Glitching the Glass Wall: Formidable Static

Culminating a series on digital culture and cyberfeminism: how glitching technology and persona can create cosmic potential for liberation

The glitch as formidable static

When I was a kid there were channels, restricted channels that one could only access by being extremely patient. Waiting for the precise moment when the otherwise glitched, blurry image would turn clear. If only for a nanosecond, I saw what I was merely imagining. These were mostly deemed the “illicit” channels—Showtime, Cinemax After Dark—where shows like the Red Shoe Diaries and Hotel Erotica would play. I had fantasized all sorts of risqué events occurring on the other side of the flickering screen, only to briefly be met with people engaged in innocuous activities. Was the glitch real? Was what I imagined real? Was the truth reality?

To be suspended in reality, one must first be suspended in disbelief, to be dipped in the chaos before fully understanding the non-chaos.

And while the actual cause of the pixelation was ultimately electromagnetic interference or basic cable restrictions and not some sort of alt-reality I wasn’t privy to, these graphical glitches forced me into a dimension beyond. The ultimate skewed perception. Because what you see is not always an axiom.

The glitch as a circumvent

In lieu of seeing a glitch as a failure, a brokenness, what if we greeted it as a conceptually delightful refusal? Coining the term “glitch feminism” in 2013 as a socio-techno construct (or rather de-construct) of gender and sexuality, author Legacy Russell invited us to welcome the glitch as “the error a passageway” to constructing better worlds. In Pauline Nguyen’s review of Russell’s 2020 Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto, she explains,

“To break, to dismantle, to fail fantastically in the face of a machine that expects us to keep carrying on as if it isn’t stifling and isn’t programmed to reward some and marginalize others. It is to carve fissures in existing, oppressive systems and its limitations on who we might be and what realms we might inhabit.”1

For those of us who grew up in the great divide of digital dualism—existing before and during the internet—the separation between online persona and IRL (or AFK, “away from keyboard” as Russell defines it) became a distinguishing part of our social dilemma. What do we share and with whom? What is real? What is curated? Online presence was our brief chance to jump realms, to depixelate the image. Using A/S/L (age/sex/location) became discriminating factors of who we were—or who we wanted to be: avatars. Do avatars dream of a virtual renaissance? Maybe it’s tangential but it’s still worth questioning.

Once you see the glitch, you start seeing it everywhere. Investigating the glitch demands repetition. I’ve been heavily immersed in it for the better part of a year, discovering artists who may not fall into the category of glitch art per se, but who are investigating tech in a number of nuanced reflections—intersections of digital culture, virtual fluidity, the disillusioned detachment of body, separation of self. These new media and digital artists see tech error and persona error in similar lenses, and use them as portals to explore the social and political ramifications of our layered relationship to cybernated content.

