Digital Culture and Art(ists) on the Verge

Sheila Dickinson reviews the latest "Art(ists) on the Verge" exhibition at the Soap Factory, featuring five Minnesota artists whose work addresses new media and technology: Chris Houltberg, Sarah Julson, Mad King Thomas, Asia Ward, Anthony Warnick

SURE, ART COULD REMAIN DETACHED FROM THE DIGITAL, virtual modes of social engagement that have inundated most everyone’s daily lives; artists don’t have to address those concerns. But at this moment of rapid cultural and media transformations happening right now, artists have an opportunity to offer timely insight and navigational methodologies that might help us get a handle on what all this change means to us, what this change does to us. Art(ists) on the Verge (AOV) is the main platform in Minnesota for such work: it’s an annual fellowship program that spotlights Minnesota artists who engage with new technology, either materially or conceptually. Selected AOV fellows are awarded a year of mentoring, provided with financial and technological support that culminates in an exhibition at the Soap Factory; through May 26, 2013, five local new media artists have work on view in the gallery for Art(ists) on the Verge 4. The artists’ works are incredibly varied, despite a shared interest in incorporating elements from and fostering encounters with burgeoning technologies.

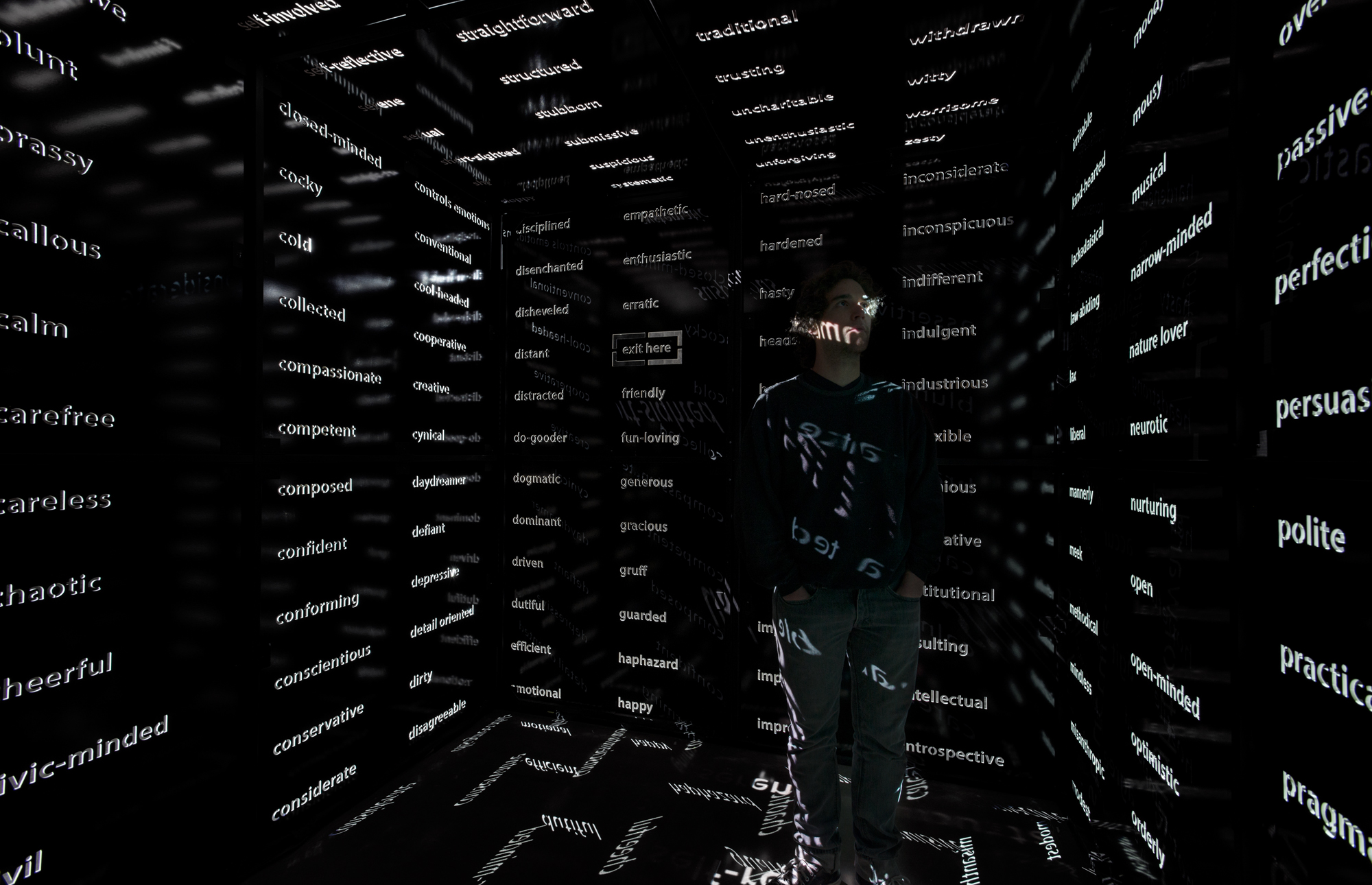

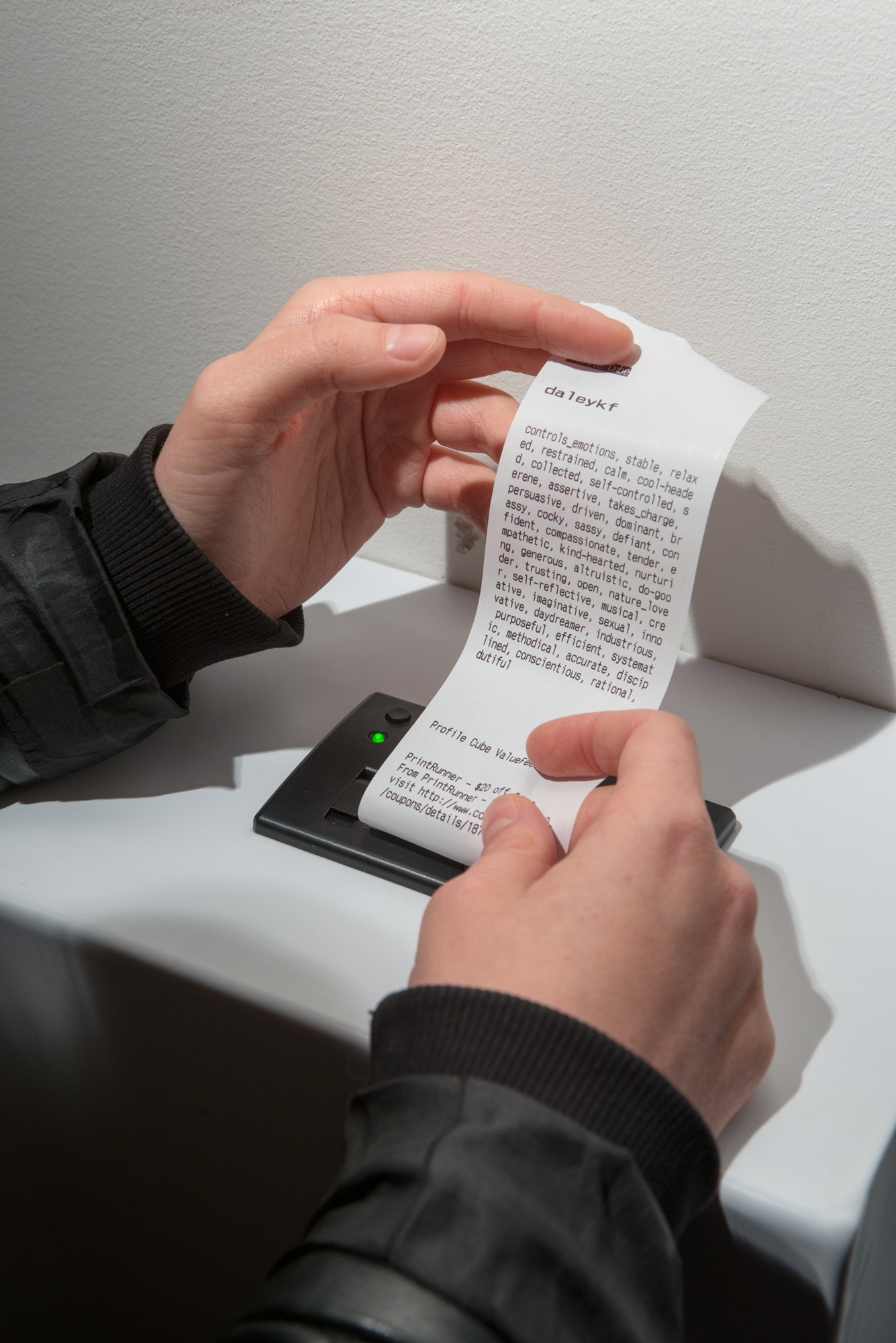

