Beyond Technique to Artistry

Lightsey Darst and MN Dance Theatre's Melanie Verna share a candid, illuminating, sometimes surprising conversation on the tension between a "fetish for technique" and making room for artistry and interpretation in classical ballet.

THIS PAST DECEMBER I WENT TO SEE MINNESOTA DANCE THEATRE’S NUTCRACKER. The Nutcracker is a sentimental favorite; I don’t go expecting revelations. Melanie Verna was dancing the Sugarplum, and while I was looking forward to seeing her — Verna is an extraordinary dancer — I didn’t think she’d be at her best. Every time I’d seen Verna in a classical ballerina role in the past, she’d looked like a lesser version of herself. Her lines were still clean, her phrasing still intelligent and alive, but her usual, adventurous athleticism was muted, her sense of space shrunk in on itself. She’d looked afraid.

But that night, none of this was true. Verna danced a new Sugarplum. The role is usually an occasion for prettiness, a princess in a glass case, but Verna gave us a living queen. Maybe you’re thinking to yourself, “That doesn’t sound like a Sugarplum to me!” No: that’s the point. We’ve gotten used to the Sugarplum — the little girl heroine, Marie’s highest vision of her future life as an adult woman — being a distant figurine, lighter than air, cradled in the arms of her cavalier. But what does that have to do with growing up now? Does such a depiction offer something possible, still less desirable, for a modern girl to aspire to?

Verna, though — Verna opened a window that night, and brought a world into the stage. I still remember how she threw out one developpe faster and more boldly than I thought she should — and how she used that shock, that reckless moment, as a wake-up. She did not stay in a ballerina box; she lit the far corners of the theater. You could think about Queen Elizabeth the First, you could think about Marie Curie, Virginia Woolf; her dance seemed the inside of an exploring soul. Verna and her partner, Sam Feipel, moved together like one person, so the pas de deux became less an old-fashioned love story, less a woman supported by a man, and more a kinship between this and this, whatever you saw them becoming — ground and tree, soul and mind, study and inspiration, dark matter and light.

Interpretation on this level is extremely rare (and valuable). You’d think ballet schools would cultivate it, and certainly the best teachers try, but the truth is that ballet is in the grip of a fetish for technique that sweeps all else before it. Today’s dancers are superhuman in their high extensions, their multiple turns, their 180 degree turn-out — and the pursuit of that technique eats up time that could go to exploring artistry.

Two YouTube videos can illustrate the contrast I’m talking about. The first clip, from Anaheim Ballet, shows one photo moment after another, like highlights from a reality show. Legs! Spins! Shazam! We are seeing the Anaheim dancers in a class setting here, so it’s not fair to judge from this their interpretive abilities, but still, it seems revealing that this is the vision they choose to present. The second is a variation from Coppelia, performed by Gelsey Kirkland in 1976. Never mind how reportedly messed-up Kirkland was by this point in her life; her dancing is astonishing. The technique is there (and how), but what you see first is play. Kirkland draws you into her little world, makes you care about the most minute of weight shifts, and lets you play along with her. In Kirkland’s hands, this dance is alive, present-tense.

Verna herself is fierce on the subject of interpretation. “Ballet dancers need more acting classes, I swear to god.” She describes a technique-focused dancer: “You go out and you do your steps, and it’s beautiful and it’s great and it’s wonderful, but everyone is focused on your technique because that’s all you’re focused on. There’s no story going on inside your head, you’re not portraying the character; you’re going out and doing the steps, and that’s all [anyone] can look at, because that’s all that’s coming across.” For herself, she says, “It’s always been about the artistry first.”

So few dancers these days can do, or even try to do, what Kirkland does, and the result is that ballet’s past is in danger of becoming past indeed — history, with little to offer our present-day lives. That’s why Verna’s Sugarplum was so exciting. Like everyone else in the audience, I was riveted, thrilled. I thought I was seeing a breakthrough — and, as it turns out, I was, though not one that’s going to lead to too many more classical interpretations.

VERNA AND I WENT TO SEE the Suzanne Farrell Ballet perform at Northrop on March 12. Verna was wearing a cute cocktail dress with a boned bodice, spaghetti straps, and a short layered tulle skirt; “My tribute to ballet,” she called it. “It’s like a tutu that’s been left out in the rain,” I said. She laughed. “That’s exactly how I’ve been feeling about ballet lately,” she said. Uh-oh.

______________________________________________________

I couldn’t help wondering what the ballet girls, who turned out in hordes, found for themselves at this concert: just another chance to be that inaccessible princess, provided they add another hour to their already brutal ballet schedules, and maybe get another spin or inch out of their tiny frames?

