American Fascism as Aesthetic Experience

Identifying the symbols and myths of fascism as a warning sign for its political actions

“The United States of America is in practice and in fact a Fascist State. Moreover, it was the first among Nations to become a Fascist State!”1 While this may read as a condemnation of the US government, the author, Floyd Hatfield, instead writes with pride. These lines open an essay appearing in the March 7, 1939 edition of Liberation, the journal of the Fascist Silver Legion of America, published out of Asheville, North Carolina from 1933 to 1941. Founded by William Dudley Pelley the day after Hitler became chancellor of Germany, the Silver Legion, or Silvershirts, set out to restructure American government and society around Nazi ideals—a mission that landed Pelley in federal prison for sedition. We tend to think of these fringe fascist groups as importing a foreign ideology and forcing it into an American context. However, as Hatfield suggests in the passage above, there is something deeply American about fascism, something woven into the fabric of our national, historical trajectory from past to present.

What is fascism? What is aesthetics?

Fascism is notoriously difficult to define. Some believe it is mostly meaningless because of its overuse as a casual slur. Others believe that it should only be used to refer to early twentieth-century Fascist movements.2 A more recent contingent of theorists have offered more encompassing definitions, but defining is inherently limiting: it draws borders around things and concepts for ease of understanding, directing our attention away from processes and subtleties, from social and political interstices that might transcend ideology or policy. In his 1995 essay, “Ur-Fascism,” Umberto Eco proposes a means to reconcile the ideological idiosyncrasies that make a universal definition difficult:

“The notion of fascism is not unlike Wittgenstein’s notion of a game. A game can be either competitive or not, it can require some special skill or none, it can or cannot involve money. Games are different activities that display only some “family resemblance,” as Wittgenstein put it. Consider the following sequence:

abc, bcd, cde, def

Suppose there is a series of political groups in which group one is characterized by the features abc, group two by the features bcd, and so on. Group two is similar to group one since they have two features in common; for the same reasons three is similar to two and four is similar to three. Notice that three is also similar to one (they have in common the feature c). The most curious case is presented by four, obviously similar to three and two, but with no feature in common with one. However, owing to the uninterrupted series of decreasing similarities between one and four, there remains, by a sort of illusory transitivity, a family resemblance between four and one.”3

Articulating resemblances involves engaging aesthetics as a language of image, representation, and semiotics.

The word “fascism” is itself a visual metaphor containing myth: the root of the word, fascio, means in Italian “bundle” or “sheaf,” but it also bears resonance with the Roman fasces, an ax encased in a bundle of sticks symbolizing the authority and unity of the state, which brings to mind Aesop’s fable “The Old Man and His Sons.”4 Semiotically, a bundle of sticks becomes the idiom “Strength Through Unity.” As early as 1935, Walter Benjamin noted the connection between aesthetics and fascism in his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” writing, “Fascism sees its salvation in giving these masses [the newly organized proletariat] not their right, but instead a chance to express themselves. […] The logical result of Fascism is the introduction of aesthetics into political life.”5 If it is fascism that brings aesthetics into politics, then aesthetic analysis becomes a tool for identifying fascism.

Aesthetics typically refers to the philosophical study of beauty and art, which certainly are at play here in how reliant fascists are on style, but I mean the word more generally. In viewing art, we become at times absorbed by the work—a kind of suspension of disbelief that immerses us in a phenomenological world-experience. This happens in our everyday engagement with social spaces as well—community, politics, ethics all function as world-experiences that absorb us into a sensorial reality. In his book, Ten Theses for an Aesthetics of Politics, Davide Panagia defines an aesthetic experience as “one in which one has a sensation of incisive conviction regarding the presentness of an object, despite the fact that there is no source or site of evidence that will count as necessary or sufficient to determining the validity of that incision.”6In other words, an aesthetic experience is one that feels true but is not verifiable—a kind of judgement. I engage aesthetics to show how American fascists stylize themselves through image, symbol, storytelling, and myth in order to construct a secondary analysis of the worldhood of American fascism—one that uses absorption to inspire incisive conviction outside of the scope of truth.

