The listening booth at Medusa’s liberation party for monstrosities of the subconscious.

We might hear beyond the wind’s howl in such headphones (would that we could) a prompting to imagine “a post-human, life-sustaining ecology of repair” (Alexa on her 2022 La Maravilla).

Listen to the sea / Listen to the wind / Listen to the more-than-human.

There are relics to remember the story of human coloniality and the delusion of human supremacies:

a bronze, sunken clippership called Derelict (derelict: from Latin derelictus ‘abandoned’, past participle of derelinquere, from de- ‘completely’ + relinquere ‘forsake’) drips in its wreckedness

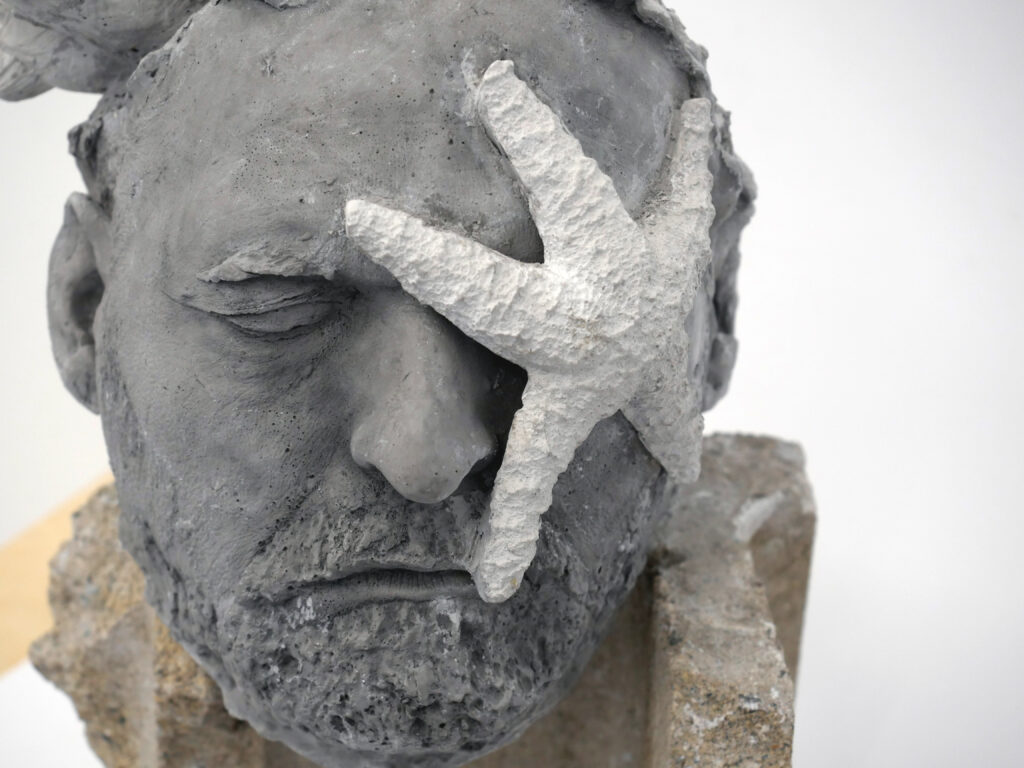

a death mask of a perturbed mason whose face a starfish has suctioned itself to like a pirate’s eye-patch

and supernatural mutations that get us to ways of thinking that dissolve the distance between human and wild:

conch spawns ear

nautilus spawns hand

latex-gloved hand spawns plastic bottle.

Alexa Horochowski, Nautilus, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Dreamsong.

Alexa Horochowski, Nautilus, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Dreamsong.

Alexa Horochowski, Landfill, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Dreamsong.

Alexa Horochowski, Landfill, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Dreamsong.

Alexa Horochowski, The Mason, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Dreamsong.

Alexa Horochowski, Derelict, 2013/2024. Courtesy the artist and Dreamsong.

Alexa Horochowski, Derelict, 2013/2024. Courtesy the artist and Dreamsong.

Alexa Horochowski, Barnacle, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Dreamsong.

Alexa Horochowski, Barnacle, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Dreamsong.

The human elements emerged in these mutant figures much without Alexa’s explicit intention:

In 2021 I traveled to visit my father (86 years old, family patriarch, surgeon, amateur black and white photographer, pilot, rancher then olive farmer, renaissance man, intrepid individual) and wanted to cast his hands with alginate. My bag was lost at the airport and by the time I got it I couldn’t make the mold. The following year I again visited my father but focused intensely on video-documenting everything at his home in Los Molles, Argentina. He passed in April 2022. I mention this because the human body imposed itself on my work without my consciously deciding to pursue this trajectory.20

In this light–the loss of the father in a time when toxic patriarchal structures are oozing their contaminates, asserting their terror, and crumbling–I feel a compassion for these hands looking for other existences.

They are also funny, in a gorgon-laughter way: “You only have to look at the Medusa straight on to see her. And she’s not deadly. She’s beautiful and she’s laughing.”21

Under the Sea-Wind invites this reversal, a revelation of the subconscious (where modernity has exiled its wild), to see the play and the breathtaking poetics in turning this world–its wrack lines, its relics, its wack associative offspring–to stone.

It was, after all, poetry (pegasus) who flew from Medusa’s throat.

She speaks in stone. And concrete. And pewter. And bronze.

This reliquarium breathes the visual silence of solitude, the eerie stillness of the eye of the storm.

It is literal concrete poetry at the literal end of the world, in the psychic space of Rachel Carson’s colorless night: “Everywhere was blackness–a thick and velvet blackness in which sky was indistinguishable from water.”22

The expanse of the no-horizon moment alone is not eternity without its contraction and wrack line.

Through a capacious curiosity that bends time, Alexa brings us to her Patagonia: “It is an open space without boundaries that I can access mentally. It is where I go when I am focused on the process of making art. . . .[where] I get lost in observation and discovery.”23

To get harrowed and whirled and bemused and petrified in a kind of wordless vastness is to meet this Patagonia that lives in Alexa as “wind, expansive horizon, movement, wonder, solitude, introspection, and keen observation.”24

To get there may entail “adjustments in our thinking.”25

To be under the sea-wind, Rachel Carson advises, “requires the active exercise of the imagination and the temporary abandonment of many human concepts …. For example, time measured by the clock or the calendar means nothing if you are a shore bird or a fish, but the succession of light and darkness and the ebb and flow of the tides.”26

To walk into a room and feel the sea-wind’s rhythmic eternity is to remember a much vaster reality of which we are mutant and part.

Under The Sea-wind is on view at Dreamsong January 12-February 23, 2024. → More information