______________________________________________________

I thought it’d be a natural to take Verna to see Farrell’s Balanchine, especially since Balanchine stressed, and Farrell was prized for, qualities that Verna shares: sense of space, athleticism, abandon. But whatever her own dancing was, Farrell seems to prefer to focus on execution in her dancers. Neat, punctual, and eager to please, her dancers bounded studiously and sincerely through the almost-camp sweetness of the pas d’action from Balanchine’s Divertimento No. 15; that beginning set the tone, and the dancers never broke through to the reckless stretch they needed to lift Agon above its classical foundation. It was Balanchine as formal genius that Farrell presented; and though Verna could appreciate it, for herself she wanted something off-balance, raw-edged, pushed. Watching the ballets, I couldn’t see a place for Verna in them either. The women’s roles showcased a feminine otherworldliness that is the last thing from Verna’s earthy strength. But that could be changed by interpretation; the elusive sylph is just a stock pose for ballerinas. Still, no wonder Verna didn’t see herself there.

I couldn’t help wondering what the ballet girls, who turned out in hordes, found for themselves at this concert: another chance to be that inaccessible princess, provided they add another hour to their already brutal ballet schedules, and maybe get another spin or inch out of their tiny frames?

Ultimately, pretty as it was, and as happy I was to see these ballets in person, Farrell’s Balanchine left me with an aftertaste of despair. When Suzanne Farrell was young, she could enter these dances, live inside them. Now, she preserves them as part of ballet’s history.

Back to Verna, though, and her wilted tutu. At 22, she’s been with MDT for seven years; she’s climbed that ladder, and now she’s feeling one of those moments of change that come over you all at once, as if the ice were breaking up under your feet. “Things start naturally dissolving, and new things appear,” she says. “I get frustrated with where I am and where I want to be. I’m incredibly ambitious, and sometimes I feel like I’m not doing what I’m supposed to be doing, and I’m looking in all directions for a change.” What change — a new company, new dance form, new country, new role? She’s not sure: “It’s so complicated. I have one opinion one day and a slightly different one the next.”

One thing is for sure: that Nutcracker may have made me dream of seeing Verna find the life that still exists, I know it, in ballet’s old chestnuts, but Verna has no dream like that herself. “I have no desire to do Odette; I have no desire to do Coppelia,” she says. She’s long known that a big classical company is not for her. Her earliest training was in Martha Graham‘s modern technique, rather than in ballet, and classical technique didn’t come easy for her. “The older I got, the more I struggled, the more I realized how good some of these kids were, how crazy and perfect their technique was, and how everybody fawned over them; I realized that I had to work my ass off in order to achieve that.” Now, she says, “I respect it, I can do it, but it doesn’t captivate my interest any longer. Plus,” she adds, “the more times I get injured, the less inclined I am to put my pointe shoes on.”

What gets Verna’s attention now? She says she’s drawn to the classically-based, yet radically contemporary, explorations of choreographers like Ohad Naharin and William Forsythe. She describes watching a Forsythe dancer’s improvisation: “I had never seen anybody move like that. Every single feeler that he had, physical or not, was activated. Every single toe was aware of where it was, and every single fingertip was specific, every single shoulder roll and head movement and eye glancing — everything was activated, everything was working together; it was just gorgeous to me. I would love to learn how to move like that. It’s just, absolutely, how I feel like I should be moving for the rest of my life — and I want to have that soon.”

Goodbye, Nutcracker. “I feel like one day,” she says, her restlessness agitating her hands, and eyes, and voice, “I’m going to hang up the pointe shoes and do some Ohad stuff, and roll on the floor, and move with my fingers — something a little more different — I don’t know.”

______________________________________________________

I can’t want musedom for Verna; she’s not a wayside flower waiting to be found, not some sleepwalker who needs waking.

______________________________________________________

WHAT DOES ONE HOPE FOR A DANCER? It’s conventional to hope that she find a great choreographer to work with, that she become a muse, like Farrell. The muse gives herself to a dance that is the choreographer’s translation of her inner essence, supposedly, but it might be just as accurate to say that the work springs from the choreographer’s continual misinterpretation of the muse, his continued failure to quite get her. To have work made for you is the highest honor in ballet, but paradoxically, the muse might be the least free of dancers, the least herself, on stage.

Introducing the second day’s program, a little tour called “The Balanchine Couple,” Farrell remembered Balanchine’s famous indifference to the fate of his ballets. He couldn’t imagine them without him, couldn’t imagine why anyone else would want to keep them alive after their time; he didn’t care, Farrell concluded, “but I care.”

Did Farrell foresee this for herself in her youth? On stage, introducing the pas de deux one after another, she was reading from a script — reading clearly and well, but not talking. She even went on and off stage with a ballerina’s processional walk.

I can’t want musedom for Verna; she’s not a wayside flower waiting to be found, not some sleepwalker who needs waking. “Having to find somebody else to bring something out in you is not at all what I want,” she says. Instead, she’s been thinking about creating her own work.

If you’re a creating artist yourself, this will sound like a no-brainer, but ballet dancers are rarely encouraged to create more than a phrase here or a flourish there; you can go through a lifetime in ballet without having a single choreographic thought. For Verna, the possibility of choreography opened only after she had to make a routine for her students. “I was forced to think about it,” she says. “And the more I thought about it, the more I liked thinking about it, and the more I wanted to pursue that.” This is very new ground for Verna, and she’s aware how much there is to explore. “I think of my friends who are musicians — they create everything from within themselves from scratch. Nobody’s telling them what to do, nobody’s telling them anything except for themselves. They’re so far ahead of me artistically because they’re giving themselves and that’s all they’re giving. And sometimes I feel like I need to do that, too: I need to create something, I need to give just myself.”

