Ghost Pines: The Haunted Forests of a Machine Learning Dataset

Spinning climate grief into speculative forests in conversation with Ben Moren’s Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40

It is October 2011; I am 20 years old and I am watching my classmate draw pine trees.

We’re in life drawing class, but the figure model didn’t show that morning and our professor tells us instead to practice gestural drawing on any subject we’d like. The room is dusty and smells like decades of art classes: paper, graphite, charcoal, the wood of easels and chairs. A blank newsprint pad sits in front of me, lit by the slanted gold of late afternoon finding the third floor. The air conditioning is straining to keep up with the Texas heat and a fly beats against the window, competing with the scratch-scratch of charcoal on paper and the taps of my professor’s shoes as she circles the room.

My classmate pulls her hand up and down on the page. A practiced line. A graceful arc. The shape of the tree, the needles, then the bark. Straight trees, and tall, but stubbier than you might expect, with cropped tops. She stops, looks at the page, then turns it to a fresh sheet. Starts drawing another pine tree. I watch her do this a dozen times before my teacher comes to stand pointedly behind me and my own blank paper, and with effort I turn my attention to my own work.

The Lost Pines of Bastrop have been on fire for one month.

You can see the smoke to the east of town, easily visible from the university where I take classes—can smell it when the wind blows west. We emerge blinking out of the classroom into the filtered wildfire sun. I am always religious about washing my hands, my arms, my face, anywhere the charcoal dust could have left a streak. It is the first time I can remember being this tidy; I used to wear the markings of art student with no small amount of pride.

Bastrop is only a half hour east of Austin; it is a sleepy town tucked away into a fragment of loblolly pines, genetically distinct from their closest neighbors a few hundred miles away in Arkansas. Something about the out-of-place pine trees, the old downtown that spans both sides of the Colorado river, the ranch trucks and the retired hippies makes Bastrop feel more like a mountain town than small-town Texas. It is comfortable and charming, the kind of place where kids ride bikes down Main Street.

I would, years later, find out that this classmate was from Bastrop; she was drawing the pine tree that used to grow in her front yard. Both the tree and the house had burned to the ground three weeks before that drawing class, along with everything she owned.1

