For Dance, a Discipline, with Language

Making friction at the edge of dance: on categories and control, the expansive potential of language, and discipline as anti-object

1.

A friend of a friend leans on the bar and asks me: So…why dance? I take a breath and shout, BECAUSE IT’S EVERYTHING IN THE WORLD, IT’S PERSONAL AND SOCIAL AND INTELLECTUAL AND INTUITIVE AND PRECISE AND ANARCHIC AND PAST AND PRESENT AND FUTURE ALL AT THE SAME TIME and I run out the front door and into the night.

2.

When I speak with someone who makes exhibitions or plays or something else, I know that I am from dance. It’s my passport; it marks me and it takes me everywhere. When I make language I am making dance and I am never outside of it. I am from dance because I am also speaking to dance.

I have an origin in something that is categorically dance, with spandex and stretches and learning to make windows so that everyone can be seen in their rows. I have strayed far from those forms but I remain in dance because I was lucky enough to learn that dance is the most expansive methodology there is.

Dance not as an end point, but as a way of moving and being in time. Dance not as a discrete object, but as a particle and a wave. Dance not as a what, but as a how. I won’t reduce dance itself to a singular object, because I have learned from dance how to refuse the conditions of objecthood—to push back, to come apart, to keep going despite. Most of all, dance as fundamentally and forever unknowable.

3.

[I am center stage, speaking into a microphone.] I am going to talk to you about the edges of dance. With all of this going on [gestures to the outside, right now, for so long] I don’t know if the question seems truly urgent, if you take it at face value.

What is dance? Haven’t we been here before, haven’t we covered this? Shouldn’t we just focus on making our work, whatever we want to call it? Right now the mood is anti-discipline: fuck the labels, don’t pin me down. Maybe you don’t find conflict here but I feel like I keep running into this wall. Voices drop judgments all the time. Well, you know, it’s not really dance, it’s— The object is placed off to the side. This is where I get interested.

The edge I hit most often in dance is language.

In this field, you can run into many different edges, particularly those related to body type, race, gender, class, empire, culture, training, commodity, so many hierarchies and ossifications and exclusions. In the last few years, many of the instances in which I’ve experienced this classifying move myself had to do with bringing text into the frame of dance.

My facility with language is a type of inheritance. My insistence on using it in dance means I’m facing the field at an angle. It feels like one of the characteristics inherent to my body, but it’s also a pose I strike over and over. I return to it because it’s complex.

[Drop voice.] Stay with me. I would like to propose that the particular choreography of running into this particular wall—the approach, the velocity, the proximity, the texture, the reverb, the observation, the repetition—has something enduring to say to us about power and how to be with it.

4.

Dancers tend to bristle at language because of the devaluation of the body and elevation of the mind in Western culture, a split that associates whiteness and maleness with logic and power and objectivity. Language is often reductive, prescriptive, and coercive. Many dancers only write about their work when they have to, for grants.