Verna fully intends to go on working with other choreographers as well, but she’s eager to explore, to try seeing dance from this new angle. “If you don’t change,” she says, “you’re doing the same thing every day, and who wants to do that?”

Whatever she does, one thing’s for sure: she won’t leave dance. “I always knew that I was a dancer from the day I stepped in a studio. It just never occurred to me to do anything else — ever! I can’t imagine my life without it. I wasn’t put on the earth to do anything else but this.”

*****

IN OTHER BALLET NEWS, I went south to see Continental Ballet Company for the first time. CBC, based in Bloomington, is one of the Twin Cities metro-area’s second-tier ballet companies. I won’t say I was pleasantly surprised by CBC, because I see CBC dancers in class, and I know they can dance. But you may be surprised to hear that you can find a very good Le Corsaire pas in Bloomington — and Paquita, and Les Sylphides, and other classical tidbits. If you’re starved for classical ballet (which you could well be, in the Twin Cities), go there.

No one at CBC offers or promises world-class interpretations, but I saw flashes of interpretive play from Mackenzie Martin, lifting the waltz from Swan Lake with her smooth musicality, and from Katherine Krieser, exploring both the steely hardness and the melting sweetness of her role in Paquita. But Krieser wasted time wincing at her own technical weaknesses, which no one in the audience would have noticed if she hadn’t. The irony of the technique fetish (which is of fairly recent date; watch Margot Fonteyn from as recently as the 1960s, and you can see how little she conforms to contemporary ideals) is that few audience members can distinguish between average and good technique, and fewer really care: the dance is the thing. I wish CBC’s dancers would realize their freedom a little more.

CBC’s leading lady, Yuki Tokuda, deserves to be taken seriously: musical, with stunning balances, she’s got the kind of steel-toed technique that looks effortless on stage. A taller frame, like Verna’s, is hardly ever this secure en pointe. Actually, I wish Tokuda felt her weight a little more, in all senses: she could roll more through demi-pointe, she could meet her partner with more tenderness, and she could show us a greater range of emotion.

Speaking of her partner, I’ve been so focused on the female dancers I forgot to mention Alexander Smirnov, who is a much stronger male dancer than you’d expect to find with such a small company, and who, more importantly, actually feels his dance, giving us a swoon-worthy Corsaire. Smirnov is reason enough to make the trek to Bloomington.

Overall, what I saw in abundance at CBC were happy dancers. These dancers, most of them past the age at which a serious classical career is an option, were so thrilled to feel the choreography and the music that only a grinch could resist them. And we are not grinches. The sense that the dancers are enjoying themselves is vital; that lifts us more than another pirouette.

I want to tell Verna that what she sees when she looks at the world of classical ballet isn’t the way things have to be; where she doesn’t see a door, she can make one. But I know these things are difficult, and for ballet dancers, even more than for the rest of us, time and energy are at a premium. Mostly, I want Verna to be happy in her dance, wherever that takes her, and wherever that takes us.

______________________________________________________

Related performance:

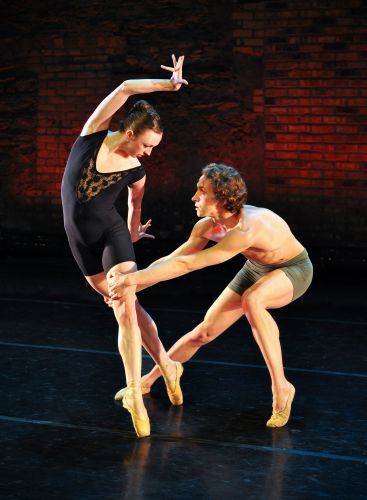

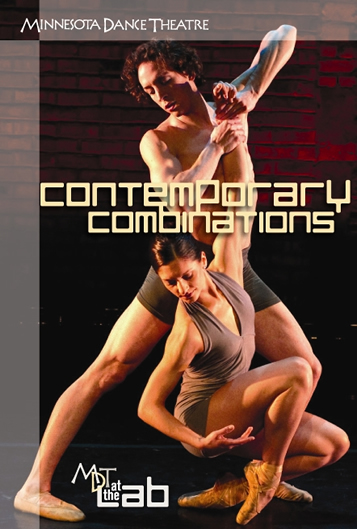

Minnesota Dance Theatre presents Contemporary Combinations, which will include the world premiere of White Jacket Only by Justin Leaf and the company’s dancers, at the Lowry Lab Theater in Minneapolis, April 16 – 25.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Originally from Tallahassee, Lightsey Darst is a poet, dance writer, and adjunct instructor at various Twin Cities colleges. Her manuscript Find the Girl has just been published by Coffee House; she has also been awarded a 2007 NEA Fellowship. She hosts the writing salon, “The Works.”