Tectonic Dissociation / Disociación Tectónica

At the conclusion of a multi-year creative process, two choreographers—based in Minneapolis and Buenos Aires—revisit the disjunctures of their collaboration, the conditions that shaped them, and the possibilities for how to meet one another

Para la versión en español ir a la página 2. >>

This interview took place on Thursday, July 20, in Buenos Aires. We met at Roma Trigo’s house, my performance voice teacher and dear friend who housed me the last few days of my stay in Argentina.

Celia and I premiered our show Friday, June 30. We had done six performances of Speziaita at that point and were preparing for our last two shows. In preparation for our finale, we wanted to have a conversation as a debrief of our multi-year collaboration. It became a space to observe our shared trajectory in relation to the structural conditions that shape each of us.

Pedra PepaWell, here we are with Celia Argüello y Pedra Pepa, La Celi y La Pepi.

Celia ArgüelloThe one and only, Cordoba Caribe.

PPI wanted to do this interview in order to share with our audiences, our friends from both sides, Minnesota and Cordoba. To be able to show a bit of our process, a bit about our contexts that have been transforming and accompanying us up until this point.

CASo how did we end up here?

PPWe met in 2014 at the American Dance Festival. I was going into my last year at Winona State and I received a work-study position to finance my summer at the festival.

CAI was turning 30 then, and I went with the Biennial of Young Arts award, the first award of choreography for my obra Villa Argüello, and through which I participated in the International Choreographer Resident program at ADF. (An obra is a performance, both a work and a play.)

PPI began to dance in the small work you developed there with other nationalities and Americanities. I ended up very excited about the way you created, the questions you were asking, how you were moving through the materials. I stayed in touch with you—we would exchange links to the works we were producing. And in 2019 I received the inaugural Jerome Hill Artist Fellowship in Dance, and I called you right away and we began to work.

We encountered each other again in Cordoba in January 2020. Your dad, Lalo, and you picked me up from the airport and we went to a magical space, Montecito, where we lived for 10 days. The founding question—donde vamos a econtrarnos?, DVAE, where will we find/meet each other?—emerged then.

CAThe question.

PPThe question.

CAI remember that what you offered was the possibility to count on a sum of money, to rent an idyllic space for movement for a few days. It was something new for me. We imagined the encounter, I researched spaces and sent them your way. This was an opportunity I hadn’t had before. I was curious to experience what would happen, seeing recordings of your performance works. I didn’t understand in artistic terms what we were meeting to do.

The first encounter was very playful, we organized ourselves around play. We established our own rules of how to organize our time and space; including space for joy and pleasure within the project, which was also something new for me, coming from the “regime” of independent theater in Buenos Aires and its conditions of production.

I noticed quickly that we did not have a reference frame in common, not even in terms of colonial European philosophical or artistic frameworks. Me coming from those European theories, that I still haven’t found in you, and me not understanding the North American references beyond contact improv and technique. In this case, North American dance could be a reference in common, but at the same time it is a reference that we do not choose to align with as artists.

In preparation for this conversation, I again asked myself what happens when you work without common references, without shared conceptual framework.

PPI remember dearly, one flower that bloomed from our residency in Fiske Menuco, in the red and yellow valleys of the moon, was: “Don’t ask the elm for pears.” It meant that we must give value to what you are able to give, what I am able to give, and to lean into that value, not wishing to move away from those realities. It meant that we played with the choreographic materials within each territory, and, well, what there is what there is.

CAExactly. The project stayed in that tension of working with what we have got and dealing with what we have not got.

PPWe came out of that rock and went to Buenos Aires pre-pandemic, rehearsing four hours a day, five days a week for a month. Exiting nature to enter the energy of the city of fury. We continued unfolding concerns, absurdities, imaginations, manifestations, premonitions.

And then the pandemic hit. The question of where will we find/meet each other intensified and flew us to Mexico—where we lived together, ate together, worked together, by the chickens and our papers, available to the work and to how we wished to organize our time and efforts.