The Aesthetic Mythology of American Fascism

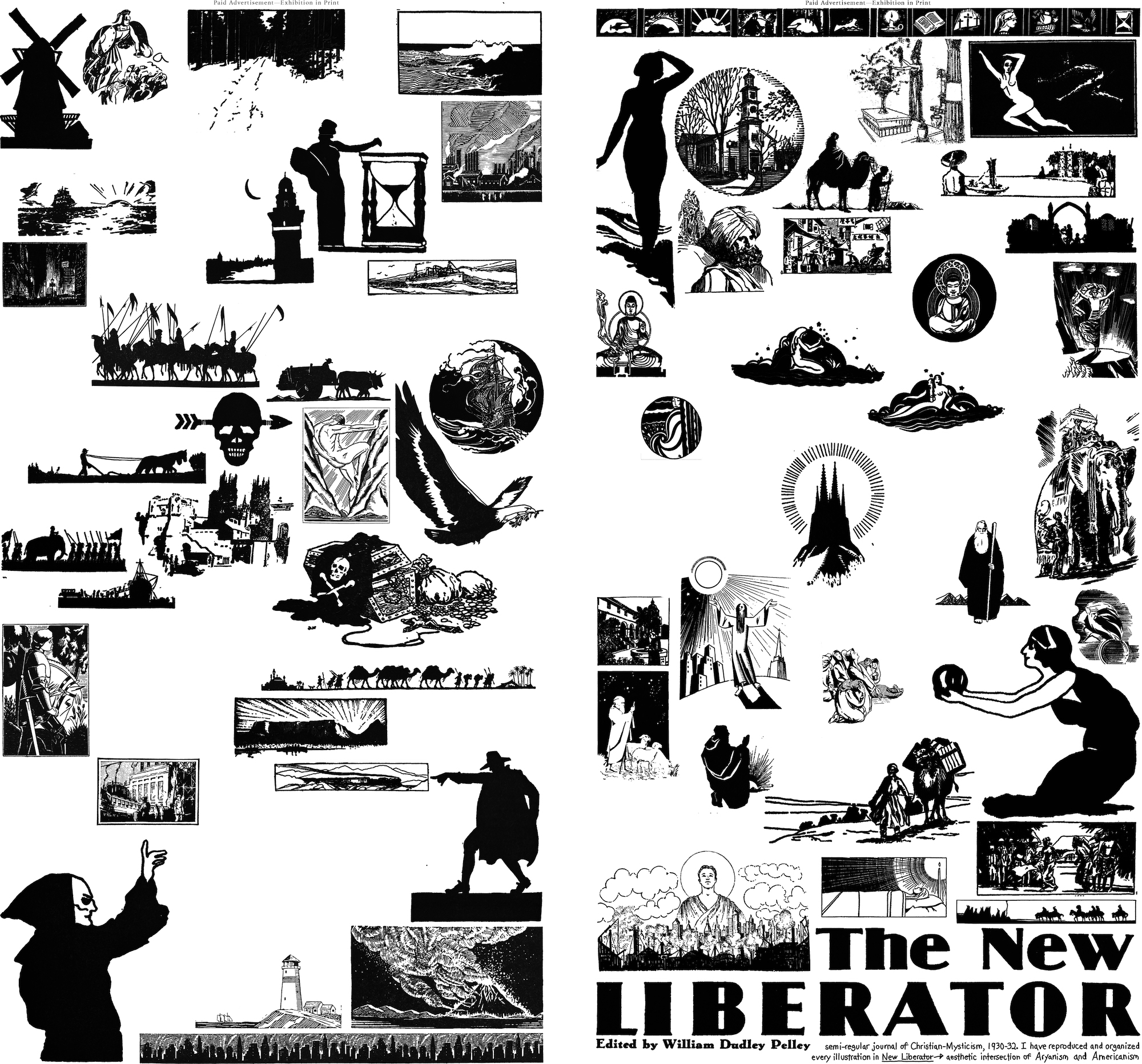

In 1930, William Dudley Pelley published his first journal, The New Liberator, which appeared semi-regularly for nearly two years. His articles throughout the periodical are a strange blend of antisemitic fearmongering, crisis manufacturing, Aryan mythology, and a supernatural capitalist conspiracy that would save American Christians.7 The text of this journal is not overtly political; you will find neither a fasces nor bundle of any kind, and yet it feels deeply fascist. And feelings, as Robert Paxton notes, play right into the hands of fascist world-building: fascism seeks “to appeal mainly to the emotions by the use of ritual, carefully stage-managed ceremonies, and intensely charged rhetoric.”8

As a journal of Christian Mysticism, it’s unsurprising to find crystal balls, nude nymphean women, demons, menacing figures, and scenes that vaguely reference the Bible. But this gives way to South Asian and Middle Eastern stylizations, hallmarks of Aryan mythology. Aryanism restructures European history around the myth of Germanic or Nordic peoples that conquered Europe, invaded the Indus Valley, and invented Vedic Sanskrit.9 And from the mythological dust of this Indo-European imperialism, Ancient Greece and Rome emerged. The New Liberator is full of vague references to Aryanism through both text and image, illustrating the centrality of this worldview to Pelley’s thinking. But this is contrasted with a second myth: that of white supremacy and US history, advanced through the semiotics of colonialism. Ships navigating turbulent seas, farmers tilling the land, a colonial church, a bald eagle, cityscapes, industry, and even pirate paraphernalia all work to construct an origin within the violence of colonization and imperialism.10 It’s not enough to control and police the land—the white race must cite origin too. In the absence of historical facts, aesthetics drive this fascist world-building.

Consider the image of the farmer tilling the landscape, turning the soil, transforming something wild and unusable into something stable, habitable, civilized. Contextualized with the preceding myths, the farmer becomes a symbol of settler colonialism. Images of majestic landscapes and quiet pastoralism join those of Aryanism and colonialism to construct a fascist worldhood in the American context. And like Nazism, the fetishization of an idealized landscape is paradoxically coupled with the celebration of technology and industry, illustrated in The New Liberator through images of factories and cityscapes. Near the title, you’ll find an illustration of a saintly white figure standing above—as if presiding over—a sea of skyscrapers and smokestacks, which also returns us to the centrality of Christianity to this American world-building.