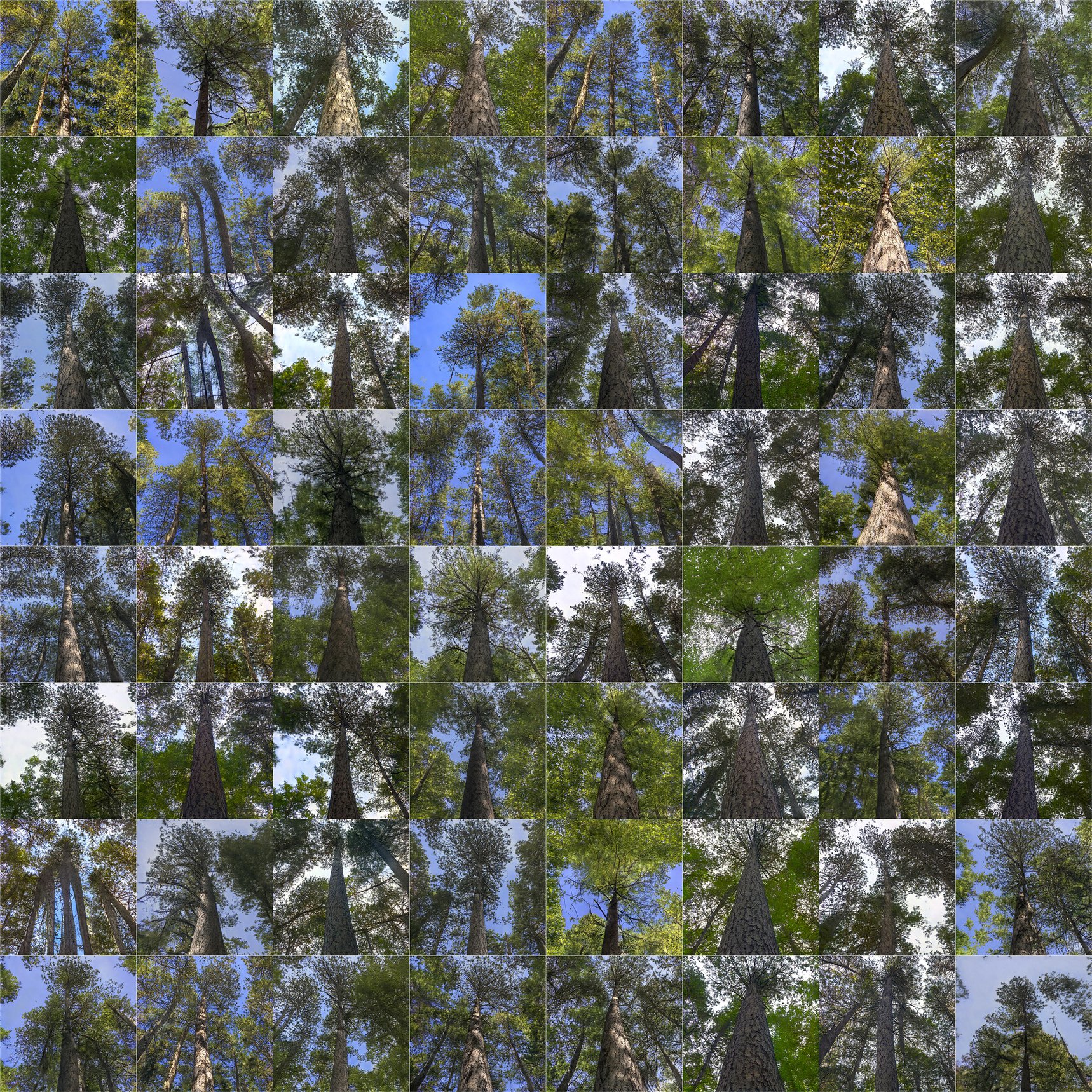

Ben Moren, Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Ben Moren, Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Ben Moren, Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Ben Moren, Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Ben Moren, Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

The fire is officially declared contained on October 10, 2011, but the damage has been done: 34,356 acres of pines, 1,693 homes, 4 human lives.

In these last few years of rampant, constant wildfire summers, these kinds of numbers have become a refrain. Even as I write this, the western half of North America is doing this morbid math: how many towns obliterated this year? How many trees, acres, homes, lives? We’re also asking the practical, almost everyday questions that come along with these numbers: did we remember to order N95 masks? Did we test the air filters? What’s Accuweather say? Is it safe to let the dog out?

I remember the mood in the classroom that October, as we tried to draw from life and ignore the death happening right outside, even as the smoke entered the ventilation system. It was a mix of all of these things: What will be left standing? Did I remember to pack a lunch? I hear the fire jumped the river again. Ah hell, I forgot to prep my presentation.

Charcoal is made by burning wood at high temperatures in an oxygen-free environment. Grape vine and willow branches are common, but so is spindlewood and elm. Some charcoals are made of a variety of woods, pressed and bonded after their carbonization; others are sold as straight little twigs, preserved as they were grown. On these, if you look close, you can see the whirls where the leaves once attached.2

I bought my charcoal from the University Art Supply store. They had a whole charcoal and graphite display, each piece wrapped in tissue paper and sorted by hardness. You could buy a metal pencil-shaped tool to hold them if you disliked the mess, but I always ended up using my fingers.

After the fire, I avoided Bastrop for months but eventually some out-of-town errand sent me down that highway. I could see the black spires of the burned trees rising in the distance, all the underbrush and branches burned away with just the cathedral-steeple trunks standing ram-rod straight into the sky. They seemed taller like that that, out of context—like masts of ships, telephone poles, railroad ties on end—until I realized that they were of course all of those things, also, or that all of those things were once pine trees.

In Bastrop, I stopped the car. I got out, touched the ground. My fingers came up black, covered in charcoal dust. The whole earth shimmered and sparkled in the sun. I picked up a few little sticks, thinking, I don’t know, maybe I’d draw with them or something. Later, I realized I couldn’t know where they’d come from: a tree standing in a front yard, a telephone pole, or someone’s house—which in Bastrop were also all made of pine.

I put the pieces outside.

In March of last year, 2021, I was asked to write this essay to accompany Ben Moren’s Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, a neural-network photography project based on the red and white pines of Minnesota’s Lost 40 scenic natural area.

Specifically, I was asked to talk about the more technical elements of the work, how generative adversarial networks (GANs) construct images, how Ben’s original photographs of the forest were worked into the network, how it was trained to recreate the patterns of red pine, white pine, produce its believable (if occasionally surprising) photographs of unreal pine trees.

I tried to write that essay, I really did. Instead, I kept drifting towards Bastrop—the only Lost Pines I ever knew. The Bastrop pines are a disjunct population, left stranded in Central Texas during the last ice age as the forest withdrew its range north and eastward.3 The Lost 40 are also a fragment of old-growth forest, a relic from another time. Unlike the loblolly of Bastrop, however, the red and white pines are more recent orphans; they were left standing when the state was otherwise clear-cut in the 1800s. This was, I’m told, because of a mapping error that labeled the stand of trees as underwater.4

It is August of 2021 and I’m driving through Bastrop on my way from Galveston—where I’d been living—to Austin, where my family still is. Next month it’ll be 10 years since the fire.