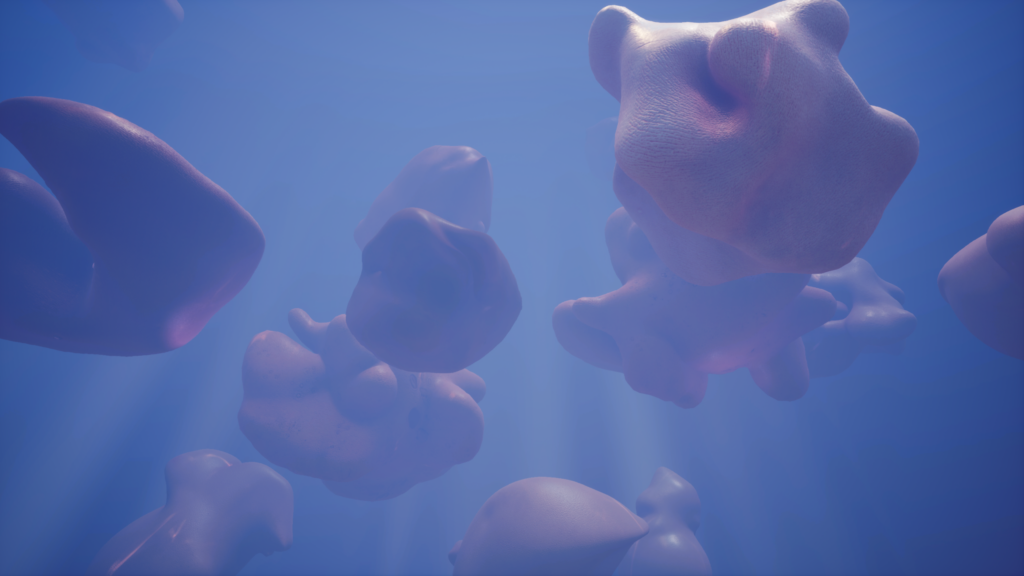

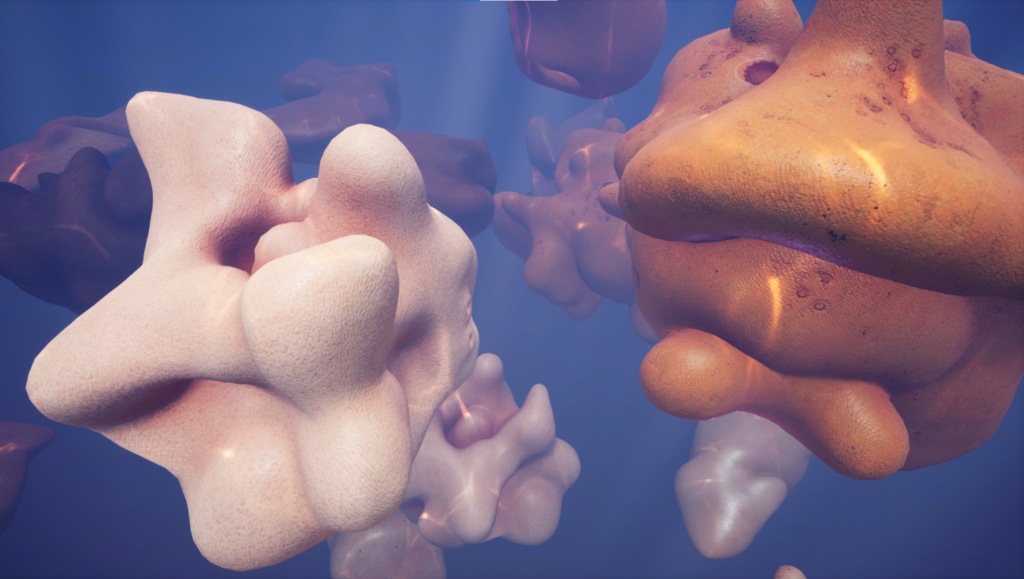

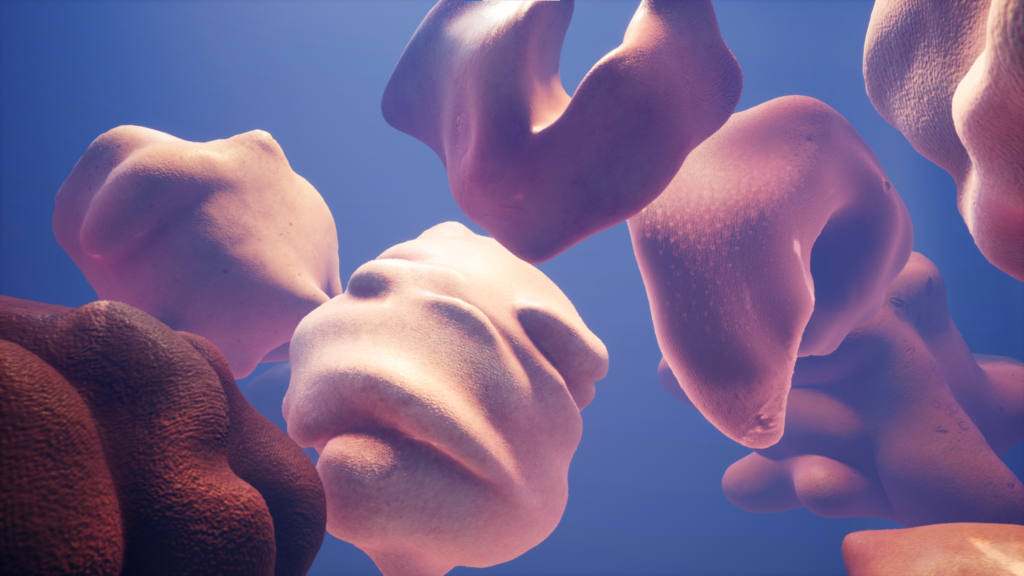

In the virtual reality piece May the moon meet us apart, may the sun meet us together—a Fabbula-commissioned work—artist Rindon Johnson intimately pairs viewers next to a series of limbless, ocean-dwelling creatures named Bists, where one can find themselves without a body, floating in gentle ambiguous seas, as orby gelatinous critters slowly multiply and rub up against one another.