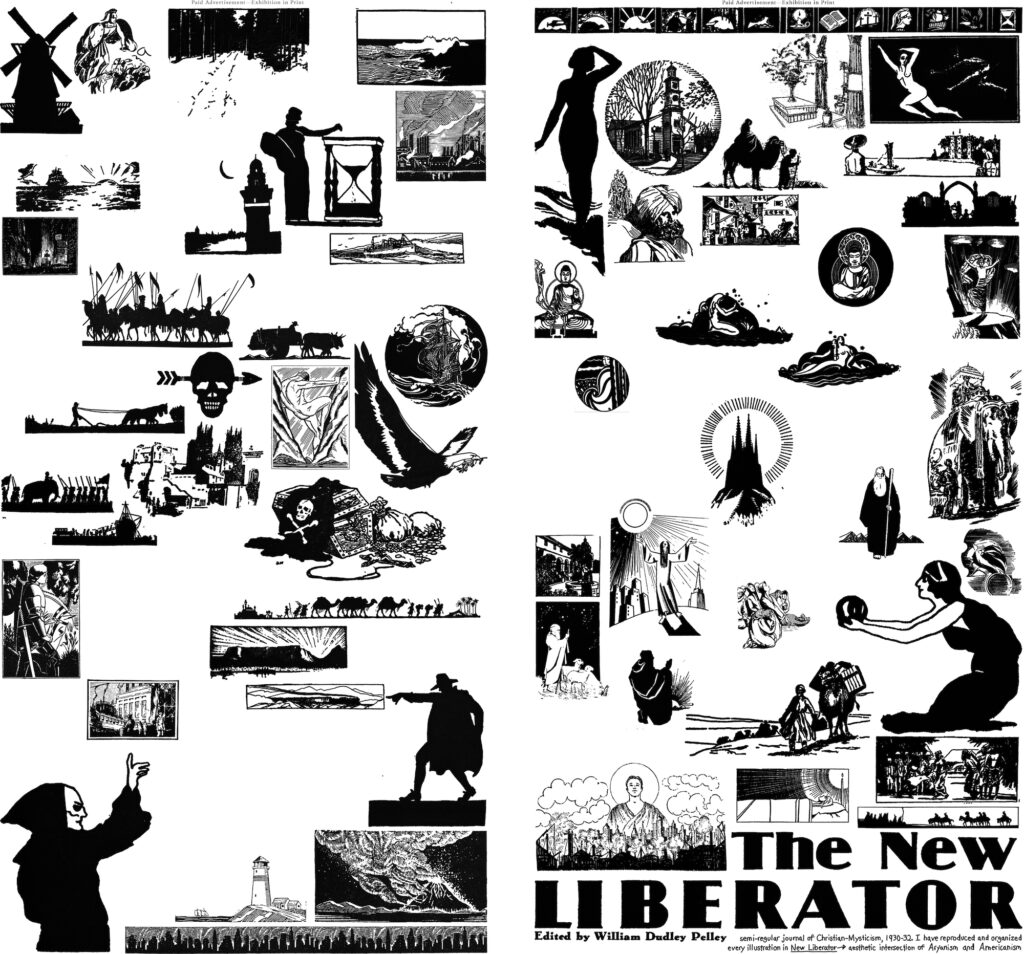

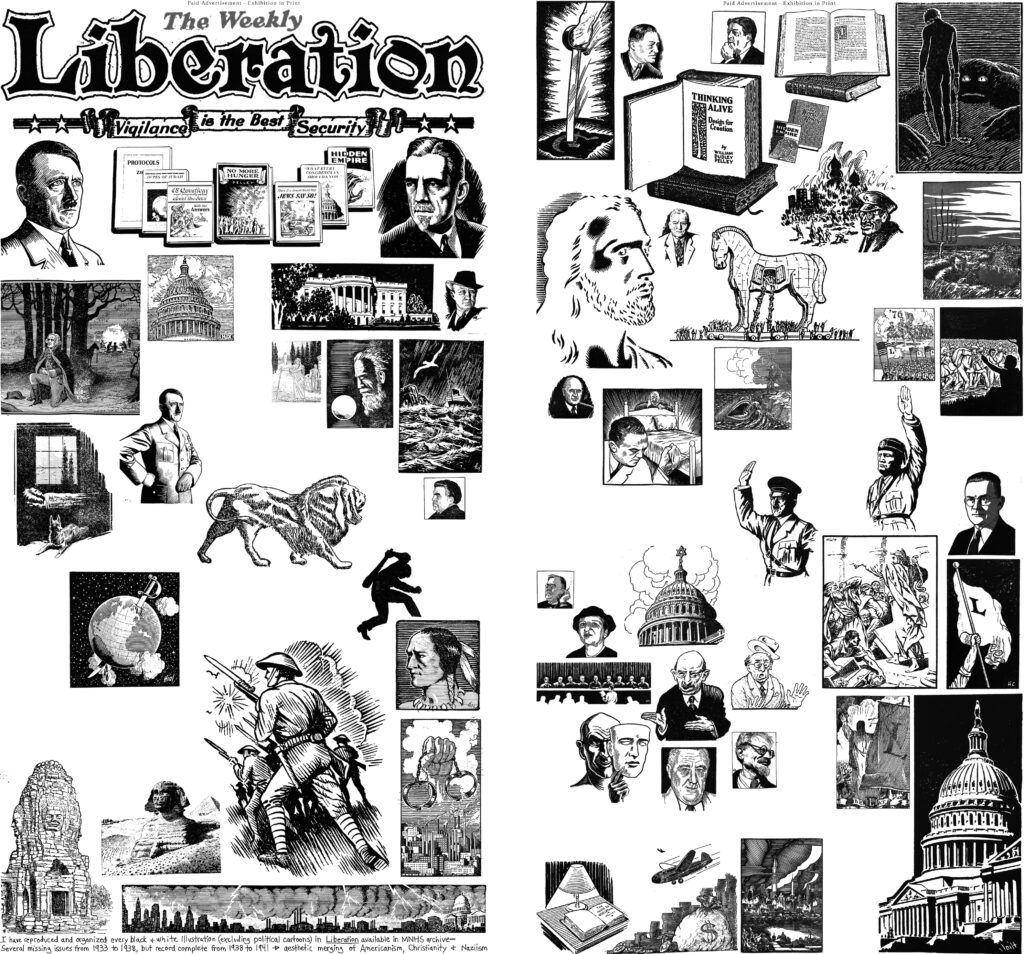

Liberation 3-13, ed. William Dudley Pelley, 1933-1941.