The trees are coming back (partly through no small effort of tens of thousands of volunteers, myself included) but they’re mixed deciduous—no more loblolly pine than Central Texas’ more standard varieties of juniper, live oak, mesquite, and elm.

I pull my car over to the side of the road to get out and smell the air, which is bright and spring-like. It’s been rainy this summer and everything is green, even in August. I bend to touch the ground, which is no longer coated in charcoal; my fingers come up wet and earthy rather than shimmery and black. On a whim, I open the folder of neural network created images that Ben sent me, full-screen one on my phone and hold it arms-length away from my body and into the air.

They’re not the same pine trees, but a dense square of green floats against the blue sky and I can sort of squint my eyes and see it; the red and white pines of the Lost 40 pictured in Ben’s work become the loblolly pines of my childhood, and as I swivel the phone around I get the distinct and dizzying feeling that I am cutting through time, making a little peekhole into a world of ghosts.

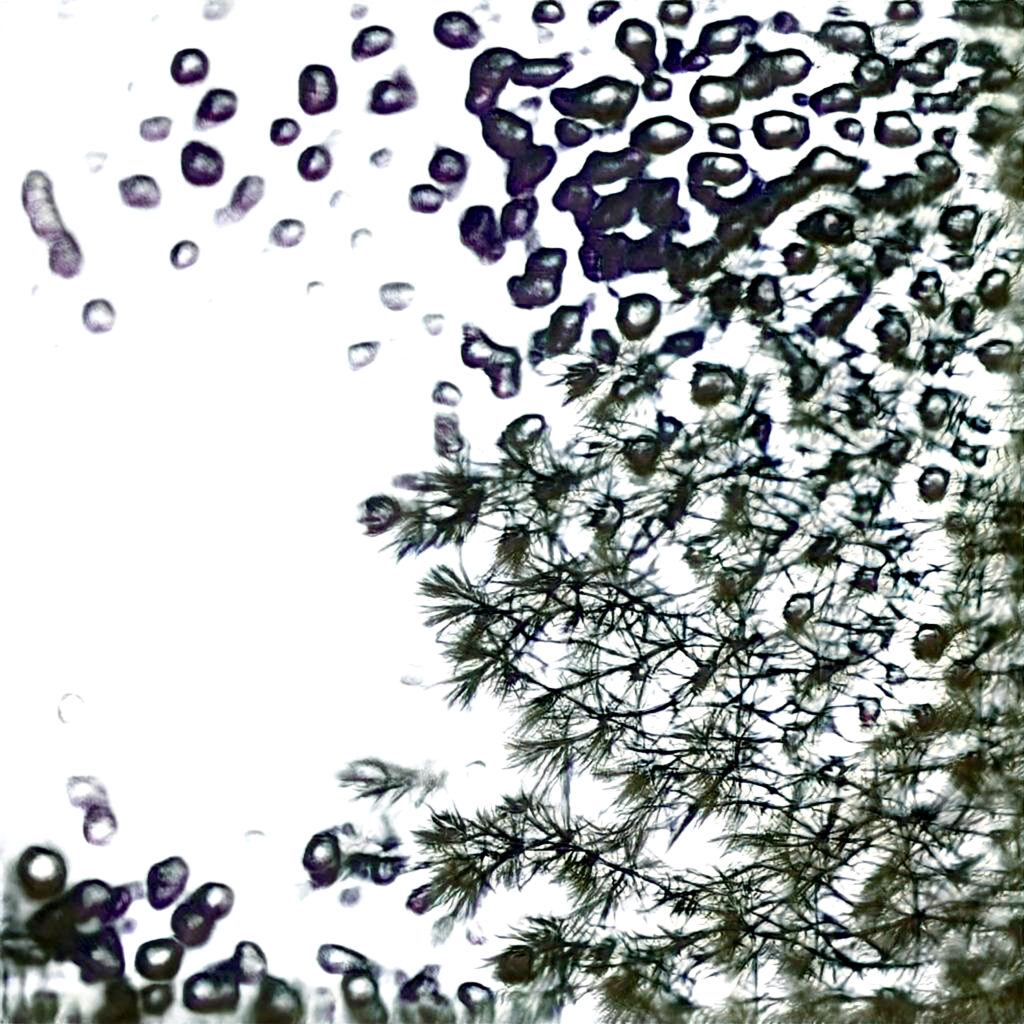

The imaginary pines that have sat for months now in my inbox were made with StyleGAN2, a GAN architecture that is particularly good at adapting to—and generating—specific types of images. To summon the trees, Ben took an existing StyleGAN model, then narrowed its focus; first onto other kinds of forests (aspen trees, quaking bogs) and then finally refined on the images that Ben himself took of the Lost 40 SNA: datasets of vistas, individual trees, and closeups of needles and of bark.