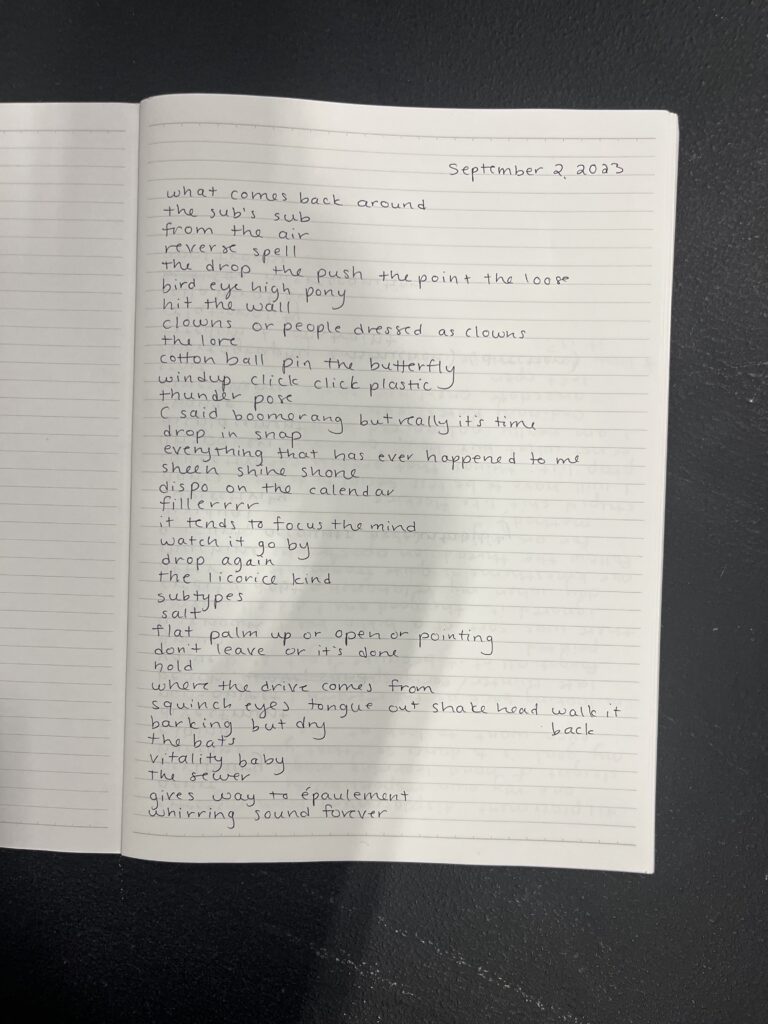

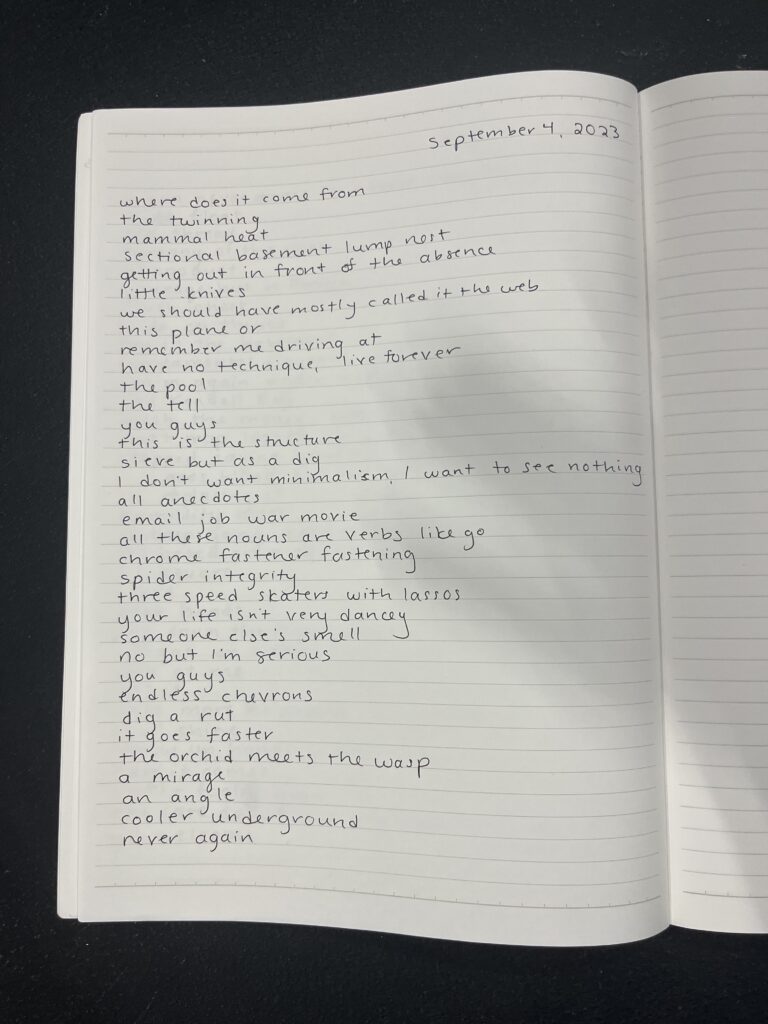

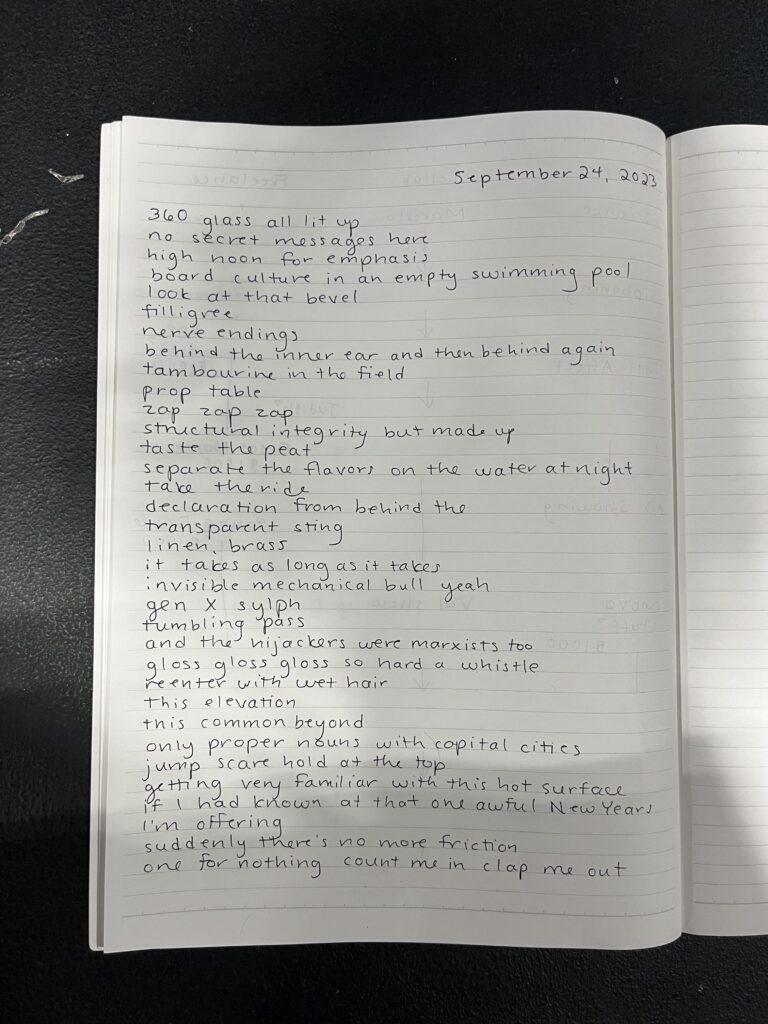

But dance is not without language. If you spend time with dance, you will be awash in language. In the rehearsal room you will hear a proliferation of language, which is often idiosyncratic, everyday, concrete, poetic, punchy, hilarious. This language arises out of the body, out of the camaraderie, out of what the mouth blurts out when you’re trying to explain what you can’t really explain.

This language is trying over and over to get to somewhere that we will never arrive, so the attempts keep coming. It’s always on the tip of the tongue. It’s the words that tumble out of your mouth when you are almost desperate. Often it’s: not ___, but almost— And we keep it moving. Oh! Yeah, no. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Dance language is hanging in the air between us. Dance language is wringing your hands. The whole field is a flowering of communal dialects, born out of a time and place and bodies in the room together. You could call it a shorthand or a practicality or a means to an end—but what is vocabulary, anyway?

5.

S is a dancer who has created her first museum exhibition. At the artist talk, this discipline question is the banner hanging over the room. A exclaims: But we’re choreographers and you’re a choreographer and so anything you do is choreography! There are scattered cheers in the audience. The panelists continue to insist that a dancer can bring objects into any frame and it’s still dance.

I tend to agree, though I’m suspicious that it could be understood in terms of credentialism. Like: I have trained in dance, I have won awards for dance, the discipline claimed me and therefore I earned my freedom to make whatever. Or to be a choreographer, is that ontological? Is it who you are or what you do?

A decade ago, I was in a feedback showing with a mix of dance and theater artists, and we were running late. As we approached the scheduled end time, E, a dancer, got up to leave, and the theater artist facilitator, M, stopped him. I remember this moment because they both took it as self-evident: the dancer that we would stick to the schedule, the theater artist that we would stay until we were finished. The theater people expected to stay because when they’re in rehearsal, they devote their whole evening to it and the actors are expected to take care of their own prep work on their own time. Dancers, invariably, are scheduled to the hilt, with laughably segmented blocks on the calendar—but when your body is present, you’re fully present. This dynamic can manifest in many different ways, but it speaks to how we absorb the structures and economies of our art forms, how we internalize and live by them.

I’m more interested in thinking through discipline like this, the assumptions we hold in our bodies, how our habits and movements and relations have been shaped by the spaces we have inhabited, the organizations of time and value that we unwittingly repeat. You know—the choreography.