CAIn Mexico we were rehearsing 20 hours a week at La Bodega Teatro. I remember working a lot and talking a lot, in and out of rehearsals. This period drove us towards discussions around language and movement. What is the language of the obra, of the work? It’s not the language of water, it is the language of Pedra moving as water, or water matter inside the cells of the body.

In Fiske, it was very hard, given the hostile climate and working conditions in the desert. We needed more time there. What it did bring was the tectonic language, towards Claudia Brito, who this year supported the production of Speziaita as geological advisor. Fiske brought us closer to the earth, showing with it the differences between us that appeared at the beginning.

Celia Argüello at the Red Valley of the Moon, Rio Negro, Argentina, 2022. Photo: Pedra Pepa.

Celia Argüello and Pedra Pepa, 2023. Photo: Geronimo Lagos Agüero, assisted by Azul Rosetti and Nuwanliss.

PPYeah, this last residency was very hard under those conditions. And we began to need to understand what we each needed in order to continue working on the shared project.

CAYes, the differences reappeared, in age and experience and also in questioning: what does each of us bring in relation to our own works? For me, in that last residency it became apparent we were not wanting to do the same thing. We were not asking the same questions to life, to movement, to art in general, to discourse, to politics, to the world. Even though our tacit agreement was to end in a performance, that also became our self-containment. There was an idealization of what an encounter could produce—and there, the first dissociation occurred, the first tectonic dissociation.

PPYes, and I feel that if the choice and the desire for the encounter are not in communication with the conditions of the encounter, that is where the subduction occurs. When the efforts between two tectonic plates differ, one plate squashes the other.

CAOr they break.

PPIf the efforts are the same, new territory originates, a new mountain is generated. This is called orogenesis. But on the contrary, they break.

CAYou named it, working in the measure of what is possible. Here we had two types of deliriums: the delirium that represents me, that has to do with this city and the creative delirium in which we live every day as artists in this city, imagining it as our world. And then there is your delirium that—I’m not sure what it was, and what you thought was going to happen with this encounter.

PPOf course, my delirium was feeling done with Minnesota. Done with what I was seeing, what I was experimenting with. I needed to see beyond. Minnesota is very insular—insular in what is said, what is done, what is shown, what is financed. The U.S. as a country is insular in what is seen, what is funded, what is researched, how it is researched, how it is shared, with whom, who has a voice and who doesn’t. And the America-centrism which everyone abides by.

I was searching to imagine myself outside these conditions, within which I learned dance and performance, and within which I developed and established myself as an artist. I was coming from doing some intentional work with Spanish and activism in performance, moving away from the American contexts. In 2018 I performed in the closing cabaret of a gender colloquium in Puerto Rico, where I began sharing with Latinx queer dissidents outside the U.S. mainland.

I later began to prepare to work with you. My delirium was to work in Latin America, to be with you, to see and live other ways of living, of existing, being able to share with you and your communities, to learn how you speak about art and think about art. And expose myself too, to the local deliriums of Buenos Aires. The main delirium for me is nature, it has always been nature.

