A Beautiful Campaign

With a foot squarely planted in the aesthetic traditions of minimalist art, Gregory Fitz uses humble materials to make spare, stark works subtly imbued with concern about climate change and runaway consumption.

Working with simple materials like home insulation, cedar board, acrylic and spray paint, Gregory Fitz makes spare and stark images with the potential to stir a sense of citizenship. With more subtlety than a waving flag or a stump speech, Fitz keeps one foot rooted in the traditions of minimalist art as aesthetic strategy to unobtrusively introduce politically fraught conversations about climate science, consumption, trash production and land conservation. Recently on view in the Kiehle Gallery at St. Cloud State University (SCSU), Fitz’s The New Normal accentuated the irony of being aware of a problem without contributing to any concerted solutions

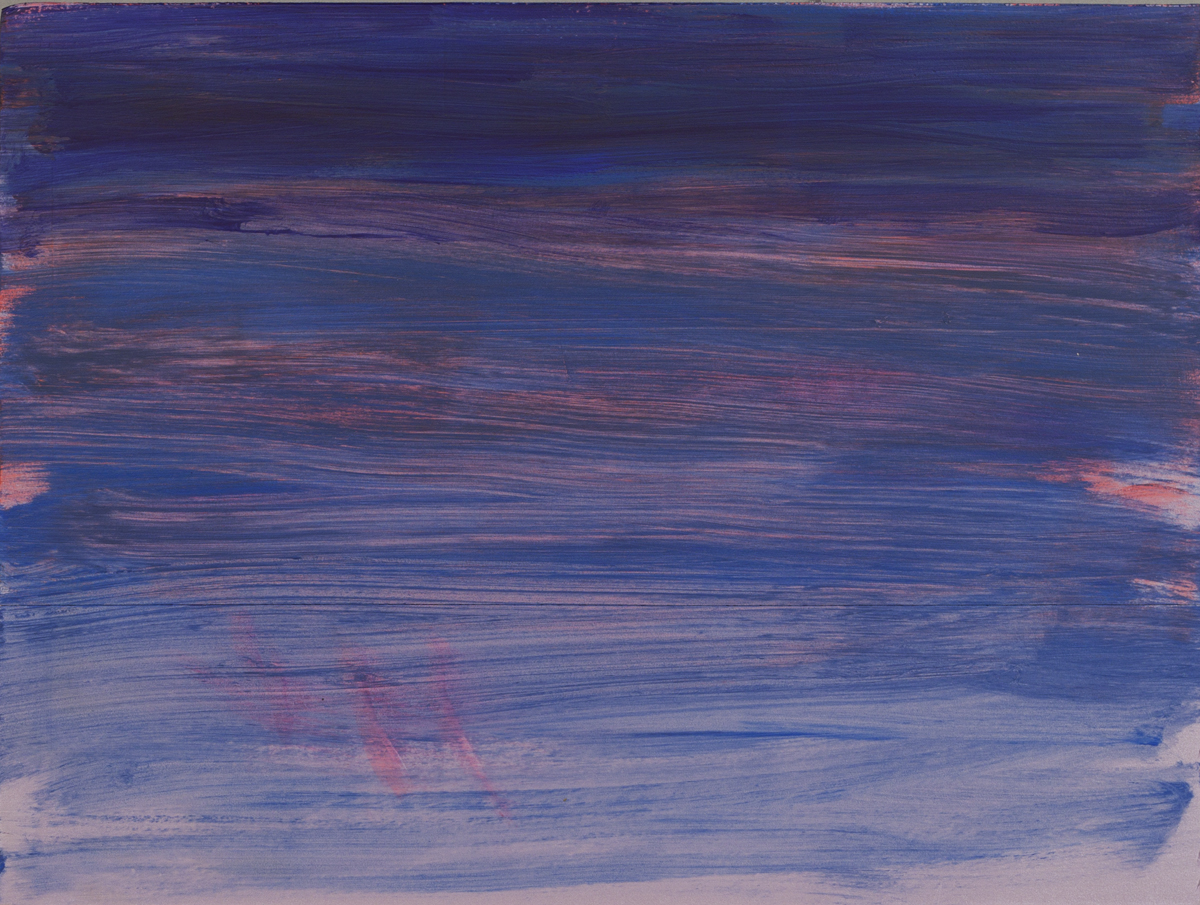

The exhibition featured about 15 new paintings from his Aurora Borealis and Sunrises/Sunsets series, and one site-specific installation, A Talisman Against Limitless Growth (Summer 2014). Aurora Borealis is marked by casual sweeps of neon aerosol paint across planks of store-bought, foil-faced foam sheathing. The Sunrise/Sunsets compositions of diluted acrylics shimmer atop rigid polystyrene foam panels, an unorthodox art material that warps along the gallery wall. The Talisman installation is a hand-built, open-faced box garlanded with one long, uncut strip of reflective ribbon. Fitz has inherited his style from the likes Robert Morris, Carl Andre, Cy Twombly and Katharina Gross, but his integration of ethics with aesthetics points to the sort of art practiced by Doris Salcedo and Olafur Eliasson.