Directives, filters, mediators, communicators, barriers, routes, and translators flicker randomly, yet impeccably throughout the exhibition. There are touch screens to caress, phone calls to make, maps to read, library cards to fill out, even a dungeon to dive into. Conceptually confronted at every turn, the viewer participates with interfaces which repeatedly recall the unreal other-zone of the internet. In fact, the opening act for the exhibition puts cyberspace front and center: Chris Houltberg turns the analog-to-digital crank, re-imagining the Old World funhouse fortune-teller for the internet age. The viewer is greeted by a touch screen asking a series of questions: e.g. “Which Real Housewives do you like best?” or “Thumbs up or down for the robot?” Inane and hilarious, Houltberg’s viewer has to choose something, anything, so the game software he designed can “accurately” determine one’s personality; upon completion of the personality test, one gains entry into large white cube installed in the gallery. Once inside, adjectives projected on the cube’s walls surround the viewer on all sides. At the opening, you could see gallery-goers clutching the personality printouts provided upon exit from the cube, staring quizzically at the (intentionally contradictory) personality assessments printed on their receipts, tabulated from their responses to the initial quiz. Houltberg’s work asks us to consider just how much contemporary notions of identity are subtly morphed by all the seemingly innocuous web surfing we do — where each click of the mouse is recorded and mined for information which is indefinitely held to use for/against the user.

After following green highway signs directing the viewer into Gallery Two, four different maps are available to help one navigate Sarah Julson’s artistic terrain. Without those guides, the various pieces of her installation, This Way – video, fence, sculpture, steps to climb over a low wall – appear as interesting, but disconnected artifacts. But map in hand and following its colored arrows, the varied pieces aligned for me in unpredictable ways: my attention was drawn to imprints of hinges in the cement pieces o, in the video of a wood fence directly before me, while the completely enclosed circle of picket fencing suggests barriers surmounted, passed through. More broadly, the installation ponders borders maintained and borders superseded, with a nod to the global reach of digital culture, which defies the real-world infrastructures that police and constrain it. What’s more, the assemblage’s deeper meanings are only unlocked as the viewer moves within and through Julson’s work. Therefore, This Way partners well in the large space of Gallery Two with collaborative dance works by Mad King Thomas.

______________________________________________________

Nothing about this show is fixed or static. The artworks themselves remain in process, due either to the artist’s continual production or to the viewer’s complementary actions.But the work also questions the changes technology affects in us – in our social relations, our very sense of self.