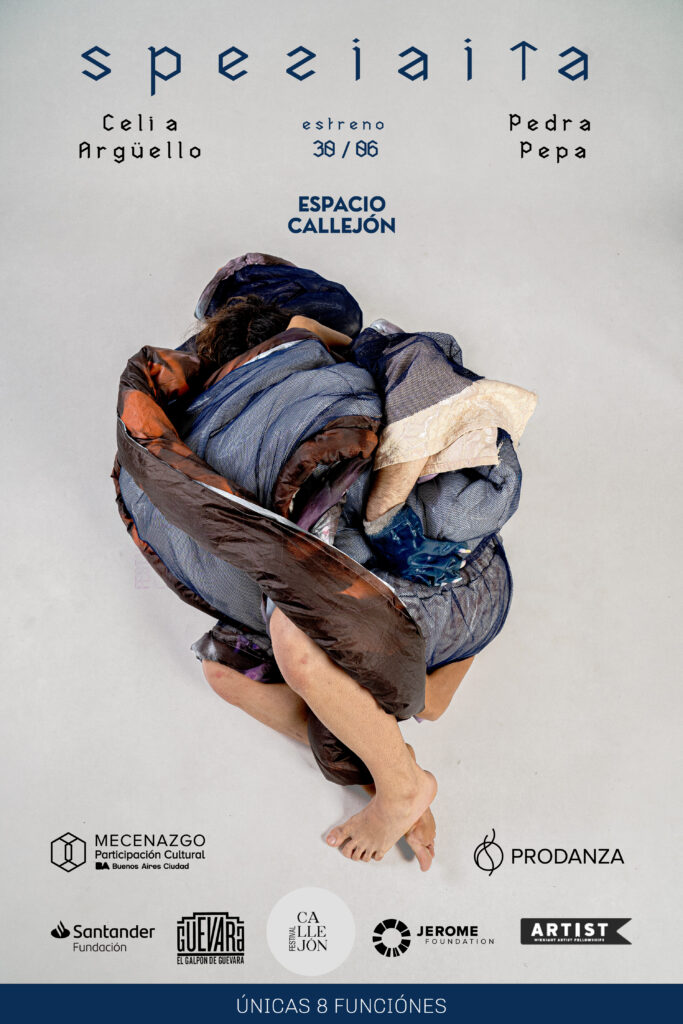

Celia Argüello and Pedra Pepa, Speziaita, 2023. Photos: Nahuel Colazzo.

Celia Argüello and Pedra Pepa, Speziaita, 2023. Photos: Nahuel Colazzo.

Celia Argüello and Pedra Pepa, Speziaita, 2023. Photos: Nahuel Colazzo.

Celia Argüello and Pedra Pepa, Speziaita, 2023. Photos: Nahuel Colazzo.

Celia Argüello and Pedra Pepa, Speziaita, 2023. Photos: Nahuel Colazzo.

CAI also think that our material conditions were at opposite ends of the continent. No? Even though we met in the same territory, our material conditions as artists, that have shaped how we think of ourselves as artists, are very different. Here we do a lot with very little, and the work is incisive in deepening the language we wish to share. Later we have the chance for our work to hold itself through time and it also elaborates an aesthetic and political way of working. Even when we are manipulating the same material in the same moment, there is an affect with the material that is very different. I ask myself today, now that we have finished our creative process, how many transformations have we lived? It would be good to do that exercise to help metabolize it.

PPTell me about how you first got started in Buenos Aires.

CAMy first performance tests happened in spaces of experimentation, spaces that still exist, where they give room to new artists so they can research and share their work. These spaces do not require application and are non-selective—that, I think, changes everything. I insist that it is matter of the affect; there are affective agreements you have the opportunity to make. The space is open for anyone who needs it. You may not need to pay, or apply, it doesn’t depend on your CV. It may be common that in some of these spaces the same people circulate always, but there are still some spaces that remain very open outside endogamic communities.

PPThe porteña thermodynamic—let’s talk a bit about Buenos Aires. (“Porteña” is what you call people from Buenos Aires, from the port city.) It catches my attention that, since coming here in 2020, developing relationships, seeing performances with you and other friends, I notice how much theater there is! Everyone is creating performance art works. And those obras continue to have seasons, and people continue to see them, and they organize themselves around performance art.

CAThere are a lot of productions. It is striking to me, because it doesn’t happen almost anywhere else in the world. I think there are 420 independent performance spaces, of all sizes. For example this home could be a theater, perhaps 20 people show up. There are a lot of spaces for production, training, research that are not financially sustained by any entity. It’s pure will of the owners and those who run them. It is incredible and it is not easily comprehensible, why we wish to create so much theater, so much dance, and in whatever way possible.

Everyone has the opportunity to create, and that, to me, has some value in terms of possibility, of accessibility. There is a self-appropriated cultural identity where one does not need the support of an authority to generate a performance. There are people, let’s say, some doñas (women of the neighborhood) that are making theater, a performance work, and their friends come over, and that is a cultural event here.

In this context, there is a lot of precarity. With that way of producing, it is difficult to achieve politics that protect us. (Currently there is active mobilization in Buenos Aires towards a National Dance Law to protect movement artists.) If everyone wishes to continue creating at all costs, then there are tensions that are interesting and sometimes irresolvable. What does it mean if we are fighting for better conditions but then everyone ends up accepting negligent work conditions? In general, we say very often we work under negligent conditions, architecturally, technically, work-wise, contractually. There exists a passion for the work and a professional neglect.