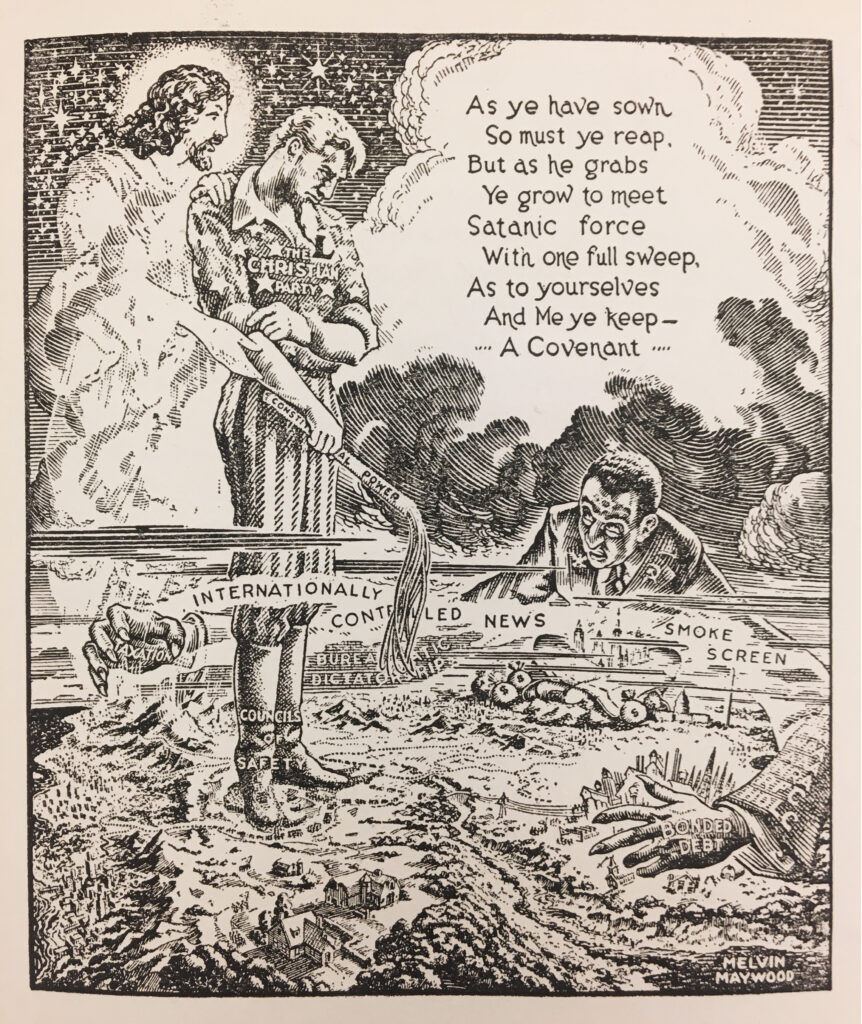

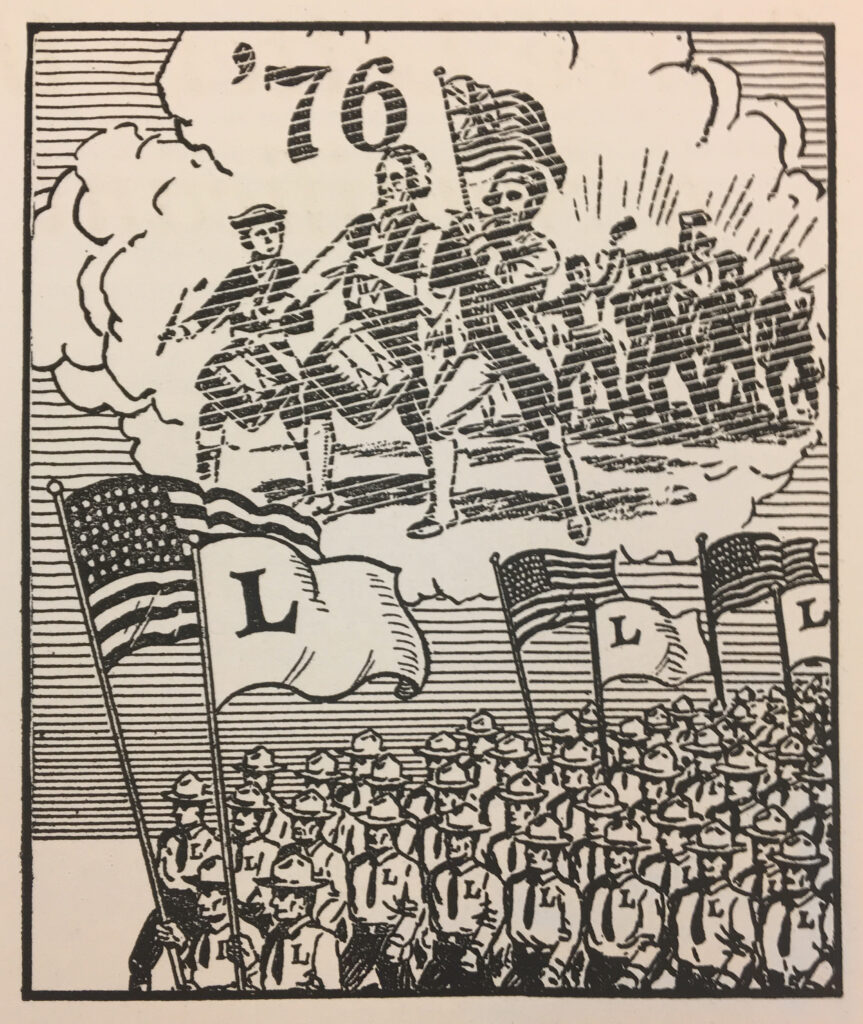

It is a small step from industry to war, and for fascism, war is beautiful, war is heroic, war is “the only cure for the world.”11 While The New Liberator contains some depictions of crusaders, the aesthetics of war are fully realized in Liberation: armed soldiers, marching revolutionaries, a Trojan horse, a muscled lion, a sword piercing the Earth, George Washington praying on the eve of battle, and even Christ brandishing a scourge. The scourge was adopted as the emblematic weapon of the Silver Legion, referencing the biblical passage in which Christ drives money collectors from the Temple. By mixing the myths of American revolutionary origin and the righteous might of Christianity, federal buildings become temples and the violent cleansing of corruption—the draining of the swamp—becomes a moral obligation. But this serves more as a ploy for genetic purification, an excuse to disenfranchise Jews, people of color, and other “undesirables,” while maintaining an unjust social structure that concentrates power and wealth in an already-corrupt few. In this context, the scourge becomes the slaver’s whip, a weapon for enforcing white supremacy and the plantation-state, emboldened by racist Biblical interpretations that equate white with goodness and black with evil.12

The pursuit of genetic purity has a long history in the United States, particularly through the interwar period. In Minnesota, failed Farmer-Labor politician Charles Dight convinced the state legislature to legalize sterilization in 1925. The passage of this law and the infrastructure developed to support sterilizations of “feeble-minded” peoples was supported intellectually by the University of Minnesota: letters in the Dight Papers at the Minnesota Historical Society include correspondences from the Dean of the Medical School, the founder of the Anthropology Department, and even University President Lotus Coffman all voicing enthusiasm for Dight’s eugenic crusade.13 While eugenics was seen as the height of modern science, a tool for purifying the human race and breeding intelligence, it disproportionately targeted the poor and people of color, enforcing a white supremacist moral agenda rather than a (pseudo-) scientific one. Recent scholarship14 has revealed how much US eugenics laws inspired Nazi racial hygiene, but the industrialized pursuit of genetic purity extends deeper into American history with the genocide of Indigenous peoples, residential schools, reservations, slavery, and Jim Crow segregation laws.