______________________________________________________

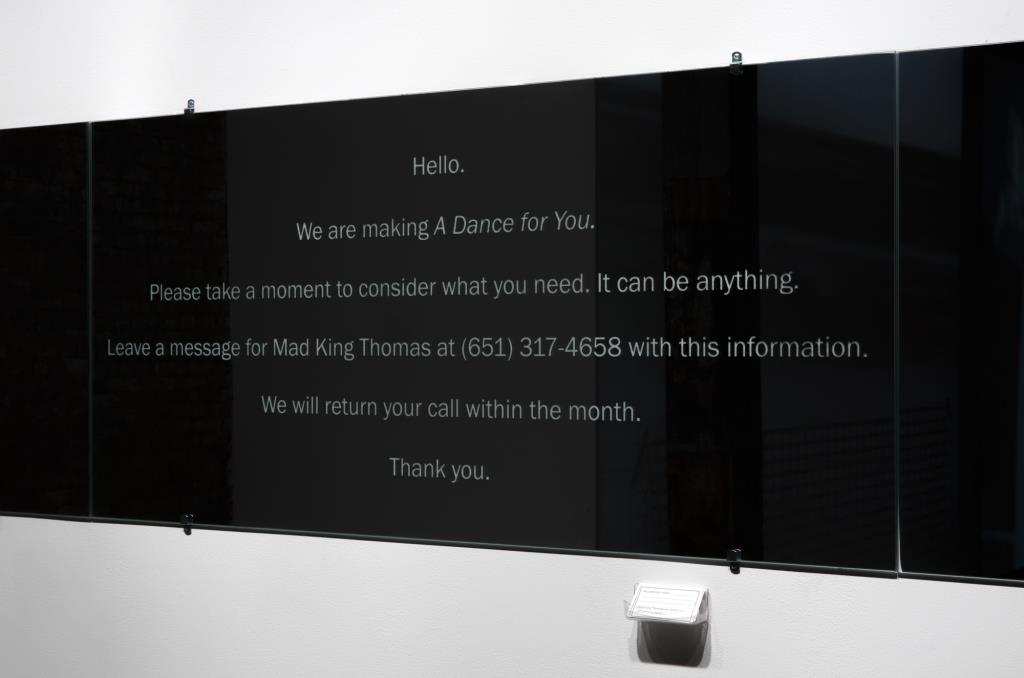

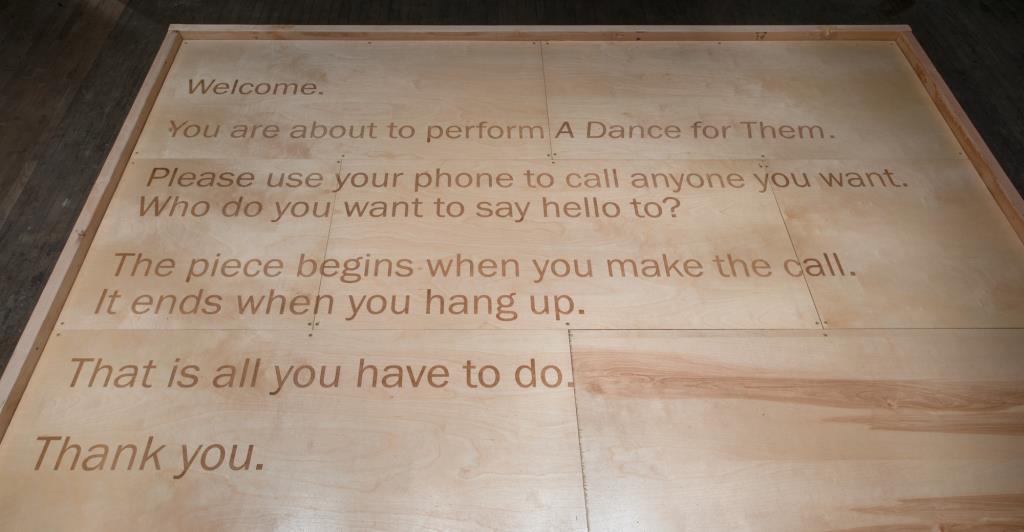

Mad King Thomas’s work comes with instructions, like cue cards, that prompt viewers to perform given tasks, should they choose to participate. Walk up the wooden ramp to approach the stage, and a spotlight beams down on you; words burned into the wooden floor tell you to make a phone call, to anyone. What ensues is an impromptu performance by the viewer, a Dance for Them in the form of a private conversation — the sort of thing usually handled discreetly in a corner — turned into a very public display. The social act of telecommunication, connecting emotionally but not physically – something now so normalized that most of us take it for granted — becomes something to be freshly appreciated, even valorized. A large horizontal mirror hangs at eye level next to the stage, with instructions also etched into its surface which ask the viewer to make another phone call, this time to Mad King Thomas, so that they can create, as the title suggests, A Dance for You. They also create a pun, intended or not, by presenting both mirror and stage. Lacan’s mirror stage theory insists that a person does not know oneself autonomously, but rather only through the eyes of the other, through one’s relation to another person — a paradigm for self-discovery that emphasizes connection, communication and collaboration.

There is nothing static or closed about the work in this exhibition. In fact, the artworks themselves remain in process, due either to the artist’s continual production or to the viewer’s complementary actions. The Library is no exception: Anthony Warnick has developed software that challenges the idea of the “classics”. Questioning the very idea of some precious, original and authentic source, Warnick turns the text of treasured classics into open source datasets that, put through his magic discombobulator, become something entirely new; Alice in Wonderland becomes a poem, and Lord of the Flies morphs into a screenplay with Grecian characters. Warnick created five different filters, such as translating Lord of the Flies into three other languages and then back into English; those filters alter the original texts beyond recognition – depending on your point of view, destroying or enhancing the them in the process. Seen through Warnick’s filters: one’s left with a sense that we know this book, and yet we don’t at the same time, much like the Dada quest to take the familiar and make it uncanny, strange (think: Meret Oppenheim’s Fur