Once I showed a video work sample to a program officer for a dance fellowship, a piece with a lot of spoken text, and offhand she said: Oh, so it’s really more theater. Another program officer, after I carefully explained that I contextualize writing as a choreographic practice so I would like to submit a writing work sample, responded with bewilderment: But why would you do that? There are far more harmful exclusions happening in the realm of funding, and it’s far too easy to complain about—but this is instructive because sometimes you learn the shape of the room by running into the wall. These ideas shape how resources are allocated, which work is visible, how you conceive of yourself, and what can even be made.

6.

K writes: Discipline is empire.

There is a reason that the word for categories also means control. Dividing knowledge into separate domains puts the world into enclosures, which forecloses other ways of thinking. Dividing things into types limits their horizons, how they may act, what they are allowed to do. Classifying bodies into different types, and ranking them in hierarchy, forms the justification for colonialism and everything it has wrought. Through discipline, all of this is naturalized and normalized, making these offhand comments on the nature of things all the more insidious. When it operates at the level of assumption, you know they’ve already won.

7.

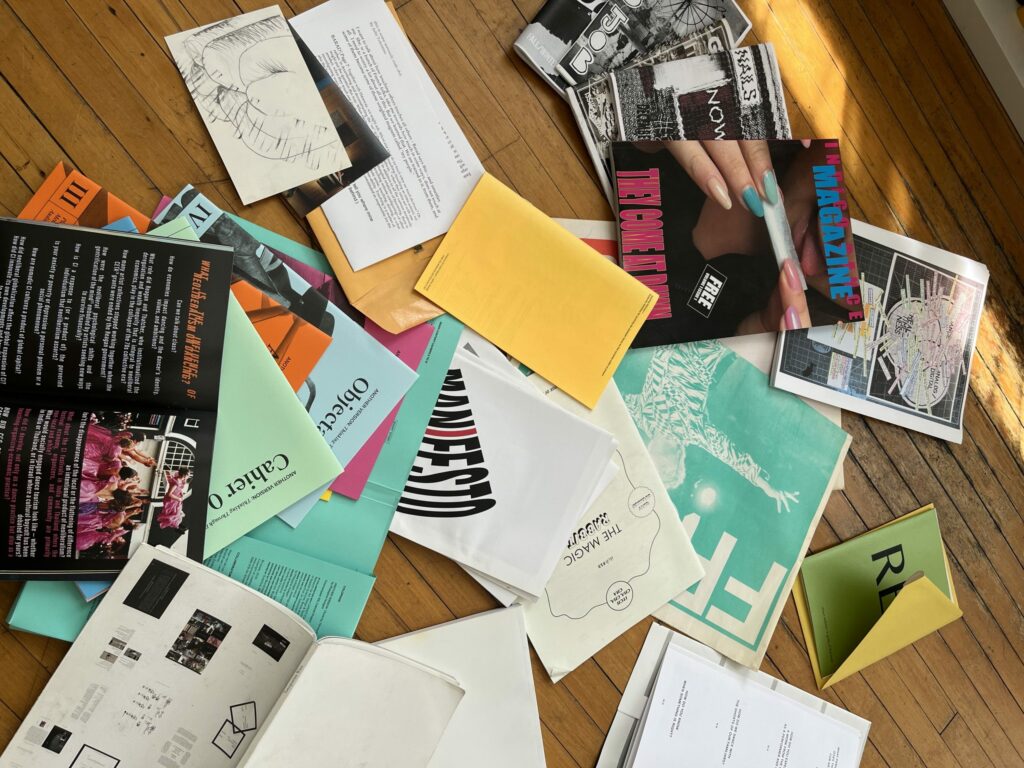

[Copy paste this text into another doc. Delete all the numbers at the beginning of each section. Then put a page breaks in between each one, reformat the document, print it into a paper book, make a few copies, give them to people you do or don’t like, take one and tear the pages out and build a small booth from some 2x4s and enclose it in plastic and turn a fan on and then get inside and let the pages blow around you (like J did once but with cash).]

8.