Eliasson’s Ice Watch and Salcedo’s Thou-less, for example, each pitch challenging emotions and calls for response through the familiar language of pure formal play. The old-hat styles of the high modernists, when left alone, lead to the sort of artworks that endlessly refer back to themselves in cultural whirlpools that fetch prices like stocks and bonds. But in the hands of Eliasson and Salcedo the comfort of simple, beautiful objects and images allows inroads to conversations that, if presented less palatably, might be too didactic or hamfisted to digest.

Fitz likewise handles audiences with a light, almost seductive sensibility. At first blush, the works in The New Normal do read as reissues of those old hats, yet they also stand as expressions of the artist’s progressive political stance. Fitz could have kept his works untitled, leaving them alone in their lush and haptic vibrancy, but instead he gave audiences the option to add consideration to the relationship between Fitz’ use of non-biodegradable materials and slapdash representations of our deteriorating earth.

During a public discussion held recently at SCSU, Fitz explained that he began designing Talisman as an homage to the simple structure and utility of his neighbor’s raised garden bed. Sometime later while visiting Dave’s BrewFarm he noticed a shimmering material draped over a pond of ducklings: like a force-field, Bird-B-Gone sheets protect birds from colliding with big panes of glass and small animals from predators. Fitz also noted that the negativity which pervaded the summer news coverage of 2014 inspired him to to make an object of reflection and recognition. Delivered to viewers first in the guise of innocuous formalism, Talisman has the potential to become a memorial to violence and a humble beacon of hope.

In the Kiehle Gallery, audiences could refer to simple list of works in a binder, but no wall texts. This aloofness from detail keeps Fitz’s work from slipping into didacticism or political advocacy. To be sure, Fitz sees himself as an artist first and an activist second. During a recent interview, he described how he developed ideas for the Aurora Borealis and Sunrises/Sunsets series in the reverse order as would a designer working for a client. Instead of beginning with the message and then adding the formal gestures of narrative imagery, Fitz first chose polystyrene for its shining and blue and pink surfaces. Only after his formal experimentations with the stuff did he begin to examine his own “participation with our culture of consumption.” Given the non-biodegradability of his paintings’ supports and his love for those old-hat styles, he asked himself, “what work are my objects are doing?” Despite changing his tack to make pieces that refer to our threadbare environment, he acknowledges that his objects make for “pathetic activism. They’re not doing enough direct work. They’re doing the work of art, which is to be a byproduct and celebration of consciousness.” Even so, Fitz’s work challenges audiences with an authentic sense of urgency beneath the familiar, pretty styles of minimalist abstraction.

In a recent article written for Mn Artists, Christina Schmid responded to a public conversation held as part of Michael Kareken’s Parts exhibition at Burnet Gallery. When someone in the crowd suggested that his paintings of demolished cars read like political commentary, Kareken demurred and stated that “the political makes the work too one-dimensional.” For Schmid, if a given artwork sits on a soapbox there is a risk that its “beauty might be reduced to mere propaganda.” But the two are not mutually exclusive. Propaganda can be beautiful. The word carries the weight of political coercion, but when understood as a principle of design, propaganda is no different than advertising. The use of aesthetics is a strategy to communicate a message, whether it’s deceptive, offensive, or meaningful.

Fitz’s use of aesthetics can affect our senses or even deliver us to sublime meditation, but his message, like all good propaganda, has the potential to alter our worldview. The CIA used this technique for cultural diplomacy during the Cold War, and Fitz and his fellow minimalists and color-field painters inherited their commitment to formalism from Bolshevik sympathizers who used concise and simplified images in their propaganda campaigns for a new society. Fitz may not be a revolutionary, but The New Normal is his campaign.

Related information:

See more of Gregory Fitz’s work online at www.gregoryfitz.net. He has a solo exhibition coming up at Nemeth Art Center in Park Rapids, Minn. later this year.

Nathan R.P. Young co-directs The Third Place Gallery with Wing Huie, and works as archivist and director of sales with Korab Image. Find him on Twitter: @nrp_y.