What happens in Minneapolis?

PPIn Minneapolis, there are a variety of processes that you may apply to, performance incubators. There are more of these for emerging artists, across art forms, like Naked Stages at Pillsbury House Theatre, New Works 4 Weeks at Red Eye Theater, Monkeybear’s Harmolodic Workshop, Puppet Lab at Open Eye Theatre. (Disclosure: The editor of Mn Artists is also a co-artistic director of Red Eye Theater.) If you’re selected, you have the opportunity to share with various artists. Then there are dance places that are very institutionalized, and beside that there are independent/experimental spaces, some of which have been closing. Some new platforms have emerged, like Lightning Rod, a collective of all trans/queer directors.

CAHere there are non-official trainings and workshops that last all year long.

PPLike the Libidinal Laboratory by Silvio Lang, I attended for almost four months of my stay here.

CAThose workshops are full of teachers of theater, movement, research, writing, dramaturgy. There are thousands of workshops, as there are thousands of spaces and performance works. Those places are seedling spaces of thought, for artists that begin to group and generate their own thought production.

PPIn Minnesota there could be a workshop, a summer workshop, but there is no continuous pedagogy. There are other technique classes, but besides that there are no creation classes or performance making classes. Here in Minnesota, I don’t feel a collective desire for continuous learning, taking classes outside of technique or movement improvisation. And this has effects on how much work is created and who goes to see it. We need more practice of thought, of continuous process, generating provisional communities for learning.

CASharing classes here is also a way of generating income. You perhaps train for a bit, dance in a couple of performances, and you begin to share classes, even if you didn’t have formal pedagogy training or university degrees. And that brings other spectrums of good and bad, but what interests me in terms of anti-system and anarchic thought is that one doesn’t need an authority, but one appeals to responsibility—as much as from who takes the class as to who shares the class. There are mutual responsibility agreements; it’s interesting to see the phenomenon. The performing arts are lived very much in community, it’s very hard not to be among peers.

PPDue to the specific circumstances in Minnesota, there have been formations of affinity and cultural communities, queer and BIPOC spaces. These communities lean towards introspection and connection with community, healing processes of self and the collective, reconnecting with knowledge, for example Native, anti-imperialist, anti-racist knowledge. I’m thinking of Pramila Vasudevan with PRAIRIE|CONCRETE, developing practices with plants, nature, webs of ecosystems, learning Dakota stories and teachings; or Rosy Simas with she who lives on the road to war, healing rituals of community webs, and with her 331 Space generating critical resources for artists’ processes and creation.

CA I personally believe that this is a global trend, to regain these practices within the performing arts and all other forms. I think it has to do with the state of the world and its deterioration. For example, the hyper-productivity that occurs in all cultural capitals in Argentina with independent theaters drives us to processes of production that are already formatted and rigid. It happens to me—I’ve been having a crisis in regards to that. And what did we end up creating? A performance work, an obra.

PP On another hand, when we talk about the U.S., there is a high fidelity to the base of dance in contemporary dance. Beyond those experimental and ritualistic performance spaces and practices that haven been blooming over the years locally and nationally, in regards to contemporary dance in the U.S., it is a repetition of technique steps, and that is not the case in Buenos Aires. It may happen in more commercial spaces, but in Minnesota in spaces who claim experimentation, they continue repeating choreographies from 40 years ago.

Celia Argüello and Pedra Pepa, Speziaita, 2023. Costumes: Ramiro Bailarini and None. Photos and graphic: Geronimo Lagos Agüero, photos assisted by Azul Rosetti and Nuwanliss.

Celia Argüello and Pedra Pepa, Speziaita, 2023. Costumes: Ramiro Bailarini and None. Photos and graphic: Geronimo Lagos Agüero, photos assisted by Azul Rosetti and Nuwanliss.

Celia Argüello and Pedra Pepa, Speziaita, 2023. Costumes: Ramiro Bailarini and None. Photos and graphic: Geronimo Lagos Agüero, photos assisted by Azul Rosetti and Nuwanliss.