“Fluidity of the octopus and the fluidity of the Bists, of their meeting, of their nameless, full body emotions speak directly to the necessary entangling I believe is crucial to live within our multivalent every changing planet, to maintain a presence and openness. I look to the meeting of the octopuses and I see that we must become used to the event as a form of cherishable catharsis, we must feel deeply, reaching our hands out, swimming slowly, feeling the hairs, the skin, the pores of our fellow beings, spinning and commingling into the future.”2

I am reminded of Octavia E. Butler’s pivotal trilogy Lilith’s Brood, in hindsight a wildly advanced series populated by fluid, genderless orbs and setting the foundation for what we now understand as gender fluidity before we achieved the vernacular surrounding it.

What can we gain by being without a body? How can it change our perception of presence? What formidable static is between it all?

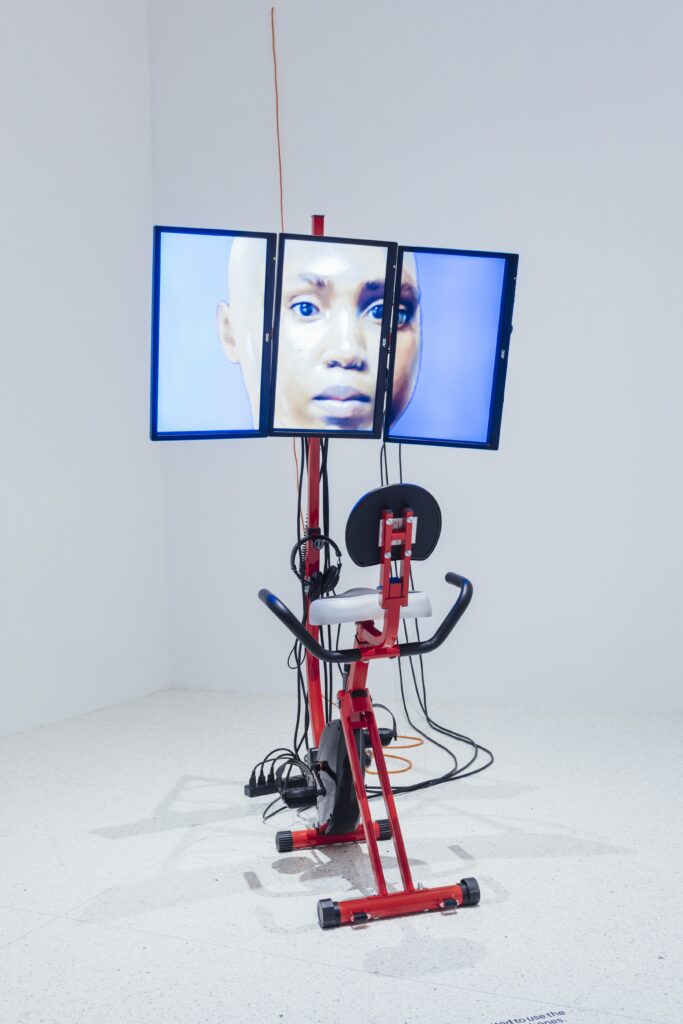

In 2018, Elodie A. Saint-Louis explored the work of media artist Sondra Perry as she “engaged in the discourse around racial uplift through a clever manipulation of technology, while providing incisive commentary on the hidden labor Black bodies are constantly asked to perform.”3

“Perry ‘appears’ in Graft and Ash in disembodied form, specifically as an animated head that floats in and out of virtual space. Although constructed from her image, the visible avatar is a collective and representative we, definitively separate from the ‘real’ Perry.”4

Perry suspends us in disbelief and reality incongruently. Much like Johnson’s work, Perry implores us to inhabit the virtual space as we float in and out of our bodies. What intimacy comes from disconnecting? Can we detach from the burden of body memory? Does the virtual allow us to escape embodied trauma? Because, as Russell says, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a body. And one is not born, but rather becomes, a glitch.” What does it mean to curate for the body when the physical is informed by or rejected by the mental?