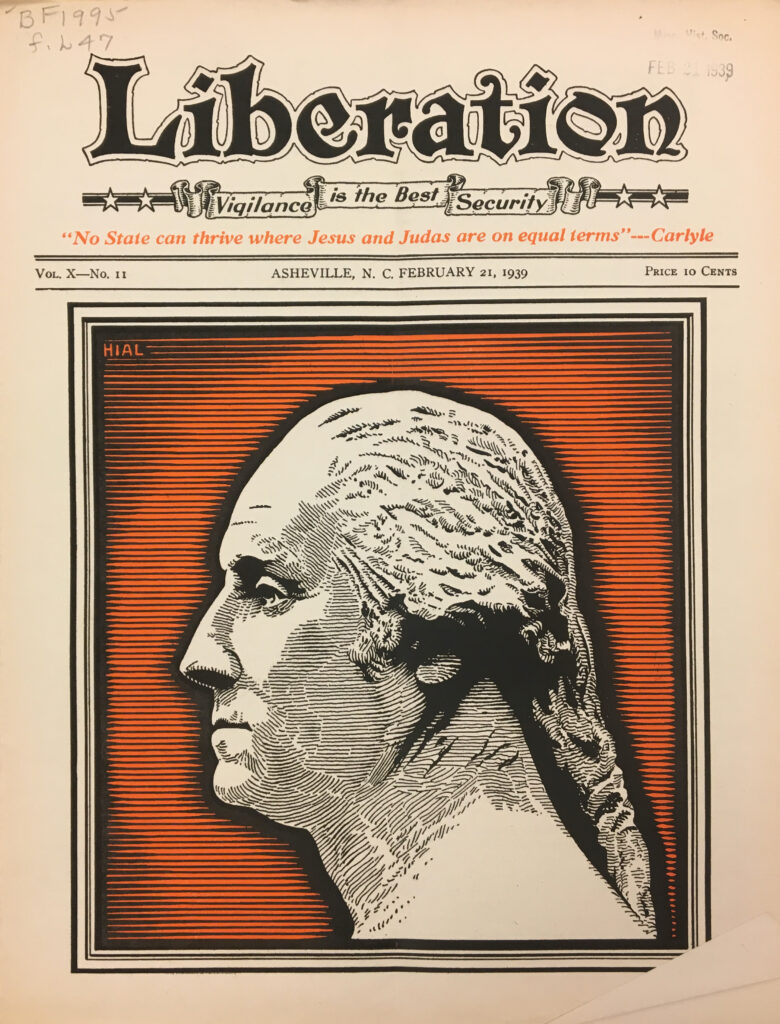

Cover of Liberation 10, no. 11 (1939), located at the Minnesota Historical Society Gale Family Library: FOLIO BF1995 .L47

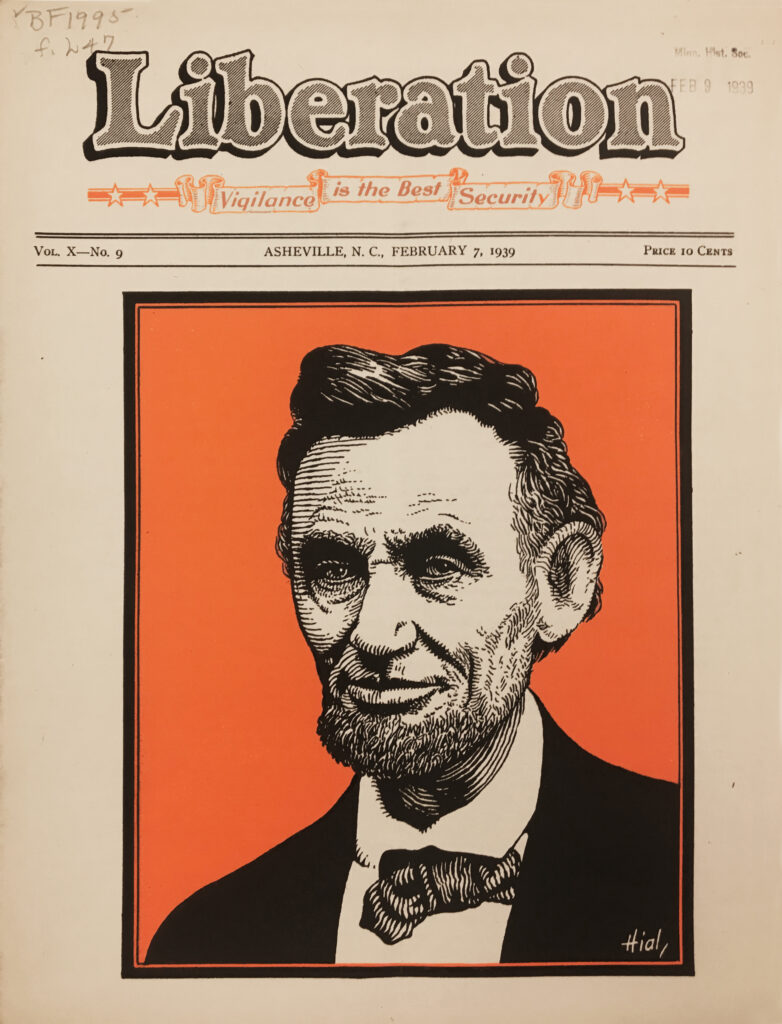

Cover of Liberation 10, no. 9 (1939), located at the Minnesota Historical Society Gale Family Library: FOLIO BF1995 .L47