Ben Moren, Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Ben Moren, Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Ben Moren, Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Ben Moren, Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Ben Moren, Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Before the GAN only knew pine trees, it knew lots of things: all the faces, dogs, buildings, cars, landscapes, paintings, and flowers of any one of the myriad “general GAN training datasets” you can download off sites like Github. These images are deeply buried now under the pine, but they still exist in the model; the ghosts of millions of objects echo in how the GAN constructs patterns or recognizes edges, even the edges of pine needles.5

I am reminded of the bonded charcoal sold in the art store display case, all neat and uniform in its tissue paper; how it is almost impossible to tell what the charcoal was, and how because of this you never pause to think—was this once a house?

When Ben and I spoke about Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, he described the project as an attempt to digitally re-grow the forest from fragmentary data, the images acting as a kind of preservation through simulation.

Climate collapse threatens the Lost 40 SNA, just like it threatens every fragment habitat already pushed to the limits of what it can survive. Without major CO2 emission reductions climate scientists predict that much of Minnesota will shift to a prairie biome within 50 years.6

Trained on images of the forest in knowing anticipation of its loss, the fossil here precedes the body, making a shape a felled tree can fall into. They’re beautiful images, truly, mysterious and compelling. But they are also deeply sad, in the way a eulogy is always beholden to the poverty of recreation—how an image created of a subject that is gone, or will soon be gone, can never replace what is lost. How it can only remind us that it once lived.

For a few years, the loblolly pine had the dubious honor of being the longest genome ever sequenced, containing 22.18 billion base pairs, seven times longer than the human genome.7

The loblolly pine genome is a 20.15 Gb text file, several times bigger than the photographic dataset that Ben used to train the GANs. You can open it up and stare at the series of letters that make up the purest essence of loblolly pine, the genetic code for how the seed unfurls into a giant that produces, in time, more seeds. Everything is there, I’m told; everything a tree needs to become a tree, instructions comprehensible to itself in an innate, fundamental way.

I am looking at the file. I am trying to imagine in it the insects that chew the leaves, the squirrels that live up top, the bacteria that move under the bark, the smell, the wind. I am trying to see between the letters to the snap of the twigs and the rain running rivers down the trunks and the dense microbial network that connects tree root to tree root in a constant, swelling kind of chemical communication about pests, rain, drought, fire.

Ben Moren, Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Ben Moren, Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Ben Moren, Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Ben Moren, Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Ben Moren, Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

I can’t do it. I have a miracle open on my computer and I feel nothing. Instead, I find myself wondering what happened to the newsprint pad from my life drawing class, the one full of pine trees. Did it get recycled like so many of the year’s student sketches? Become, like my own newsprint pads, fire starters in the winter?

I imagine the drawings of the pine trees—really a single pine, in duplicate, from 100 angles—torn out of the binding and pinned to the walls, circling the room until standing inside of it feels like being in the forest. And to the simplifying eye of science and fire, would you not be in the forest? In a pine-framed room, sheeted in paper, covered in charcoal. The hum of the electrical becomes the shh-shh of the needles in the wind. The termites work as dutifully on the walls as they would on a stump. I am in a clearing in a forest. I am standing in the middle of a grove.

In Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold wrote; “One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds.”8

Well, here is the world of wounds—but I’ve never felt less alone. They are evident everywhere, across all things; they are, in fact, just about all I can think about. They are what I discuss with my parents on the phone, with my neighbors when they stop by. The wounds are the subject of major climate reports and “something must be done!” tweets and, on more than one occasion, an afternoon cry.

We should not see these wounds so profoundly, shouldn’t have to say, “Summer is hotter this year,” every year. Shouldn’t have to write the eulogy to the forest before it is gone, should not have to draw pictures of the memory of a tree out of the dead body of a pine. Even as we plant the new seedlings in the scorched earth, put our bodies in front of the pipeline construction, dig firebreaks around our homes, we think—it shouldn’t have to be like this.

And some of it won’t be like this. The Lost 40 pine forest that is the subject of Ben’s speculative photographic work is not gone, despite its extant eulogy. There is no guarantee that the felled tree will fit its fossil. We can both mourn what is already gone and lay in front of the logging truck. Miss the way summers once were and picket the Governor’s mansion. Remember a tree, and know that another one can grow there.

We’ll have to do both; learning to draw the world of wounds is not enough. Looking again at Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40, I realize these images could be as much in promise as they are in remembrance; they are not necessarily an echo of what was or will be lost, but maybe also a vision of what will come. Wild, tall pines; rough bark, straight green needles; a whole forest, rising, clarifying out of the mass, becoming so much more than their photographs—alive.

Reference Ecosystem: Lost 40 was presented as part of the MCAD Faculty Sabbatical Exhibition, January 18–February 26, 2022, Minneapolis College of Art and Design.

A print publication is forthcoming. For pre-order information, visit: http://benmoren.com/preorder