In 2018, The Cut ran an article about the AI model Miquela Sousa, better known as Lil Miquela, the AI avatar who took the internet by storm as a fabricated enigmatic Instagram influencer, leading the author on a reality tangent about Gucci’s fall 2018 show,

“Inspired by Donna Haraway’s 1984 A Cyborg Manifesto, the collection was a hybrid of actual and fantastical references. Two models carried replicas of their own heads down the runway, while another cradled a “dragon puppy” that looked like it had come straight from Game of Thrones. Maybe it was the jet lag—I was in Milan for Fashion Week—or maybe it was the dizzying effect of good art, but something moved me to text my editor, seated in the front row: ‘Those dragons weren’t real … Right?’”5

Strangely, this reminds me of the corridor of severed heads from tyrannical sorceress Princess Mombi’s palace in the 1985 Disney film, Return to Oz, each head possessing a different personality. The penultimate persona divide. What would Princess Mombi’s avatar be?

If we can fabricate something so real that we’re left questioning our own connection to time and space, is there a way to interrogate the digital real in the same cosmic centeredness? Are we afraid of AI because it challenges our perception of reality or because it disrupts our personal digital dualism?

In Russell’s chapter “Glitch is Cosmic,” she describes,

“A person’s virtual avatar is as real in cyberspace, or the ‘digital real,’ as their offline self. We can travel beyond what we typically think of as a body (that becomes gendered) to consider our virtual selves. If the body is ‘inconceivably vast’ like the cosmos, then to queer is to expand potential for being. To glitch is to disrupt systems, sledgehammering holes into taken-for-granted logics of oppression—a queering in itself.”6