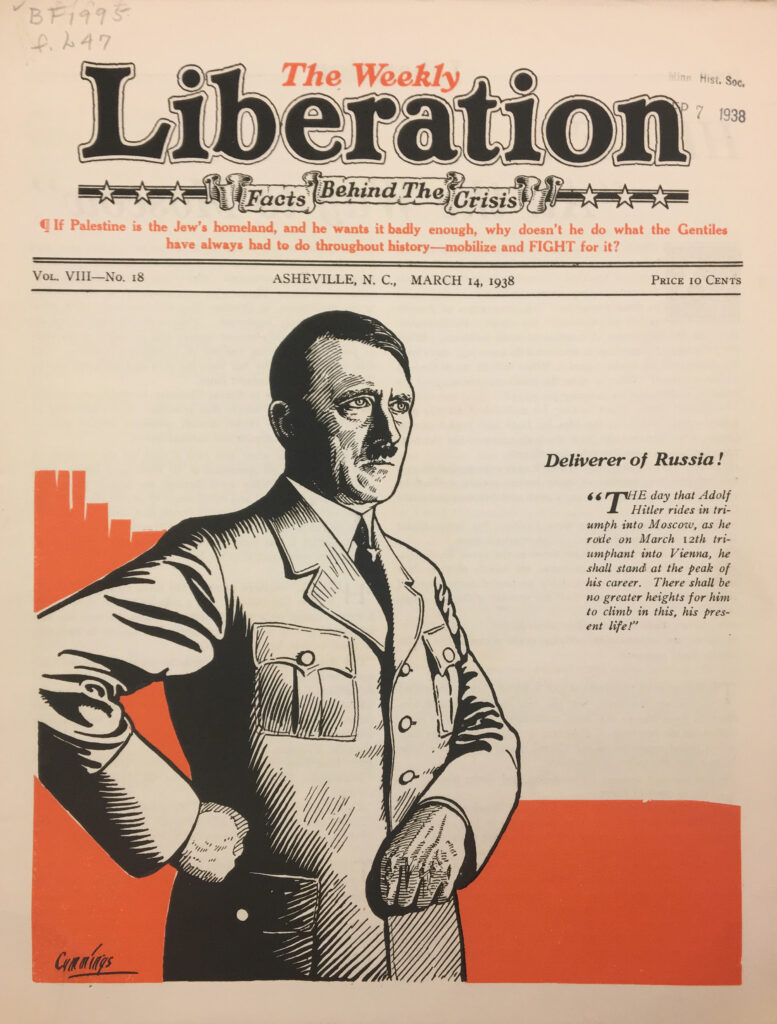

Cover of Liberation 8, no. 18 (1938), located at the Minnesota Historical Society Gale Family Library: FOLIO BF1995 .L47

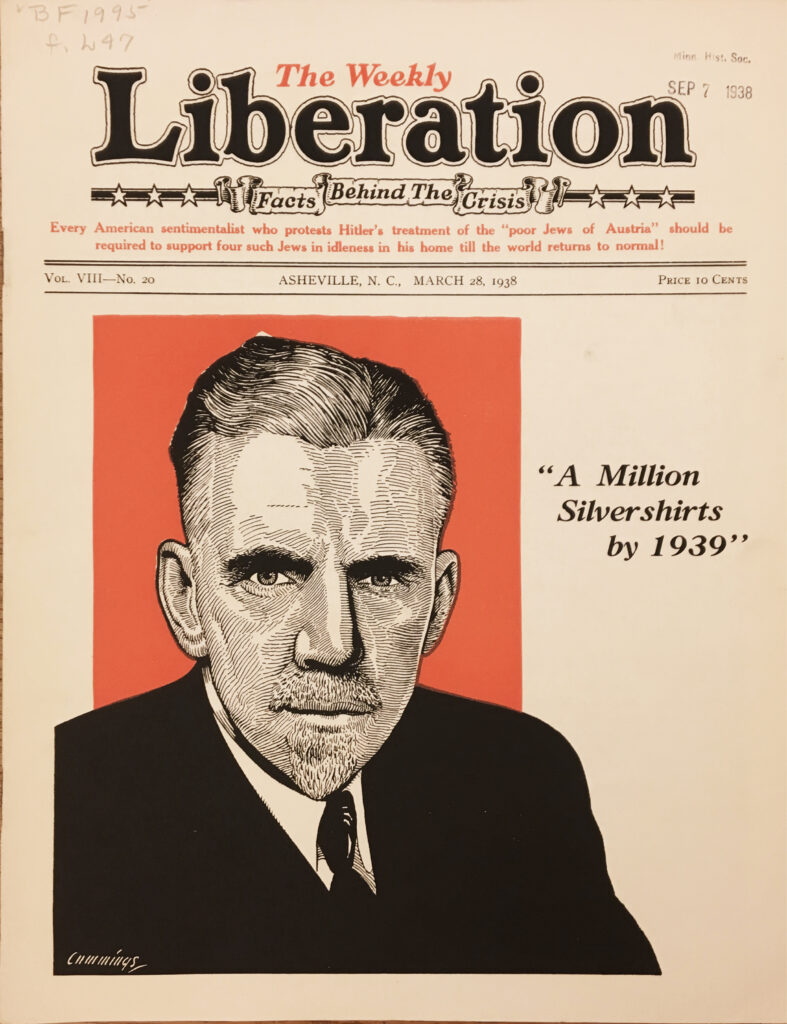

Cover of Liberation 8, no. 20 (1938), located at the Minnesota Historical Society Gale Family Library: FOLIO BF1995 .L47

US history already enshrines white supremacy and minimizes the crimes against humanity our white ancestors perpetrated, but Liberation further reinforced this narrative. A couple dozen issues depict founding fathers and other US presidents on their covers. These men are portrayed as heroes, forerunners of the Silvershirts, but Pelley also placed among these founders images of Hitler and himself, as if suggesting that these men belong together, that they share a singular lineage of supremacy and leadership—a bloodline. Elsewhere, an oft-repeated illustration depicts marching Silvershirts dreaming of marching Minutemen.