Several years ago in Minneapolis, M, a dance curator, teamed up with R, an adult dance student who worked in marketing, in a joint effort to “rebrand dance”—a sort of audience development project for the field at large. They hosted a brainstorm session, and I sat in a studio with a group of dance lovers, both students and professionals. They asked us to go around the room and for each person to say out loud their definition of dance. I was speechless. After decades as a dancer, no one had ever asked me this, or put me on the spot in this way. My astonishment mounted as I listened to one person after another define dance as primarily a mode of expression. The modes varied a bit—of feeling, of self, of culture, etc.—but this word “expression” was included in almost all the definitions. Now, depending on who you are and where you have experienced dance, you might take this as self-evident, or you might find this totally foreign.

A few years later, I recounted the story to my cohort in a choreography masters program in Amsterdam, and they all looked at me in bewilderment. Who in the world thinks that dance is expression? We could trace the history of this idea back to the development of modern dance, and how in the United States it was institutionalized into curricula so that this idea of dance’s essence was applied to other forms of dance, and how in Europe, when dance was formalized in institutions, neoliberalism was ascendent and the era of modern dance had already passed (because 20th century) but what I want to actually highlight here is the specific feeling when it becomes clear that your world view is not the same as anyone else in the room. In both instances I felt beside myself, as in alongside, as if the room had tilted. The feeling of hitting the edge of something.

I haven’t written what my answer was, when the curator and the marketer asked me to give a definition of dance. I said: Dance is a frame for looking at the world, because anything could be looked at as dance.

I used to believe that dance was a way of seeing. Now I would say that dance is a type of relating.

1.

S or B or T (I don’t remember) once recounted to me something like a myth or a fable, about a wise person who directed an apprentice to carry a book with them, just carry it and not open it, for months, as a way of absorbing the text. Literally just being in proximity to the physical object.

Sometimes I bring books with me to the studio and I don’t open them but they direct everything that happens.

2.

For years now I have heeded the call from A (via L) to understand dance not only as that which passes away (in time and across space) but also as that which passes around (between and across bodies of dancers, viewers, choreographers) and as that which also, always comes back around.

If it happens once, you could miss it; if it happens again, it’s a pattern. Not just a pattern that happens to occur in nature, but a pattern that you observed. A spectator is created, an object is created. There is something that moves between bodies—who can say if it’s an action or a shape or a feeling or an idea but we know when we see it, we know when it passes through us. You can imagine a dance floor, you can imagine a move that catches or spreads. You can imagine someone teaching a series of steps to someone else, who will repeat them onstage, who will teach them to someone else later on. But you can also imagine a phrase that echoes in your head years later, a small event that repeats itself, uncannily, or the feeling that you’ve been here before. A different kind of noticing flips on and that’s dance.

3.

The body is never absent from writing. (This is the original lesson from J.) You feel the tips of your fingers on the keyboard, the pressure against your ears, the shape of the room, whether the window is open or not.

Writing is never just one thing. This is where dancers can get tripped up, I believe, in thinking that it is—that words only ever pin down. But words can also slice an opening. Words can tilt the ground and then things really start rolling. With dance, with language, with dance language, the form can be episodic and ephemeral. Some ideas refuse paragraphs and the meaning can happen in between things. You can never capture embodied experience in language, but that is exactly what lights me up.

4.

Dance is the sluttiest artform and its words are too. This is part of the disciplinary baggage because sex work has long been bound up in the economics of the art form, not to say the entire scopophilic regime. But what I like is that the words are sliding, tongue over teeth, dirty callused feet on sticky floor. The words are there so you can do it again. Once a move becomes repeatable, you can give it a name. Once you find a name for something, it becomes a discrete object.

5.

There’s another angle that goes like: Dance can be anything! Dance is whatever you think it is! The definition becomes so loose it ceases to mean much. It sounds like an apologism and an offering at the same time. So few people care about dance, the lowly art form, so why not just take whatever you want from it?

V says in the meeting: To assert that everything is dance—that is a white frame.

Let’s go into this. This idea that everything is dance comes primarily out of postmodern dance in the United States, which famously worked with pedestrian and everyday movement as dance, a practice which itself had roots in modernist ideas like M’s readymades and F’s naturalized movement. This idea has been historicized as a democratization of dance, so that more and different types of bodies and expressions could appear within the form, to make it less out of reach of the “everyday” person. Then these practices became even more rarefied, inscribed in institutions and legible only to an elite class of those in the know. Power is reified once again and so arguing for the expansion of dance has an elitist ring to it, despite the democratic rhetoric. Why now expand to include “anything, any movement” in a lazy white mode, when whole lineages and legacies are still systematically excluded? Which bodies and which moves may become part of “expanded choreography” and which are still pushed off to the side?