The glitch as amorphic, queer

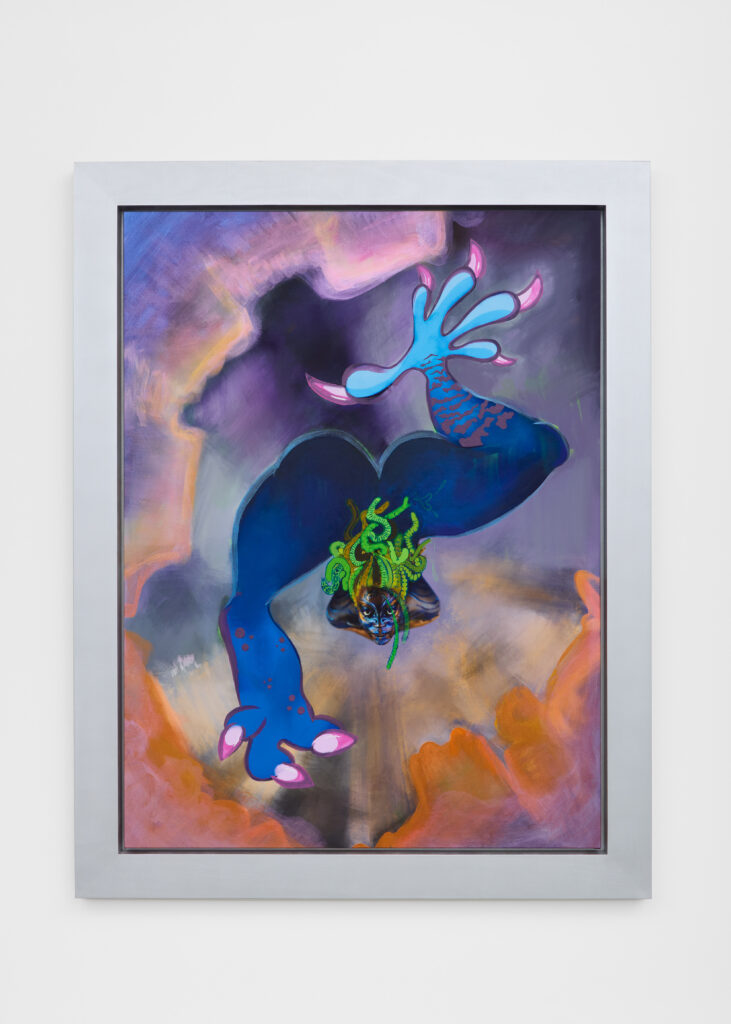

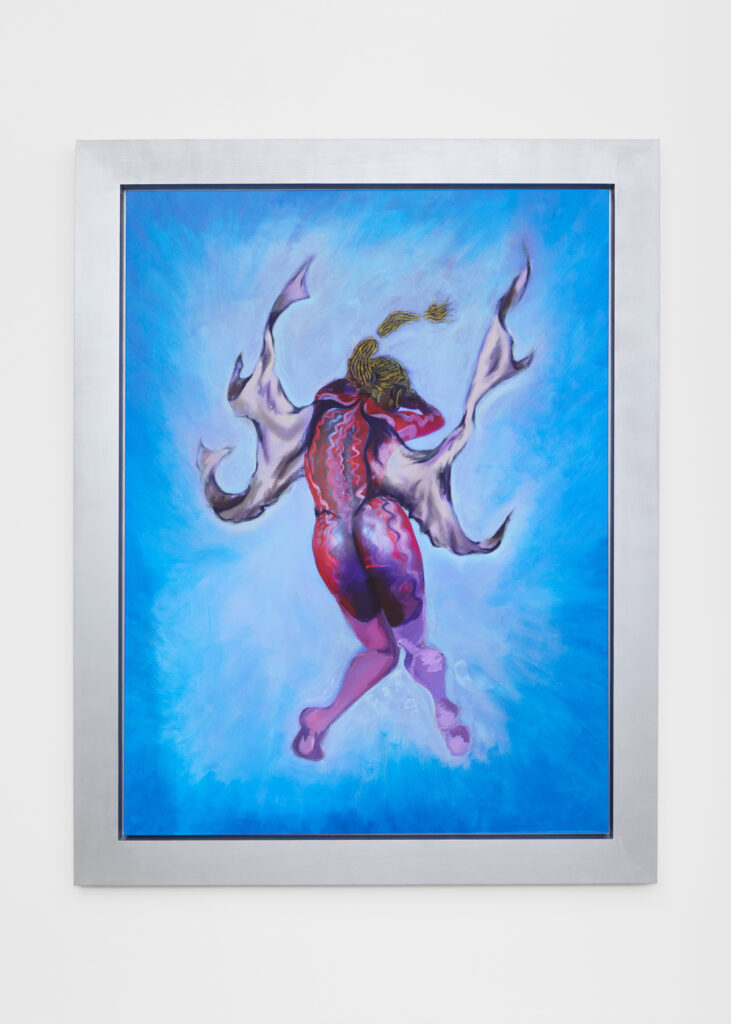

In Juliana Huxtable’s, USSYPHILIA—featuring her AKIMBO SPITTLE series, currently on view at Fotografiska Berlin—the multimedia artist uses mythological, animal/human chimera creatures to pose questions on limiting identity, while challenging the gender constructs through psychedelic realms defying what our definition of “human body.” Much like Russell, Huxtable welcomes us to travel beyond, to queer the cosmos. If the “body” ceases to exist in liminal standards, do we shift attention to the cracks or the pieces that fell from them?

Juliana Huxtable, SCALING, 2022. Courtesy the artist and Project Native Informant, London.

Juliana Huxtable, SCALING, 2022. Courtesy the artist and Project Native Informant, London.

Juliana Huxtable, BIPED CHOP, 2022. Courtesy the artist and Project Native Informant, London.

Juliana Huxtable, MUCUMBA MIDNIGHT TYPE, 2022. Courtesy the artist and Project Native Informant, London.

Juliana Huxtable, A STRETCH, 2022. Courtesy the artist and Project Native Informant, London.

Juliana Huxtable, POST, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Project Native Informant, London.

Juliana Huxtable, POST, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Project Native Informant, London.

The glitch as manifesto subtext

To understand the divide, we must go to the source. In 1991, the self-declared “mercenaries of slime” VNS Matrix ushered in their rallying cry, a quippy cyber feminist manifesto in which they unabashedly proclaimed the title of the “saboteurs of big daddy mainstream,” the symbolic viruses or glitches of the overwhelmingly cis-male tech world/cyber space. Hot on the heels of the likes of Valerie Solanas’s “S.C.U.M. (Society for Cutting Up Men) Manifesto”—a counterculture text of male irrelevance—they strove to disrupt the inherent marker of technology as assigned to the male-gendered-default and reclaim it as the divinely feminine digital landscape. And while their anarchic poetry provided a cybercultural freedom for some, its archaic and vitriolic language—engaged in oppressive legacies of the cyberfeminist genesis—isolated others.