When we separate out the overt idolization of Hitler and the specific mythology of Aryanism from The New Liberator and Liberation, we are left with a clear aesthetics of American fascism, an ideological world expressed through image and myth, inspiring absorption: origin in the colonization of North America, whiteness, racial purity and paternal lineage, pastoralism, industrialism, glorification of war, revolution, and masculine strength, and the obsession with a mythologized version of the past.

Trumpism as an American Fascism

In July of 2017, William Connolly published Aspirational Fascism: The Struggle for Multifaceted Democracy Under Trumpism. Just one month before the Unite the Right white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Connolly concluded that Trump merely aspired towards fascism. For Trumpism to become fascism, it would have to “accelerate institutional racism, immigration bans, deportation drives, misogyny, selective police ruthlessness, the hegemony of one wing of Christianity, and military bravado […]. It would allow vigilante violence against vulnerable groups while maintaining a thin veil of deniability about the state’s support or tolerance of it.”15 This list continues for two pages, and many of his predictions have actualized in the past three years. But I’m not sure that we need a comprehensive checklist of policies and actions to define American fascism. As illustrated by Umberto Eco’s Wittgensteinian approach to fascism, policies and actions can vary widely from one manifestation to another. But more critically, a checklist requires actions or events to have happened; it operates through hindsight rather than in the present. Aesthetic analysis allows us to enter the world of fascism as it is being built before its policies or actions have manifested. Through aesthetics, we can observe the absorbing myth while remaining tethered to truth, as if in a diving bell sinking towards the abyss. Fascism must be countered at its moment of coalescence, and to do so we must engage its aesthetics, not its definition; we must first identify its imagery, symbols, rhetoric, and myth in order to prevent its impending political actions.

Consider this passage:

“The Silvershirts will not alter the American form of government.

THE SILVERSHIRTS WILL RESTORE IT!

[…]

The Silvershirts will attempt to restore the American form of government, but it won’t be a Democracy—it will be Republicanism. That this nation is a Democracy, or has ever been a democracy, is more blatherskite smokescreen. The Silvershirts will attempt to restore a Constitutional Republic—but with this addition:

They will see to it that proper safeguards are set up, so that no swarms of quasi-orientals in future may subvert its institutions to steal the nation blind and debauch its Christian stamina.

[…]

This country under a Silvershirt regime will be governed as little as possible—excepting that an utterly-looted Treasury, a prostrate and bankrupt Industry, and a workless population may make fiat labor necessary.

More than all else, a Silvershirt Regime—call it Fascist, Nazi, Populist, or Mugwump—will make rigorously certain that alien despolers are forthwith disenfranchised, their leaders lodged in Federal penitentiaries, and the scum of their evil reasonings scoured from press and screen.”16

These lines from Liberation mirror Trump’s rhetoric from the earliest moments of his campaign, a time when few were prepared to identify him or his movement as fascist. Trumpism built a world that absorbed the masses—and the more people the myth absorbed, the more power Trump and his allies gained, the more fascist policies were enacted. Power always comes first in fascist movements, and the absorbing aesthetic experience of American fascism, even prior to policy, ideology, and action, causes that power to balloon, supplanting truth with style.

You don’t need to ask the insurrectionists who stormed the US Capitol on January 6 what they were doing, why they did it, or what they hoped to achieve; they were absorbed in a fascist world of mythic origin, of white-American supremacy, of violence, colonialism, and imperialism. Their actions are an expression of the worldhood of American fascism visualized through flags (Trump, MAGA, Confederate, Gadsden, America First), symbols (orange hats, the “OK” hand symbol, 1776 memorabilia, Qs for Q-anon, Pepe the Frog, camouflage, Norse imagery), and even built structures (a noose and gallows, a rough-hewn wooden crucifix.)17

As a final thought, consider that the obsession with a singular leader, with a Trump or a Hitler, is an aspect of fascist propaganda.18 The cult of personality can fool both zealots and opponents through assuming an ontological link between movement and figurehead. Fascist myths are shaped over decades, even centuries, and the political structures that support a cultish leader never emerge from a vacuum. We can, and will, get rid of the fascist pageantry of MAGA hats, Trump flags, and Viking costumes—but the deeper and more difficult question is how we deconstruct a social and political armature that perpetually generates an absorbing, mythological world outside of fact and truth, inspiring incisive convictions of whiteness, racial purity, colonial origin, militarism, and limited franchise.

This research was supported by an Artist Residency at the Weisman Art Museum: https://wam.umn.edu/brooks-turner-legends-and-myths-of-ancient-minnesota/