Meanwhile, mass entertainment doubled down on virtuosity and spectacle and make-believe (xo, Y). Dance is also part of this machine of extraction. The freshest moves, scooped up and repeated, sexed up or decontextualized or commodified or artwashed, chopped up beyond recognition or definitely still recognizable but not credited. This process is as egregious and structural as centuries of imperial history, but it can also be as unconscious and social as your friend making a move on the dance floor and you doing it back. Often these modes are conflated.

I think as a field we are learning to look more critically at influences and categories, particularly when discussing specific artists and works—to point out when “expanding the category” just means stealing. How does it apply to the idea of the field, the notion of dance itself? How can “expanding the category” create actual possibility? When is expanding the category a claim to own, to traffic in, to profit from? When is it a step towards expansion of knowledge, free from these binding systems, the possibility to think otherwise?

Can we conceive of a dance that is malleable and mercurial, a trickster, not a cannibal? A shapeshifter, not a looter or a land grabber?

As I understand it, my lineage asks me to question and to take apart. My responsibility is to undo the structures of power and the ideological divisions that my ancestors created. Critique is a strategy handed down to me; it’s not enough but it can be a way in. The assignment is not to abandon, but to stay in the mess and work through it. This could look like using the English language to shift its own operations of power, to shake the grammatical structure of subject and object. Sometimes it means I literally have to take the theater apart—this architecture that was built for the sight lines of the king, this machine of consumption.

What does it look like to dismantle? Does it look like things broken down into parts? Does it look like using them to build something else? Does anything ever get discarded? How do we know we’re done breaking it down? What happens next?

6.

A texts me: i mean i famously am someone who loves the binary bc it’s something we can have a relationship with

Tell me how you relate to a container and I’ll tell you how you relate to power. Some people want to smash the walls down, some people want to reinforce them, some people want to build bridges. Some people want to pretend the power structure doesn’t exist. Are you inter- or are you anti-? Are you keeping the conversation going or are you pushing against? Are you reifying (shudder)? Do you see yourself as the person who rises above it all? Do you see yourself as trapped? Do you want to be the detonator?

The edges of a concept tell us something about how we think. If you spend time there, you will notice where different people draw the boundary, who is placed in or outside. There are different ideas about what is going too far. When does it become theater, when does it become conceptual art, when does it become poetry? What looks like something new and what looks like somewhere we’ve been before? Or when are you told, implicitly or explicitly, that you are not it? When do you intuit that something is not for you? Are you claiming the outside and turning your back on the center? Are you being placed there unwittingly, or are you the one placing something or someone on the outside?

If you expand the container, it’s still a container. If you leave the house, the house is still standing. I’m pushing on the walls from inside, filling it up with air until the structure expands and maybe the roof lifts off. I’m not trying to blow it up but I am trying to let some light in. Maybe a chain of bodies can scale the wall. Maybe it’s a trojan horse or a magic trick that fails or maybe it’s a different solution.

7.

I joke to myself that I am a Disciplinary artist. I have agreed with Dance that I am completely at its mercy. Throw me around, make me work for it, use me up. I am asking for this.

8.

In the dance studio I grew up in, as I started to enter adolescence and thereafter, I would often imagine myself being watched. Sometimes it was a fantasy of a specific crush suddenly appearing at the door, and sometimes a general sense of observation hovering in the air. I would use this to motivate myself, to bring an edge to my expression. It lent a sexual charge to the everyday work; I wanted them all to see how I could push my body.

These days the observer is always in the room via the camera phone. We know this genre of video: a wide angle captures a dancer in soft clothes, alone in a studio, dancing at nothing, dancing for what?

I think it’s strange that in performance, conventionally the audience doesn’t arrive until relatively late in the process of creating a work. The outside eyes are fundamental to the form; how could we work without them?

I have a clear memory of the first time I spent time in a dance studio completely alone. It took me the entire hour only to acclimate to the empty room, or rather, my body alone in the room.

1.

Rather than change my shape, I changed the shape of what I thought dance was, so that dance could hold me.

2.