Cup). In Warnick’s Library installation, the viewer can leaf through the original texts, learn about these new/old books from a real-life librarian/worker (continually on site during gallery hours); one can lean on the work’s handmade plywood shelves and hear the whir of a nearby photocopier; on the way out, the viewer may fill out a library card to borrow a book, which can be picked up at the end of the show’s run or at Warnick’s artist talk on May 25. The Library is experientially rich and delightfully anachronistic with its workman-cum-software wizardry and warped classic texts.

All of the works in the show question the ability to absorb the changes technology creates in the texture of our daily lives – our social relations, our very sense of self. The viral aspects of technology means it has the ability to latch onto and morph our everyday lives, and these are particularly manifest in Asia Ward’s immersive environment. One engages the concept somatically here – by walking into what feels like the inside of some unknown organism. Ward’s installation works with and amplifies the already-eerie qualities of the Soap Factory basement: the space is dimly lit and there’s a just-audible whirring sound, reminiscent of the sounds made by the workings of a computer hard drive. Huge, white organic forms encase the entire space; filled with air, those forms light up as viewers approach, brought to life by human presence. Abstract and evocative, Ward’s work plays on common fears about the uncontrollable, overwhelming reach of technology.

You’ll leave the show with more questions than answers. Neither celebrating technology nor deriding its advancements, Art(ists) on the Verge instead seems simply to urge measured consideration, asking that we take a pause in the constant buzz of our tech-luxe world to think more fully on the implications of these technologies’ ever-forward march.

______________________________________________________

Related exhibition links and events:

Art(ists) on the Verge 4, presented by the Soap Factory in collaboration with Northern Lights.mn, is on view through May 26. Participating artists: Chris Houltberg, Sarah Julson, Mad King Thomas, Asia Ward, Anthony Warnick. There is an artist talk in the gallery at 2 pm on May 25. For more information on the exhibition: http://soapfactory.org/index.php. Find more about the Art(ists) on the Verge fellowship program: http://northern.lights.mn/projects/artists-on-the-verge/.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Sheila Dickinson is an arts writer and art history professor based in St. Paul.