The glitch as cyborg

As if the 90s didn’t already feel disjointed and contradictory, in the same decade, Donna Haraway released her own manifesto daring to challenge the hierarchical body-based binaries and biology-based exclusionary language VNS Matrix failed to recognize: i.e., trans and non-binary experiences, BIPOC voices, the basic concepts of intersectionality. Can we fear the machine if we are the machine? Or maybe we are the severed head of the machine.

As Haraway writes, “We are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism—in short, cyborgs,”7 we approach the cyborgian dream of dissolving body and gender to make space for the beyond. This metaphor was closer to this intersectional digital utopia but still had its flaws. For Haraway’s very own cyborg dream had militaristic origins, thus placing them in direct contact with patriarchal lineage, creation stories, linear progress, dichotomies. How do we live in a post-gender social realm while being a man-made machine? And yet, while we become essentially digitized, increasingly mediated by technology, are we not cyborgian?

When the Post-Cyber Feminist International met in 2017, their conference set out to examine what new technologies can still offer, how to use them positively, and how online spaces might be queered and hacked.

“Cyberfeminism circa 1991 had glaring insufficiencies. The first ramraid on technology’s sanctified halls was a gender war, paying little heed to the political economy of technological production and consumption… But that first action, with all its insufficiencies, smashed the field wide open and these gaps provided pivot points towards a more intersectional cyberfeminism.”8

Where cyberfeminism followed in the footsteps of a wave of feminism that left a lot of voices out of the conversation, Russell’s glitch feminism sought to invite voices beyond the binary, to pivot, to think of using online space as a way of world building. Using this template—a cyber activist world beyond the binary, queered—digital art and new media can exist as a tool for defying how our bodies can be read. Glitching the glass wall, if you will.

In 2019, Paul Boyé and Grace Connors extended the slime metaphor into a larger collaboration, Mercenaries of Slime, exploring cyber-feminist futures and post-humanism, in this case likening the body to slime. They ruminated,

“Through the figure of slime, we have a desire to produce emancipatory images of slimy-becomings. These systems of play and pleasure emerging from queer gooey materials and adaptable technocultural spaces are capable of housing spontaneous entities, novel artistic practices, political actions and scientific invention. But, what does it mean to imagine worlds like these if the logics at their core appear identical to the systems of control, subjugation and imperial domination that such figures are opposed to and unable to exist within?”9

Picture yourself as slime. If we are these adaptable gooey materials able to slide through portals simply by changing our molecular structure, how do we occupy a space—i.e., cyberspace—that is in itself infinitely uncontained? In a digitized era where there is calculated curiosity, limitless curation, and intentional mendacity, how do we define what is an error? How does one define slime?

If we set out under the informed guise that technology is not neutral (like Nguyen argued), that it is not innocent in the divide and isolation it creates, while we choose names, definitions, texts for our bodies to be read by, then we can use these theories, manifestos, and bodies of work to reflect and crystallize the biases already present in society. These systems and cyber spaces, at their origin, worked best for the identities that designed them: mostly cisgender white men. When others attempt to participate, they often encounter errors, failures, and glitch.

The glitch as liberation

If we all glitch, will it lead to liberation? I think of the work of Huxtable, Johnson, Perry, Haraway, Russell—those who have traveled through the glitch in their work and fused fluidity in virtual space—and the words of curator and artist Katie Peyton Hofstadter:

“Glitch forces failures and triggers disorder but can also create space in which reclamation and liberation can be practiced.”10

Maybe we’re doing this all wrong, waiting for the glitch to clear. Maybe it’s the opaque, the blurred, that we should be anticipating, patiently awaiting to take us to the unknown space. As a cyborg, a chimera, a piece of immutable slime, the machine’s severed head, consider that the revolution will be intentionally pixelated. Do not attempt to adjust your screens.

For more, see Juleana Enright’s curatorial statement for the exhibition “Anomalies,” presented by La.dy.like. → Read more