CA Incredible. Yes, here you’ve witnessed work proximal to what we do, but there are a lot of people in that mood here, repeating choreographies. It is true, for example, that I have a lot of technical training, but in the works I directed or performed in, it’s not required for that to emerge onstage. Here we give value to research and the artist’s singularities, which are embedded in the training from the beginning.

Here, beyond the independent theater community, it’s worth naming that in official spaces and theaters that finance shows, there are continuous fights asking for independent dance to appear in those spaces—some of which I’ve participated in. Obra del demonio by Diana Szeinblum, the theater where it was performed (Teatro Colon) has 100 years as a national theater, and all sorts of languages perform there, and dance had never had its own production. In the independent theater, the support and funding are given by the state. There is little private funding. So there is somewhat of a ghost economy, sustained irregularly and unclearly and without much money.

PPThe turbulent mix of funding exists in Minnesota and the U.S., and one ends up rendering accounts to someone. Despite this, there are great funding options that support artists and processes directly, like the McKnight and Jerome Foundations.

CAHere that doesn’t exist, that you receive financing to live your life for a period of time. There are project subsidies, and later you must render accounts to the community.

PPSimilarly here, depending on the financing organization.

In Minnesota one also feels the precarity in some ways, specific to the state of affairs and contexts here. There is competitiveness, feeling that there is not enough for all, not receiving enough for the process or project. It is clear that, comparatively, the Argentinian financial crisis affects the state of dance and each artist directly, and precarity is felt every day constantly. In Minnesota, there is an inflation of the cost of living, in lesser proportion, that still generates scarcities and affects the realities of art and artists. Scarcity here is felt also through the hyper-consumption that drives us to want more and more, individualizing ourselves and perpetuating the feeling of not having enough to live.

CAI know about how you live through your performances, the classes you teach with various organizations and your fellowships over the years. But how do other artists live?

PPMost artists here have other jobs outside the art field. There are not that many dancers/choreographers who only transit in art.

CAHere we impart classes, make obras. We live off of what we want, in the myriad of art-related jobs under the same umbrella of work, be it dance or performing arts. Here, even taxes are regulated under your profession, by activity. We end up exploiting ourselves, as you see with me.

PPIn Minnesota, people work for a year or two on one performance that is shared once—one weekend or two, and that’s it. How long do performances last? Here in Buenos Aires, people research the work, they perform it, refresh it, share it, remount it, and people come back to see it. This is an example of our temporal, spatial, material relationships.

CAYes, yes.

PPSomething that we began to see in Minnesota is that these funding places stopped asking for formal productions as receipts. More process-based works were pursued.

CAHere in Buenos Aires, it would do us good to abandon the formal format of performance.

Celia Argüello at the Red Valley of the Moon, Rio Negro, Argentina, 2022. Photo: Pedra Pepa.

Celia Argüello and Pedra Pepa, 2023. Photo: Geronimo Lagos Agüero, assisted by Azul Rosetti and Nuwanliss.

PPAny last thoughts?

CAIt’s worth mentioning the value of having been able to work together through the years, accepting our differences. Accepting that we were not going to meet each other, that it just wouldn’t happen in some of those areas, but it would in some others. Learning how to support each other anyway, to lean into all that was and is there, that unstable leaning that I feel is most interesting from a movement perspective—let it be a search, conceptually, of instability, the undefinable, the illegible, the indescribable. I feel like all of this lives in our work, and people experience it when they come to see it.

We closed out the show with two sold-out performances that weekend, and I left the country the following Tuesday.

Celia and Pepa worked in collaboration through artistic residencies in three different landscapes: Cordoba and Rio Negro (Argentina) and San Francisco, Nayarit, Mexico. The collaboration between Pedra and Celia was sustained by the support from Pedra’s Jerome Hill Artist Fellowship for Choreography and the McKnight Fellowship for Choreography.

Translation note: Voice interview was conducted in Spanish, then transcribed and translated to English, edited in English, then retranslated to Spanish.

Para la versión en español ir a la página 2. >>