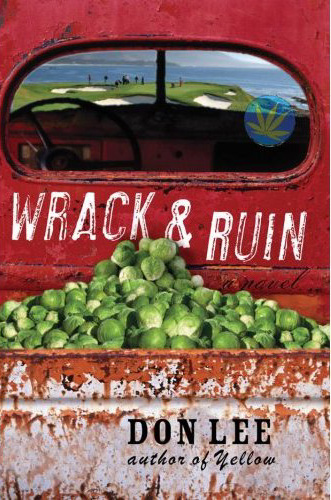

Wise Fool: Inside Don Lee’s New Farce “Wrack and Ruin”

Writer Shannon Gibney gets the story behind acclaimed author Don Lee's new novel "Wrack and Ruin," and she gives her take on the surprisingly substantial reflections on urban sprawl, race, and identity to be found in his farcical tale.

WRITER DON LEE WAS THE LAST PERSON who thought he would ever find himself embroiled in a farcical flight of Brussels-sprouts-farming fancy. But thats exactly the storyline you’ll find in Wrack and Ruin (Norton, 2008), Lees newest novelalong with diabolical property development schemes, radical animal rights terrorism, and a kung fu odyssey of filmic proportions. A creative writing professor at Macalester College in St. Paul, Lee was shocked by what emerged from his consciousness as he began his third book. I did not plan for it to be either a comedy or a farce, he said. I wrote the first chapter, and these things were just popping up. I thought, Oh shit! How am I going to do this?

When I think of the structure of this novel, I think that it’s more than just a comedy; its actually a farce [with elements of drama], Lee continued. You have this random sequence of outlandish stuff happening. But if youre going to start out so high, youve got to maintain it, or even top yourself, all the way. I thought, Theres no way Im going to be able to maintain this for 300 pages. But I just went with it, and the story kept on going. I was really kind of surprised.

Lees got good reason to be surprised at the capers that fill this novel; his first two books, Yellow (Norton, 2001) and Country of Origin (Norton, 2004), proceed with a much more somber tone. Wrack and Ruin is, well, maniacal in comparison. Take this excerpt from the beginning of the novel, when Woody Song (protagonist Lyndon Songs scheming Hollywood producer brother) finds that Yi Ling Ling (the washed-up kung fu star of his latest film project) has roundhouse kicked Lyndon unconscious in his own house: In the end, Woody had to bring her [Ling Ling] with him to Rosarita Bay. He was afraid to leave her in the city. God knew what kind of trouble she would get into on her own over the weekend, and he tried to convince himself that perhaps the delay was fortuitous. He might be able to dry her out a little, rein her in a monumental delusion, he realized, when he returned to Lyndons house and saw his brother unconscious on the floor, his hands and ankles hog-tied.

And the novel goes on from there in a seemingly endless (yet still engaging) series of absurdities that bring the huge cast of characters to a strange kind of resolution by Wrack and Ruins end. As farcical as the story is, the books ideas are decidedly not flip. In addition to musings on the environmental tensions accompanying encroaching land development schemes, according to Lee, the themes of his story are ultimately about art and about how to live a sane life as an artist, where you keep your integrity.” He explains that sections of the novel address the plight of the career artist: “[over time] these artists become obsolete in their field, and I’m interested in how they deal with that how to get beyond the standard barometers of success; what does it mean to them to actually make art?” Each of Wrack and Ruins characters is embroiled in a deep negotiation about the price and role of art in their lives, but Lee manages to imbue these inquiries with both intelligence and humor. His take on the subject matter is especially refreshing given the ease with which such books can slip into self-congratulation.

Another serious current running through Lee’s playful story involves the mythology of cultural and racial purity. Characters converge with and upon each othersome are Asian American, others Latino, some White, and still others of mixed ancestrybut none of them successfully stakes out a static, permanent “ethnic” identity. In this regard, Lee’s story represents a departure from the ideas of prominent Asian American writers like Frank Chin, who suggest that Asian American writers should write primarily from stories central to Asian cultures. Lee says, What Im not interested in doing is rehashing whats been done already. [Dalton Lee], the film director in the book, talks about this: he doesnt want to do three generations of immigrant stories or interracial love stories, or cultural misunderstandings stories. Im just not interested in that.

Lees orientation towards aesthetic exploration and border-crossing are displayed in his sometimes playful, sometimes reverent prose: There was a fat person inside Woody, a person who was tired of being oppressed and denied, a person who wanted Woody to stop working so hard and accept the inevitable, that he wasnt meant to be skinny or cut or buffed, he was meant to be pudgy, a little roly-poly. He was meant to have a neck hump and man breasts. He was meant to have a neck hump and static-abrading thighs, loose flab quivering beneath his flesh, gelatinous blubber and tissue and lard shifting and heaving in pendulous slabs. Indeed.

Halfway through reading Wrack and Ruin, the thought that came to me was, Thank God for funny writers. The most effective humor encompasses more than simply being funny; and it follows that the funniest books are also often nuanced philosophical meditations, mirrors for the absurdity of our modern existence. In just this way, and in so many more, Wrack and Ruin delivers.

About the writer: Shannon Gibney is a writer who lives in Minneapolis.

Catch Don Lee reading from Wrack and Ruin Wednesday, April 30, at 7:30 pm, at the Barnes & Noble Galleria Shopping Center, 3225 W. 69th in Edina.

About the author: Don Lee has received an O. Henry Award and a Pushcart Prize, and his stories have been published in The Kenyon Review, GQ, New England Review, The North American Review, The Gettysburg Review, Bamboo Ridge, Manoa, American Short Fiction, Glimmer Train, Charlie Chan Is Dead 2, Screaming Monkeys, Narrative, and elsewhere. His book reviews and essays have appeared in The Boston Globe, Harvard Review, Agni, Boston magazine, The Village Voice, and other magazines. He has received fellowships from the Massachusetts Cultural Council and the St. Botolph Club Foundation. He currently lives in Saint Paul, Minnesota. From 1988 to 2007, he was the editor of the literary journal Ploughshares. In the fall of 2007, he began teaching creative writing as an associate professor at Macalester College.