Recently I have been practicing in the studio something I call non-objectness. I disinvite the Instagram eye, I disregard the architecture of the theater, I try not to make any “moves” or “gestures” or “material” or “states” or “dance”. There is texture and sensation but I get lost in it. I don’t strive for effort, but I also try to avoid the familiarly somatic state of non-effort. I am not trying to be authentic, I am trying to no longer recognize myself. I resent my skeleton because its shape leads to patterns that hold me up. I try to be one piece only, a singularity. Doing this with my body lets me think of something else, lets me think otherwise.

Dance can be “moves” but I refuse to believe that’s what it “is”.

3.

When A writes about desire, she has to write about the alphabet. At the origin of written language, consonants became edges and words became separated from each other, creating an electric gap. I feel this in knowledge and I feel this between bodies. I also know this in dance composition, the sharpness of separating one thing from another so that you can place it next to something else, the heat generated between them. What is discrete keeps changing. The edges of the bodies, flickering, hard. Nerves alive.

4.

Discipline can point to another context, another set of protocols. In kink, boundaries and limits are explicitly necessary to approach expansiveness. Form has the power to undo me and I let it. Dive in, splay open, get sloshed around. I am an infinite crevasse. I get lost and I find my voice.

It has something to do with becoming an object. I desire it, sometimes I ask for it, and sometimes it happens against my will. Becoming an object can be a way to move towards coherence. The move coheres enough that you can repeat it or name it; I cohere when you tell me to open my mouth. There is a sharpness and a clarity. The edges get lit up.

Objectification is a condition of viewing and a condition of my body in the world. But in the presence of technique, in the presence of consent, you can move in and out of this state, and choreograph how it happens. This passage in and out of coherence feels like dance. I can find that kind of smooth brain either with ass in the air or under the lights, and it’s the feeling of oblivion that I am always chasing. Of course the boundaries of a person, an autonomous body, are not the same as the boundaries of an idea—but the comparison I do wish to draw is that hot shit happens at the periphery.

A strong container can create a very real sense of freedom. I know this deeply in my body. What is important is that you have the agency to negotiate the shape of it, to create the container together.

Perhaps we can think about discipline in this way: not only something that you choose for yourself, but something that you negotiate with your colleagues. The container is actually very discursive and historical: it’s specific to the participants but takes into account everything our bodies have gone through, what wants to be tender and what wants to be pushed. Instead of sweeping it aside, consider how it acts on and through you, what kind of form you want to be inside, what needs to change and when. How explicit can you be about the exchange you want to have? What will actually create the conditions for freedom, and not the image of it, but the actual possibility to act?

5.

B is hiding behind the curtain. The viewers are seated in a single row of chairs across the midline of the studio. We wait. There is a standing fan and a potted tree in the corner. Street noise comes through the open window. No one moves but the fan turns on and begins to blow the leaves of the tree. Hear the air moving faster in the stillness of the studio. Watch the leaves flutter.

H says in the talkback: You’ve vacated the cliché—this is now about the periphery.

6.

Months later, the word “periphery” comes back around in conversation with V and R, as we try once again to find the right words for the work we want to be close to. So many descriptors have been announced, and then claimed, and then they circulate, and then you don’t like what sticks to them, or they just get worn out. Like how “experimental” became an aesthetic more than a method, and “contemporary” is so widely used it means next to nothing. I don’t know yet if this word will gain traction, but I do know that language pushes on us and we will push back.

7.

A word is a container, an idea is a container, discipline is a container. The theater is a container, with infinite surfaces to press against, whether marley or soft goods or assumptions. The architecture of the theater makes itself invisible; it brings its own score into the background in order to foreground what is happening. I bring language into dance because it lights up the edges, because it takes me apart so I can be remade. It pushes, it breaks the pattern, it makes people look up and pay attention.

These are the questions I would like to gather around. What is a body? How does it feel? What is time? What is it to be together? How do we move? What does it mean? What does it matter? What happens in the space between us? What will we choose to repeat? What will be different the next time it comes back around?

8.

You are dancing. [You decide what this means.] You are getting closer and closer to the edge of the room. You sense it coming and then you hit the wall. Deep thud, the sting of the impact on your skin. It flickers. You hold yourself there, you start to release, you slide down. Sweat trails like a soft snail body escaping its hard shell. The light reflects off of your effort and you can now see the texture of the surface. Your cells remain on the exterior and there is an imprint on your skin. You can see what is holding you. It is not the same anymore.